The administration has made clear progress toward several of the international objectives identified in its January 2021 strategy.

Nevertheless, far greater US investment and leadership will be required to get control of COVID-19 in the United States and around the world.

Center for Global Development

Eleni Smitham, Amanda Glassman, Jocilyn Estes and Erin Collinson

JANUARY 21, 2022

The Executive Summary below was edited by the author of the blog, as a christian voluntary service, with the purpose to reach out for the Brazilian audience. The purpose here is to help fight the pandemic.

For the full version of the original publication, please, refer to the 2nd part of this post.

Health and Digital Strategy

Joaquim Cardoso MSc. (Chief editor of the blog)

January 26, 2022

Executive Summary

Today marks one year since President Biden unveiled a National Strategy for the COVID-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness. Its overarching goal is to “guide America out of the worst public health crisis in a century.”

Sadly, amid our collective inability to limit transmission, cases are again increasing around the world.

Omicron has been a tragic reminder that bringing the pandemic under control will require a more ambitious approach to slowing the spread of COVID-19 beyond US borders. Unchecked transmission anywhere in the world provides the virus with more opportunities to replicate, leaving the possibility that new variants emerge.

So even as the fight to control COVID-19 at home is far from over, to bring an end to the pandemic, the administration must dramatically expand its global response work-and continue its efforts to rally the international community.

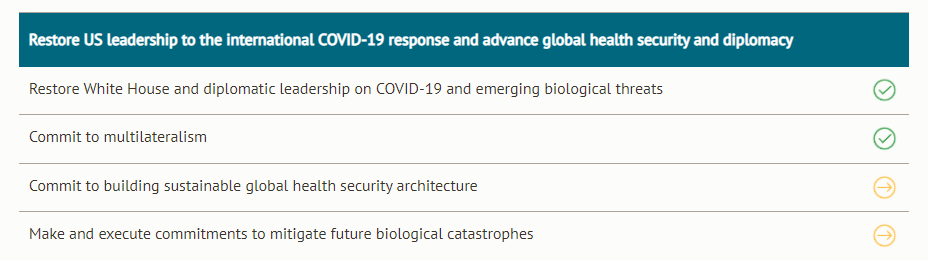

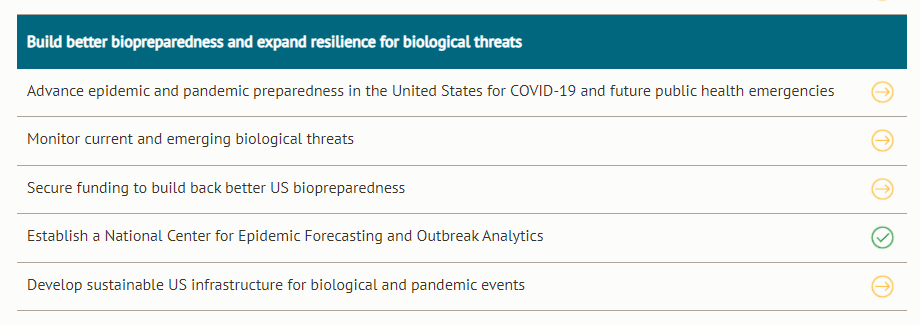

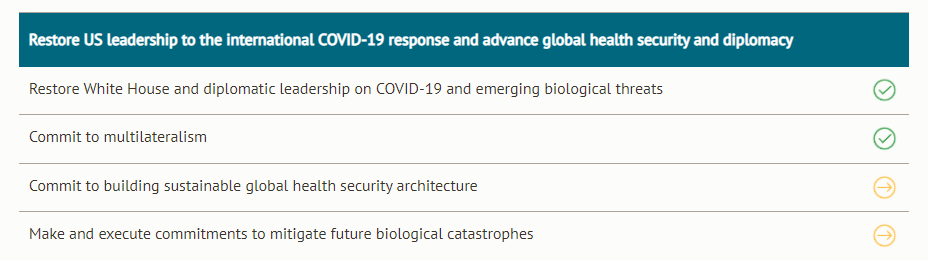

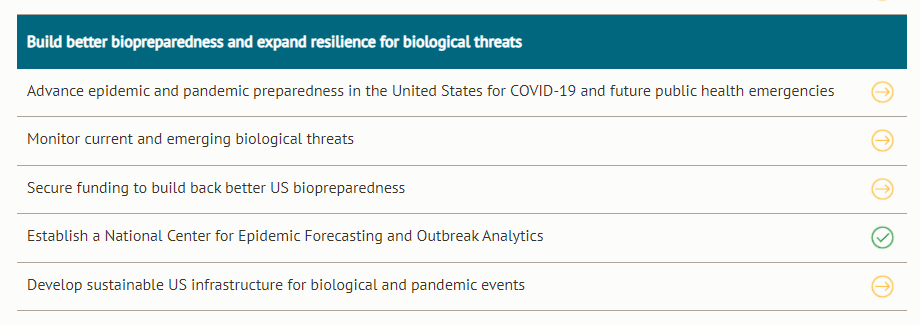

Table 1. Overview of Progress on Goal Seven: Restore US leadership globally and build better preparedness for future threats

Build better biopreparedness and expand resilience for biological threats

The administration unveiled a new plan called the “American Pandemic Preparedness: Transforming Our Capabilities” — expected to cost $65.3 billion — -to invest heavily in US biodefense, which would include vaccine, therapeutic, and diagnostic capabilities, early threat detection and forecasting, strengthening public health systems, and establishing strong mission management of these efforts.

This plan, and the administration- ordered whole-of-government review and update of US national biopreparedness policies was meant to culminate in the release of a strategy on biodefense and pandemic readiness, but we’re still waiting on its release.

More is needed

A year later, the administration has made clear progress toward several of the international objectives identified in its January 2021 strategy. It deserves credit for what it has accomplished, but sadly the pandemic’s advance has far outpaced international efforts to contain it.

The good news is that we have more tools and information than we did in the early days of the pandemic.

Nevertheless, far greater US investment and leadership will be required to get control of COVID-19 in the United States and around the world.

In parallel, the US must continue to push for improvements in global health security, including the creation of a financing mechanism to incentivize countries to enhance preparedness and perhaps even a bold new initiative, that will leave the United States and the world better prepared to face future health threats.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (long version)

Today marks one year since President Biden unveiled a National Strategy for the COVID-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness. Its overarching goal is to “guide America out of the worst public health crisis in a century.”

Sadly, amid our collective inability to limit transmission, cases are again increasing around the world.

New global daily cases yesterday totaled over three and a half million, nearly 650,000 of which were in the United States.

This first anniversary presents an opportunity to reflect on where the US has made progress in combating the pandemic and identify what’s still needed-taking into account the ongoing risk of emergent variants.

Much of the administration’s strategy focused on the US domestic response to COVID-19-but in this blog we concentrate our attention on the seventh, and final, goal: “Restore US leadership globally and build better preparedness for future threats.”

Unchecked transmission anywhere in the world provides the virus with more opportunities to replicate, leaving the possibility that new variants emerge that pose a greater threat to human populations-including those in the US.

Omicron has been a tragic reminder that bringing the pandemic under control will require a more ambitious approach to slowing the spread of COVID-19 beyond US borders.

Unchecked transmission anywhere in the world provides the virus with more opportunities to replicate, leaving the possibility that new variants emerge.

So even as the fight to control COVID-19 at home is far from over, to bring an end to the pandemic, the administration must dramatically expand its global response work-and continue its efforts to rally the international community.

Here we provide a rundown of the administration’s progress toward achieving goal seven and offer suggestions for advancing the fight against COVID-19 and readiness to combat future global health threats.

Table 1. Overview of Progress on Goal Seven: Restore US leadership globally and build better preparedness for future threats

Restore the US relationship with the World Health Organization and seek to strengthen it

In January 2021, President Biden sent a letter to UN Secretary-General António Guterres, indicating the US would rejoin-or, more accurately, reverse course on a potentially disastrous planned withdrawal from-the World Health Organization (WHO). However, efforts at substantive organizational reform have largely stalled.

Assessed contributions (annual dues members pay to the WHO, calculated based on the country’s wealth and population) provide stable, predictable funding for the WHO, but at about $1 billion account for less than 20 percent of WHO’s total income-and have remained relatively static. US assessed contributions to the WHO remained constant over almost a decade between FY 2010 and FY 2019. At a December meeting of the WHO Working Group on Sustainable Financing, held in Geneva, the US declined to support a proposal to increase assessed contributions, amid clear arguments that the organization needs additional resources to ensure sufficient independence and the scale of its operations.

Moving forward, the US will need to put in the diplomatic elbow grease required to adequately finance, reform, and strengthen the WHO. When it comes to technical advice and standards, the WHO must be at the center of coordinating ongoing efforts to prevent future pandemics. Further, the WHO is an essential complement to other needed investments in global health and pandemic preparedness. The White House should prioritize cooperation with allies and other global health actors to address major challenges that persist in the organization-including clearly delineating the WHO’s role in the international global health architecture and increasing assessment-based contributions from member states.

Moving forward, the US will need to put in the diplomatic elbow grease required to adequately finance, reform, and strengthen the WHO.

Surge the international COVID-19 public health and humanitarian response

Two years into the pandemic, the US remains the largest donor across multiple dimensions of the global response. The US has donated more vaccine doses than any other country and-with appropriated funding that pre-dated President Biden’s inauguration-pledged the largest contribution to the multilateral vaccine platform COVAX. The current administration provided crucial early support to COVAX’s Advance Market Commitment via Gavi, promising $2 billion for vaccine procurement for lower-income countries, and secured a $3.5 billion contribution to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (through the American Rescue Plan (ARP)) out of $11 billion in funding to support the international COVID-19 response. US funding accounted for one-third of country commitments to the ACT Accelerator partnership for 2020–21 ($18.8 billion)-which, in addition to vaccines, aims to mobilize funding for diagnostics, therapeutics, PPE, and related health tools-more than double the next largest bilateral contributor.

The administration identified enhanced humanitarian relief and support capacity for response in the “most vulnerable communities” as a priority for US response efforts. An aim buoyed by resources included in the ARP-$3 billion for the USAID’s chief humanitarian account and $500 million in supplemental assistance to support migrant and refugee communities. The US also brokered a deal to facilitate delivery of single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccines to people in conflict zones and other humanitarian settings. And the White House encourag ed vaccine manufacturers to waive indemnification requirements for COVAX’s Humanitarian Buffer-a 5 percent set aside of the vaccines it procures, reserved for humanitarian contexts to address potential equity gaps.

Frustratingly, it’s difficult to get a full impression of the US global response to COVID-19 or glean a complete understanding of where emergency funds have been spent and how much remains. USAID releases semi-regular fact sheets on its COVID-19 response, while the State Department publishes topline totals for vaccine donations on a timely (if limited in terms of detail) basis. Periodic press releases tout highlights and topline commitments. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) planned to spend $800 million in 2020, but their page on their COVID-19 global response hasn’t been updated since August 5, 2020 (accessed 12:00pm on 1/20/2022), a pity because the goals and objectives of the CDC’s response program were clearly delineated. Officials from the State Department and USAID, who testified before a House Appropriations panel in October, underscored that resources for global pandemic response had largely been committed by that point-and were likely to be fully exhausted by early 2022. Even as the supply of COVID-19 vaccine doses grows, other resources necessary for immunization delivery are dwindling. This change will limit the United States’ ability to support the logistically challenging but critical work of getting shots in arms.

Amid recent reports that the White House is preparing a supplemental request to Congress for funding to address COVID-19 and that lawmakers are evaluating new or renewed forms of COVID-19 relief, the global response needed to end the pandemic should be central to the discussion. It’s also vital that, as the administration scales up the ambition of its international response, it commits to regular, detailed updates on its pandemic spending.

In July 2021, the administration released a 12-page US COVID-19 Global Response and Recovery Framework, a critical step toward operationalizing the national strategy. In the future, the administration should look to craft an international response framework to guide the US response to a broader range of potential future global health threats.

Restore US leadership to the international COVID-19 response and advance global health security and diplomacy

Upon taking office last January, President Biden quickly reinstated the National Security Council Directorate on Global Health Security and Biodefense. And over the last year, a number of individuals, offices, agencies across the administration have been tapped to lead elements of the pandemic response. If anything, the criticisms leveled at the administration on the subject of personnel have suggested perhaps there are too many cooks in the kitchen or at least that disentangling the different roles to identify the individual most responsible is a persistent challenge.

President Biden hosted a Global COVID-19 Summit in September, seeking to mobilize increased resources from the international community and private sector. But while the US unveiled several new commitments, other donors showcased less ambition.

The administration has found allies in mobilizing investment to advance vaccine manufacturing around the world. The US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) expanded its health-focused portfolio under a nascent Health and Prosperity Initiative, pursuing a $383 million project to back the purchase of COVID-19 vaccines by Gavi for distribution to lower-income countries and a joint financing package (with support from IFC, Proparco, and DEG) to support production of vaccines, and other therapies in emerging markets.

In contrast to his predecessor, President Biden also made an early point of courting multilateral cooperation by calling on G7 partners to prioritize a “sustainable health security financing mechanism aimed at catalyzing countries to build the needed capacity to end this pandemic and prevent the next one.” In a welcome commitment at the Global COVID-19 Summit last year, Vice President Harris announced the US intention to contribute at least $250 million to help seed a new global health security financial intermediary fund. But despite concrete proposals by the G20 High-Level Independent Panel on Financing the Global Commons for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, and others to bring such a financing mechanism to fruition, this is still a work in progress, to date.

To deliver on its commitment to building a sustainable health security architecture, the US should heed the recommendations of these groups and prioritize driving forward the creation of a financing mechanism to mobilize global funding for pandemic preparedness and response and streamline its deployment across relevant institutions and networks. The US could work with a few allied governments to get the funds in motion, at least $5 billion to start, drawing on non-aid financing that befits this strategic health security and economic priority.

The administration deserves credit for taking a central role on the global stage. We’ll look forward to signs of additional progress at the promised second global COVID-19 summit.

Build better biopreparedness and expand resilience for biological threats

While it falls under the “international” goal seven in President Biden’s strategy this objective primarily involves taking action domestically. First and foremost, the strategy makes clear that the administration recognizes biological risks are increasing due to a variety of factors (increased zoonotic disease spillover, climate change, etc.). Reconstituting both White House and administration-wide infrastructure designed to monitor and respond to these emerging biological risks was a critical early step under this banner.

In August 2021, the CDC stood up a new Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics to improve US preparedness and modernize global early warning and trigger systems. In October, the Center made its first investments of $26 million to several academic institutions and collaborative efforts to support the development of infectious disease models and tools, an important resource for global health decisionmakers during COVID and beyond.

The administration unveiled a new plan called the “ American Pandemic Preparedness: Transforming Our Capabilities”-expected to cost $65.3 billion-to invest heavily in US biodefense, which would include vaccine, therapeutic, and diagnostic capabilities, early threat detection and forecasting, strengthening public health systems, and establishing strong mission management of these efforts.

This plan, and the administration- ordered whole-of-government review and update of US national biopreparedness policies was meant to culminate in the release of a strategy on biodefense and pandemic readiness, but we’re still waiting on its release.

The administration unveiled a new plan called the “ American Pandemic Preparedness: Transforming Our Capabilities”-expected to cost $65.3 billion-

There’s little question that the pandemic underscored weaknesses in supply chains-medical supply chains in particular-around the world.

Increasingly, the White House has taken actions intended to ease domestic supply chain constraints. Looking toward a more resilient future, the administration should broaden its approach, supporting greater transparency and diversification for supply chains that deliver critical medical supplies overseas. One sticking point is the geographic concentration of suppliers (and the substantial amount of capital it takes for a firm to develop a new supplier base). Agencies-such as DFC-could wield US-backed finance to incentivize domestic firms to expand and diversify their supplier base internationally, demonstrating value to not only US manufacturers and importers but also the industrial base of countries currently isolated from global supply chains. And new global health security financing could provide strategic support to the coalitions and firms developing regional manufacturing capabilities around the world.

More is needed

A year later, the administration has made clear progress toward several of the international objectives identified in its January 2021 strategy. It deserves credit for what it has accomplished, but sadly the pandemic’s advance has far outpaced international efforts to contain it.

The good news is that we have more tools and information than we did in the early days of the pandemic.

Nevertheless, far greater US investment and leadership will be required to get control of COVID-19 in the United States and around the world.

In parallel, the US must continue to push for improvements in global health security, including the creation of a financing mechanism to incentivize countries to enhance preparedness and perhaps even a bold new initiative, that will leave the United States and the world better prepared to face future health threats.

Originally published at https://www.cgdev.org.