Site editor:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Health Institute — for continuous health transformation

October 5, 2022

World Health Organization (WHO)

Departmental news

5 October 2022

A new report by the Qatar Foundation, World Innovation Summit for Health (WISH), in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) finds that at least a quarter of health and care workers surveyed reported anxiety, depression and burnout symptoms.

Our duty of care: A global call to action to protect the mental health of health and care workers — examines the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the health and care workforce and offers 10 policy actions as a framework for immediate follow-up by employers, organizations and policy-makers.

The report found that

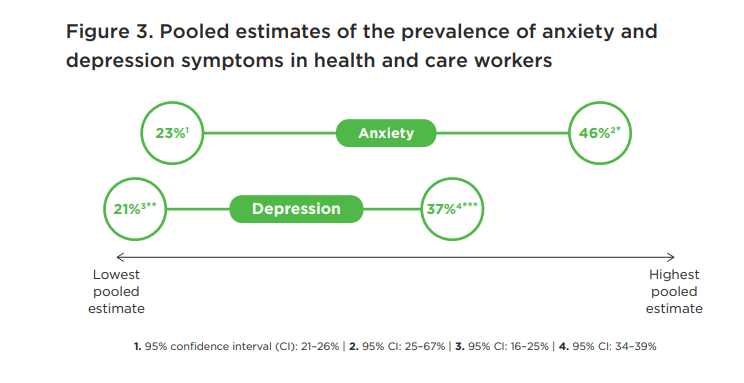

- 23 to 46 percent of health and care workers reported symptoms of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic and

- 20 to 37 percent experienced depressive symptoms.

- Burnout among health and care workers during the pandemic ranged from 41 to 52 percent in pooled estimates.

- Women, young people and parents of dependent children were found to be at greater risk of psychological distress — significant considering that women make up 67 percent of the global health workforce and are subject to inequalities in the sector, such as unequal pay.

- The higher risk of negative mental health outcomes among younger health workers is also a concern.

“Well into the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, this report confirms that the levels of anxiety, stress and depression among health and care workers has become a ‘pandemic within a pandemic,’” said Jim Campbell, WHO Director of Health Workforce.

“Well into the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, this report confirms that the levels of anxiety, stress and depression among health and care workers has become a ‘pandemic within a pandemic,’

This report follows landmark decisions at the World Health Assembly and International Labour Conference in 2022 that reaffirmed the obligations of governments and employers to protect the workforce, …

… ensure their rights and provide them with decent work in a safe and enabling practice environment that upholds their mental health and wellbeing.

Protecting and safeguarding this workforce is also an investment in the continuity of essential public health services to make progress towards universal health coverage and global health security.

“The increased pressure experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic has clearly had a detrimental impact on the health and wellbeing of health and care workers,” said Sultana Afdhal, Chief Executive Officer of WISH.

“The pressure isn’t new, but COVID-19 has brought into sharp focus the need for better care for those who care for us.

This new report sets out policy actions that promote strengthening health systems and calls for global collaboration across governments and healthcare employers to invest in safeguarding the most valuable asset that our health systems possess, which is the people working within them.”

The report highlights 10 policy actions as a framework for immediate uptake, such as investing in workplace environments and culture that prevent burnout, promote staff wellbeing, and support quality care.

This includes the obligations and roles of governments and employers for occupational safety and health.

The report highlights 10 policy actions as a framework for immediate uptake, such as investing in workplace environments and culture that prevent burnout, promote staff wellbeing, and support quality care.

This includes the obligations and roles of governments and employers for occupational safety and health.

WHO recently published recommendations for the effective interventions and approaches to support mental health at work, including those specifically for the health and care workforce, which call for organizational level changes that address working conditions and ensure confidential mental health care and support as a priority.

Relevant to this framework, the WHO Global health and care worker compact provides technical guidance on how to protect health and care workers and safeguard their rights; it highlights that duty of care is a shared responsibility in every country.

Originally published at https://www.who.int on October 5, 2022.

In addition to that, the projected shortfall of 10.2 million workers by 2030 is a grave threat to achieving UHC and to global health security.*

- The International Council of Nurses (ICN) estimated the nursing workforce shortage alone at 5.9 million globally pre-pandemic,

- and warned that a 4 percent quit rate as a result of the pandemic would increase the shortage to 7 million.7

- Further, more than 115,500 health and care workers are estimated to have died due to COVID-19 between January 2020 and May 2021,8 a figure that may even be a conservative estimate due to underreporting and limited reporting coverage.9

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION [excerpt – executive summary]

Our duty of care

A global call to action to protect the mental health of health and care workers

WISH 2022 Forum on the Mental Health of Health and Care Workers

Hanan F Abdul Rahim Meredith Fendt-Newlin Sanaa T Al-Harahsheh Jim Campbell

FOREWORD

Perhaps more than any time in recent history, the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the vital role that health and care workers play in caring for the global population.

Yet it has become increasingly clear over the last three years that we — as policymakers, employers and, ultimately, society — have largely failed in our duty of care for these essential workers, particularly with regard to their mental health and wellbeing.

Even before the pandemic, challenging working conditions, ethical dilemmas, and high-stress environments were known to increase the likelihood of mental health conditions among this group.

The unprecedented impact of COVID-19 on health services has exacerbated these issues and has also revealed stark gaps in how most health systems assess, manage and protect the mental health of their health and care workers.

This report examines the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of the health and care workforce.

It highlights effective interventions to support mental health, and provides 10 policy actions to support this group and ensure global health security now and into the future.

These actions respond to recent landmark decisions of Member States in the World Health Assembly and International Labour Conference that reaffirm the obligations of governments and employers to protect and safeguard the health and care workforce, ensuring decent work in a safe and enabling practice environment that upholds their mental health and wellbeing.

For generations the world has expected health and care personnel to deliver care to individual patients, their families and communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made clear that the obligations implicit in duty of care extend to the systems which support those personnel.

For generations the world has expected health and care personnel to deliver care to individual patients, their families and communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made clear that the obligations implicit in duty of care extend to the systems which support those personnel.

It is time for a bold commitment to protect the health and wellbeing of our health workforce.

Jim Campbell Director, Health Workforce Department, World Health Organization (WHO)

Hanan F. Abdul Rahim Dean, College of Health Sciences, Qatar University

N Sultana Afdhal Chief Executive Officer, World Innovation Summit for Health (WISH)

It is time for a bold commitment to protect the health and wellbeing of our health workforce.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Maintaining a healthy and productive health and care workforce is not only a moral imperative — it is essential to delivering safe, high-quality, patient-centered care to populations worldwide.

Yet the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that our health systems are not providing adequate support for the mental health of our health and care workers.

This is resulting in a growing workforce crisis that also threatens the delivery of care to entire populations.

Yet the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that our health systems are not providing adequate support for the mental health of our health and care workers.

This is resulting in a growing workforce crisis that also threatens the delivery of care to entire populations.

This report looks at how policymakers can address the crisis and seize the moment to redesign how health is delivered, for the benefit of all communities.

The report is presented in two main sections to examine:

1.the burden of COVID-19 on the mental health of health and care workers; and

2.interventions to support the mental health of health and care workers. The final section presents recommended policy actions.

Section 1: Burden of COVID-19 on the mental health of health and care workers

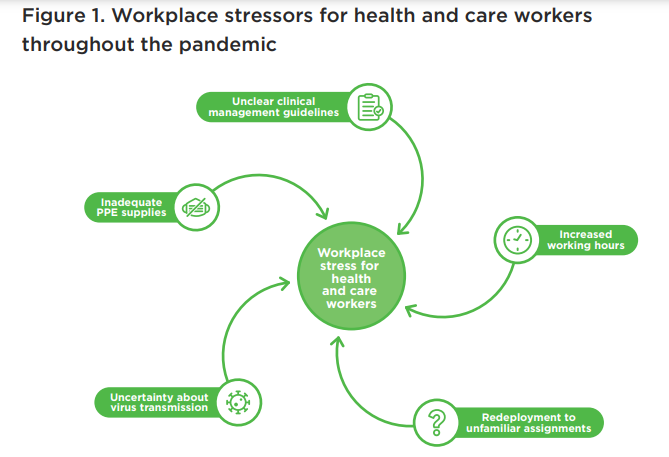

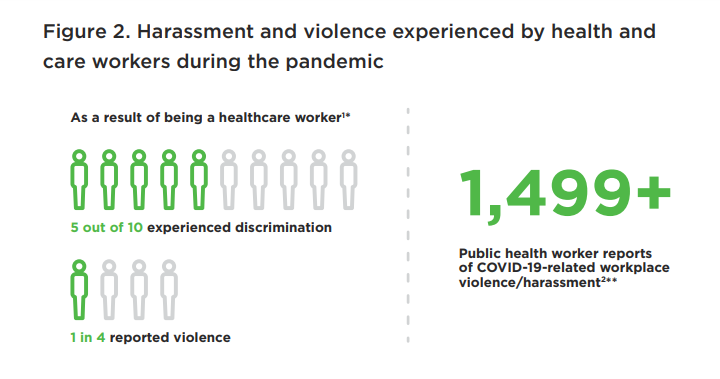

Throughout the pandemic, health and care workers experienced increased workloads, redeployment to unfamiliar settings and assignments, extreme fatigue, isolation, increased violence and harassment, stigma, and moral distress.

They have often felt abandoned and undervalued by their organizations.

All of these issues have led to increased mental health strain.

Throughout the pandemic, health and care workers experienced increased workloads, redeployment to unfamiliar settings and assignments, extreme fatigue, isolation, increased violence and harassment, stigma, and moral distress.

They have often felt abandoned and undervalued by their organizations.

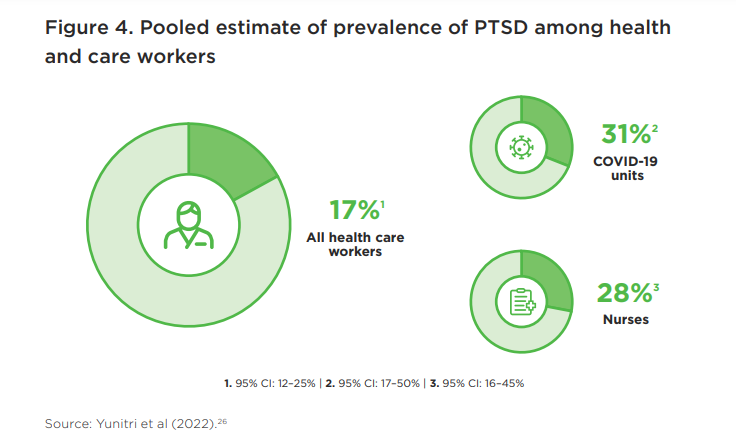

Prevalence estimates of mental health symptoms among this group during the pandemic range between 23 and 46 percent for anxiety and 20 and 37 percent for depressive symptoms according to a review of reviews between November 2021 and April 2022.

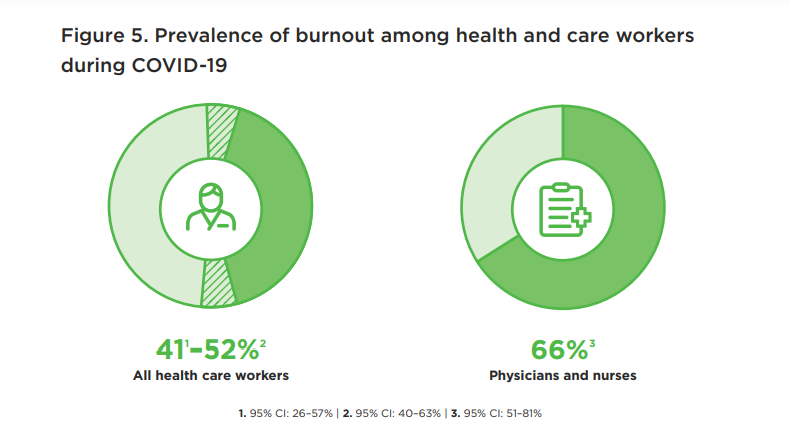

Health and care workers reported that burnout and moral distress, which affect mental health and wellbeing, and which have long plagued the health workforce, worsened because of the pandemic.

Estimates of burnout during the pandemic ranged from 41–52 percent in pooled estimates, with individual studies reporting even higher levels.

Physicians and nurses experienced the highest levels of burnout compared to other health professions.

Burnout was associated with

- increased contact with COVID-19 patients,

- lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), and

- work stress.

The rise of industrial action globally (including strikes and walkouts) impacted on the provision of essential health services.

Health and care workers voiced concerns that were not a result of the pandemic alone, but long-standing issues related to: a lack of risk allowance, insurance, overtime payment, or delayed salary; shortages in staff or equipment; and poor working conditions.

Health and care workers voiced concerns that were not a result of the pandemic alone, but long-standing issues related to: a lack of risk allowance, insurance, overtime payment, or delayed salary; shortages in staff or equipment; and poor working conditions.

As the pandemic wore on, many health and care workers either left or reported their intention to leave work, signaling the need for urgent action to protect, support and maintain the health and care workforce.

As the pandemic wore on, many health and care workers either left or reported their intention to leave work, signaling the need for urgent action to protect, support and maintain the health and care workforce.

Section 2: Interventions to support the mental health of health and care workers

Effective interventions should create enabling practice environments where the workforce’s mental health can thrive.

Doing so requires individual level interventions and psychosocial support, but also system-level prevention of risks and hazards to health and care workers’ mental health and wellbeing.

Effective interventions should create enabling practice environments where the workforce’s mental health can thrive.

Doing so requires individual level interventions and psychosocial support, but also system-level prevention of risks and hazards to health and care workers’ mental health and wellbeing.

Without this, individual psychosocial interventions will be futile, since the duration of effects are time-limited, and workers will be forced to rely on individual coping strategies or resilience training in working environments that continue to do harm.

Section 3: Policy actions

This report responds to recent landmark decisions at the World Health Assembly and International Labour Conference that have reaffirmed the obligations of governments and employers to protect the workforce, ensure their rights and provide them with decent work in a safe and enabling practice environment that upholds their mental health and wellbeing.

Protecting and safeguarding this workforce is also an investment in the continuity of essential public health services to make progress towards universal health coverage and global health security.

With clear political and technical consensus to act on the mental health and wellbeing of health and care workers, this report puts forward 10 policy-level actions across three main areas:

- the implementation of evidence-based intersectoral policies and plans;

- investment in mental health care and support; and

- strengthening human resources for health and care, including those for the mental health workforce.

These strategies are a starting point for governments and their partners to inform policy dialogue and action on addressing mental health at a time when investment in the essential health and care workforce is imperative for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

INFOGRAPHIC

INTRODUCTION

The importance of mental health for an effective health and care workforce

A thriving workforce is essential for delivering safe, high-quality, patient-centered care and achieving universal health coverage (UHC) to meet the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) by 2030.1

Evidence suggests that health and care workers who find joy, fulfilment and meaning in their work are able to engage on a deeper level with their patients.2

Poor mental health can drive professionals away from their caregiving roles, increasing the gap between the demand for and supply of workers, and leaving some people without access to health services.

Upholding health and care workers’ rights, and protecting their mental health and wellbeing, have a positive effect on ensuring that they, in turn, adequately fulfil their roles and responsibilities toward persons in their care.

A growing workforce crisis

Long considered a population at risk for increased likelihood of mental health conditions — due, in some cases, to repeated exposure to potentially traumatic events, high workload, and other challenging working conditions3 — health and care workers have recently experienced even greater strains on their mental health, adding to pre-pandemic pressure on this workforce.4 This is explored in Section 1.

“I feel like I was hung out to dry. Take chances with my health or abandon my patients were my only choices…”5 Primary care practitioner, New York, US (May, 2020)

The projected shortfall of 10.2 million workers by 2030 is a grave threat to achieving UHC and to global health security.*

- The International Council of Nurses (ICN) estimated the nursing workforce shortage alone at 5.9 million globally pre-pandemic,

- and warned that a 4 percent quit rate as a result of the pandemic would increase the shortage to 7 million.7

- Further, more than 115,500 health and care workers are estimated to have died due to COVID-19 between January 2020 and May 2021,8 a figure that may even be a conservative estimate due to underreporting and limited reporting coverage.9

The concept of ‘resilience’ in health and care workers

Resilience is often discussed in the context of individuals coping with stress, bullying and overwork.

For health and care workers, it also means coping with immense burdens during the COVID-19 pandemic.10

However, the term ‘resilience’ is overused and poorly understood.

Rather than serving to expose and challenge the conditions that create stressors and inequality, the focus on individual resilience can downplay the system’s responsibility to address the issues.

Throughout this report, the authors have made the deliberate choice to avoid describing the need for individual health and care workers to be resilient.

Instead, resilience is one of the attributes of well-functioning health systems.11

This is explored further in the WISH 2022 report Building health system resilience: A roadmap for navigating future pandemics. 12

The way forward

The world cannot afford to lose more health and care workers; meanwhile those who remain in employment face the burden of these shortages in staff workload, wellbeing, morale and the ability for staff to provide a good quality of care.

This report describes the mental health burden on health and care workers almost three years into the COVID-19 pandemic, and calls for the protection of their mental health through widescale systemic interventions and long-term action, change and investment.

In the words of the US Surgeon General, “Health workers have had our backs during the most difficult moments of the pandemic. It’s time for us to have theirs.”13

In the words of the US Surgeon General, “Health workers have had our backs during the most difficult moments of the pandemic. It’s time for us to have theirs.”

Other sections

See the original publication

SECTION 4. CONCLUSION

The costs involved in scaling up services and appropriately supporting mental health represent an investment in human resources for health that will strengthen health systems immediately, and in the future.151

The challenges for health systems, further complicated by the emergence of new, more infectious variants of COVID-19 and other public health emergencies, will persist.

Failing to tackle physical and mental health and to ensure decent work and fair pay has negative impacts that include decreased motivation, absenteeism and reduced retention.

In countries with existing workforce shortages and under-resourced health systems, this becomes even more critical.152,153

The impact of inaction is enormous and transcends health systems. Common mental health disorders are estimated to cost the global economy $1 trillion per year, largely a result of lost productivity.154

If mental health care was to be increased even to a moderate level of accessibility for health and care workers throughout the world, it would have great returns on investment by way of improved health, workforce productivity, and general economic benefits.

The impact of inaction is enormous and transcends health systems. Common mental health disorders are estimated to cost the global economy $1 trillion per year, largely a result of lost productivity.

This report promotes duty of care as a legal obligation; it is also a moral obligation which makes economic sense.

A protected, safe, healthy workforce is one that can better respond to threats, including conflicts and humanitarian emergencies in addition to future pandemics.

Increased and sustained funding is needed to develop the health and care workforces required to deliver the services that are critical to fulfilling the rights of our populations now and in the future.155

Increased and sustained funding is needed to develop the health and care workforces required to deliver the services that are critical to fulfilling the rights of our populations now and in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Forum advisory board for this paper was chaired by Mr Jim Campbell, Director of the Health Workforce Department, World Health Organization (WHO), and Dr Hanan Abdul Rahim, Dean of the College of Health Sciences, Qatar University.

The paper was written by Dr Hanan Abdul Rahim in collaboration with Mr Jim Campbell and Dr Meredith Fendt-Newlin, WHO, and Dr Sanaa T Al-Harahsheh, WISH.

Sincere thanks are extended to the members of the advisory board of the WISH 2022 Forum on the Mental Health of Health and Care Workers, who contributed their unique insights to this report:

- Mr Howard Catton, International Council of Nurses, Switzerland

- Dr Catherine Duggan, International Pharmaceutical Federation,

Netherlands - Mr Paul Farmer, Mind, UK

- Dr Cindy Frias, Institute of Neurosciences, Hospital Clinic

of Barcelona, Spain - Mrs Victoria Hornby, Mental Health Innovations, UK

- Dr Dévora Kestel, WHO, Mental Health and Substance

Use Department, Switzerland - Prof Yousef Khader, Jordan University of Science and

Technology, Jordan - Mr Iain Tulley, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

We also extend our thanks for the contributions to this report made by:

• Dr Peter Baldwin, Black Dog Institute, Australia

• Dr Matthew Coleshill, Black Dog Institute, Australia

• Dr Giorgio Cometto, WHO, Health Workforce

Department, Switzerland

• Dr Matías Irarrázaval Domínguez, Pan American Health

Organization (PAHO), Department of Noncommunicable Diseases

and Mental Health, USA

• Mr Mohamed Elgamal, Qatar University, Qatar

• Dr Jen Hall, WHO, Country Office, Fiji

• Mr Ayman Ibrahim, Qatar University, Qatar

• Ms Catherine Kane, WHO, Health Workforce

Department, Switzerland

• Dr Salma Khaled, Social and Economic Survey Research Institute,

Qatar University, Qatar

References:

See the original publication

Contents of the original publication:

- Foreword

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Section 1. Burden of COVID-19 on the mental health of health and care workers

- Section 2. Interventions to protect and support the mental health of health and care workers

- Section 3. Policy actions

- Section 4. Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- References

- Appendix: Systematic review of reviews methodology

Suggested reference for this report:

Abdul Rahim HF, Fendt-Newlin M, Al-Harahsheh ST, Campbell J. Our duty of care: A global call to action to protect the mental health of health and care workers. Doha, Qatar: World Innovation Summit for Health, 2022 ISBN: 978–1–913991–25–8