This is a republication of the BBC Article about the BMA reports (one and two), edited by author of the blog . After the BBC article you will find an Executive Summary of both BMA reports.

Editor: Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

The UK government failed in its duty of care to protect doctors and the wider healthcare workforce at the start of the pandemic, a doctors’ union says.

BBC News

BMA — British Medical Association

May 18, 2022

The UK government failed in its duty of care to protect doctors and the wider healthcare workforce at the start of the pandemic, a doctors’ union says.

The British Medical Association review said staff were desperately let down by the lack of protective equipment.

And they were still suffering the physical and mental health impacts, having seen levels of illness and death “they were never trained for”.

The government said lessons would be learned but defended its record on PPE.

The BMA criticisms, based on feedback and testimonies from the union’s members, will form part of its submission to the official public inquiry into the pandemic.

Although healthcare is a devolved political issue, the UK government took on the role of making deals with PPE suppliers in order to supply equipment that was distributed across all four nations of the UK.

Doctors told the BMA that, during the early months of the pandemic, there were times they had to buy or make their own masks.

And some reported being left with long-term health problems from Covid infections.

‘My life as I knew it ended’

One junior medic, in Scotland, said they remained bedbound, after being infected in March 2020.

“My life as I knew it had ended,” the medic said.

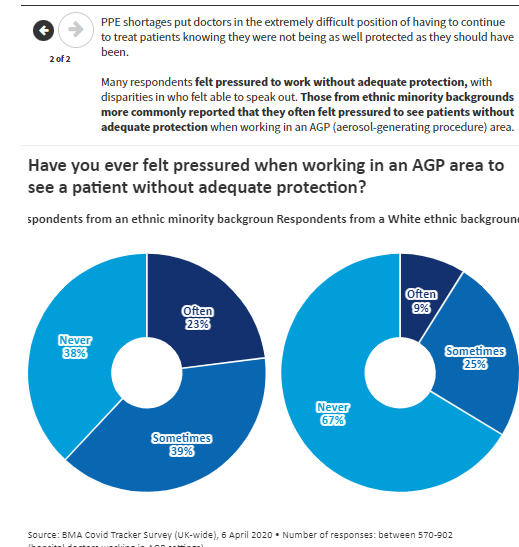

Many doctors said they had felt pressured to work in hazardous situations, with inadequate risk assessments.

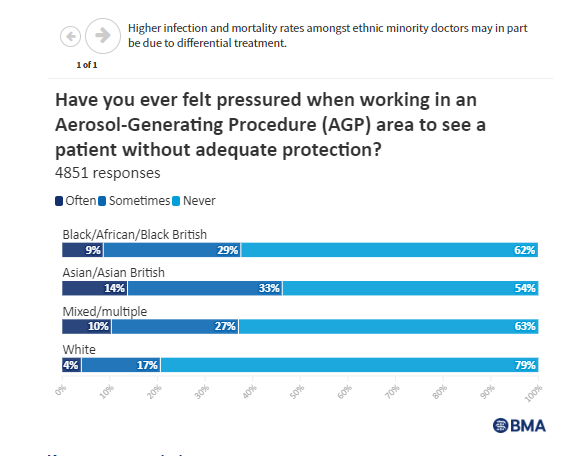

The review also highlighted how doctors with an ethnic minority background had been more likely to die with Covid, in the early stages of the pandemic, than their white peers.

Overall, Office for National Statistics data shows that, throughout 2020, doctors were no more likely than the general working-age population to die with Covid.

But nurses and care workers were at higher risk — although, it is unclear how much that was related to exposure at work rather than other factors.

… throughout 2020, doctors were no more likely than the general working-age population to die with Covid.

But nurses and care workers were at higher risk …

The BMA, which has been critical of the government’s response to the pandemic throughout, said the UK should have been better prepared and the problems had been made worse by the “savage” cuts to the public-health budget in the years before.

The BMA, which has been critical of the government’s response to the pandemic throughout, said the UK should have been better prepared and the problems had been made worse by the “savage” cuts to the public-health budget in the years before.

BMA leader Dr Chaand Nagpaul said: “A moral duty of government is to protect its own healthcare workers from harm in the course of duty as they serve and protect the nation’s health.

“Yet, in reality, doctors were desperately let down by the UK government’s failure to adequately prepare.”

“A moral duty of government is to protect its own healthcare workers from harm in the course of duty as they serve and protect the nation’s health.

“Yet, in reality, doctors were desperately let down by the UK government’s failure to adequately prepare.”

A government spokeswoman said enough PPE had been bought, in a “very competitive global market”, to keep staff safe and mental health hubs had been set up to help them cope with trauma.

But she added: “We are committed to learning lessons from the Covid pandemic and will respond openly and transparently to the Inquiry and fully consider all recommendations made.”

Originally published at https://www.bbc.com on May 19, 2022.

Names mentioned

BMA leader Dr Chaand Nagpaul

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION 1

COVID-19: The impact of the pandemic on the medical profession

The second of five BMA reports, each with a particular focus on the pandemic response

May 18, 2022

Our second COVID review report is the work of Olivia Clark, Margot Kuylen, Claire Chivers, Duncan Bland, Suzanne Wood, Lena Levy, Alex Gay and the BMA Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland teams.

Contributions have come from BMA elected members and chief officers. A huge team of people in our Communications and Policy Directorate and staff across the BMA made publication and promotion possible, including our strategic communications, media, public affairs and content and audience teams.

About this report

This report looks at the impact of the pandemic on the medical profession. It explores how the pandemic has affected their physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing, and to what extent adequate support was available.

It also discusses the financial consequences of COVID-19 for medical professionals and the pandemic’s impact on career progression for those in training.

The report will also look at some of the positive changes to the UK’s health services brought about by the pandemic, and how these changes might be maintained or restored.

Physical health

The pandemic seriously affected the physical health of medical professionals

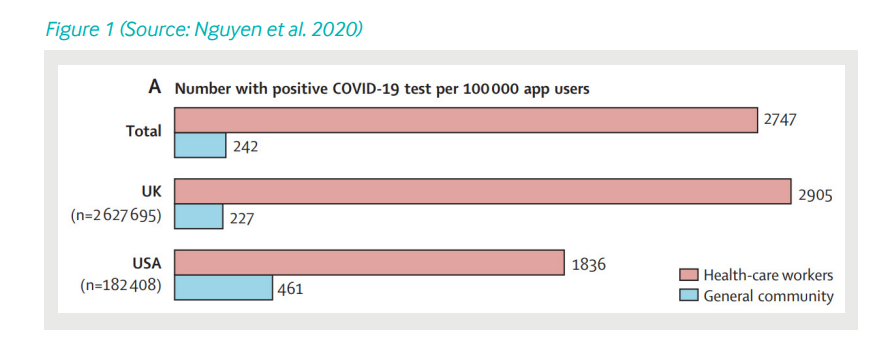

The pandemic posed an immediate threat to the physical health of medical professionals.

Those working on the frontline were and remain acutely vulnerable to COVID-19 infection.

Many caught COVID-19; a significant proportion of those developed long COVID and experienced severe and long-term symptoms.

Tragically, some doctors lost their lives while caring for others. Death rates may have been lower, and the impact of illness and seeing death of colleagues mitigated, had doctors been better protected and supported by the UK government and employers.

The physical effects of the pandemic were not felt equally among doctors.

Infection and mortality rates were higher amongst ethnic minority doctors, which may in part be due to differential treatment by others.

Key recommendations

- UK health services need good occupational health systems that can act quickly to protect staff both during and outside of health emergencies.

- To mitigate inequity in the future, mechanisms must be introduced to make the experience of working in the NHS less variable by background or protected characteristic.

Key recommendations on physical health:

(1) UK health services need good occupational health systems that can act quickly to protect staff both during and outside of health emergencies.,

(2) To mitigate inequity in the future, mechanisms must be introduced to make the experience of working in the NHS less variable by background or protected characteristic.

Questions for the inquiries

- What can be learned from the experiences of ethnic minority doctors, disabled doctors, and other groups during the pandemic?

How can we mitigate inequality in the UK’s health services? - How well were the UK’s health services able to support medical professionals who suffered from the short- or long-term health effects of COVID-19?

Mental health and wellbeing

The negative impact on mental health and emotional wellbeing

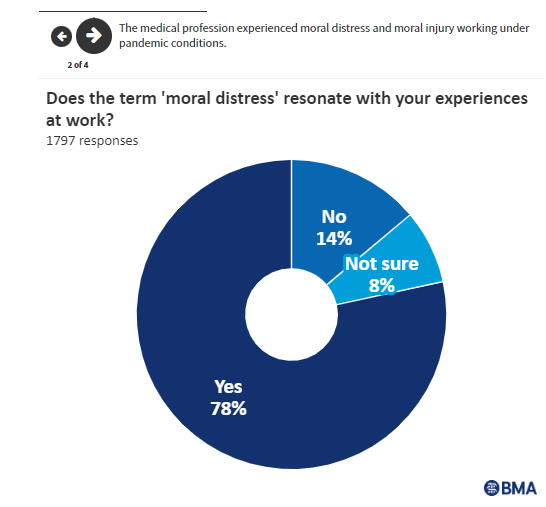

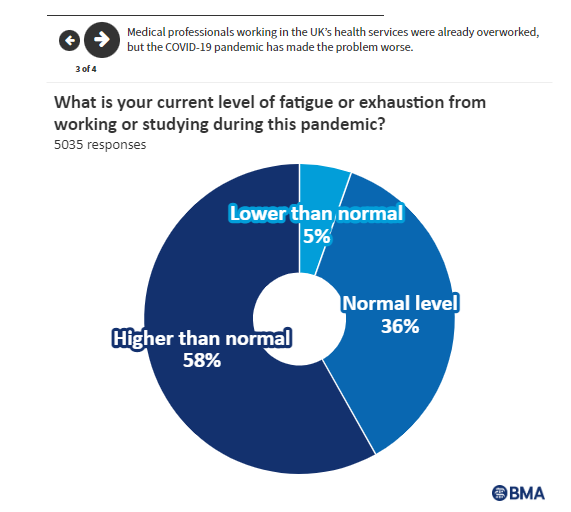

The pandemic has had a considerable impact on the mental health and emotional wellbeing of the medical profession.

Worryingly, this impact on staff mental health worsened as the pandemic progressed.

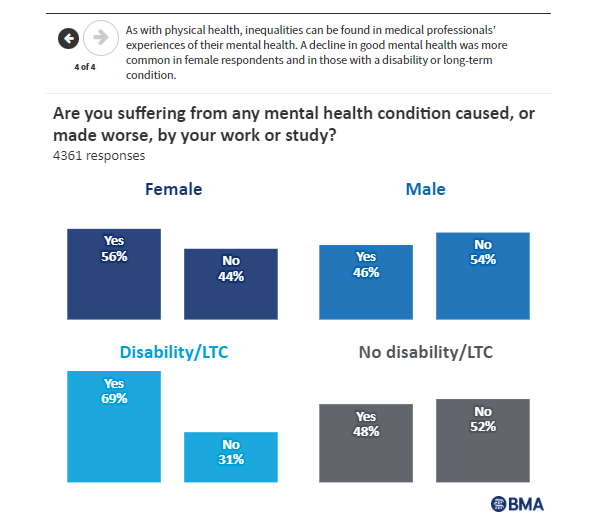

Many doctors suffered from mental health conditions like anxiety or depression, which were caused or made worse by the pandemic.

Often, the mental and emotional suffering of doctors was compounded by feelings of isolation.

The medical profession experienced moral distress and moral injury working under pandemic conditions, contributing to poor mental health outcomes.

In addition, fear of infection resulted in a sense of poor psychological safety among doctors. This was further compounded by the fear of passing the virus onto loved ones.

Finally, burnout and overwork have also significantly impacted on the wellbeing of medical professionals. Staffing shortages were often a contributing factor.

As with physical health, inequalities can be found in medical professionals’ experiences of mental health and burnout: a decline in mental health was more common in female respondents to our call for evidence and in those with a disability or long-term condition.

Key recommendations

- General wellbeing support must be made available for staff at all levels across all UK health services, along with specific support to recover from the pressure of delivering care during a pandemic.

- Continuous and transparent assessments of workforce shortages and future staffing requirements must be undertaken, to ensure Governments take accountability for providing safe staffing levels and fully resourcing it.

- All Governments and system leaders across the UK must have an honest conversation with the public about the need for a realistic approach to restoring non-COVID care, and support for doctors in tackling the backlog of care.

Key recommendations on Mental health and wellbeing:

(1) General wellbeing support must be made available for staff at all levels across all UK health services, along with specific support to recover from the pressure of delivering care during a pandemic,

(2) Continuous and transparent assessments of workforce shortages and future staffing requirements must be undertaken, to ensure Governments take accountability for providing safe staffing levels and fully resourcing it,

(3) All Governments and system leaders across the UK must have an honest conversation with the public about the need for a realistic approach to restoring non-COVID care, and support for doctors in tackling the backlog of care.

Questions for the inquiries

- How did the state of the UK’s health services going into the pandemic contribute to the impact of COVID-19 on the medical profession?

- Poor physical and mental health within the medical profession might be expected in a pandemic.

To what extent, though, could the negative impact experienced by doctors have been mitigated?

Support for doctors

Doctors did not always receive the support they needed

During the pandemic, medical professionals needed support more than ever. Too often, however, this support was not forthcoming.

A lack of publicly stated government support for doctors has damaged the image of staff working in UK health services and has resulted in medical professionals being subject to unrealistic expectations from patients and, in some cases, abuse.

In our call for evidence, a handful of respondents linked increased abuse by patients to poor government support.

In our call for evidence, a handful of respondents linked increased abuse by patients to poor government support.

Primary care staff in particular bore the brunt of the UK government’s failure to explain that the system, not the medical profession, was at fault for difficulties in accessing care.

Whilst doctors generally felt better supported by their employer, too many still did not receive the support they needed — especially those who were shielding or Clinically Extremely Vulnerable (CEV).

It is also clear that, due to chronic underfunding, occupational health services were not adequately equipped to look after doctors who needed help during the pandemic.

It is also clear that, due to chronic underfunding, occupational health services were not adequately equipped to look after doctors who needed help during the pandemic.

In addition, the pandemic impacted on the career and financial prospects of medical professionals.

Medical training was severely disrupted, often leading to delays in career progression, and some doctors lost significant proportions of their income due to factors like long covid or loss of locum work.

In addition, the pandemic impacted on the career and financial prospects of medical professionals.

Key recommendations

- Health education bodies across the UK must fund a model that supports adequate occupational medicine training posts to meet the level of demand in the UK’s health services now and in the future.

- Junior doctors and medical students must be assured that their efforts to support the delivery of care during the acute waves of the pandemic will not disproportionately affect their future careers.

They must be supported to flexibly access training opportunities to make up for those lost.

Key recommendations on Support for doctors:

(1) Health education bodies across the UK must fund a model that supports adequate occupational medicine training posts to meet the level of demand in the UK’s health services now and in the future.

(2) Junior doctors and medical students must be assured that their efforts to support the delivery of care during the acute waves of the pandemic will not disproportionately affect their future careers.

They must be supported to flexibly access training opportunities to make up for those lost.

Questions for the inquiries

- To what extent was the system able to protect staff from infection?

- To what extent was the system able to support staff who suffered any short- or long-term health effects from the pandemic?

Some initial positives

The pandemic also had some positive effects on the medical profession, at least initially

Despite the severe negative impact, the pandemic had some positive effects on the medical profession, such as a strong sense of team spirit and satisfaction from being able to help in times of crisis.

However, initial feelings of positivity and high morale amongst staff tended to wear off after the first wave.

As the crisis raged on, the backlog increased, and some doctors perceived that public support was waning.

Despite the severe negative impact, the pandemic had some positive effects on the medical profession, such as a strong sense of team spirit and satisfaction from being able to help in times of crisis.

However, initial feelings of positivity and high morale amongst staff tended to wear off after the first wave.

Key recommendations

- As far as possible, changes to the health services made since March 2020 that made a positive impact on doctors, such as hybrid working, should be retained or brought back to improve staff health, morale and retention rates.

Key recommendations on positive impacts:

As far as possible, changes to the health services made since March 2020 that made a positive impact on doctors, — such as hybrid working- should be retained or brought back to improve staff health, morale and retention rates.

Questions for the inquiries

- What were some of the positive changes brought about because of COVID-19, and how might some of them be maintained or restored?

COVID-19: The impact of the pandemic on the medical profession

About this report This report looks at the impact of the pandemic on the medical profession. It explores how the…www.bma.org.uk

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION 2

COVID-19: How well-protected was the medical profession?

The first of five BMA reports, each with a particular focus on the pandemic response.

BMA

May 18, 2022

Our first COVID review report is the work of Nathan Trotter, Claire Chivers, Margot Kuylen, Duncan Bland, Lena Levy, Alex Gay, and the BMA Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland teams.

Executive summary

How well was the UK’s medical profession protected from COVID-19 during the pandemic?

In late 2021, the BMA conducted a call for evidence survey to set out the experience of the medical profession during the pandemic and to learn lessons for future pandemics.

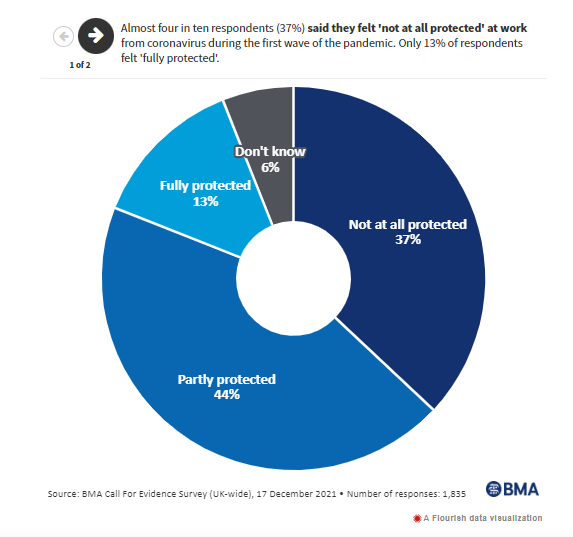

We found that doctors were not sufficiently protected during the pandemic:

- During the first wave of the pandemic in particular, medical professionals were often without the recommended level of PPE (Personal Protective Equipment), and without widespread access to testing or risk assessments.

81% of our 2,484 respondents reported that they did not feel fully protected during the first wave.

- Chronic underinvestment in the health services and public health systems across the UK meant that the UK was not as well prepared as it could have been as it entered the pandemic.

Key findings from exercises on pandemic preparedness were not fully acted upon.

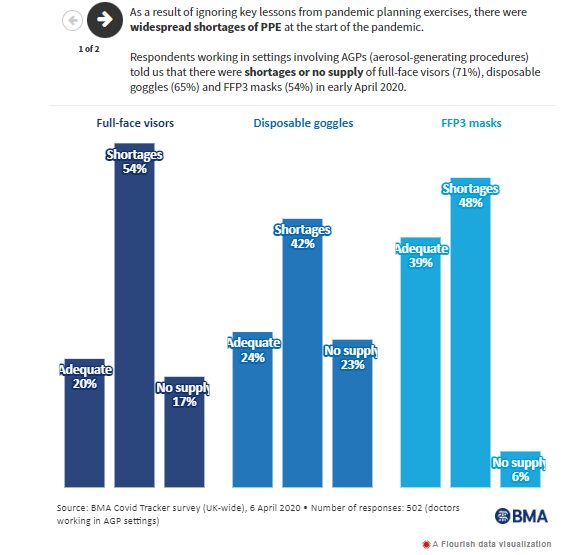

- There were real shortages of PPE at the start of the pandemic, shortages that could have been alleviated by prompter action and better management of the stockpile.

- UK-wide guidance did not respond quickly enough to the changing evidence base on PPE and testing, leaving many medical professionals exposed to an airborne virus without proper RPE (Respiratory Protective Equipment).

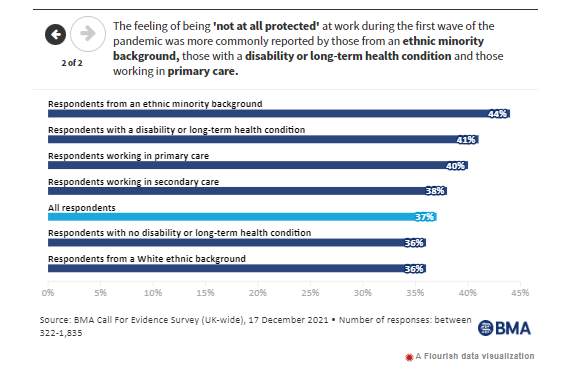

- Some doctors were particularly poorly protected.

Female doctors often struggled with poorly fitting PPE that left them exposed.

Doctors from ethnic minority backgrounds disproportionately reported that they felt risk assessments were less effective, compared to their white colleagues.

- There has been a significant level of distrust caused by the pandemic and the UK Government’s response among the medical profession.

- The vaccination campaign is regarded as one of the few successes of the response to the pandemic.

The speedy rollout helped protect medical professionals, and fostered pride in doctors due to their integral role in delivering vaccinations and protecting their communities.

About this report

This report looks at how well the medical profession across the UK was protected from COVID-19. It explores whether the protection afforded to medical professionals was suitable and sufficient to counter the substantial risk to which they were being exposed.

Health systems

The wider health and public health systems entered the pandemic under-resourced

Before the pandemic, health systems across the UK were operating in an environment of scarcity; general health spending was below that of comparable countries and there were chronic shortages of nurses, doctors and beds.

A better staffed and better resourced system would have been more able to deal with the acute spike in demand and high staff absence rate caused by the pandemic.

Key recommendations

- Maintain adequate workforce, investment, and future workforce plans including how many staff are needed to meet current and future demands,

- Improve capital investment, modernise physical infrastructure and improve ventilation of the NHS estate by implementing clear standards, with funding and equipment to meet them.

Key recommendations on Health systems:

(1) Maintain adequate workforce, investment, and future workforce plans including how many staff are needed to meet current and future demands,

(2) Improve capital investment, modernise physical infrastructure and improve ventilation of the NHS estate by implementing clear standards, with funding and equipment to meet them.

Pandemic planning

Key lessons from pandemic planning exercises were ignored

While there had already been two coronavirus pandemics in the 21st century, the UK Government prepared for the ‘wrong’ kind of pandemic by assuming that the major risk to public health was from an influenza-style pandemic. Preparations therefore centred on the treatment of disease rather than strategies to detect and contain potential cases.

Moreover, the UK and devolved governments conducted several pandemic planning exercises prior to COVID-19 and yet failed to act on the some of the key recommendations, particularly those related to stockpiles of PPE.

Key recommendations

- UK and devolved governments should continue to carry out pandemic preparedness exercises for the most likely types of infections.

- UK and devolved governments must act on the lessons learned.

Key recommendations on Pandemic planning:

(1) UK and devolved governments should continue to carry out pandemic preparedness exercises for the most likely types of infections,

(2) UK and devolved governments must act on the lessons learned.

Questions for the inquiries

- How was the initial policy response to the pandemic decided?

- How much influence did previous exercises have on the Government’s approach?

Infection prevention and control

Guidance on infection prevention and control (IPC) was inadequate, poorly communicated and difficult to implement

IPC guidance was slow to be released and slow to adapt to a rapidly changing situation. The guidance was often unclear, contradictory, poorly communicated and difficult to implement at a local level. It was also out of step with international organisations such as the WHO (World Health Organisation) and ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control).

Moreover, it did not remind employers of their pre-existing obligations under health and safety law and was not updated in light of evidence demonstrating that transmission occurred through actions such as coughing and breathing, rather than only during aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs).

As of report publication, healthcare workers in the UK are still being denied the appropriate level of protection when treating COVID-19 positive patients.

Key recommendations

- Ensure health and safety law is adequately publicised, enforced and promptly supported by appropriate guidance.

- IPC guidance should be updated rapidly in response to fast-changing situations and evidence, be communicated effectively, and highlight existing rights and responsibilities under health and safety law.

- Ensure there is a supportive culture across the wider health system so all feel able to speak out and raise their concerns.

Key recommendations on Infection prevention and control:

(1) Ensure health and safety law is adequately publicised, enforced and promptly supported by appropriate guidance.

(2) IPC guidance should be updated rapidly in response to fast-changing situations and evidence, be communicated effectively, and highlight existing rights and responsibilities under health and safety law,

(3) Ensure there is a supportive culture across the wider health system so all feel able to speak out and raise their concerns.

Questions for the inquiries

- What was the process for consulting stakeholders about the IPC guidance and how did this change over the course of the pandemic?

- What does the IPC Cell understand the role of airborne transmission to be? Why was guidance around aerosol transmission updated then revoked?

COVID testing

Testing capacity was insufficient at the beginning of the pandemic

The UK Government drastically overestimated the UK’s capacity to perform COVID-19 tests at the pace and to the volumes required. This initial lack of capacity meant that even though testing was reserved for health and social care settings, there were not enough tests for all patients who needed one. This had severe implications for many people living in care homes due to the lack of testing available for patients being discharged.

Key recommendations

- Public health systems should be resourced and funded to have adequate contact tracing capacity.

- Systems should be able to rapidly scale up testing for future variants or pandemics.

Key recommendations on COVID testing:

(1) Public health systems should be resourced and funded to have adequate contact tracing capacity,

(2) Systems should be able to rapidly scale up testing for future variants or pandemics.

Questions for the inquiries

- How long into the first wave did it take governments to understand that mass testing was of critical importance in controlling COVID-19?

PPE

PPE (personal protective equipment) supplies were insufficient, and processes for training and ensuring safe fit were inadequate

The initial stages of the pandemic saw widespread PPE shortages. The subsequent scramble to secure more supplies led to PPE being procured from organisations with no experience, deliveries of PPE that were unsuitable for use and a lack of transparency surrounding the deals struck to source PPE.

This meant that medical professionals on the frontline often had to go without PPE, reuse single-use items, use expired PPE or use homemade and donated items.

Many also felt pressured to work without adequate protection, with disparities in who felt able to speak out.

Key recommendations

- Maintain an adequate rotating stockpile of PPE and have plans to quickly scale up procurement and manufacturing if required.

- The medical workforce is diverse which means the PPE we procure needs to be suitable to different face and body shapes, varying hair textures, head coverings, and facial hair so all workers can access adequate protection.

- PPE should be provided with centrally coordinated guidance and practical training on how to fit test, use, and dispose of it safely.

Key recommendations on PPE:

(1) Maintain an adequate rotating stockpile of PPE and have plans to quickly scale up procurement and manufacturing if required,

(2) The medical workforce is diverse which means the PPE we procure needs to be suitable to different face and body shapes, varying hair textures, head coverings, and facial hair so all workers can access adequate protection,

(3) PPE should be provided with centrally coordinated guidance and practical training on how to fit test, use, and dispose of it safely.

Questions for the inquiries

- Why was the national stockpile not configured to deal with COVID-19?

- What needs to be done to ensure that the stockpile is appropriate to deal with a variety of threats?

Risk assessment

Risk assessments weren’t consistently carried out or implemented

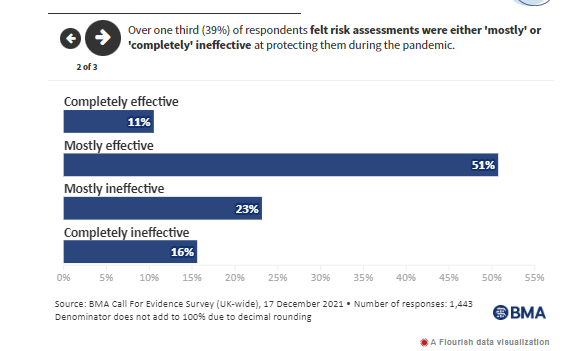

Many doctors were not risk assessed or their risk assessments were significantly delayed.

This left doctors unjustifiably exposed to COVID-19 and demonstrates how they were expected to carry on working regardless.

When risk assessments did take place, many doctors felt they were ineffective at protecting them; this was particularly the case amongst doctors working in hospital settings and those from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Key recommendations

- Carrying out risk assessments as required by law and acting upon them should be prioritised in all stages of a pandemic response.

- Invest in significantly increasing the occupational medicine workforce.

Key recommendations on risk assessment:

(1) Carrying out risk assessments as required by law and acting upon them should be prioritised in all stages of a pandemic response,

(2) Invest in significantly increasing the occupational medicine workforce.

Vaccination rollout

The vaccination programme was a success overall, with a few issues around early rollout

Medical professionals reported high levels of satisfaction with the vaccination programme and were rightly prioritised given their occupational exposure to COVID-19.

Some groups more commonly reported difficulties in accessing their first vaccination, particularly junior doctors, GP locums, medical students who were not yet deployed and doctors working in private practice.

In some cases, non-patient-facing staff and management were able to book and receive their vaccine before patient-facing staff, which was an understandable source of frustration for some.

Overall the vaccination rollout was however perceived positively with many medical professionals rightly proud of the role they played in making it happen.

Overall the vaccination rollout was however perceived positively with many medical professionals rightly proud of the role they played in making it happen.

Key recommendations

- Vaccine procurement was a massive success and should be used as a model for how to effectively fund scientific research in a fast-moving situation.

- Any future vaccination programmes should consider the range of potential barriers to access which could be experienced and identify ways to ensure access is equitable.

Key recommendations on vaccination rollout:

(1) Vaccine procurement was a massive success and should be used as a model for how to effectively fund scientific research in a fast-moving situation,

(2) Any future vaccination programmes should consider the range of potential barriers to access which could be experienced and identify ways to ensure access is equitable.

Questions for the inquiries

- What can be learned from the enormous success of the vaccine rollout and critical role played by the NHS and medical profession to better facilitate future public health campaigns?

COVID-19: How well-protected was the medical profession?

About this report This report looks at how well the medical profession across the UK was protected from COVID-19. It…www.bma.org.uk