AMR causes 1.27 million deaths a year directly, and another 3.68 million people had a resistant infection when they died.

Health and Technology Strategy (HTS)

Joaquim Cardoso MSc. (Chief Editor)

January 25, 2022

The Executive Summary below was edited by the author of this blog as a christian voluntary service. On this Executive Summary Article we focus on the public health recommendations.

For the full version of the article, please refer to the original publication on the 2nd part of this post, with visual editing only.

Executive Summary (focused on the recommendations)

We need systemic change to tackle AMR

Many factors have contributed to the problem of AMR and could make it even worse in the future. One key failure is that very little money goes into researching new antibiotics, and there are few new antibiotic drugs in the pipeline.

The burden of disease helps us understand the scale of the problem, but that is only the first step.

We urgently need real progress to tackle AMR.

This will only happen when policymakers implement effective policy solutions that achieve systematic change in

- drug procurement,

- diagnostics,

- infection control, and

- other areas.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

Drug-Resistant Infections Are One of the World’s Biggest Killers, Especially for Children in Poorer Countries. We Need to Act Now.

Center for Global Development

Anthony McDonnell and Katherine Klemperer

JANUARY 20, 2022

A study out today in the lancet shows that people in low- and middle-income countries are 1.5 times more likely to die from antimicrobial resistance (AMR) than those in high-income countries.

This disparity is far greater still when you look at deaths amongst young children, most of whom would otherwise have gone on to live healthy lives. Among children under five who die from AMR, 99.65 percent are in low- or middle-income countries.

The low number of under-five deaths from AMR in high-income countries- just 893 a year-shows that large numbers of children need not die from AMR.

Still, 252,833 young children die in low- and middle-income countries from AMR each year, over half in their first month of life.

Among children under five who die from AMR, 99.65 percent are in low- or middle-income countries.

We have long known that the world is silently walking into another pandemic: the global rise in drug-resistant infections.

Of chief concern is AMR, where “superbugs” become resistant to the medicines used to treat infectious diseases.

The overuse of antibiotics around the world, amongst other things, is fuelling a proliferation of treatment-resistant bacteria that not only kill large numbers of people directly but could also undermine much of modern medicine, such as cancer treatments and many surgeries, where the risk of bacterial infection would become too high.

The overuse of antibiotics around the world, amongst other things, is fuelling a proliferation of treatment-resistant bacteria that not only kill large numbers of people directly but could also undermine much of modern medicine …

To date, we’ve only had the flimsiest idea of how many people die every year from AMR. (This blog focuses specifically on bacterial resistance including TB, which is a subset of wider AMR.)

We know that the much-quoted figure of at least 700,000 AMR deaths a year-an estimate generated by the UK’s 2014–16 AMR Review -is flawed(one of this blog’s authors did the calculations behind that number).

]This low estimate was primarily based on extrapolating worldwide deaths from US deaths, although we know deaths on average are going to be lower in the US, where rates of resistance are lower than the global average and healthcare is usually good.

But what, then, is the accurate figure?

Quantifying the burden of diseases is vitally important.

It helps policymakers, health funders, and others know which problems to focus on and where they can save the most lives, and to determine the value of interventions.

Quantifying the burden of AMR raises awareness and provides a benchmark to track the progression of resistance, so we know if policies are working or failing.

For these reasons, we are delighted the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation has today published a report on the global burden of AMR in The Lancet.

The results are scary.

The report found that :

- AMR causes 1.27 million deaths a year directly.

- Another 3.68 million people had a resistant infection when they died; this may have been a contributing factor in their deaths (researchers believe these people would have lived without the resistant infection).

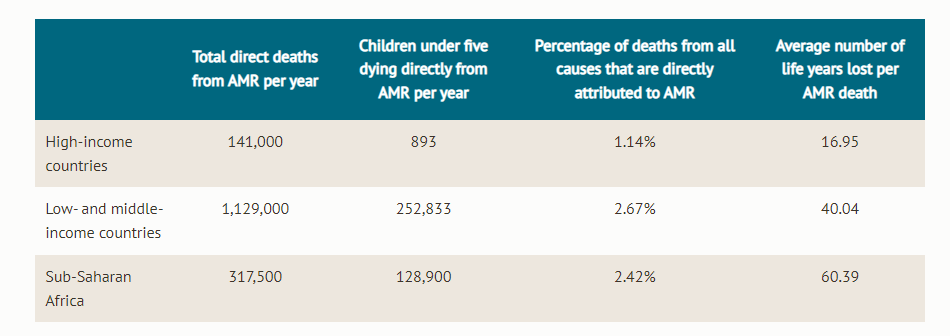

Table 1. The burden of AMR varies greatly by region

Total direct deaths from AMR per yearChildren under five dying directly from AMR per yearPercentage of deaths from all causes that are directly attributed to AMRAverage number of life years lost per AMR death

Children in sub-Saharan Africa are 58 times more likely than those in high-income countries to die of AMR

Whilst we have long known that the burden of AMR must be substantial, with studies that sampled specific areas finding very high resistance rates, this study, written by a consortium named Global Research on AntiMicrobial resistance ( GRAM), is one of the first pieces of research to systematically link all that information.

Previously, people speculated that AMR must be worst in middle-income Asian countries, where population density and antibiotic use tend to be high.

GRAM’s research suggests that the problem is worse still in low-income settings.

As mentioned, 99.65 percent of children under five who die from AMR are in low- or middle-income countries.

This high child mortality rate is the primary reason why the years of life lost per AMR death is far higher in sub-Saharan Africa than elsewhere: an average of 60 years are lost for every AMR death in sub-Saharan Africa, compared to an average of 40 across low- and middle-income countries and 17 across high-income countries.

The fact that we allow so many children born in certain parts of the world to be cut down in their first weeks of life, mostly for want of a cheap antibiotic, is shameful.

Children have no say in where they are born. The fact that we allow so many children born in certain parts of the world to be cut down in their first weeks of life, mostly for want of a cheap antibiotic, is shameful.

Globally, AMR is one of the leading causes of deaths today

To put the 1.27 million death figures into context: AMR kills significantly more people each year than HIV/AIDS, and roughly twice as many as malaria.

In fact, causing 1.27 million deaths a year makes AMR the 13 thmost common cause of death in 2019, comparable to the number of deaths from traffic accidents or tuberculosis.

To put the 1.27 million death figures into context: AMR kills significantly more people each year than HIV/AIDS, and roughly twice as many as malaria.

The number of people who die each year where AMR is a contributing factor (4.95 million) is almost as large as the official death toll from COVID-19, which stands at 5.5 million over two years and tends to count contributory cases.

However, official numbers probably greatly underestimate COVID deaths.

The Economist estimates that 19.5 million people have died with COVID as of mid-January 2022-or about twice the number of people who have died with AMR in this period.

While we expect the number of people dying from COVID-19 to drastically decrease as vaccines and improved treatments take hold, there is no indication that the numbers dying from AMR will decrease without a serious coordinated effort, which is so far lacking.

Particularly striking from the new figures is the disproportionate burden on children-254,000 children under five die from AMR each year. This equates to one child dying of AMR nearly every two minutes.

In India alone, 56,524 children each year are thought to die in their first month from antibiotic-resistant infections.

We must not allow this to continue.

Going forward, we need systemic change to tackle AMR

Many factors have contributed to the problem of AMR and could make it even worse in the future.

- One key failure is that very little money goes into researching new antibiotics, and there are few new antibiotic drugs in the pipeline.

There has not been international agreement on new ways to fund antibiotic research and development (R&D), including a fundamental change in how we purchase antibiotics, secure access to new products, and reduce unnecessary use, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

In May of this year, CGD will convene a working group on AMR seeking to improve antibiotic access and R&D in low- and middle-income countries and reduce unnecessary use. The final report will be launched in September 2023.

The burden of disease helps us understand the scale of the problem, but that is only the first step.

We urgently need real progress to tackle AMR.

This will only happen when policymakers implement effective policy solutions that achieve systematic change in

- drug procurement,

- diagnostics,

- infection control, and

- other areas.

Some 1.27 million deaths a year from AMR is already far too many. Letting that number rise even further would be unconscionable.

Originally published at https://www.cgdev.org.