Depression is a global health crisis

Recognising depression as a central yet neglected global health problem led to the creation of this Commission.

Time for united action on depression: A Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission

The Lancet

Prof Helen Herrman, MD *; Prof Vikram Patel, PhD *; Christian Kieling, MD *; Prof Michael Berk, PhD †; Claudia Buchweitz, MA †; Prof Pim Cuijpers, PhD †; et al.

February 15, 2022

This is an excerpt of the publication above, focused on the topics “Introduction” and “Whats is depression”?

Executive Summary

See the original publication

INTRODUCTION

“When you have other diseases, they are considered normal. Why is depression not considered a normal disease?”Vidushi Karnatic, age 20 years (Haldwani, India)

Over the past decades, much has been achieved in the field of global mental health. 1

The consequences of mental health problems are recognised globally and promising strategies have been devised to address them, even in low-resourced settings.

The value of mental health and its interconnections with sustainable development are better understood.

Mental health is central and intrinsic to overall health, exemplified by the inclusion of mental health in the UN Sustainable Development Goals. 1

Innovative ways of engaging communities and implementing services hold promise for expanded health promotion, prevention, and treatment opportunities around the world.

However many challenges remain.

Despite robust evidence of the effectiveness of several intervention strategies at multiple levels of promotion, prevention, treatment, and support, poor understanding of mental health and mental ill-health and high levels of stigma and discrimination continue to hamper public action.

There is no compelling evidence of a reduced burden of these conditions in any society, and most people affected by mental health problems do not receive appropriate interventions.

There is no compelling evidence of a reduced burden of these conditions in any society

No mental health condition captures the complexity of these challenges as emphatically as does depression, the leading mental health contributor to the Global Burden of Disease. 2

Metaphors such as “low spirits” 3 or “sadness and dejection” 4 have been used throughout human history to describe the experience of depression.

These terms reflect the omnipresence of the experience, as well as the difficulty in a narrow, discrete framing of the features associated with a condition comprising diverse sets of deeply personal experiences. 5

Operational definitions and classification systems have been essential in creating a common language for science and practice.

However, use of these definitions and systems can sometimes be seen to deflect attention from the unique journey of each individual affected by the disorder and to give insufficient weight to the voices of people with lived experience.

The concept of depression as used in medicine and health care refers to a condition that arises from multiple constellations of factors that operate in various ways with widely different outcomes.

Different combinations of factors predispose to and precipitate the onset of an episode; lead to different experiences and clinical presentations of the disorder with diverse trajectories; and respond to a wide range of prevention and treatment strategies, although with little indication so far of which strategy works better for whom and in which circumstances.

In this Commission we use two expressions to denote the lived experience of depression — people with depression and patients.

The term patients refers to people with clinical encounters and constitutes a subgroup of people with depression.

The concept of depression as used in medicine and health care refers to a condition that arises from multiple constellations of factors that operate in various ways with widely different outcomes.

Several core features of depression are identified across various geographies and cultures.

However, the heterogeneity is evident from the multiple ways in which symptoms combine to produce a variety of clinical phenotypes. 6

In extreme circumstances, two individuals can meet criteria for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder without sharing any single symptom. 7

Such variability leads to the question of whether depression is one disorder with shades of severity and multiple presentations, or whether it is a common name for a number of loosely related problems. 8

This diversity is further complicated by the fact that many of the core features of depression are also part of the normative human response to adversity, without a clear defining line between everyday sadness or distress and the clinical condition.

Unsurprisingly, the quest to determine a single cause for depression has been unsuccessful. Approaches to understanding the multi-causal origins of the condition analogous to those used in other non-communicable diseases have been much more useful and appropriate. 9

Although the biological underpinnings of depression must be acknowledged, and depression can be conceptualised ultimately as an illness of the brain, 10 recognising the tangible and intangible environmental influences on brain development and function across the lifespan are essential.

For example, research on childhood abuse and neglect emphasises the lasting effects on the risks for depression not only in childhood and adolescence, but also later in life and in subsequent generations. 11

… the quest to determine a single cause for depression has been unsuccessful.

These results make it clear that the pathways to experiencing depression can begin many years before the condition manifests.

The journey almost always involves environmental influences on neurodevelopment, psychological functioning, and neural circuits and networks, which in turn mediate the specific phenomena associated with the condition. 12

Researchers, practitioners, and those with lived experience have long worked to build a knowledge foundation for our understanding of this complex and heterogeneous human experience.

Depression has profound effects on a person regardless of sex, background, social class, or age.

It is associated with challenges and multi-faceted disability, with the early age of onset contributing to difficulties in adult functioning.

A proportion of those affected have a recurrent or persistent course, frequent co-occurrence of other health conditions, and an elevated risk of premature death from a range of causes including suicide.

Beyond the individual, depression can have an impact on families and communities and is an important barrier to the sustainable development of nations.

Given the degree of individual suffering and the deleterious effects on public health and society, asserting that depression is everybody’s business and a global health priority is important.

Given the degree of individual suffering and the deleterious effects on public health and society, asserting that depression is everybody’s business and a global health priority is important.

Yet, despite the abundant evidence reviewed later in this Commission that much can be done to prevent depression and facilitate recovery, only a small minority of the world’s population benefits from this knowledge.

In this regard, depression is a global health crisis.

This crisis is due in part to the controversies that rage around the nature of depression, its importance as a biomedical condition, and how depression should be managed.

There is a tension between depression constituting a medical entity and a leading cause of disability worldwide versus the construct of depression as an extreme of the normative emotional experience that should not be pathologised. 13

Critics question the application of the concept of depression and associated treatment science, mostly developed in European contexts, in diverse cultural settings around the world. 14

Other critiques question the extent to which conceptualising depression as a biological disorder with implications for use of medications is simply a ploy for reification of normal human suffering under a medical model and promotion of the pharmaceutical industry. 15

Recognising depression as a central yet neglected global health problem led to the creation of this Commission.

|

This Commission has a mandate to present a unifying and balanced view of the available evidence on these and other core questions, also indicating the grey areas and knowledge gaps requiring further research.

Audiences include people with the lived experience of depression and their families, clinical and public health practitioners, researchers, and policy makers.

The Commission aims to

- advance understanding of the nature of depression, laying to rest nihilistic debates — such as the idea that depression is simply sadness, that it is a creation of biomedicine, or that its roots are either biological or social —

- and providing evidence that depression can be prevented and treated if we move beyond a one-size-fits- all approach, which does not work well for depression nor a range of other health conditions.

Recognising the subtleties of each person’s experience of depression and the varying patterns in different population groups and cultural settings across the world is an essential step.

This recognition improves the ability to communicate information about the disorder to a broader audience, 16 enhancing understanding and reducing stigma.

Recognising depression as a central yet neglected global health problem led to the creation of this Commission.

The Commission emphasises the prospect of prevention and access to collaborative care strategies, even in resource-limited settings.

Thus, the Commission marks a historic opportunity for united action by all stakeholders across sectors, to work together and reduce the global burden arising from depression.

The Commission emphasises the prospect of prevention and access to collaborative care strategies, even in resource-limited settings.

SECTION 1: WHAT IS DEPRESSION?

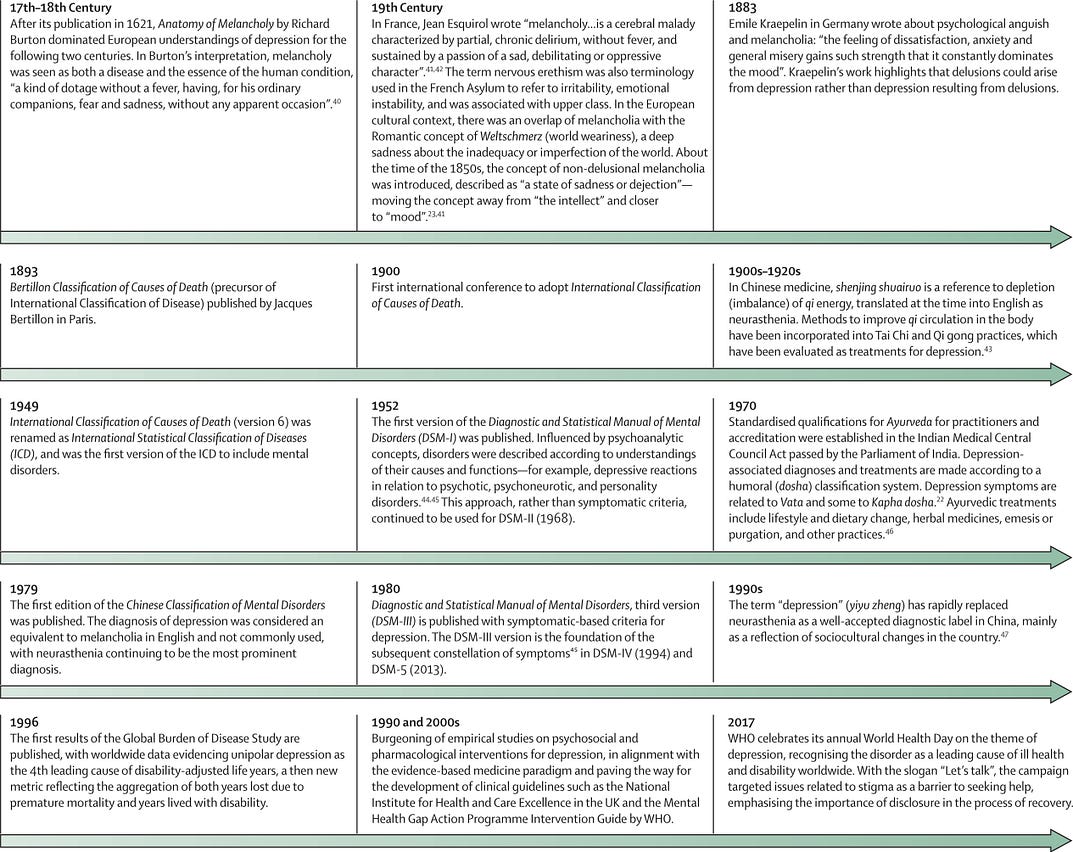

People have described different forms of suffering that resemble depression over thousands of years.

Across cultures that developed written medical text — Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, Qur’anic medicine, and Greco-Roman Classical Antiquity — symptoms of depression are described and remedies outlined.

These are underpinned by varied concepts of causation and vulnerability (figure 1).

Current diagnostic approaches

WHO’s 11th revision of its International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) 48 conceptualises depression as a syndrome (ie, a clinically recognisable set of reported experiences (symptoms) and observed behaviours (signs) associated with distress and interference with personal functions. 49

ICD-11 conceptualises depression as a syndrome… and observed behaviours (signs) associated with distress and interference with personal functions.

For a diagnosis of depression, at least five of a list of ten symptoms or signs have to be present most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks (panel 1).

PANEL 1: ICD-11 and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for depressive episode*

International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th revision (ICD-11)

- Depressed mood as reported by the individual (eg, feeling down, sad) or as observed (eg, tearful, defeated appearance). In children and adolescents, depressed mood can manifest as irritability.

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities, especially those normally found to be enjoyable to the individual (eg, a reduction in sexual desire).

- Reduced ability to concentrate and sustain attention to tasks or marked indecisiveness.

- Beliefs of low self-worth or excessive or inappropriate guilt that might be manifestly delusional.

- Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation (with or without a specific plan), or evidence of attempted suicide.

- Substantially disrupted sleep (delayed sleep onset, increased frequency of waking up during the night, or early morning awakening) or excessive sleep.

- Substantial change in appetite (diminished or increased) or substantial weight change (gain or loss).

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down).

- Reduced energy, fatigue, or marked tiredness following the expenditure or only a minimum of effort.

- Hopelessness about the future.

American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5)

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report (eg, feeling sad, empty, or hopeless) or observation made by others (eg, appears tearful). In children and adolescents, this mood can manifest as irritability.

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day (as indicated by either subjective account or observation).

- Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others).

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which might be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick).

- Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide.

- Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day.

- Substantial weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (eg, a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month) or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day. In children, this can manifest as an inability to make expected weight gain.

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down).

- Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day.

The presence of either the first or the second symptom or sign is mandatory. The mood disturbance should result in substantial functional impairment (ie, functioning is only maintained through substantial additional effort). 48

The symptoms and signs should not be a manifestation of another medical condition (eg, a brain tumour), should not be due to the effect of a substance or medication, and should not be better explained by bereavement.

The list of symptoms and signs in panel 1 — almost identical to that proposed by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) since its 3rd edition (DSM-III) 50 — is based on the best available evidence.

In a sample of people attending outpatient clinics with a range of clinical diagnoses, all symptoms included in the DSM had a positive predictive value of more than 75 in differentiating people with a diagnosis of depression versus those without depression, with the first two symptoms on the list having the highest values. 49

“Hopelessness about the future”, the only symptom included in the ICD-11 but not in the DSMs, performed more strongly than about half of the DSM symptoms and signs in differentiating those with depression from those without depression. 51

A further symptom, “diminished drive”, outperformed almost all those that are currently listed, and should probably be added to the list. 51

Other symptoms and signs not included in these definitions — such as lack of reactivity of mood (ie, the individual’s mood does not improve even temporarily in response to positive stimuli), anger, irritability, psychic anxiety, and somatic concomitants of anxiety (eg, headaches and muscle tension) — also discriminated between people with depression and people without depression, but performed less well than did the symptoms and signs listed in the DSMs and ICD-11. 51

Continuous or categorical and the question of severity

More controversial than the list of symptoms and signs defining depression has been the number of symptoms or signs required for diagnosis in both the DSM and the ICD (at least five, one of which must be either depressed mood or diminished interest or pleasure).

Several studies 52 , 53 have reported that subthreshold depressions (ie, conditions characterised by the presence of less than five depressive symptoms or signs) did not differ from diagnosable depression with respect to variables such as the risk for future depressive episodes, the family history of mental illness (including depression), psychiatric and physical comorbidity, and functional impairment.

Nor has the clinical utility of the five-symptom threshold in predicting response to treatment been confirmed. 54 , 55

Most studies applying latent class analysis 56 support the notion of a continuity between subthreshold and diagnosable depression.

A possible exception is a “nuclear depressive syndrome,” 57 broadly resembling the melancholic subtype of depression, which appears to be qualitatively different from other forms of depression, with more common vegetative symptoms, higher frequency of suicide attempts, and higher risk for depression in siblings.

Whether melancholia represents a distinct disease entity or corresponds to the most severe manifestation of depression (in which further neural circuits are possibly recruited so that the clinical picture becomes more complex and with a more substantial biological component) remains open to debate.

However, the fact that several people with recurrent depression experience some episodes which are melancholic and some others which are not 58 seems to argue in favour of melancholia being the most severe manifestation of depression.

The notion that depression is continuous rather than categorical does not solve the threshold issue.

Should we extend the concept of depression to include normative sadness, (ie, “the sorrow that visits the human being when an adverse event hits his precarious existence”)? 59

Extending the concept in this way does not seem reasonable, because on the one hand it would reinforce current complaints about the medicalisation of normal sorrow, driving inappropriate and unnecessary treatment, 60 and on the other hand it might mislead people who are really depressed, who could regard their condition as a normal response to adversity, thus being discouraged from seeking appropriate help.

The need to establish a threshold for subsyndromal depression to distinguish it from ordinary feelings of sadness has been widely acknowledged, and different solutions have been proposed. 61

The most frequently adopted option has been to require at least one core depressive symptom (ie, either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure), most of the time for at least 2 weeks. 62

Notably, this option is endorsed in the depression identification questions of the Guidelines for the Treatment of Depression of the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 63 although the time frame suggested is within the past month. An alternative has been to experience any two depressive symptoms most of the time for at least 2 weeks, associated with evidence of social dysfunction. 64

The different levels of severity of depression also remain to be validly characterised.

The descriptions provided in the current diagnostic systems, based on the number and intensity of symptoms and the degree of functional impairment, are somewhat generic and lack empirical validation. In fact, the ICD and DSM definitions of “mild”, “moderate”, and “severe” depression are rarely used in ordinary clinical practice worldwide. Clinical trials also do not use these definitions and instead assess the severity of depression on the basis of the global score on a rating scale, usually the 17-item version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. 65

Even in clinical trials, there is variability in how the different levels of severity of depression are defined. 66 , 67

The use of a measurement instrument — such as the 9-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), 68 based on DSM criteria — has been proposed as a practical approach to addressing the questions of the threshold for subsyndromal depression and the assessment of the severity of depression.

The PHQ-9 is a brief self-report questionnaire that can be completed by the user in just a few minutes and then rapidly scored by the clinician.

It is the most widely used (in the global context) questionnaire for the assessment of nine symptoms of depression, each scored on a 4-point Likert scale.

Scores can be interpreted as a continuous measure of severity or categorised into degrees of severity of depression; scores less than 5 signify absence of depression or sub-threshold depression.

A meta-analysis 69 reported that sensitivity and specificity was maximized at a cutoff score of 10 or more in studies using a semi-structured diagnostic interview (29 studies, 6725 participants; sensitivity 0·88; specificity 0·85).

Furthermore, using only the first two items, which assess the core phenomena of depression (low mood and anhedonia), followed by the remaining questions only if either is endorsed, is associated with similar sensitivity and specificity (0·85). 69

The PHQ-9 is a brief self-report questionnaire that can be completed by the user in just a few minutes and then rapidly scored by the clinician.

Nonetheless, there is some evidence of variation in these psychometric properties across contexts and it is recommended that the instrument, like any other measure of depression, undergo systematic translation and adaptation followed by validation to establish appropriate local cutoffs. 70

The PHQ-9 has been proposed for routine assessment of depression in primary care settings 71 and shown to be sensitive to treatment response.

In the aforementioned approaches, the severity of depression is evaluated by adding up the scores for the individual depressive symptoms and signs. However, research based on the network perspective on psychopathology (which understands mental disorders as complex networks of interacting symptoms) suggests that the various symptoms and signs might not have the same weight in determining the severity of depression: “depression sum-scores don’t add up.” 72

Therefore, the nature of the depressive symptoms and signs might also need to be considered.

Relevant to this issue is the concept of complicated versus uncomplicated depression, in which complicated depression is characterised by at least one of the following symptoms or signs: psychomotor retardation, psychotic symptoms, suicidal ideation, and sense of worthlessness or guilt. T

he complicated or uncomplicated status was found to predict the severity of depression significantly better than did the standard number-of-symptoms measures. 73

The nature of the depressive symptoms and signs, in addition to their overall intensity, might also inform the selection of treatment — for example, the choice of pharmacotherapy versus cognitive behavioural psychotherapy. 74

Psychopathological oversimplification?

A concern voiced by both mental health and social science researchers 75 , 76 is that the previous translation of the concept of depression into operational terms might have involved a psychopathological oversimplification.

This line of thought argues that the subjective experience of people with depression is different from “normal forms of negative mood such as despair or sadness.” 76

Some support for this argument has come from the few studies in which people with depression were asked to describe their current experience in their own words, or to select from lists of adjectives those which best depicted their state.

The most common descriptions provided in one of these studies, 77 (“a feeling that the subject was coming down with a viral illness, either influenza or glandular fever, along with descriptions of aches and pains”; “a sense of detachment from the environment”; “a specific inability to summon up effort, a feeling of being inhibited or an inability to envisage the future”), as well as the adjectives they most commonly endorsed (dispirited, sluggish, wretched, empty, washed out, awful, dull, and exhausted), do suggest that the nature of the subjective experience of depression might not be fully conveyed by current diagnostic systems, and might involve a more substantial somatic component than currently maintained.

The aforementioned descriptions potentially might not be relevant to all or most people with depression, but only to a subgroup (ie, those with melancholia).

However, a systematic review of qualitative studies done on depression worldwide 78 found that several somatic symptoms — namely headaches, general aches and pains, problems connected with the heart (eg, palpitations, heavy heart, and heart pain) — were among the features most frequently reported by people with depression across populations.

A study based on the “network approach” 79 also found sympathetic arousal (ie, palpitations, tremors, blurred vision, and sweating) to be one of the most central symptoms in the depression network, showing strong connections with other somatic complaints (limb heaviness, pain, and headaches).

Higher order dimensions and specifiers

Depression often co-exists, at different levels of severity, with anxiety and bodily distress.

Studies in primary care settings have suggested that depressive, anxiety, and somatic symptoms might be different presentations of a common latent phenomenon 80 and might require common therapeutic approaches, 81 leading some to propose a higher order category of common mental disorders. 82

However, in a subpopulation (more frequently in men), depression might instead be part of an externalising spectrum, also including anger attacks, aggression, substance abuse, and risk-taking behaviour. 83

This characterisation should also consider what current diagnostic systems regard as specifiers or qualifiers to the diagnosis of depression, such as the presence of melancholic, atypical, or psychotic features; a peripartum onset; or a seasonal pattern of occurrence of depressive episodes.

In some instances, these features have specific treatment implications — for example, use of antipsychotics in the presence of psychotic features or the use of light therapy in seasonal depression. 84

In ICD-11, the qualifier “with melancholia” applies when several of the following symptoms have been present during the worst period within the past month: pervasive anhedonia, lack of emotional reactivity, terminal insomnia, depressive symptoms that are worse in the morning, marked psychomotor retardation or agitation, marked loss of appetite, or loss of weight. The qualifier “with psychotic symptoms” applies when either delusions or hallucinations are present during the episode.

Psychotic symptoms can be subtle or might be concealed by the patient, and the boundary between delusions and persistent depressive ruminations or sustained preoccupations might not be clear.

The latest edition of the DSM (DSM-5) 85 also includes the specifier “with atypical features” (absent in the ICD-11), which pertains to people who have increased appetite, weight, and sleep, as opposed to lack of appetite and insomnia.

The DSM and ICD approach of considering melancholic and psychotic features as specifiers or qualifiers to the diagnosis of depression, rather than assuming that melancholia and psychotic depression are distinct diagnostic entities, is also supported by the evidence that in many people with recurrent depression, some episodes are either psychotic or melancholic and others are not. 58 , 86

Since depression occurring within bipolar disorder does not seem to have distinct presenting features, the history of past manic or hypomanic episodes should be investigated in every person presenting with a depressive episode.

Bipolar depression is different from unipolar major depression in several important respects, including treatment needs and prognosis.

Ascertaining this history can considerably affect the management plan. 87

For example, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder can imply an increased risk of postpartum psychosis in the initial weeks after birth in women. 88

An issue which remains controversial is that of mixed depression (ie, a depressive syndrome accompanied by symptoms or signs of thought, motor or behavioural overactivation interpreted as contrapolar).

DSM-5 defines “major depressive disorder with mixed features” as a depressive episode with at least three typical manic symptoms or signs such as expansive mood, inflated self-esteem, or increased involvement in risky activities, present on most days.

By contrast, in the ICD-11 characterisation, the most common contrapolar features are irritability, racing or crowded thoughts, increased talkativeness, and psychomotor agitation, in line with both the classic 89 and recent 90 literature on this issue.

Both the ICD-11 and DSM-5 provide different codes for single episode depressive disorder and recurrent depressive disorder.

In ICD-11, recurrent depressive disorder is defined by a history of at least two depressive episodes separated by several months without substantial mood disturbance. Both diagnostic systems acknowledge that the remission after a depressive episode might be considered either partial or full. ICD-11 provides a qualifier indicating that the current depressive episode is persistent (ie, diagnostic requirements have been met continuously for at least the past 2 years), …

… whereas in DSM-5, persistent depressive disorder is a separate diagnostic entity. Dysthymic disorder is yet another variant characterised by persistent depressed mood and accompanied by typical symptoms of depression that never meet the diagnostic requirements for a depressive episode.

Age and gender

Depression among preschool children was not recognised until the early 2000s.

Although less common than at other ages, preschool-onset depression can display a persistent course through late adolescence, with multiple negative outcomes. 91

Considering adolescents, there is a widespread notion that moodiness, feelings of loneliness, interpersonal sensitivity, and negative self-perception are relatively common.

This perception has contributed to the neglect or even the denial of the problem of youth depression, despite its importance as a signal of the possibility of recurrent depression throughout the life course. 92

However, depressive symptoms might be part of the fluid and non-specific clinical picture that has been described as a prodromal stage of the development of several mental disorders. 93

In the ICD-11 and DSM classifications, the only emphatic difference in the clinical picture of depression among children and adolescents compared with in adults is that “depressed mood can manifest as irritability”. Beyond that, the ICD-11 text notes that the reduced ability to concentrate or sustain attention could manifest in adolescence as a decline in academic performance or an inability to complete school assignments. Adolescents with depression are often primarily irritable and unstable, with frequent anger outbursts, sometimes without provocation, which can result in a deterioration of their interpersonal relationships. 94 , 95

Moreover, they might not report sadness, but complain of feelings of disquiet and malaise that are overwhelmingly painful. 95

Ruminations about being unable to live up to school demands or about feeling different from others are common.

In many cases, conduct problems, eating disorders, substance abuse, or inattention at school can be the focus of relatives’ or teachers’ complaints.

Suicidality and self-injurious behaviours are particularly sensitive concerns in young people.

A further complication concerning young people is that depression usually precedes mania in bipolar disorder, so that the index presentation of this disorder in youth is often depression. 96

As in adolescents, depression among older people is often under-recognised or minimised. It is often ascribed to normal ageing, to losses, or to physical illness.

The clinical picture of depression in older people, compared with that in middle-aged adults, includes a higher frequency of somatic symptoms, anxiety, psychomotor retardation or agitation, and psychotic features.

Moreover, depression in older people is more commonly associated with cognitive impairment (particularly memory disturbances, impaired executive functions, or slowed information processing), painful conditions, and physical disability. 97

Depression is consistently found to be more common in women than in men. This gender difference is first apparent at about age 12 years, and has been found to peak in adolescence, at age 16 years. 98

Whether the gender gap decreases or not during older age is currently debated. 99

The clinical picture is reported to be similar in women and men except that, as noted earlier, externalising features are now recognised as more common in men. 83

Additionally, appetite changes, fatigue, and poor sleep can be associated with pregnancy and the post-partum, and are less discriminating for depression during the perinatal period. 100

Culture and depression

A challenge to understanding the generalisability of depression to the global context is that most research has come from high-income, predominantly English-speaking countries. Some authors critique that the concept of depression conveyed by the ICD is biased towards these populations.

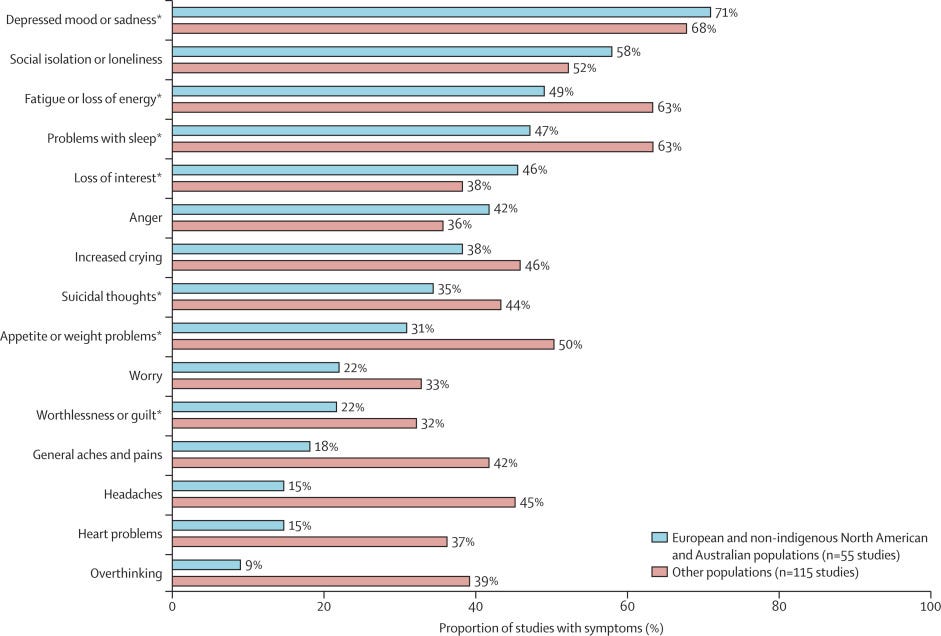

Studies of depression across history and cultures (Figure 1, Figure 2) suggest that while several core features of depression are clearly identified across geographies and cultures, substantial variations remain. For example, the prominence of sadness might not be universal, emotions are expressed in differing ways, and there is overlap between the concepts of social suffering and depression as a biomedical construct. 101 , 102

Figure 2 Depressive symptoms in diverse global populations

Cross-national studies using standardised diagnostic tools such as the Composite International Diagnostic Interview show that many of the ICD and DSM symptoms occur across cultures and populations. 103

However, contextually grounded research draws attention to other symptoms that are not routinely evaluated even though they might be salient for people presenting with depression and their health-care providers (eg, loneliness, anger, and headaches).

The higher prevalence of somatic symptoms (such as headaches and general aches and pains) among African, Asian, Caribbean, Central and South American, and Pacific Islander people and indigenous populations from North America, Europe, and Australia (figure 2), 78 might be associated with several factors.

Even though somatic complaints are rarely documented in studies, they might be discussed more readily than are cognitive and emotional challenges. 104 , 105

Irritability and anger are also not included within DSM criteria for adults, but are frequently noted across diverse cultural groups. 78 , 106 , 107

The subjective experience of loneliness is also a hallmark symptom in many cultural groups; 78 , 108 , 109 for example, among Aboriginal men in Australia, loss of social connection was a central feature of the depression experience with less salience of hopelessness and somatic complaints. 110

One notable finding suggested that depression was a relatively weak risk factor for suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts in low-income and middle-income countries, with a strong relationship between suicidality and depression found in high-income countries. 111

Cultural idioms of distress have been evaluated for similarities with ICD or DSM classifications of depression.6

These idioms include hwa-byung, shenjing shuairuo, and phiên não tâm thân in East and Southeast Asia; tension and heart-mind problems in South Asia; kufungisisa, kusuwisia, and yo’kwekyawa in sub-Saharan Africa; and susto, coraje, and nervios-related conditions in Latin America.

A meta-analysis examining the association of these concepts with ICD or DSM depression categories observed that people endorsing these idioms had 7·55 greater odds than did others of meeting the ICD or DSM depression criteria. 4

The idiom “thinking too much” denotes a broader mental health syndrome, with manifestations such as sadness, lack of motivation, poor concentration, sleep difficulties, and irritability, perhaps similar to the construct of common mental disorders. 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117

Use of these idioms and other cultural concepts has been central to the development and adaptation of psychological interventions for depression that are culturally acceptable and reduce risk of stigmatisation. 118 , 119 , 120 , 121

Use of the idioms can also be paired with depression screening tools to reduce screening time and improve accuracy of detection. 122

Unfortunately, cultural influences on the experience of depression among children and adolescents have rarely been studied. To date, some studies have suggested that symptoms such as appetite or weight changes do not distinguish between people with depression and people without depression outside of affluent high-resource settings, as shown by studies in Nigeria, Nepal, and Turkey. 122 , 123 , 124

Subjective experiences of loneliness are distinctive aspects of the phenomenology of depression among youth across cultural groups in high-income, low-income, and middle-income countries. 124 , 125 , 126

Depression and grief

The effect of grief is different from a depressed mood. It consists of feelings of emptiness and loss, but self-esteem is usually preserved. Dysphoria tends to occur in waves, usually associated with thoughts or reminders of the deceased, rather than being persistent. 56

However, both the ICD-11 and the DSM-5 acknowledge that depression might occur in some bereaved people.

The ICD-11 provides a higher threshold for the diagnosis of depression; a longer duration of the depressive state is required (a month or more following the loss, with no periods of positive mood or enjoyment of activities), as well as the presence of some symptoms which are unlikely to occur in typical grief (extreme beliefs of low self-worth and guilt not related to the lost loved one, psychotic symptoms, suicidal ideation, or psychomotor retardation).

This approach, present in the DSM-IV, has been abandoned in the DSM-5, in which the threshold for the diagnosis of depression is the same in bereaved and non-bereaved people.

The ICD-11 has also introduced the new category of prolonged grief disorder, including abnormally persistent and disabling responses to bereavement. 127

Following the death of a person close to the bereaved, there is a persistent and pervasive grief response characterised by longing for the deceased or persistent preoccupation with the deceased, accompanied by intense emotional pain. Symptoms might include sadness, guilt, anger, denial, blame, difficulty accepting the death, feeling that the person has lost a part of themselves, an inability to experience positive mood, emotional numbness, and difficulty in engaging with social or other activities. This response must clearly exceed expected social, cultural, or religious norms and, to attract the diagnosis, it must persist for more than 6 months following the loss. There is evidence that prolonged grief disorder, characterised as a stress disorder in DSM-5, responds well to a specific type of psychotherapy tailored for the condition. 128

Although the symptoms of prolonged grief disorder are observed across cultural settings, 129 grief responses can manifest in culturally specific ways, with diversity in the expected norms for duration of grieving. 130 , 131 , 132

Notably, studies of cultural concepts of grief among refugees demonstrate that the terms and explanatory models for prolonged grief are distinct from cultural concepts of depression. 133

Section 2 and other Sections

See the original publication

References

See the original publication

About the authors

Prof Helen Herrman, MD *;

Prof Vikram Patel, PhD *;

Christian Kieling, MD *;

Prof Michael Berk, PhD †;

Claudia Buchweitz, MA †;

Prof Pim Cuijpers, PhD †;

Prof Toshiaki A Furukawa, MD †

Prof Ronald C Kessler, PhD †

Prof Brandon A Kohrt, MD †

Prof Mario Maj, PhD †

Prof Patrick McGorry, MD †

Prof Charles F Reynolds III, MD †

Prof Myrna M Weissman, PhD †

Dixon Chibanda, PhD

Prof Christopher Dowrick, MD

Prof Louise M Howard, PhD

Prof Christina W Hoven, DrPH

Prof Martin Knapp, PhD

Prof Helen S Mayberg, MD

Prof Brenda W J H Penninx, PhD

Prof Shuiyuan Xiao, MD

Prof Madhukar Trivedi, MD

Prof Rudolf Uher, PhD

Lakshmi Vijayakumar, PhD

Prof Miranda Wolpert, PsychD

†Lead writing group Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Parkville, VIC, Australia (Prof H Herrman MD, Prof P McGorry MD);

Centre for Youth Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia (Prof H Herrman, Prof P McGorry);

Department of Global Health and Social Medicine (Prof V Patel PhD), Department of Health Care Policy (Prof R C Kessler PhD),

Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Sangath, Goa, India (Prof V Patel);

Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard T H Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA (Prof V Patel);

Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine (C Kieling MD),

Graduate Program in Psychiatry (C Buchweitz MA), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil;

Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Division, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil (C Kieling);

Deakin University, IMPACT Institute, Geelong, VIC,