The Washington Post

By the Editorial Board

May 8, 2022

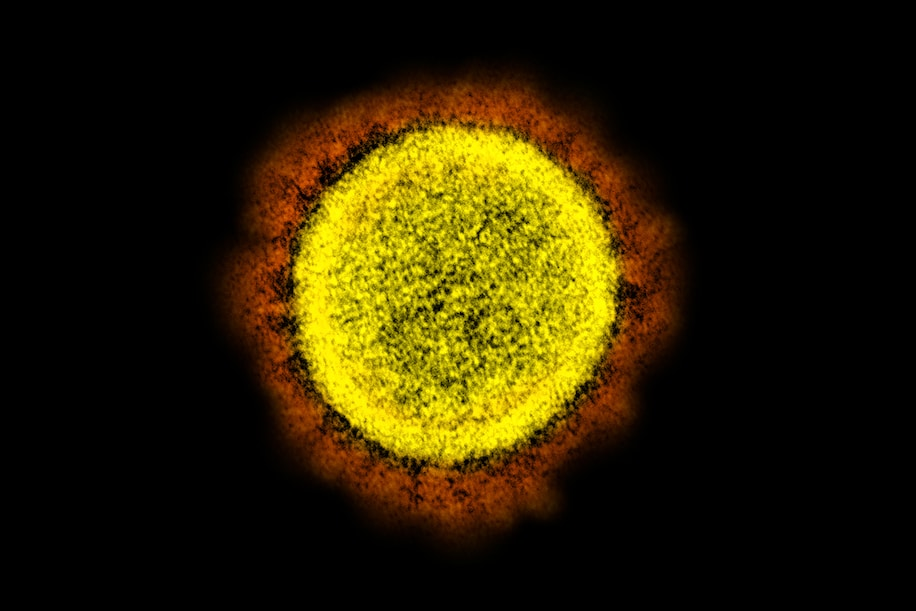

A 2020 electron microscope image of a novel coronavirus particle isolated from a patient, in a laboratory in Fort Detrick, Md. (AP)

A 2020 electron microscope image of a novel coronavirus particle isolated from a patient, in a laboratory in Fort Detrick, Md. (AP)

Every coronavirus particle carries a kind of Mother Nature bar code inside: the genome, or genetic blueprint. With advances in bioinformatics, scientists can use genetic sequencing to read the bar code, identify the variant, spot mutations and chart possible spread among people. There’s a growing consensus that tracking this with viral genomic surveillance can provide critical early warning of public health emergencies — but only if resources and commitment are marshaled.

“Surveillance” in public health terminology means a system to monitor a population for threats such as viruses and bacteria. Think of it as a fire alarm for health. Already, the nation relies upon early-warning systems to watch for hurricanes and tornadoes, for example. The U.S. military maintains an elaborate system of radars and satellites to watch for ballistic missile threats. Early warning is critical to intelligence, news and markets. We need a global and national early-warning system for disease. It doesn’t exist now, except in fragments.

Remember when pandemonium broke out in New York City hospitals, personal protective gear ran out, ventilators were short and patients piled up in waiting ambulances on the streets? James Lu, chief executive officer and co-founder of Helix, a sequencing and population genomics firm, told us that even a few weeks of extra warning time would help avert such a scenario. “In a fast moving pandemic, three to four weeks of knowledge or prediction ahead of time allows you to prepare supply chains, to prepare resilience and put countermeasures in place,” he said.

The idea is catching on. Philanthropist Bill Gates has just published a book, “How to Prevent the Next Pandemic,” calling for a rapid response team prepared to stop a pandemic in 100 days. The World Health Organization has published a 10-year global genomic surveillance strategy, noting that 1 in 3 countries lack such capability. The White House has promised to redouble efforts to improve data collection, sequencing and surveillance activity to “immediately identify and detect new and emerging” viral variants. The Rockefeller Foundation has published a plan for the “urgent amplification of national genomic surveillance.” The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, created to study the world’s reaction, called for “a new global system for surveillance, based on full transparency by all parties, using state-of-the-art digital tools to connect information centers around the world.”

Many hurdles stand in the way of such a goal. It will require a level of international cooperation and information-sharing that, as the pandemic demonstrated, does not now exist on many public health matters. It also will demand more of technology and political will. In the United States, building a truly national, rapid-response early-warning system will require, as Dr. Lu points out, modernizing the system of collecting data from disparate sources, sharing it smoothly through data pipelines and drawing conclusions from it. In particular, genomics should be linked with clinical outcomes, which would point to whether a variant causes more severe illness.

A genomic early-warning system is more vision than reality now, but it is a vision worth striving for.

Originally published at https://www.washingtonpost.com on May 8, 2022.

The Post’s View | About the Editorial Board

Editorials represent the views of The Washington Post as an institution, as determined through debate among members of the Editorial Board, based in the Opinions section and separate from the newsroom.

Members of the Editorial Board and areas of focus: Deputy Editorial Page Editor Karen Tumulty; Deputy Editorial Page Editor Ruth Marcus; Associate Editorial Page Editor Jo-Ann Armao (education, D.C. affairs); Jonathan Capehart (national politics); Lee Hockstader (immigration; issues affecting Virginia and Maryland); David E. Hoffman (global public health); Charles Lane (foreign affairs, national security, international economics); Heather Long (economics); Molly Roberts (technology and society);

and Stephen Stromberg (elections, the White House, Congress, legal affairs, energy, the environment, health care).