This is a republication of an excerpt of the paper “ Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019”, with the title above.

Lancet Psychiatry 2022; 9: 137–50

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators*

FEBRUARY 01, 2022

Site editor:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Health Transformation Matters (HTM)

multidisciplinary institute and content portal

October 10, 2022

SUMMARY

Background

- The mental disorders included in the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019 were depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorders, conduct disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, eating disorders, idiopathic developmental intellectual disability, and a residual category of other mental disorders.

- We aimed to measure the global, regional, and national prevalence, disability-adjusted life-years (DALYS), years lived with disability (YLDs), and years of life lost (YLLs) for mental disorders from 1990 to 2019.

Methods

- In this study, we assessed prevalence and burden estimates from GBD 2019 for 12 mental disorders, males and females, 23 age groups, 204 countries and territories, between 1990 and 2019.

- DALYs were estimated as the sum of YLDs and YLLs to premature mortality.

- We systematically reviewed PsycINFO, Embase, PubMed, and the Global Health Data Exchange to obtain data on prevalence, incidence, remission, duration, severity, and excess mortality for each mental disorder.

- These data informed a Bayesian meta-regression analysis to estimate prevalence by disorder, age, sex, year, and location.

- Prevalence was multiplied by corresponding disability weights to estimate YLDs.

- Cause-specific deaths were compiled from mortality surveillance databases.

- The Cause of Death Ensemble modelling strategy was used to estimate death rate by age, sex, year, and location.

- The death rates were multiplied by the years of life expected to be remaining at death based on a normative life expectancy to estimate YLLs.

- Deaths and YLLs could be calculated only for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, since these were the only mental disorders identified as underlying causes of death in GBD 2019.

Findings

- Between 1990 and 2019, the global number of DALYs due to mental disorders increased from 80·8 million (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 59·5–105·9) to 125·3 million (93·0–163·2), …

- …. and the proportion of global DALYs attributed to mental disorders increased from 3·1% (95% UI 2·4–3·9) to 4·9% (3·9–6·1).

- Age-standardised DALY rates remained largely consistent between 1990 (1581·2 DALYs [1170·9–2061·4] per 100000 people) and 2019 (1566·2 DALYs [1160·1–2042·8] per 100 000 people).

- YLDs contributed to most of the mental disorder burden, with 125·3 million YLDs (95% UI 93·0–163·2; 14·6% [12·2–16·8] of global YLDs) in 2019 attributable to mental disorders.

- Eating disorders accounted for 17 361·5 YLLs (95% UI 15 518·5–21 459·8). Globally, the age-standardised DALY rate for mental disorders was 1426·5 (95% UI 1056·4–1869·5) per 100000 population among males and 1703·3 (1261·5–2237·8) per 100 000 population among females.

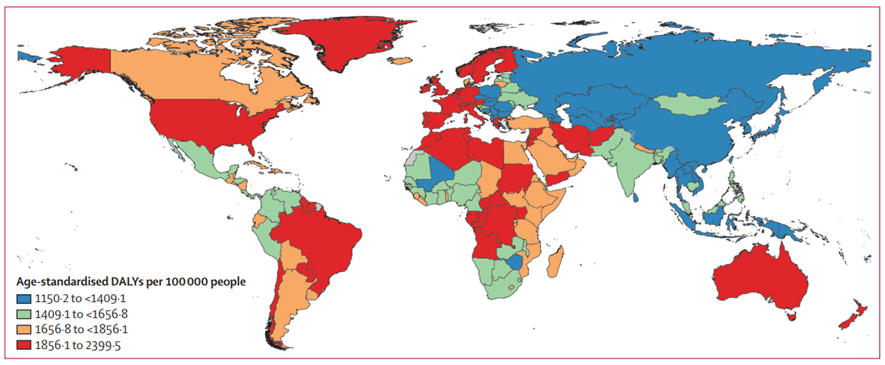

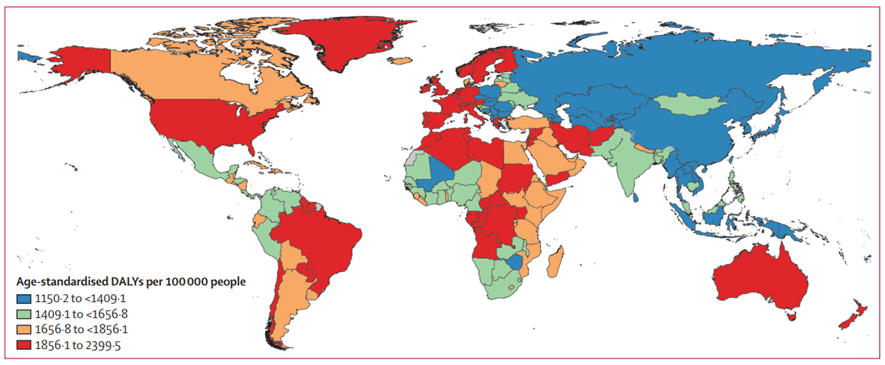

- Age-standardised DALY rates were highest in Australasia, Tropical Latin America, and high-income North America.

Interpretation

- GBD 2019 showed that mental disorders remained among the top ten leading causes of burden worldwide, with no evidence of global reduction in the burden since 1990.

- The estimated YLLs for mental disorders were extremely low and do not reflect premature mortality in individuals with mental disorders.

- Research to establish causal pathways between mental disorders and other fatal health outcomes is recommended so that this may be addressed within the GBD study.

- To reduce the burden of mental disorders, coordinated delivery of effective prevention and treatment programmes by governments and the global health community is imperative.

Funding

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, Queensland Department of Health, Australia.

To reduce the burden of mental disorders, coordinated delivery of effective prevention and treatment programmes by governments and the global health community is imperative.

Conclusion [excerpt]:

- The findings of GBD 2019 emphasise the large proportion of the global disease burden attributable to mental disorders and the global disparities in that burden.

- Furthermore, there was no evidence of global reduction in the burden since 1990, despite evidence-based interventions that can reduce the burden across age, sex, and geographical locations.

- The ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to increase the global burden of mental disorders.

- A coordinated response by governments and the global health community is urgently needed to address the present and future mental health treatment gap.

A coordinated response by governments and the global health community is urgently needed to address the present and future mental health treatment gap.

Infographic

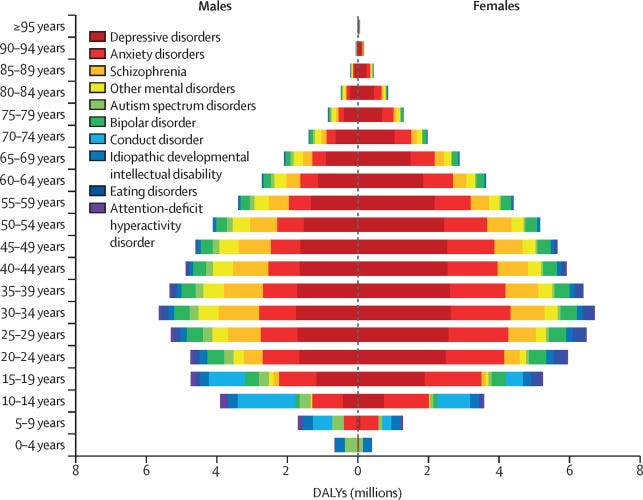

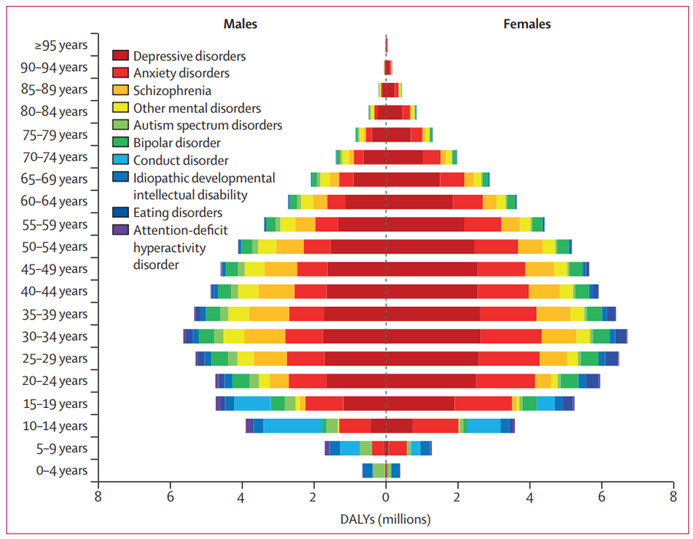

Figure 1- Global DALYs by mental disorder, sex, and age, 2019

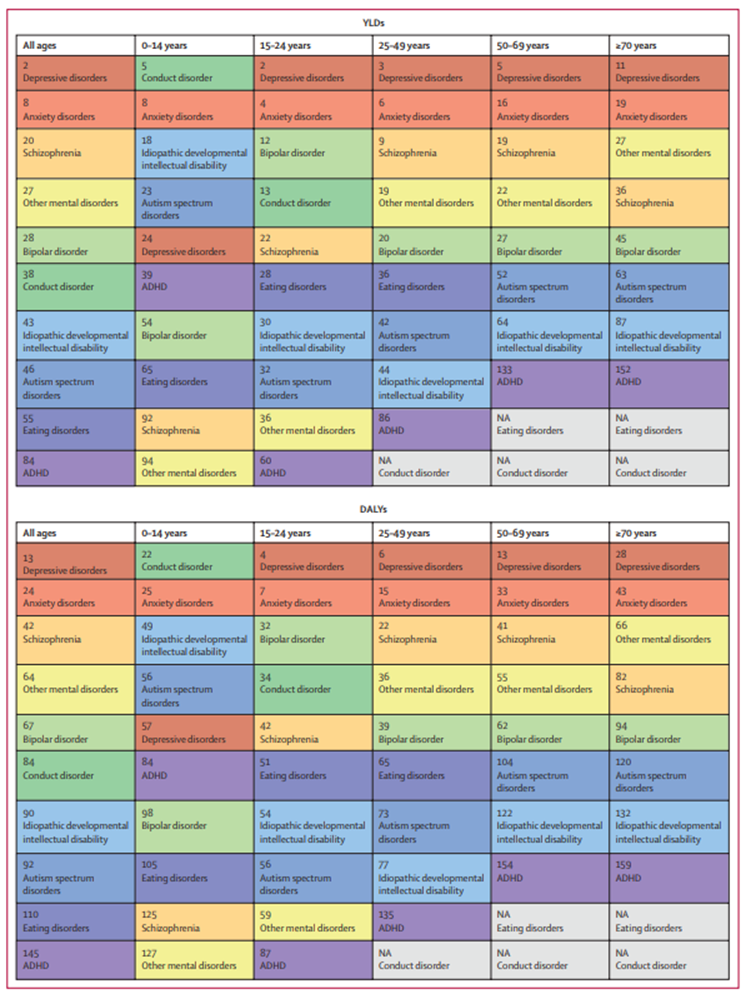

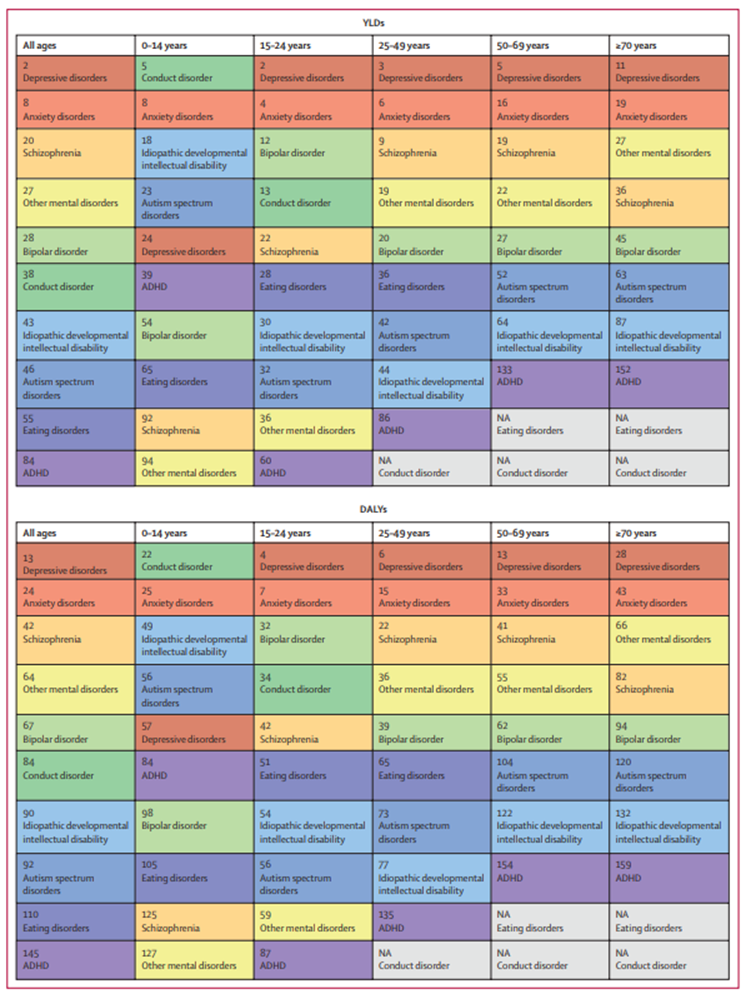

Figure 2: Rankings of YLD and DALY rates for mental disorders by all ages and five age groups for both sexes combined, 2019

Figure 3: Age-standardised DALYs per 100 000 attributable to mental disorders, 2019

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (Excerpt)

Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019

Lancet Psychiatry 2022; 9: 137–50

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators*

FEBRUARY 01, 2022

Introduction

Mental disorders are increasingly recognised as leading causes of disease burden.[1]

The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development[2] emphasised mental health as a fundamental human right and essential to the development of all countries.

The Commission called for

- more investment in mental health services as part of universal health coverage, and

- better integration of these services into the global response to other health priorities.[3]

To meet the mental health needs of individual countries in a way that prioritises transformation of health systems, in-depth understanding of the scale of the impact of these disorders is essential,[4] including their distribution in the population, the health burden imposed, and their broader health consequences.

To meet the mental health needs of individual countries in a way that prioritises transformation of health systems, in-depth understanding of the scale of the impact of these disorders is essential,[4] including their distribution in the population, the health burden imposed, and their broader health consequences.

BOX: RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Evidence before this study

The last comprehensive review of the global burden of mental disorders was published on Nov 9, 2013 using the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2010 findings, and in subsequent years there have been important updates to the burden estimation methodology and epidemiological datasets.

GBD 2019 estimated the prevalence and burden due to 12 mental disorders by age, sex, year, and location.

High-level findings of GBD 2019 were published in a capstone publication by Vos and colleagues in 2020, which covered all diseases and injuries.

We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase, and PROSPERO for papers on the global burden of mental disorders published between Oct 17, 2020 and Oct 6, 2021. We used the following search terms: (((“Mental disorders”[Title/Abstract]) AND (Global[Title/Abstract],)) AND (2019[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((“GBD 2019”[Title/Abstract]) OR (Disability[Title/Abstract])) OR (Prevalence[Title/Abstract])) OR (Burden[Title/Abstract])).

For the PROSPERO search the following additional filters were applied: Health area of review: mental health and behavioural conditions; Type and method of review: epidemiologic, systematic review, meta-analysis, and review of reviews. Our search yielded 102 studies, of which 12 were relevant to our research aim.

Of these 12 studies, two reported GBD 2019 results for eating disorders in China, and mental disorders in Mexico. We found no publications dedicated to findings of GBD 2019 mental disorders globally or for any other location by age, sex, and year.

Added value of this study

Using the most up-to-date information on the prevalence and burden of mental disorders across the global population, excluding substance use disorders and suicide, for 2019, we observed similar disparities in the burden of mental disorders as in 1990.

Mental disorders remained among the leading causes of burden globally.

Disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for mental disorders were evident across all age groups, emerging before age 5 years in individuals with idiopathic intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders, and continued to be evident at older ages in people with depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia.

We identified priority areas for improvement of the epidemiological data and burden estimation methodology for mental disorders, and provided recommendations as to how these areas might be addressed.

Implications of all the available evidence

GBD 2019 confirmed that a large proportion of the world’s disease burden is attributable to mental disorders and found no evidence of a global reduction in that burden since 1990, despite research demonstrating that interventions can achieve a reduction in the burden.

Our findings highlighted the limitations of measures for estimating years of life lost for determining the effects of mental disorders on premature mortality.

Research is needed to improve these measures to provide a more accurate picture of the true burden due to mental disorders.

GBD 2019 confirmed that a large proportion of the world’s disease burden is attributable to mental disorders and found no evidence of a global reduction in that burden since 1990, despite research demonstrating that interventions can achieve a reduction in the burden.

Our findings highlighted the limitations of measures for estimating years of life lost for determining the effects of mental disorders on premature mortality.

The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019 is a comprehensive international effort that includes the measurement of the burden of mental disorders. GBD 2019 used the disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) metric, which measures the gap between the current health of the population and a normative standard life expectancy spent in full health.

GBD 2019 built on previous iterations of the GBD study by incorporating new data and methodological improvements.

The study enabled systematic comparison of the prevalence and burden due to 369 diseases and injuries.[1] [2] [3]

Between 1990 and 2019, a reduction in DALYs from communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases has been offset by an increase in burden due to non-communicable diseases, including mental disorders.[4] [5] [6]

Between 1990 and 2019, a reduction in DALYs from communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases has been offset by an increase in burden due to non-communicable diseases, including mental disorders.

The last comprehensive review of the global burden of mental disorders was published on the basis of GBD 2010 findings, in which the combined burden of mental and substance use disorders was presented.[7]

Mental and substance use disorders are a heterogeneous group of disorders.

Health systems in many countries organise their services for these disorder groups separately, whereas in resource-poor settings, these disorders are often grouped within essential health care packages and delivery platforms.

In this study we focused on mental disorders, which allowed us to present a more detailed analysis of their distribution and burden by age, sex, location, and year than that provided by previous publications.[8] [9]

This supplements GBD 2016 findings for substance use disorders published separately.[10] There have also been significant updates to the burden estimation methodology and epidemiological datasets underpinning GBD findings since this publication.[11]

In this study, we aimed to facilitate access and interpretation of GBD 2019 estimates for stakeholders, including governments and international agencies, researchers, and clinicians involved in the identification, management, and prevention of mental disorders; present and evaluate the methods used to estimate the burden of mental disorders; and highlight priority areas for improvement in the mental disorder burden estimation methodology.

Methods and other sections

See the original publication

Discussion

In 2019, we observed similar disparities in the global distribution and burden of mental disorders as in 1990.

Depressive and anxiety disorders remained among the leading causes of burden worldwide (ranked 13th and 24th leading causes of DALYs, respectively) with prevalence estimates and disability weights comparatively higher than many other diseases.

Depressive and anxiety disorders remained among the leading causes of burden worldwide

Schizophrenia impacted a smaller proportion of the global population than depressive and anxiety disorders, but the disability weight for an acute state of psychosis was the highest estimated across the GBD study.

Schizophrenia impacted a smaller proportion of the global population than depressive and anxiety disorders, but the disability weight for an acute state of psychosis was the highest estimated across the GBD study.

The persistently high prevalence of these disorders, in addition to bipolar disorder and eating disorders, is especially concerning, because they not only impair health in their own right, but also increase the risk of other health outcomes, such as suicide (rated as the 18th leading cause of mortality in GBD 2019).[1]

The persistently high prevalence of these disorders, in addition to bipolar disorder and eating disorders, is especially concerning, because they not only impair health in their own right, but also increase the risk of other health outcomes, such as suicide

We found no marked variation in burden by sex for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

The burden of depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders was greater in females than males.

Burden of autism spectrum disorders and ADHD was greater in males than females. In 2019, 80·6% of the burden due to mental disorders occurred among individuals of working age (16–65 years).

Around 9·2% of the remaining burden occurred in people aged younger than 16 years.

In 2019, 23·2% of children and adolescents worldwide were located in sub-Saharan Africa, where mental disorders in these age groups pose considerable challenges for economies that already have limited resources dedicated to mental health at a developmental stage when the implementation of prevention and early intervention strategies for mental disorders is crucial.

Overall, DALY rates for mental disorders were high in many high-income countries and were lowest in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, …

… where the coverage of epidemiological data was lowest, and therefore there is more uncertainty surrounding estimates.

Disorder-specific trends were also identified.

For example, DALYs for depressive and anxiety disorders were high in countries with high rates of childhood sexual abuse,[2] intimate partner violence,[3] and conflict and war.[4]

For example, DALYs for depressive and anxiety disorders were high in countries with high rates of childhood sexual abuse,[2] intimate partner violence,[3] and conflict and war.[

The age-standardised DALY rates for mental disorders remained fairly constant between 1990 and 2019, but the overall number of DALYs increased by 55·1%.

This growth is expected to continue due to population growth and highlights the need for health systems, especially those in low-income and middle-income countries, to deliver the treatment and care needed for this growing population.

Effective intervention packages for mental disorders exist.

These interventions have the potential to reduce the burden due to mental disorders by decreasing the severity of symptoms, increasing remission, or reducing the risk of mortality.[5]

However, at the global level, there are substantial shortages in access to these services, and in the resources allocated for their scale-up, as well as various barriers to care such as perceived need for care and stigma surrounding mental health problems.[6] [7]

However, at the global level, there are substantial shortages in access to these services, and in the resources allocated for their scale-up, as well as various barriers to care such as perceived need for care and stigma surrounding mental health problems

In high-income countries where increases in the uptake of treatment for mental disorders have been observed since 1990, treatment is still not reaching minimally adequate standards or those in the population who need it the most.[8]

To reduce the burden of mental disorders, we need to expand the delivery of effective prevention and treatment programmes with established efficacy[9] to cover more of the population for the necessary duration.

However, at the global level, there are substantial shortages in access to these services, and in the resources allocated for their scale-up, as well as various barriers to care such as perceived need for care and stigma surrounding mental health problems

Figure 1: Global DALYs by mental disorder, sex, and age, 2019

DALYs=disability-adjusted life-years.

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has created an environment in which many determinants of poor mental health outcomes have been exacerbated.

Epidemiological research suggests that the direct psychological effects of the pandemic and the long-term impacts on the economic and social circumstances of a population might increase the prevalence of common mental disorders.[10]

Efforts to establish the dataset and methodology from which the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the burden of mental disorders can be quantified within the GBD study have been summarised elsewhere.[11]

Our findings demonstrated that mental disorders already imposed a substantial burden before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although it is important to consider the impact of COVID-19 on mental health, the existing unmet mental health needs of the population must also be considered as we focus on recovery from this pandemic.

Our GBD 2019 results serve as a stark reminder for countries to re-evaluate their mental health service response more broadly.

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has created an environment in which many determinants of poor mental health outcomes have been exacerbated.

Our findings demonstrated that mental disorders already imposed a substantial burden before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The burden estimation methodology for mental disorders used in this study had some key limitations and identified priority areas for improvement.

First, despite the considerable amount of new epidemiological data incorporated since our previous GBD 2010 publication on the burden of mental disorders,[12] some estimates continued to rely on sparse datasets, and high-quality survey data remain scarce for many countries. On the basis of burden of disease analyses done since GBD 2010, we remain concerned about the quality of epidemiological data available for mental disorders. Our systematic literature review made use of inclusion criteria imposing minimum standards to data collection methodology across studies. We recommend that these standards be considered by researchers undertaking new mental health surveys, specifically with regard to decisions around case definitions, instruments, sampling strategy, and standard of reporting.

Figure 2: Rankings of YLD and DALY rates for mental disorders by all ages and five age groups for both sexes combined, 2019

Mental disorders were ranked out of all Level 3 causes within the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study. Disorders are ordered from highest to lowest ranking for the all ages group. Each colour represents a different mental disorder. Grey cells marked NA show disorders for which burden was not estimated within the age group. ADHD=attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. DALYs=disability-adjusted life-years. YLDs=years lived with disability

Figure 3: Age-standardised DALYs per 100 000 attributable to mental disorders, 2019

DALYs=disability-adjusted life-years.

Second, it was difficult to quantify and remove all variation due to measurement error in our prevalence estimates. We corrected for known sources of bias caused by survey methods but few datapoints were available to inform such adjustments for some disorders and other important sources of variation in prevalence remain unquantified. For example, it is difficult to disentangle reasons for cross-national differences in our burden estimates. The importance of cross-culturally comparable case definitions and case-finding for mental disorders has been emphasised,[13] but the epidemiological data informing burden estimates are limited in this respect. The use of DSM and ICD classifications, which ensures consistency in case definitions across studies, might not be sensitive to all cultural contexts.[14] The cross-cultural applicability of our case definitions and data collection methodology need to be considered in future research. The uncertainty intervals reported here do not incorporate these sources of bias that are difficult to quantify, including measurement bias not captured by our bias corrections, selection bias due to missing data, and model specification bias.

Third, our estimation of severity distributions was derived from few studies, mostly from high-income countries. Imposing severity distributions from high-income countries to all locations is likely to have underestimated burden in countries with little or no access to treatment and needs to be reconsidered. Raw data on the severity distribution of mental disorders by location that would facilitate this work is not available. However, alternative work to model the impact of access to health care on the severity of mental disorders is ongoing within the GBD study.

Fourth, the majority of the epidemiological data within our datasets adhered to DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic classifications. With the emergence of more epidemiological surveys using DSM-5 and ICD-11 classifications, work to account for the impact of changes to diagnostic classifications within our GBD estimates will be undertaken.

Fifth, the mental disorders included in GBD 2019 were those with sufficient epidemiological data at a global level required for burden of disease analysis. Personality disorders were captured through the residual group of other mental disorders in GBD 2019, with limited sources available to inform their prevalence and disability weight analysis. Binge eating disorder and the group of ‘other specified feeding or eating disorders’ are likely to explain a substantial proportion of eating disorder burden currently not captured by GBD analyses.[15] Efforts to compile the required datasets and analyses for formal inclusion of these disorders in the GBD study is underway.

Sixth, our study did not consider substance use disorders or neurological disorders. An evaluation of the burden imposed by this broader group of disorders was done for the 2016 review of Disease Control Priorities.[16]

Seventh, the differential mortality gap for individuals with mental disorders needs to be reflected within the GBD framework. Within the mental disorder group, deaths were estimated for only eating disorders. These estimated deaths are extremely low, and not reflective of premature mortality in individuals with eating disorders, or with other mental disorders where the direct cause of death is another disease or injury. Alternative mortality-based metrics have shown that excess deaths in people with mental disorders occur not just from suicide and other external causes but also from infectious diseases, neoplasms, diabetes, and circulatory system and respiratory diseases.[17] [18] These deaths are assigned to those causes within the GBD 2019. A method for capturing the proportion of premature deaths from physical health causes that can be causally attributed to the mental disorder experienced by a person is not yet available for our estimation of YLLs. However, where the evidence exists, it is feasible to use comparative risk assessment to quantify the contribution of mental disorders to premature mortality. Supplementary GBD 2010 analyses found that the inclusion of attributable suicide DALYs would have increased the overall burden of mental and substance use disorders from 7·4% to 8·3% of all global DALYs, increasing their global ranking from fifth to third.[19] An update to this work using GBD 2020 estimates is in progress, and the first publication using the application of meta-regression techniques to summarise the relative-risk of mental disorders as risk factors for suicide is available.[20] Further work to establish causal pathways between mental disorders and other health outcomes is required to enable replication of this analysis for other fatal outcomes within the GBD study.

Eighth, broader limitations in the GBD study should be acknowledged. Our definition of disability reflects health loss but not welfare loss. Estimates therefore do not capture the full impact of mental disorders on society. Disability weights were derived from brief descriptions of disease states that might not capture the full complexity of symptoms, across settings. Replication of the disability weight survey across more locations, containing more lay descriptions associated with mental disorders, is required to investigate the generalisability of estimates. We assume independent distributions of comorbid conditions when adjusting YLDs for comorbidity within GBD 2019. This assumption is a limitation especially for mental disorders since comorbidity distributions might be dependent on the combination of disorders experienced. Efforts to incorporate dependent comorbidity within the GBD study have been challenging owing to scarcity of data to inform the correlation structure of prevalence consistently for all diseases and injuries. Even within mental disorders, additional research is required as information on dependent comorbidity is available for only a small subset of possible combinations of disorders and is limited to specific age groups and populations.

The findings of GBD 2019 emphasise the large proportion of the global disease burden attributable to mental disorders and the global disparities in that burden.

Furthermore, there was no evidence of global reduction in the burden since 1990, despite evidence-based interventions that can reduce the burden across age, sex, and geographical locations.

The ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to increase the global burden of mental disorders.

A coordinated response by governments and the global health community is urgently needed to address the present and future mental health treatment gap.

A coordinated response by governments and the global health community is urgently needed to address the present and future mental health treatment gap.

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators

Alize J Ferrari, Damian F Santomauro, Ana M Mantilla Herrera, Jamileh Shadid, Charlie Ashbaugh, Holly E Erskine, Fiona J Charlson, Louisa Degenhardt, James G Scott, John J McGrath, Peter Allebeck, Corina Benjet, Nicholas J K Breitborde, Traolach Brugha, Xiaochen Dai, Lalit Dandona, Rakhi Dandona, Florian Fischer, Juanita A Haagsma, Josep Maria Haro, Christian Kieling, Ann Kristin Skrindo Knudsen, G Anil Kumar, Janni Leung, Azeem Majeed, Philip B Mitchell, Modhurima Moitra, Ali H Mokdad, Mariam Molokhia, Scott B Patten, George C Patton, Michael R Phillips, Joan B Soriano, Dan J Stein, Murray B Stein, Cassandra E I Szoeke, Mohsen Naghavi, Simon I Hay, Christopher J L Murray, Theo Vos, and Harvey A Whiteford.

Brazilian co-authors & affiliations

Christian Kieling

Department of Psychiatry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil (C Kieling MD); Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil (C Kieling MD)

Affiliations

School of Public Health (A J Ferrari PhD, D F Santomauro PhD, A M Mantilla Herrera PhD, J Shadid BSc, F J Charlson PhD, H E Erskine PhD, Prof H A Whiteford PhD), Queensland Brain Institute (Prof J J McGrath MD), and Center for Youth Substance Abuse Research (J Leung PhD), University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research, Wacol, QLD, Australia (A J Ferrari PhD, D F Santomauro PhD, A M Mantilla Herrera PhD, J Shadid BSc, F J Charlson PhD, H E Erskine PhD, Prof J G Scott PhD, Prof J J McGrath MD, Prof H A Whiteford PhD); Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (A J Ferrari PhD, D F Santomauro PhD, A M Mantilla Herrera PhD, J Shadid BSc, C Ashbaugh MA, F J Charlson PhD, H E Erskine PhD, Prof L Degenhardt PhD, X Dai PhD, Prof L Dandona MD, Prof R Dandona PhD, M Moitra MPH, Prof A H Mokdad PhD, Prof M Naghavi MD, Prof S I Hay FMedSci, Prof C J L Murray DPhil, Prof T Vos PhD, Prof H A Whiteford PhD) and Department of Health Metrics Sciences, School of Medicine (X Dai PhD, Prof R Dandona PhD, Prof A H Mokdad PhD, Prof M Naghavi MD, Prof S I Hay FMedSci, Prof C J L Murray DPhil, Prof T Vos PhD), University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (Prof L Degenhardt PhD) and School of Psychiatry (Prof P B Mitchell MD), University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Mental Health Programme, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, QLD, Australia (Prof J G Scott PhD); National Centre for Register-based Research, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark (Prof J J McGrath MD); Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden (Prof P Allebeck MD); Department of Epidemiology and Psychosocial Research, Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz National Institute of Psychiatry, Mexico City, Mexico (C Benjet PhD); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health (Prof N J K Breitborde PhD) and Department of Psychology (Prof N J K Breitborde PhD), Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA; Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK (Prof T Brugha MD); Public Health Foundation of India, Gurugram, India (Prof L Dandona MD, Prof R Dandona PhD, G Kumar PhD); Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India (Prof L Dandona MD); Institute of Gerontological Health Services and Nursing Research, Ravensburg-Weingarten University of Applied Sciences, Weingarten, Germany (F Fischer PhD); Department of Public Health, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands (J A Haagsma PhD); Research Unit, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain (J M Haro MD); Biomedical Research Networking Center for Mental Health Network, Barcelona, Spain (J M Haro MD); Department of Psychiatry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil (C Kieling MD); Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil (C Kieling MD); Centre for Disease Burden, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Bergen, Norway (A S Knudsen PhD); Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Imperial College London, London, UK (Prof A Majeed MD); Faculty of Life Sciences and Medicine, King’s College London, London, UK (M Molokhia PhD); Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada (Prof S B Patten PhD); Department of Pediatrics (Prof G C Patton MD), Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry, and Health Sciences (Prof C E I Szoeke PhD), University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Population Health Theme, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia (Prof G C Patton MD); Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China (Prof M R Phillips MD); Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA (Prof M R Phillips MD); Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Autonomous University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain (Prof J B Soriano MD); Center for Biomedical Research in Respiratory Diseases Network, Madrid, Spain (Prof J B Soriano MD); Risk and Resilience in Mental Disorders Unit, South African Medical Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa (Prof D J Stein MD); Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA (M B Stein MD); The Brain Institute, Australian Healthy Ageing Organisation, Melbourne, VIC, Australia (Prof C E I Szoeke PhD).

References

See the original publication