Debra Weiner interviewed people who are working to beat the coronavirus about the most valuable things their parents taught them. Following are excerpts from a few of those stories, edited and condensed.

New York Times

By Debra Weiner

June 11, 2021

Various people working to stop the pandemic reflected on the life skills their parents taught them:

- determination,

- teamwork,

- resilience

- more.

Anything Is Possible

Albert Bourla Chairman and chief executive officer of Pfizer

I was born in Thessaloniki, Greece. Before the Holocaust, there were 50,000 Jews there. About 95 percent were exterminated.

A lot of survivors don’t discuss what happened to them. My family did.

On Sundays, we would gather in the living room with the relatives. My sister and cousins and I would be sitting on the floor and we’d say:

“Tell us a story about that time. Tell us a story.” And my mother would.

My mother was the youngest of seven children.

She lived in hiding with her oldest sister for a year, starting in 1943.

Like Anne Frank, my mom wasn’t supposed to go out of the house.

But she was a teenager, didn’t follow all the rules, and one day when she was out, she was spotted and arrested and put in prison.

This was toward the end of the war and the Germans were no longer sending the Jews in Greece to Auschwitz. But as a prisoner, she was beaten and abused. And every day at noon, some of the prisoners would be taken to the other side of town and the next day executed.

Her sister’s husband, who was quite wealthy, had paid a ransom to the commander of the Nazi occupation in Thessaloniki.

So her sister thought my mother was secure.

Still, each day she would go to the prison to see who was going out.

And one day she saw my mom loaded into the truck.

Her sister ran to tell her husband, who contacted the commander. “I gave you all this money. What’s this?”

He said, “I have no idea what you’re talking about. Let me see.”

My mother didn’t sleep at all that night. Someone told her to be brave but she just kept crying. At dawn, she and the others were lined up against a wall in front of a firing squad when at the last moment, a BMW motorbike with two German soldiers drove up.

They handed some documents to the officer in charge and my mother and another woman were removed from the line.

As they left to go back to the prison, she could hear the machine guns slaughtering the others.

My mother told us about everything in detail with the same easiness that I share childhood memories with my kids.

She never said, “Look what the Germans did to me.” That was irrelevant.

And she never said, “Oh, when I suffered.”

She put a humorous spin on things so we didn’t feel the horror.

And most important, the stories were filled with messages of optimism: “I was in worst position once, and now I have you and your sister.

Life is miraculous. Nothing is impossible.”

That was the spirit of her. And she inspired me to be the same.

In my first year of middle school, they told us there were going to be elections for class president, vice president and secretary.

I asked my mom, “Do you think I should raise my hand?”

She said yes.

“But I’m the only Jew in the school.”

“Just do it. Go make your speech.”

And I was elected president.

My mother believed you can do anything in life.

That there’s always a way.

The way may not be clear in the beginning, but there is always a way.

I owe her a lot because of that. She is my role model.

Listen to the Other Side

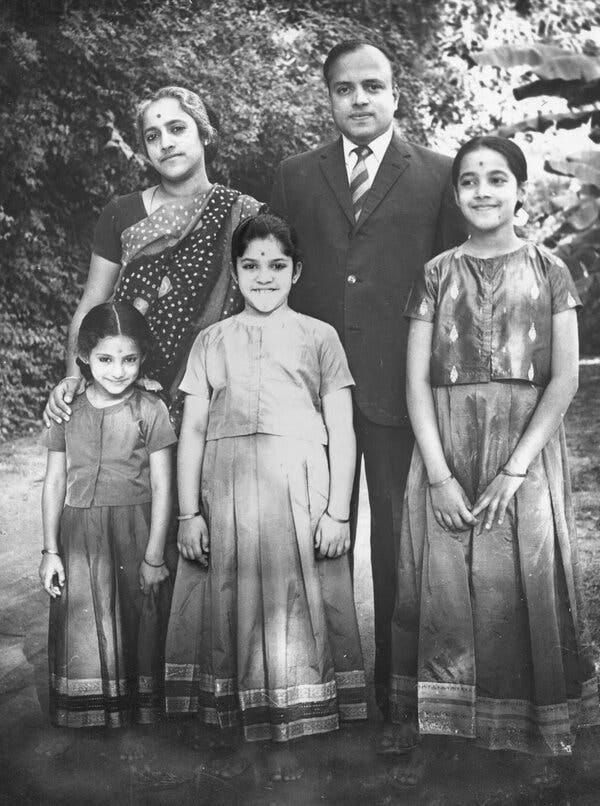

Dr. Soumya Swaminathan Chief scientist at the World Health Organization, known for her research on tuberculosis and H.I.V.

My father, MS Swaminathan, shot into prominence when he was very young. He collaborated with the Nobel Prize winner Norman Borlaug and developed new, high-yielding varieties of seeds for wheat and rice, and convinced farmers around Delhi and Punjab to grow them.

Wheat production went up three or four times.

From being a nation that had to import food grains from the United States, by the early 1970s, we were basically food secure.

My father became known as the Father of the Green Revolution.

But at the peak of his career, there was an attack on his work by some of his closest colleagues about the unintended side-effects of improving the yields of plants.

My father had himself recognized that because of the use of pesticides and fertilizers there would be some environmental damage and contamination of the water, and he had spoken about it.

But there was a euphoria at the time that India had become food self-sufficient. It was immediate benefits versus long-term risks.

The criticism was in all the newspapers. Kids at school would ask, “Is what they said true? Did your father do these bad things?” And the atmosphere at home was somber.

I remember asking my father, “Don’t you hate these people who write all these nasty things about you?”

“No, no, no. I don’t hate them,” he said. “There’s no point in being angry.

It’s their right to question and write what they want.

If you believe in something and think you are doing the right thing, then even if people criticize you, you carry on.

It can seem unfair, but there could also be some something you can take from it, some element you didn’t do right or didn’t communicate in the right way that you can try to improve on.”

My father was a problem solver and he did it by listening to the people who were most affected by the problem.

On weekends or holidays, my sisters and I, and sometimes our family’s gardener’s kids, would often go with him to the farming villages.

While we were running around in the sugar cane and wheat fields playing hide and seek, he would sit with the farmers and hear how they were doing with the new seeds and if they were having any problems, and be open to changing course if needed.

He would always say to the farmers, “This will only be a success story if it works for you.”

As a young tuberculosis researcher, I went into a remote tribal community in south India to explain why it’s very important to identify and treat people with TB early.

People in the tribe said to me: “Maybe once in two years somebody in our village gets diagnosed with TB. Our people die of other infectious diseases. Children die from diarrhea. Somebody falls in the forest, fractures their leg and we have to carry that person 15 kilometers to a health center where most often there’s no surgeon so nothing can be done.

These are our day-to-day problems, so it doesn’t seem appropriate that you’re discussing TB but aren’t trying to solve our other issues.” I thought then of my childhood and what I saw my father do.

He knew that you needed to look holistically at people’s physical, social and economic environment and see through their eyes.

When I am in a situation where I’m in disagreement or have a completely different view, I may feel at the moment quite upset.

But when I reflect further or have a discussion and try to understand where the other person is coming from, I start to say, “OK, this is why they are so negative or angry.” And that is when you start getting solutions.

Fierce Determination

Michelle Gaskill-Hames Senior vice president for hospital and health plan operations for Kaiser Permanente’s Northern California region

My parents were born and raised in the same working-class neighborhood in Detroit. They played together as kids, dated in high school, then both went to Wayne State University.

My mother majored in special education.

My father had a math and computer science degree and was selected for a management training program at Michigan Bell, which was unusual for a young African-American in the early 1960s.

Then, within less than a year of getting married, he was driving home from work and a car went through a red light and slammed into his.

His car was literally wrapped around a tree. They saved his life, but he was left paralyzed from the waist down with limited upper body movement. He was classified as a quadriplegic. He was 23. My mother was 22.

Back in that day, many quadriplegics gave up. That was never my father’s story. He wasn’t going to let the accident determine his life. He was ambitious. He had goals.

And with my mother right there with him, nothing was going to deter him from returning to work, getting a house and adopting me.

It’s funny. Some people might think having a father who was a quadriplegic is not a blessing. But to have parents who lived with such determination was the best blessing I could have ever had.

As a child, I thought it was cool that he had an electric wheelchair.

I’d ride on his lap through the neighborhood to go get ice cream.

When I got bigger, I’d ride my bike and he’d zoom along with me.

I didn’t realize that people with disabilities could be discriminated against until we were at a restaurant once when the waiter came to the table, looked at my mother and said, “What would he like to order?”

My father didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t bat an eye. He just said, “Well, I will have the prime rib, medium-rare, horseradish on the side,” and made it very clear that his disability was not in any way connected to his mind.

That was my first recognition that people might feel sorry for my father or look down on him in some way. But I never did.

And my dad never showed any sign of self-pity.

He believed there was nothing you couldn’t do if you were focused and determined.

It’s not that there weren’t obstacles, but he believed that obstacles were meant to be overcome.

When I was in sixth grade, there was an oratory contest.

Everyone had to recite a poem or speech. I thought I’d do the “I Have a Dream” speech. But my father said, “No, everybody is going to do that,” and he suggested the poem “If” by Rudyard Kipling.

It’s been my mantra ever since. I have a framed copy of it at work, right behind my desk. Whenever I’m dealing with a stressful situation, I turn around and read it. Even if I just get through the first lines:

If you can keep your head when all about you /

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you /

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you /

But make allowance for their doubting too;

I’m like, “OK. Got it. I can do this.” Not just because the words of the poem instill confidence, but because my father taught it to me. He was my hero. In my mind, he was 7 feet tall.

Resilience

Ilona Bartnik Critical care nurse, University of Chicago Medical Center

I came to Chicago from Poland in 2002. My first day in school someone gave me a list of my classes and room numbers, but I didn’t know which way to go. I didn’t know who to ask or how to ask, because I spoke then a very broken English. I was afraid people wouldn’t understand me or that I wouldn’t understand them, and then they’d make fun of me.

Especially in the beginning, I’d come home from school crying. Not because anyone had been mean, but because I was overwhelmed. My parents helped as much as they could. They’d say the typical things you tell a 17-year-old girl: “Oh, it’ll get better. You’ll make new friends.” Then they would make me my favorite meal — pierogies with strawberries or blueberries.

But I would say: “I miss my old friends. I wish we could go back to Poland. I don’t know what we’re even doing here.”

There, my mom owned a small grocery store. Everyone in our town knew us. Here, my mom was a cleaning lady. It was embarrassing.

Later my mom studied to become a dialysis technician. She would work long hours then go to school. On one hand, OK, now I don’t have to say she cleans houses. But then I never got to see her much because she was so busy.

But if it was hard for me to basically learn everything again, for my parents it was much harder. Learning a new language, getting a house in a good area, applying for a loan, even going to a grocery store, all of that was complicated. I’d hear them talking to their Polish friends who’d been here longer about which neighborhoods had good schools. Then they’d do the math to see what they could afford and get an extra job on the side just to make sure.

So they did whatever they needed to do to support us. But culture-wise, they were not as adaptable. They’d introduce me to the kids of their Polish friends, but my closest friends were other nationalities: Russian, Hispanic, Bulgarian, German. My parents were nice to them in their presence, but given Polish history there is a bit of tension between Polish and Germans, and Polish and Russians. And later it was always like, “Why don’t you just hang out with your own people” kind of thing. They didn’t understand that you can be a different color and still share the same things.

Maybe my parents preferred their own culture because it reminded them of home. Or because it felt like the one piece in their lives that they could control. But because my parents moved us here, I went from “I don’t want to change” to “I don’t want to stay the same.” I like trying new things.

This last year has been rough. Rules at the hospital changed so fast and so much. One week it was this; the next week it was that. Everyone was stressed out. But because of what I had to go through in experiencing a totally different culture, I knew I could adapt. I knew I was resilient. I knew I’d be able to cope.

Personal Connection

Dr. Anne Schuchat Principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, retiring this month

A lot of people are upset when they see bad things happening in the world. But my parents said, “What can we do about it?”

When the Russians invaded Hungary in 1956, my parents, who’d only been married three years, had two kids and were expecting a third, opened their home for several months to a Hungarian refugee family that had escaped. Later, with others from her synagogue, my mom helped set up the Anne Frank House, a residence for homeless women in Washington.

I wouldn’t say they were activists, but life was about connecting with people and our home was a gathering place.

After having five kids in seven years, my mom went back to school to get her Ph.D. in anthropology, and she would host the department parties.

This was in the ’60s, so you can imagine what her classmates were like.

Later my mom became interested in China and got involved with the U.S. China Peoples Friendship Association, and all these folks who had lived there in the 1930s or ’40s, would come to our house for meetings. And Passover Seders were an event.

We’d have almost 40 people both nights, and not just extended family. There’d be Jews and non-Jews, friends from school who’d never been to a Seder, my mom’s professors, people visiting from other countries.

Bringing people together was part of my mom’s route to happiness, and that’s maybe why I try to turn whatever community I’m with into a welcoming environment.

At the C.D.C., we have these two-year trainings for epidemic intelligence service officers. When I was branch chief, I remembered how in my mom’s office there was this fake certificate from a behavioral services organization she worked for that read, “This officially honors Molly Schuchat,” then said all these silly things. So I started making these personal little collages for the officers when they graduated.

For the person who did nose swabs on 4,000 people, the border was lots of little noses. The one who’d negotiated lots of complicated relationships between institutions got the World Peace award.

In 2014, I was asked to lead this trial of an experimental Ebola vaccine in Sierra Leone. It was in the middle of an epidemic, working with counterparts who had lost friends to this virus. At times it seemed totally hopeless and unsolvable. Everybody was exhausted, hitting walls and a little bit scared. Somebody earlier had given me pompoms, so I pulled them out and went, “OK, we can get through this; this is what we’re going to do next,” and tried to help our team see that what they were doing was really brave, and that they were making a difference.

Public health can’t just be about the results because for every problem you solve, there are 10 more you have to tackle. It’s Sisyphean work. I’ve been lucky to be part of many things that have had a positive impact on the world.

But as I moved into more senior positions, it was the warmth and connection I felt with the people I worked with that has given me joy.

As my mom once said, “It doesn’t count if you don’t share it.”

Originally published at https://www.nytimes.com on June 11, 2021.