This is a republication of the paper below, with the title above, highlighting the message in question.

How low can we go? Strategies and recommendations to combat the iodinated contrast shortage

Emergency Radiology

Liesl S. Eibschutz & Ali Gholamrezanezhad

25 July 2022

Executive Summary by:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

health transformation . institute

low value care reduction unit

July 28, 2022, (modern healthcare image)

Abstract

- After GE Healthcare, one of the major producers of iodinated contrast dye, was forced to close their Shanghai factory due to a recent COVID-19 outbreak, iodinated contrast media shortages have rocked healthcare systems to their core.

- Clinicians nationwide are now caught between the desire to provide patients with optimal care and the need to conserve the minimal remaining supplies of iodinated contrast media.

- While GE Healthcare has reopened their factory and other sources of contrast agents have become available, experts report that levels may not return to normal through June 2022.

- Thankfully and ironically, radiology departments are all too familiar with COVID-19 associated operational disruptions and have been quick to adapt and implement novel protocols to evade this and other crises.

- Overall, this shortage emphasizes the importance of interprofessional communication, adaptation, and preparation for future emergent situations as this is not the first iodinated contrast material shortage and it likely would not be the last.

Conclusion

- Over the past few years, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world’s largest companies to rethink the supply chain and adapt to the everchanging barriers that arise.

- As situations like these will undoubtedly recur in the future, it is imperative that we prepare now and perhaps consider increasing the number of domestic factories that could manufacture ICM.

- Ultimately, further research should be obtained on the imaging studies that have been conducted over the course of the ICM shortage, in order to determine if these policies surrounding contrast use affected patient management or compromised patient outcome.

- This shortage emphasizes the importance of avoiding contrast overuse and unnecessary applications as this is likely not the last time we will encounter iodinated contrast media shortages.

- Also, research should be conducted to study the effects of the contrast shortage on the clinical outcome of patients in diverse settings.

Key messages:

- This shortage emphasizes the importance of avoiding contrast overuse and unnecessary applications as this is likely not the last time we will encounter iodinated contrast media shortages

- By identifying the exact situations in which contrast should be utilized, we can optimize patient care and minimize controversy surrounding this issue.

- In order to avoid contrast material waste and achieve minimal effective doses, many authors urge hospitals to begin weight-based dosing for CT in available aliquots/vial sizes [ 1].

- For certain procedures such as angiographic studies, there are further steps available to decrease the amount of contrast utilized.

- For instance, biplane angiography allows two images to be acquired for each contrast injection.

- Other ways to decrease contrast dose include using smaller catheters for diagnostic angiography, utilizing reduced CT tube voltages, and removing contrast prior to medication delivery or catheter removal [ 2].

- Other researchers note the utility of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guided procedures when possible. Mariani et al. were able to reduce contrast volume by over 50% when utilizing IVUS-based contrast reduction techniques [ 3].

- It would be remiss to ignore the multitude of disadvantages inherent in conducting imaging studies without iodinated contrast media, particularly in the emergency radiology setting.

- Yet for a significant group of patients, the decreased diagnostic accuracy of non-contrast CT may have no effect on patient outcome.

- For situations in which contrast media is completely unavailable, various other imaging modalities can be utilized in its place.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

Introduction

While the major wave of acute coronavirus (COVID-19) infections has subsided, the effects of this deadly virus continue to reverberate across the globe.

The latest COVID-19-related conundrum pertains to iodinated contrast media (ICM), which is commonly utilized in a variety of imaging techniques such as contrast-enhanced CT (CECT), conventional angiography and venography, CT angiography, and fluoroscopic examinations.

GE Healthcare, the major producer of Omnipaque™ (iohexol) ICM, primarily operates out of factories in Shanghai, China. However, a recent COVID-19 lockdown in Shanghai has left hospitals across the nation scrambling to obtain iodinated contrast medium.

Unfortunately, other companies that manufacture ICM have been unable to rapidly scale up production of these agents to meet current demand.

While the Shanghai factory has recently reopened to 50% production levels and other sources of contrast agents have become available, experts report that this shortage may persist through June 2022.

This is not the first shortage, and it would not be the last, thus it is imperative that we identify alternative measures to decrease the effects of this supply shortage and provide recommendations for how hospitals and clinicians can adapt in the absence of iodinated contrast media.

In many hospitals across the USA, the use of contrast-enhanced CT has dropped by up to 95%, forcing clinicians to make critical decisions on which patients need ICM the most.

Currently, clinicians have been working on a case-by-case basis, considering factors such as hemodynamic status, presenting symptoms, and location of injury.

In many hospitals across the USA, the use of contrast-enhanced CT has dropped by up to 95%, forcing clinicians to make critical decisions on which patients need ICM the most.

In order to function on a case-by-case basis, guidelines should be developed that highlight the situations in which procedural IV contrast is appropriate for use.

In conjunction with statements from the American College of Radiology (ACR), current recommendations include:

- the study is needed to change management,

- there is no alternative imaging technique that can be used with similar accuracy,

- an acute condition requiring emergency/inpatient care for which delays in contrast administration would increase the risk of morbidity/mortality,

- or an outpatient condition that will result in a detrimental morbidity or mortality if the imaging study is delayed by > 6 weeks.

Some hospitals have been operating on an “acute risk of life and limb” basis, with CECT only for severe trauma or acute abdomens, CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) for hemorrhage or severe hemodynamic compromise, and conventional angiography for cardiac or neurologic compromise, limb ischemia, trauma, or hemorrhage.

By identifying the exact situations in which contrast should be utilized, we can optimize patient care and minimize controversy surrounding this issue.

By identifying the exact situations in which contrast should be utilized, we can optimize patient care and minimize controversy surrounding this issue.

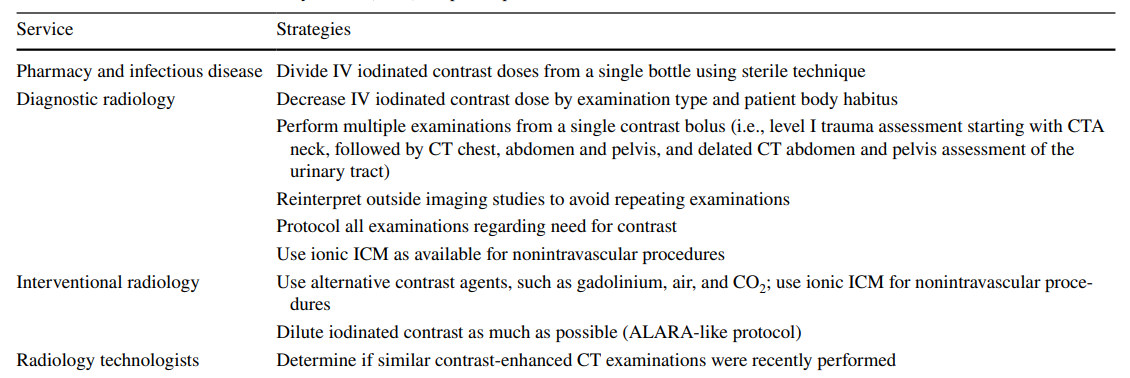

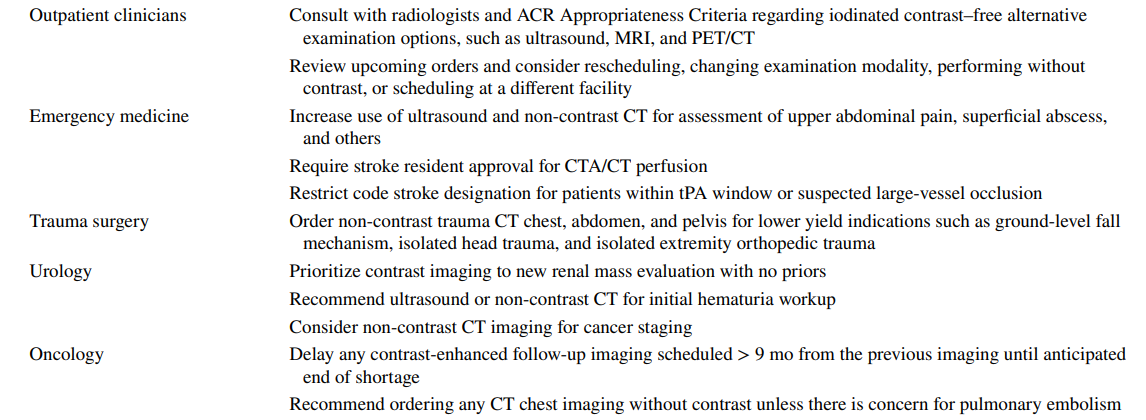

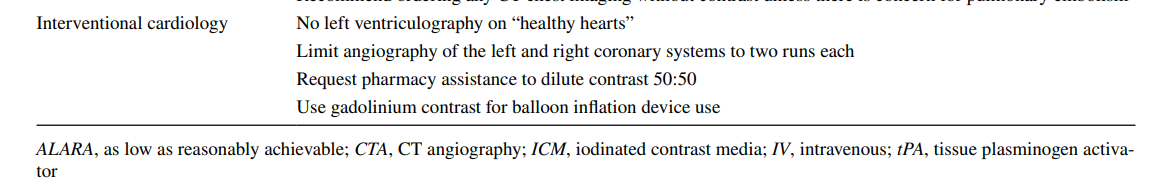

Further mitigation strategies are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 Contrast shortage mitigation strategies by service.

Table reproduced with permission from Allen, L. M., Shechtel, J., Frederick-Dyer, K., Davis, L. T., Stokes, L. S., Savoie, B., Pruthi, S., Henry, C., Allen, S., Frazier, S. R., & Omary, R. A. (2022). Rapid response to the acute iodinated contrast shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic: single-institution experience. Journal of the American College of Radiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2022.05.005

In order to avoid contrast material waste and achieve minimal effective doses, many authors urge hospitals to begin weight-based dosing for CT in available aliquots/vial sizes [ 1].

For certain procedures such as angiographic studies, there are further steps available to decrease the amount of contrast utilized.

- For instance, biplane angiography allows two images to be acquired for each contrast injection.

- Other ways to decrease contrast dose include using smaller catheters for diagnostic angiography, utilizing reduced CT tube voltages, and removing contrast prior to medication delivery or catheter removal [ 2].

- Other researchers note the utility of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guided procedures when possible. Mariani et al. were able to reduce contrast volume by over 50% when utilizing IVUS-based contrast reduction techniques [ 3].

The value of dual energy or spectral CT

In CT imaging, the utilization of dual-energy CT when available can lower the amount of contrast required as well.

While the specific X-ray beam energies (keV) often reach 70 keV to produce higher contrast resolution and less noise, noise-optimizing image reconstruction algorithms in dual-energy CT can lower the keV level to 40–50 [ 4].

This in turn decreases the amount of ICM necessary for one procedure. Other authors have indicated that further optimization of ICM dose is possible if flow rate and contrast media volume are tailored to the specific monoenergetic level with dual-energy acquisitions and tailored to the automatically selected tube potential with single-energy acquisitions [ 5].

In order to ensure ICM is available for critical procedures, the ACR notes that it is crucial to reserve higher concentration (mg iodine/ml) agents for studies requiring optimal vascular visualization, such as multiphase and angiographic studies [ 1].

However, in situations where ICM is not available, various other alternatives can be utilized in its place.

While not often employed, carbon dioxide (CO 2) can be used as contrast media for infradiaphragmatic arteriography and central venography above the diaphragm [ 6]. As CO 2 is less viscous compared to blood, it can detect subtle bleeding and allow visualization of smaller collateral vessels [ 7].

However, there are a variety of limitations associated with CO 2 as a contrast agent, including user difficulty and lack of availability. In addition, the possibility of neurotoxicity limits its use within or near the cerebral circulation [ 8].

Another potential option includes diluting higher osmolality contrast agents so long as the iodine concentration is still sufficient for diagnostic imaging [ 9].

In the ACR Contrast Manual, the authors discuss multiple alternatives to ICM, such as barium-based products as oral ICM, and diatrizoate or iothalamate meglumine for oral, genitourinary, or rectal administration [ 1].

For fluoroscopic imaging, including catheter angiography and intraoperative arthrography, diatrizoate meglumine can be utilized, and some studies have even suggested use of gadolinium contrast as well [ 10].

However, it is imperative to make adjustments for the different keV of gadolinium compared to iodine in this setting.

In addition, the use of gadolinium contrast in X-ray imaging is not recommended by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) unless absolutely necessary [ 10].

Alternative imaging modalities

For situations in which contrast media is completely unavailable, various other imaging modalities can be utilized in its place.

The ACR appropriateness criteria can be a useful guide for clinicians looking to find suitable alternatives and can be stratified by situation.

- For instance, follow-up in cancer patients with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid tumors should involve FDG-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT.

- Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can also be used in place of CT angiography in hemodynamically stable patients with thoracic aorta dissection or abdominal aortic aneurysms [ 10].

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) liver is a suitable alternative for multiphase liver CT in the evaluation of cirrhosis or other focal liver lesions, …

- and contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) can be appropriate for focal liver or cystic pancreatic lesions as well [ 11].

- Brain MRI/MRA protocols can also be adapted and abbreviated for stroke evaluation. However, the lack of widespread MRI availability makes this difficult to adapt large scale.

Interprofessional communication is the key

This shortage emphasizes the importance of interprofessional communication and collaboration between emergency department physicians, ordering clinicians, and radiologists.

In order to effectively combat this shortage, many authors have noted that the most effective first step is establishing awareness of the ICM shortage throughout the hospital system [ 11].

An institution-wide committee should be created comprised of radiologists, institutional leadership, and representatives from departments that highly rely on ICM such as cardiology, vascular surgery, urology, and radiation oncology.

Radiologists should spearhead this committee, as they are ultimately the providers of the limited resource and are highly attune to clinical disruptions due to COVID-19.

This committee should establish plans for contrast conservation, implement new processes and workflows, and provide communication to the institution as a whole [ 12].

In critical cases in which next steps are not clearly defined, this multidisciplinary committee should discuss them and decide the plan together.

In addition, it should be communicated that all non-essential imaging studies that require contrast will be postponed until ICM levels have reached normal levels.

Lastly, this shortage must be communicated clearly to patients to raise awareness that many imaging studies may not be available to them at this time and encourage discussions about the current alternative options available.

No contrast… no problem?

It would be remiss to ignore the multitude of disadvantages inherent in conducting imaging studies without iodinated contrast media, particularly in the emergency radiology setting.

CT is often the imaging modality of choice in patients presenting with acute trauma or an acute abdomen, and it is undeniable that the diagnostic accuracy of CECT is far superior when compared to non-contrast CT.

In patients with severe injuries, many clinicians agree that contrast should be utilized to avoid missing a life-threatening diagnosis.

In addition, when non-contrast exams are non-diagnostic, repeat scans are often required, unnecessarily exposing patients to additional radiation.

Yet for a significant group of patients, the decreased diagnostic accuracy of non-contrast CT may have no effect on patient outcome.

For example, some people claim that trauma-related findings on CECT in a patient who had a negative non-contrast CT may not even change management.

This begs the question whether we have been overusing iodinated contrast media, as in many cases, patient management would remain unchanged even if the diagnosis is only visible on contrast-enhanced CT.

Ultimately, long-term studies are vital to parse out whether the absence of iodinated contrast media greatly affected patient outcomes or if we have been overdependent on ICM unnecessarily.

Ultimately, long-term studies are vital to parse out whether the absence of iodinated contrast media greatly affected patient outcomes or if we have been overdependent on ICM unnecessarily.

Conclusion

Over the past few years, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world’s largest companies to rethink the supply chain and adapt to the everchanging barriers that arise. As situations like these will undoubtedly recur in the future, it is imperative that we prepare now and perhaps consider increasing the number of domestic factories that could manufacture ICM. Ultimately, further research should be obtained on the imaging studies that have been conducted over the course of the ICM shortage, in order to determine if these policies surrounding contrast use affected patient management or compromised patient outcome. This shortage emphasizes the importance of avoiding contrast overuse and unnecessary applications as this is likely not the last time we will encounter iodinated contrast media shortages. Also, research should be conducted to study the effects of the contrast shortage on the clinical outcome of patients in diverse settings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Liesl S. Eibschutz 1;

Ali Gholamrezanezhad 1

Department of Radiology,

Keck School of Medicine,

University of Southern California,

1500 San Pablo Street, Los Angeles, CA 90033, USA

Cite this article

Eibschutz, L.S., Gholamrezanezhad, A. How low can we go? Strategies and recommendations to combat the iodinated contrast shortage. Emerg Radiol (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-022-02077-7

Originally published at https://link.springer.com on July 25, 2022.