Lown Institute

Judith Garber

April 18, 2022

The Choosing Wisely program was started in 2012 by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation to promote conversations between clinicians and patients on avoiding unnecessary tests, treatments, and procedures.

Medical specialty organizations asked their members to identify commonly used low-value tests or procedures and created lists of services to avoid along with patient resources.

Lown Institute president Vikas Saini reflected on what we’ve learned ten years after the start of Choosing Wisely, in an audio interview in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The interview accompanied a viewpoint piece on the same topic by Brigham and Women’s primary care doctor Elizabeth Rourke.

The impact of Choosing Wisely

Over the past decade, Choosing Wisely has expanded to include more than 80 specialty societies from 25 countries.

But what has the impact of the program been on actually reducing low-value care?

Choosing Wisely started out of concern about the quality and efficiency of our health care system, and from the desire for the medical community to start a conversation on overuse.

The program was a step for medical specialties to “own” their role in low-value care, said Saini.

To that end, Choosing Wisely’s growth shows increased interest and awareness within medical specialties about tests and procedures to avoid.

“There’s no question that Choosing Wisely was a really important icebreaker [on overuse”

Dr. Vikas Saini, NEJM

The program was a step for medical specialties to “own” their role in low-value care, said Saini.

When it comes to reducing actual rates of overuse, the impact of Choosing Wisely is more murky.

When it comes to reducing actual rates of overuse, the impact of Choosing Wisely is more murky.

Studies measuring usage of tests and procedures identified as low-value through Choosing Wisely found little change in the years since the program began.

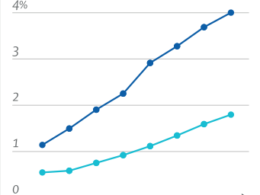

One study published last year in JAMA found that from 2014–2018, the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries receiving any low-value service declined — but only by 2.7%.

… from 2014–2018, the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries receiving any low-value service declined — but only by 2.7%.

In 2018, about one third of Medicare beneficiaries were still receiving at least one low-value service.

While low-value preventive screenings like annual cardiac screenings and Vitamin D screenings decreased, prescriptions of opioids for back pain increased, as did antibiotics for colds.

In 2018, about one third of Medicare beneficiaries were still receiving at least one low-value service.

While low-value preventive screenings like annual cardiac screenings and Vitamin D screenings decreased, prescriptions of opioids for back pain increased, as did antibiotics for colds.

While there hasn’t been a substantial systemic change in overuse rates from Choosing Wisely, researchers have identified promising interventions on a hospital level that were driven by this program.

A 2021 systematic review of overuse interventions found that programs such as clinical decision support, EHR alerts to warn about low-value services, and updating clinical practice guidelines, were much more impactful than just disseminating Choosing Wisely guidelines alone.

Why is overuse slow to change?

In NEJM, Dr. Elizabeth Rourke argued that the elements that made Choosing Wisely so popular are those that have made it ineffectual.

The program was designed to avoid the perception of healthcare “rationing” in the era of Obamacare, so there are no teeth to the recommendations.

Choosing Wisely allows specialty societies flexibility in choosing what goes on these lists; as a result, they tend to include imaging and testing that have less of an impact on their specialty’s bottom line.

The program was designed to avoid the perception of healthcare “rationing” in the era of Obamacare, so there are no teeth to the recommendations.

Choosing Wisely allows specialty societies flexibility in choosing what goes on these lists; as a result, they tend to include imaging and testing that have less of an impact on their specialty’s bottom line.

Saini agreed that taking a professional-led approach had inherent benefits and drawbacks for Choosing Wisely.

For example, the criteria used to create the recommendation lists varied widely across specialties, which let some specialties off the hook for avoiding talking about the most common or high-margin services.

In fact, this frustrating with some of the recommendations led the Right Care Alliance to develop their own specialty “Top Ten Dos and Don’ts” lists, some of which have been published in medical journals.

“The challenge is that overuse is a systemic problem.

It needs systemic solutions.”

Vikas Saini, NEJM

Despite some of the deficits of Choosing Wisely, the larger issue is that overuse is so deeply rooted, that it will take much more than a physician-led awareness campaign to create sustained and meaningful change.

“Using lists is helpful to a point, but you see the numbers on those lists are in the thousands,” said Saini.

That means that helpful interventions in one area of low-value care just seem like islands in an ocean of overuse.

Despite some of the deficits of Choosing Wisely, the larger issue is that overuse is so deeply rooted, that it will take much more than a physician-led awareness campaign to create sustained and meaningful change

A cultural shift

If programs like Choosing Wisely aren’t enough to get us to real change, then what is?

Part of the problem is economic; in our fee-for-service system, clinicians are rewarded for doing more, even when it doesn’t help patients.

“Economic factors drive rapid adoption of low-value care and impede ‘dis-adoption’ of procedures that have shown not to be particularly effective,” said Saini.

The movement toward value-based care, while slow-moving, is a promising change to realigning incentives toward health rather than volume.

Part of the problem is economic; in our fee-for-service system, clinicians are rewarded for doing more, even when it doesn’t help patients.

The movement toward value-based care, while slow-moving, is a promising change to realigning incentives toward health rather than volume.

There also have to be economic incentives for patients and communities as well as doctors.

“If we reduce low-value care, the money doesn’t go back to communities to invest in health,” Saini pointed out.

“If you don’t have parties who can clearly see how they gain, they’re not motivated.”

“If we reduce low-value care, the money doesn’t go back to communities to invest in health,” Saini pointed out.

Cultural factors — like the idea that “always doing something is better than doing nothing” — also play a role in driving overuse.

These assumptions are hard to change, especially because doctors have so little time with patients.

Without a trusting relationship, it’s much harder to explain why a test or procedure might be wrong for that patient.

Evaluating interventions for low-value care and scaling them up, changing how we pay for care, and giving clinicians and patients time to have these important conversations should all be top of mind as we rethink the best way to “choose wisely” in the future.

Evaluating interventions for low-value care and scaling them up, changing how we pay for care, and giving clinicians and patients time to have these important conversations should all be top of mind as we rethink the best way to “choose wisely” in the future.

Listen to the full NEJM audio interview with Dr. Vikas Saini!

Originally published at https://lowninstitute.org on April 18, 2022.

Brigham and Women’s primary care doctor Elizabeth Rourke.

Dr. Vikas Saini, NEJM

In NEJM, Dr. Elizabeth Rourke