Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings

JAMA Network

William H. Shrank, MD, MSHS1; Teresa L. Rogstad, MPH1; Natasha Parekh, MD, MS2

October 7, 2019

IMPORTANCE

The United States spends more on health care than any other country, with costs approaching 18% of the gross domestic product (GDP).

Prior studies estimated that approximately 30% of health care spending may be considered waste.

Despite efforts to reduce overtreatment, improve care, and address overpayment, it is likely that substantial waste in US health care spending remains.

OBJECTIVES

To estimate current levels of waste in the US health care system in 6 previously developed domains and to report estimates of potential savings for each domain.

EVIDENCE

A search of peer-reviewed and “gray” literature from January 2012 to May 2019 focused on the 6 waste domains previously identified by the Institute of Medicine and Berwick and Hackbarth: failure of care delivery, failure of care coordination, overtreatment or low-value care, pricing failure, fraud and abuse, and administrative complexity.

For each domain, available estimates of waste-related costs and data from interventions shown to reduce waste-related costs were recorded, converted to annual estimates in 2019 dollars for national populations when necessary, and combined into ranges or summed as appropriate.

FINDINGS

The review yielded 71 estimates from 54 unique peer-reviewed publications, government-based reports, and reports from the gray literature.

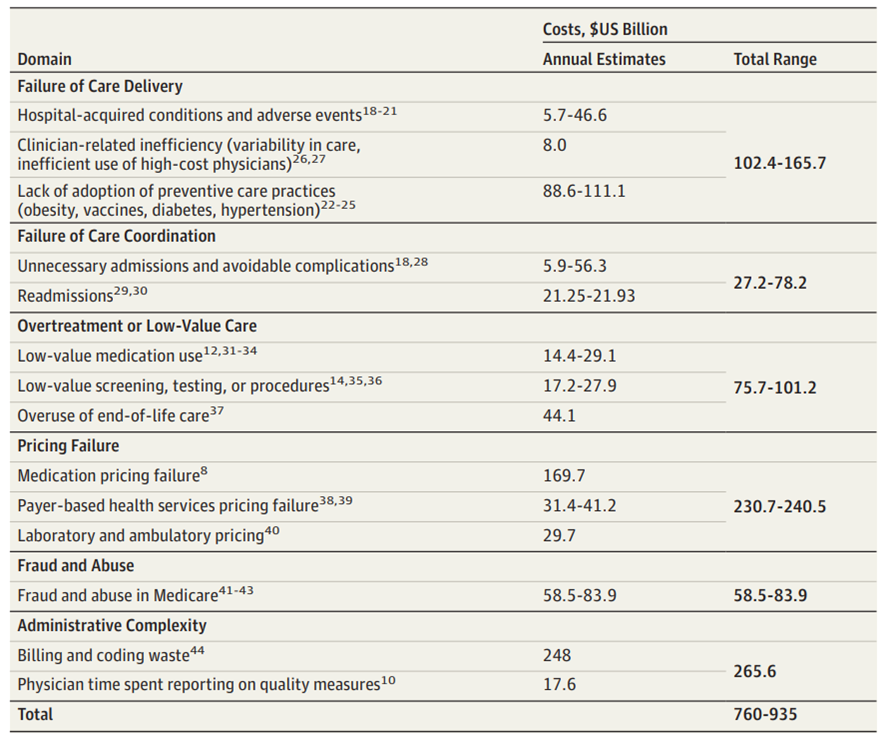

Computations yielded the following estimated ranges of total annual cost of waste:

· failure of care delivery, $102.4 billion to $165.7 billion;

· failure of care coordination, $27.2 billion to $78.2 billion;

· overtreatment or low-value care, $75.7 billion to $101.2 billion;

· pricing failure, $230.7 billion to $240.5 billion;

· fraud and abuse, $58.5 billion to $83.9 billion; and

· administrative complexity, $265.6 billion.

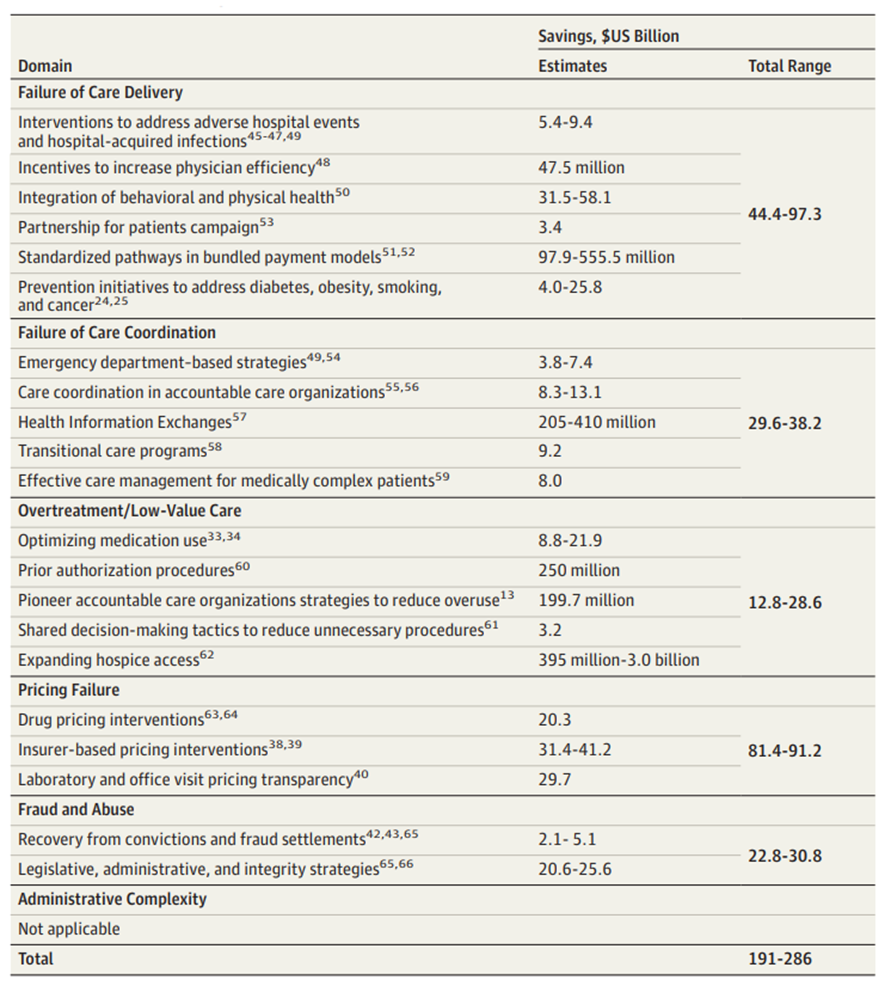

The estimated annual savings from measures to eliminate waste were as follows:

· failure of care delivery, $44.4 billion to $97.3 billion;

· failure of care coordination, $29.6 billion to $38.2 billion;

· overtreatment or low-value care, $12.8 billion to $28.6 billion;

· pricing failure, $81.4 billion to $91.2 billion; and

· fraud and abuse, $22.8 billion to $30.8 billion.

No studies were identified that focused on interventions targeting administrative complexity.

· The estimated total annual costs of waste were $760 billion to $935 billion

· and savings from interventions that address waste were $191 billion to $286 billion.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

In this review based on 6 previously identified domains of health care waste, the estimated cost of waste in the US health care system ranged from $760 billion to $935 billion, accounting for approximately 25% of total health care spending, …

… and the projected potential savings from interventions that reduce waste, excluding savings from administrative complexity, ranged from $191 billion to $286 billion, …

… representing a potential 25% reduction in the total cost of waste.

Implementation of effective measures to eliminate waste represents an opportunity reduce the continued increases in US health care expenditures.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (excerpt version)

Waste in the US Health Care System

Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings

JAMA Network

William H. Shrank, MD, MSHS1; Teresa L. Rogstad, MPH1; Natasha Parekh, MD, MS2

October 7, 2019

INTRODUCTION

The United States spends more on health care than any other country, with costs approaching 18% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and more than $10 000 per individual.[1]

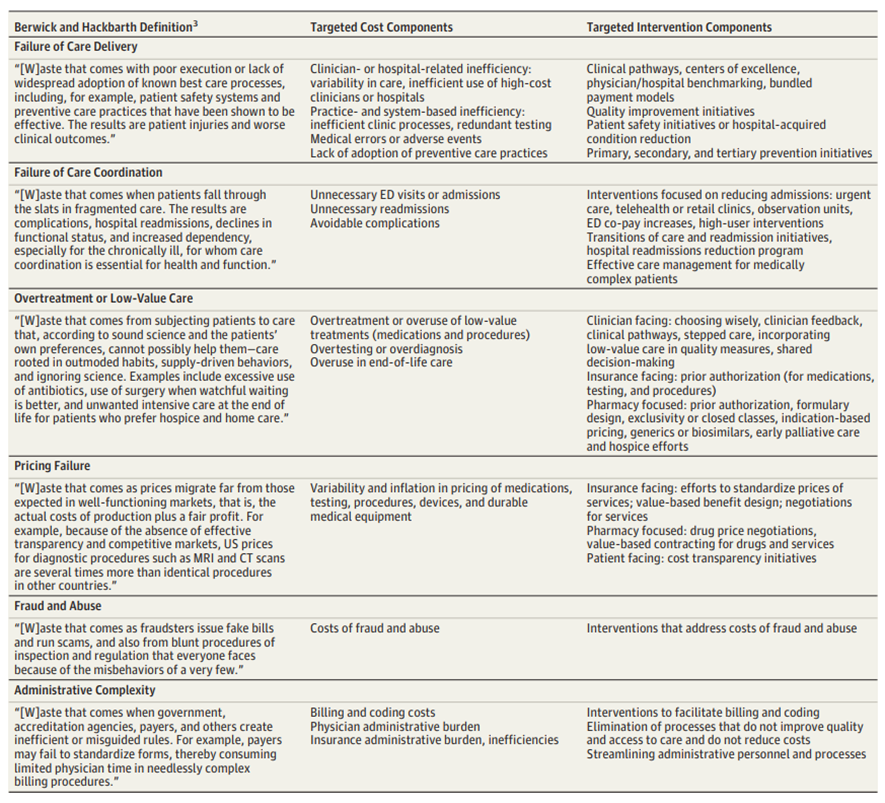

In 2010 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) attempted to estimate the amount of waste in US health care spending and proposed 6 categories of potential sources of waste (Table 1).[2]

Table 1. Six Waste Domains With Cost and Intervention Components

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ED, emergency department; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

In an updated analysis published in 2012, Berwick and Hackbarth[3] reported that approximately 34% of US health care spending in 2011 (according to the authors’ midrange estimates) could be categorized as waste.

Since then, there has been additional focus on the sources of excess spending identified by Berwick and Hackbarth, such as the cost of drugs in the United States[4] [5] [6] [7] [8] and administrative complexity.[9] [10] [11]

Also, in the intervening years since the previously published estimates of waste in health care, a burgeoning body of research on low-value health care services has emerged.[12] [13] [14]

In addition, initiatives to help control health care spending, including both payment reform (eg, accountable care organizations, bundled payments, and value-based payment arrangements with primary care physicians) and delivery reform (improved care coordination, patient-centered medical homes, and the Partnership for Patients initiative) have evolved since previous estimates of wasteful spending.

However, despite efforts to reduce various forms of overspending and initiatives to replace volume-based reimbursement with value-based reimbursement, it is likely that substantial waste in US health care spending remains; elimination of that waste represents an opportunity to help reduce the continual increases in health care expenditures.

This Special Communication provides an update to the IOM and the Berwick-Hackbarth reviews of the estimated levels of waste in the US health care system, using evidence from the intervening 7 years to improve understanding of the current sources of waste in health care spending.

A unique contribution of this update is a review of the ability of the health care system to reduce waste, using recently reported estimates of potential savings from interventions that address each domain of waste.

This added context is essential to help guide system-based reform to reduce waste in the most efficient and effective manner.

Methods

See the original publication!

Results

The review yielded 71 estimates from 54 unique peer-reviewed publications, government-based reports, and reports from the “gray” literature (eTables 2–7 in the Supplement).

The number of cost-plus-savings estimates identified for each of the 6 domains was as follows: failure of care delivery (21), failure of care coordination (11), overtreatment or low-value care (18), pricing failure (9), fraud and abuse (10), and administrative complexity (2).

Failure of Care Delivery

For the “failure of care delivery” domain, 10 articles[22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] addressed costs of waste (Table 2) and 11 articles[32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] addressed potential savings from interventions (Table 3) (2 articles were used for both costs and savings).

Table 2. Cost Estimates by Waste Domain

Cost studies were classified into 3 subcategories: hospital-acquired conditions and adverse events, clinician-related inefficiencies, and lack of adoption of preventive care practices. (The identified examples of clinician-related inefficiencies included unnecessary costs resulting from variation in specialty payments despite the existence of clinical guidelines or in spite of a lack of association between higher intensity practices and outcomes.)

The estimated annual cost of waste from these 3 components ranged from $102.4 billion to $165.7 billion.

Articles that assessed savings from interventions that address this domain were categorized into the following 6 categories: initiatives targeting the reduction of adverse hospital events and hospital-acquired infections; programs to increase physician efficiency, bundled payment models to reduce unnecessary variability in care, and prevention initiatives; integrated physical and behavioral health programs; Partnership for Patients initiative, a CMS-funded activity that engaged a large proportion of the nation’s hospitals and encouraged a wide array of improvement activities; standardized pathways in bundled payment models; and prevention initiatives to address diabetes, obesity, smoking, and cancer.

The estimated potential annual savings ranged from $44.4 billion to $97.3 billion for these interventions, based on extrapolating the most generalizable results to the entire US population.

Table 3. Estimates of Savings From Interventions That Address Waste

Failure of Care Coordination

The 4 studies[43] [44] [45] [46] that assessed costs from failure of care coordination were classified into 2 subcategories (Table 2): unnecessary admissions or avoidable complications and readmissions.

The estimated annual cost of waste from these 2 components ranged from $27.2 billion to $78.2 billion. The 7 studies[47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] [53] that focused on intervention savings were classified into 5 categories (Table 3): emergency department–based strategies (includes video consultations and shift to primary care and retail clinics), care coordination within accountable care organizations (ACOs), health information exchanges, transitional care programs (focused on hospital-to-home transitions), and effective care management for medically complex patients. The estimated total savings from these care coordination interventions ranged from $29.6 billion to $38.2 billion.

Overtreatment or Low-Value Care

The 9 articles (11 estimates)[54] [55] [56] [57] [58] [59] [60] [61] [62] that addressed costs of waste from overtreatment or low-value care were classified into the following categories (Table 2): low-value medication use (branded vs generics or biosimilars and antibiotic resistance costs); low-value screening, testing, procedures; and overuse of end-of-life care.

The estimated total cost of waste from overtreatment or low-value care ranged from $75.7 billion to $101.2 billion. The 6 articles (7 estimates)[63] [64] [65] [66] [67] [68] on savings from interventions that address overtreatment or low-value care were divided into the following categories (Table 3):

optimizing medication use, prior authorization, ACO interventions that address overtreatment or low-value care, use of shared decision-making to reduce unnecessary procedures, and savings from expanding hospice access (2 articles were used both for costs and for savings). The estimated amount that could be saved annually if these successful interventions could be scaled nationally ranged from $12.8 billion to $28.6 billion.

Pricing Failure

The 4 articles[69] [70] [71] [72] that assessed costs of pricing failure were classified into the following categories (Table 2): medication pricing; payer-based health services pricing; and laboratory-based and ambulatory pricing.

The estimated cost of waste from pricing failure ranged from $230.7 billion to $240.5 billion. The 5 articles[73] [74] [75] [76] [77] that assessed savings from interventions that address pricing failure (3 articles were used both for costs and for savings) were categorized as drug pricing interventions, payer-focused interventions (including all-payer models), and pricing transparency strategies for laboratory orders and office visits (Table 3).

The estimated total savings from interventions that address pricing failure ranged from $81.4 billion to $91.2 billion.

Fraud and Abuse

The 3articles[78] [79] [80] that addressed costs of waste from fraud and abuse (Table 2) focused on the Medicare population, and total estimated costs ranged from $58.5 billion to $83.9 billion.

Four additional articles[81] [82] [83] [84] (5 estimates; 2 articles were used both for costs and for savings) that assessed savings from government-based (Department of Justice, Office of the Inspector General, and CMS) interventions (Table 3) were categorized into those that addressed recovery from convictions and fraud settlements and those that focused on legislative, administrative, and integrity strategies.

The estimated annual savings from these interventions ranged from $22.8 billion to $30.8 billion.

Administrative Complexity

Two articles[85] [86] addressed cost of waste from administrative complexity (Table 2), and no articles were identified that addressed savings from interventions. The estimated total annual cost of waste in this category was $265.6 billion.

Discussion

This review of the current literature of the cost of waste in the US health care system and evidence about projected savings from interventions that reduce waste suggests that the estimated total costs of waste and potential savings from interventions that address waste are as high as $760 billion to $935 billion and $191 billion to $286 billion, respectively.

These estimates represent approximately 25% of total health care expenditures in the United States, which have been projected to be $3.82 trillion for 2019.[87]

These estimates are lower than the estimates provided by the IOM report (31%)[88] and by Berwick and Hackbarth[89] (34%), using authors’ mid-range cost estimate), although those estimates included savings from administrative costs.

However, the best available evidence about the cost savings of interventions targeting waste, when scaled nationally, account for only approximately 25% of total wasteful spending.

These findings highlight the challenges inherent in rapidly changing the course of a health system that accounts for more than $3.8 trillion in annual spending, 17.8% of the nation’s GDP.[90]

The administrative complexity category was associated with the greatest contribution to waste, yet there were no generalizable studies that had targeted administrative complexity as a source for waste reduction.

Some of that complexity results from fragmentation in the health care system.

Recent proposals by CMS and the Office of the National Coordinator of Health Information Technology to foster data interoperability and government initiatives such as Blue Button 2.0 will hopefully alleviate some burden as information flows more freely and billing and authorization processes become more automated.

The greater opportunity to reduce waste in this category should result from enhanced payer collaboration with health systems and clinicians in the form of value-based payment models.

In value-based models, in particular those in which clinicians take on financial risk for the total cost of care of the populations they serve, many of the administrative tools used by payers to reduce waste (such as prior authorization) can be discontinued or delegated to the clinicians, reducing complexity for clinicians and aligning incentives for them to reduce waste and improve value in their clinical decision-making.

As more clinicians transition into value-based payment arrangements with financial risk, administrative burden and oversight could be reduced for all health care constituencies, including payers, hospitals, and physician practices; adoption of global prepayment mechanisms for patients and populations rather than fee-for-service payments would be expected to accelerate reductions in administrative complexity.

Moreover, there is a need for better methods of assessing strategies to reduce administrative complexity while maintaining quality and without increasing spending.

Presumably, all health systems, clinician practices, and payers have efforts underway to simplify processes and explore digital solutions to reduce administrative complexity.

The science describing the success of these interventions is limited and more evidence is needed to quantify the waste in this category that could be reduced and the resulting savings.

The category that represents the second largest contributor to waste in the United States is pricing failure.

In many ways, the evolution to value-based care would be expected to produce the least savings in this category since pharmaceutical pricing represents a major component of this waste domain and would not be affected by new approaches to care delivery and reimbursement.

New high-cost specialty drugs, which will soon exceed 50% of pharmaceutical spending, are raising new questions about how to maintain affordability.[91]

Over the next decade, CMS projects that prescription drug spending will be the fastest-growing cause of rising health care expenditures.[92]

This topic has thus received considerable attention from policy makers, and numerous proposals are currently under consideration.

These proposals advocate enhanced market competition, reimportation of drugs from less expensive nations, leveraging pricing negotiated by other nations, and greater transparency of pricing and return of rebates to patients at point of sale. Some efforts are under way to address the price of care delivery.

Numerous policies are under consideration to improve cost transparency for hospital services and to eliminate out-of-network surprise billing, which can lead to substantial pricing increases for those affected.

Importantly, these pricing-related sources of waste have arisen in the existing competitive US health care marketplace, and likely result, at least in part, from the complex regulatory framework that governs the health care system.

Policy interventions are needed to drive meaningful reductions in waste in this domain. Additionally, in the dynamic health care marketplace, where profit motivated firms will respond to any new policy with strategies to protect their margins, no single policy is likely to suffice; a coordinated policy effort is likely needed to create long-standing change that will meaningfully reduce waste resulting from pricing failure.

In the failure of care delivery, failure of care coordination, and overtreatment or low-value care categories, the data from this review suggest that more than $200 billion in waste remains in the US health care system.

There is compelling empirical evidence in all 3 categories that interventions can produce meaningful savings and may reduce waste by as much as half.

Many of these interventions have arisen in settings where payers are collaborating with clinicians and health systems, either to align payment models with value or to support delivery reform to enhance care coordination, safety, and value.

Some experts have noted that the move to value-based care arrangements has produced less savings than had been anticipated and that care transformation has been slower than they had hoped for.

However, in the setting of broader adoption of value-based care, there is growing evidence to suggest that some interventions are improving care and reducing downstream costs.

While it is not realistic to expect to eliminate all waste in these categories, the evidence base to guide future interventions is growing.

As value-based care continues to evolve, there is reason to believe such interventions can be coordinated and scaled to produce better care at lower cost for all US residents.

It is notable that, as there is greater adoption of value-based care models in the United States, there is increasing interdependency between these waste categories.

Administrative complexity is the greatest source of waste in the United States today and can be a result of payers’ efforts to reduce waste by reducing overtreatment and low value care.

In value-based arrangements, improvements could be expected to reduce waste in both categories.

Similarly, payer health system collaboration to improve care coordination and transitions in care could be expected to improve safety and reduce failures in care delivery.

Additionally, greater alignment between payers and clinicians should assist in efforts to reduce fraud and abuse, while simultaneously reducing low-value care.

Limitations

See the original publication!

Conclusions

In this review based on 6 previously identified domains of health care waste, the estimated cost of waste in the US health care system ranged from $760 billion to $935 billion, accounting for approximately 25% of total health care spending, …

… and the projected potential savings from interventions that reduce waste, excluding savings from administrative complexity, ranged from $191 billion to $286 billion, …

… representing a potential 25% reduction in the total cost of waste.

Implementation of effective measures to eliminate waste represents an opportunity to reduce the continued increases in US health care expenditures.

References

See the original publication

About the authors

William H. Shrank, MD, MSHS 1;

Teresa L. Rogstad, MPH 1;

Natasha Parekh, MD, MS 2

Author Affiliations

- 1 Humana Inc, Louisville, Kentucky

- 2 Division of General Internal Medicine,

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Originally published at https://jamanetwork.com