Site editor:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Health Institute — for continuous health transformation

October 4, 2022

Economic loss attributable to cigarette smoking in the USA: an economic modelling study

The Lancet — Public Health

Nigar Nargis, PhD

Prof A K M Ghulam Hussain, PhD

Samuel Asare, PhD

Zheng Xue, MSPH

Anuja Majmundar, PhD

Priti Bandi, PhD

Farhad Islami, PhD

K Robin Yabroff, PhD

Ahmedin Jemal, PhD

OCTOBER 01, 2022

SUMMARY

Background

- Despite large geographical disparities in the prevalence of cigarette smoking across the USA, there is a paucity of state-level estimates of economic loss attributable to smoking to inform tobacco control policies at the national and state levels.

- We aimed to estimate the state-level economic loss attributable to cigarette smoking in the USA.

Methods

- In this economic modelling study, we used a dynamic macroeconomic model of personal income per capita at the state level.

- Based on publicly available data on state-level income, its determinants, and smoking status for 2011–20, we first estimated the elasticity of personal income per capita with respect to the prevalence of non-smoking adults (aged ≥18 years) in the USA using a mixed-effects, generalised linear, dynamic panel data model.

- We used the estimated elasticity to measure the state-specific, annual, avoidable economic loss attributable to cigarette smoking in 2020 under the counterfactual 5% prevalence of cigarette smoking.

- We then estimated the state-specific cumulative economic loss attributable to cigarette smoking in 2020 using the coefficient of lagged income in the dynamic model.

- National estimates on economic loss attributable to cigarette smoking were obtained by summing state-specific estimates.

Findings

- In the mixed-effects model, the elasticity of personal income per capita with respect to the prevalence of non-smoking adults was 0·143 (p=0·063).

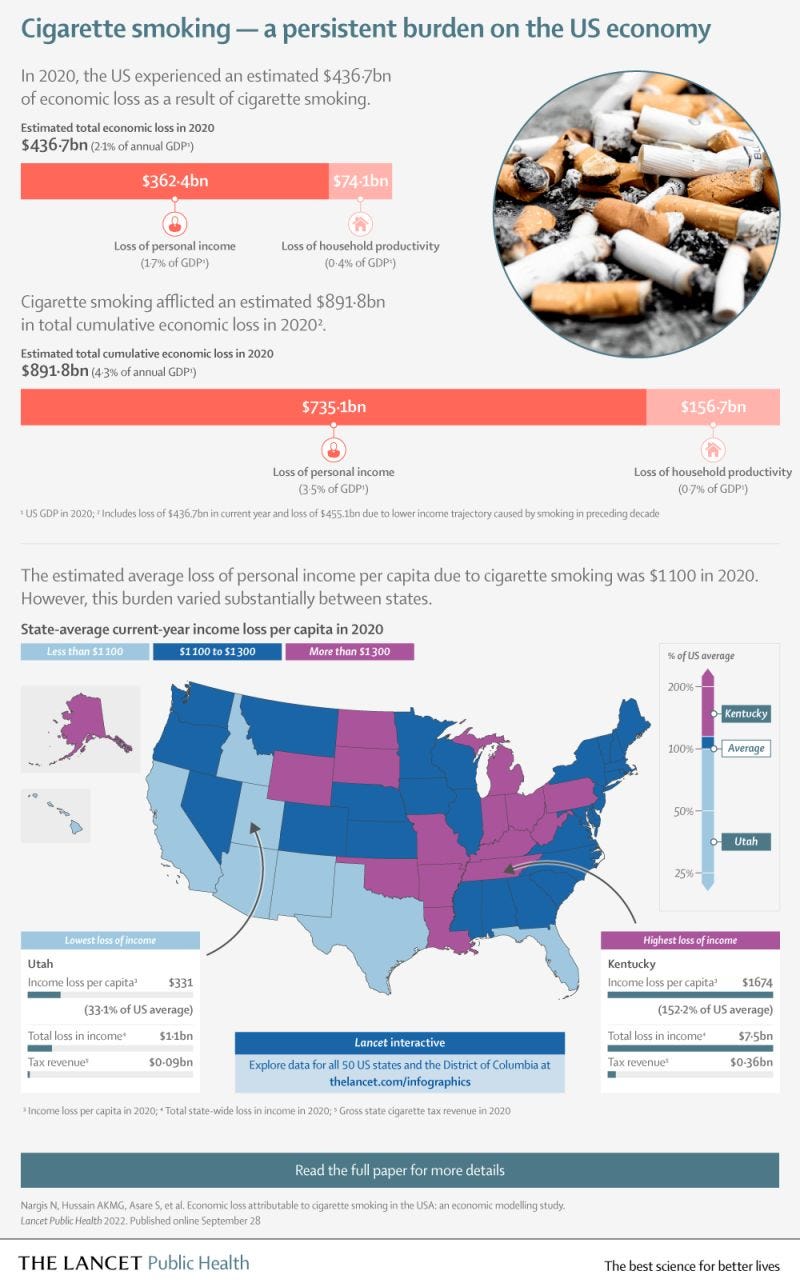

- The estimated annual income loss per capita in 2020 ranged from US$331 in Utah to $1674 in Kentucky.

- The state mean population-weighted loss per capita was $1100.

- The annual combined loss of income and unpaid household production at the national level was $436·7 billion (equivalent to 2·1% of US gross domestic product [GDP] in 2020).

- The cumulative loss of income and unpaid household production was $864·5 billion (equivalent to 4·3% of US GDP in 2020).

- This substantial net loss to the economy can be mitigated with coordinated and comprehensive evidence-based tobacco control measures, which promote cessation and prevent initiation of tobacco use.

- In 2014, there were an estimated 461 295 annual hospitalisations for cancer cases attributable to tobacco use at the cost of $8·2 billion, accounting for 45% of hospitalisation costs across the USA.

Interpretation

- Smoking causes substantial economic loss in the USA.

- Tobacco control efforts that lower the prevalence of smoking equitably can contribute considerably to improved macroeconomic performance in the short and long term by reducing health expenditures and avoiding productivity losses.

Tobacco control efforts that lower the prevalence of smoking equitably can contribute considerably to improved macroeconomic performance in the short and long term by reducing health expenditures and avoiding productivity losses.

Implications of all the available evidence

- Smoking causes substantial economic loss in the USA.

- The US Department of Health and Human Services set the

Healthy People 2030 goal to reach a 5% prevalence of cigarette

smoking among the adult population (aged ≥18 years) by 2030,

from the baseline prevalence of 14% in 2018.

- The achievement of this goal through tobacco control efforts at the national,

state, and local levels would considerably reduce the economic

loss attributable to smoking.

- Additionally, reaching this target would contribute to improved macroeconomic performance by diverting scarce resources away from treating smokingattributable illnesses towards increasing market and household productivity and income.

Infographic:

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION [excerpt]

Introduction

In the USA, tobacco smoking causes illnesses among more than 16 million adults and 527 736 premature deaths each year, accounting for 17·9% of all deaths annually.,

Most of the tangible costs attributable to tobacco smoking are evident in two areas:

- health expenditures to treat illnesses and

- productivity loss due to morbidity and premature mortality.

Health-care expenses or funding for tobacco control activities divert resources away from physical and human capital accumulation, as well as the research and development needed for technological progress and productivity growth.

Furthermore, illnesses and deaths attributable to tobacco smoking reduce the participation and employability of the labour force.

Previous studies in the USA based on the cost-of-illness approach showed that use of tobacco products and exposure to second-hand smoke were associated with excess health-care use and expenditure (including out-of-pocket catastrophic health-care expenses, medical expenses covered by private and public health insurance, and government spending on health-care infrastructure), and loss of market and household productivity.

Only one study has included both health-care costs and productivity loss attributable to tobacco smoking to measure total economic cost.

However, these studies estimated health-care expenses and productivity losses attributable to tobacco smoking as independent components without consideration of the fact that resources used for the treatment of tobacco-attributable diseases and tobacco control can otherwise be used for investments in physical and human capital, as well as research and development, which can in turn reinforce productivity and economic growth.

Furthermore, estimates on the economic burden of tobacco smoking in the USA at the state level are scarce ( appendix pp 2–11).

State-level data are necessary to inform tobacco control policies, given that most efforts are implemented at the state and local levels across the USA.

We aimed to fill this data gap by providing a combined estimate of economic loss attributable to cigarette smoking in the USA, covering health-care spending, productivity loss, and the costs emerging from their interdependencies at the state level and national level, based on a dynamic macroeconomic model of state-level personal income per capita.

Other sections:

See the original publication

Discussion

Using a mixed-effects generalised linear model at the state level, this economic modelling study estimated that the elasticity of personal income per capita, with respect to prevalence of non-smokers, was 0·143, indicating that a reduction in smoking has the potential to generate considerable growth in income.

At the macroeconomic level, total annual economic loss attributable to smoking in 2020 was US$436·7 billion, equivalent to 2·1% of US GDP that year. We estimated that the cumulative economic loss in 2020 was $891·8 billion, equivalent to 4·3% of US GDP, which is greater than the previous estimate for the USA (3·2%). 11

The mixed-effects estimate of the elasticity of personal income per capita with respect to smoking status was somewhat lower than the random-effects estimate.

This difference is most plausibly due to the ability of the mixed-effects model to nest variability both within and between states in regressors.

Additionally, the estimate from this current study contrasts sharply with the $94·2 billion annual market value of cigarette sales in the USA, which is accrued to the tobacco industry as profits, to employees of the tobacco industry as wages and salaries, and to the governments as tax revenue and user fees that might become available for the health budget (including for tobacco control funding).

These findings indicate that the economic loss from cigarette smoking far outweighs the value generated by the cigarette market for the US economy.

This substantial net loss to the economy can be mitigated with coordinated and comprehensive evidence-based tobacco control measures, which promote cessation and prevent initiation of tobacco use.

These findings indicate that the economic loss from cigarette smoking far outweighs the value generated by the cigarette market for the US economy.

This substantial net loss to the economy can be mitigated with coordinated and comprehensive evidence-based tobacco control measures, which promote cessation and prevent initiation of tobacco use.

By taking into account the full value of lost productivity, these results suggest that the economic loss at the national level far exceeds previous estimates.

For instance, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Smoking-Attributable Mortality, Morbidity, and Economic Costs system, cigarette smoking and exposure to second-hand smoke caused a total of $96·8 billion in annual productivity loss in the USA between 2000 and 2004 (equivalent to 0·8% of US GDP in 2004).

The US Surgeon General’s report in 2014 estimated that, from 2005 to 2009, average annual productivity loss at the national level was $150·7 billion due to smoking and $5·7 billion due to exposure to second-hand smoke.

However, these estimates do not reflect the full value of lost productivity because they did not account for lost productivity due to morbidity, which has been estimated to be $184·9 billion for the year 2018.

Additionally, health expenditures related to cigarette smoking accounted for 11·7% (>$225 billion) of total annual health-care spending in the USA in 2014, compared with previous estimates of 7–9% (ie, $132·5 billion in 2009, $170·6 billion in 2010, and $175·9 in 2012).,

In 2014, there were an estimated 461 295 annual hospitalisations for cancer cases attributable to tobacco use at the cost of $8·2 billion, accounting for 45% of hospitalisation costs across the USA.

Tobacco control efforts should take into account the higher estimates of this study when planning and allocating resources.

The estimates of economic loss attributable to smoking in this study improve on existing estimates in several ways.

First, the human capital approach used in previous studies focuses on worker productivity and does not consider the reduction in employment probability or in the number of adults at working age, which is driven by morbidity and mortality related to tobacco. In turn, these effects on the labour market transmit into the substitution of labour and capital, and the accumulation of physical and human capital over time, affecting the aggregate-level output and income. Measuring personal income per capita instead incorporates all of these outcomes ( appendix pp 13–14).

Second, the human capital approach tends to overestimate the economic burden of premature death by focusing on the earning loss of the deceased worker, despite how the individual can be replaced with excess supply of equally productive workers in the economy. The aggregate output is not affected under this circumstance, except for the frictional cost to search for and hire a replacement worker by the employer.

By contrast, a loss of output is observed in the economy when the deceased worker is irreplaceable with a living person. The reduced form estimate of the elasticity of income per capita with respect to smoking status used in this study reflects the net effect of these opposite changes at the aggregate level, with other factors remaining the same.

Third, the measurement of excess health expenditure or productivity loss in previous studies focused on annual loss. However, deaths and diseases related to smoking in one period not only affect income in that period, but some of that effect is also propagated into future periods through income in previous periods. Therefore, the full impact of smoking should capture the cumulative effects over time. By applying a dynamic macroeconomic framework in capturing the future effects of smoking on income loss, this study provides a measure of the long-term economic burden of smoking.

Finally, this study is the first to derive state-level estimates of the economic costs of morbidity and mortality attributable to smoking in the USA, which highlights the spatial disparity in smoking and could inform policy interventions for tobacco control at the state level, particularly in US states with a disproportionately high burden of tobacco consumption and in those that grow tobacco. The large economic losses attributable to smoking, estimated at both state and national levels in this study, provide further impetus for the ratification of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control by the USA.

Nevertheless, the utility of this approach goes far beyond invoking policy implications for tobacco control. The measures of personal income per capita and smoking status relative to average state levels used in this study identify the role that spatial disparity in smoking behaviour plays in the persistence of disparities in state income per capita. US states that have fallen behind the rest of the nation in economic growth and welfare can act on factors, such as tobacco control, that have the potential to accelerate growth and income convergence. The state-level estimates of economic loss attributable to smoking in this study provide a crucial evidence base in support of the solutions to address spatial disparities in tobacco use and disparate health and economic outcomes.

This study has several limitations.

First, although we incorporated the prevalence of obesity as a proxy for the health behaviour at population level, the smoking status variable might have accounted for any spillover effects of reduced smoking on mortality or morbidity from other risk behaviours associated with smoking (eg, alcohol consumption), or related diseases (eg, diabetes), road traffic accidents, and mental health and substance misuse., Consequently, this study might have overestimated the economic loss attributable to smoking exclusively. Future research should address this bias.

Second, this study estimated the economic burden of cigarette smoking for 2020, which was an atypical year due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidence suggests that smoking might increase the risk of severe COVID-19.

This increased risk could mediate the relationship between smoking and income. However, the year dummies included in the regression model were expected to address this concern by accounting for unusual fluctuations in income seen in 2020. The estimates of annual economic loss for individual years from 2011 to 2019, obtained by the same approach as followed for calculating 2020 estimates, showed no discernible fluctuation in 2020 ( appendix pp 20–21).

Third, smoking imposes some intangible costs on society, including the psychological pain and suffering of individuals and their families caused by smoking-induced diseases, and the anxiety and grief associated with premature deaths from these illnesses. These costs interfere with quality of life and productivity, however, they are not easily quantifiable and might not be fully reflected in the measure of personal income per capita used in this current analysis.

References and additional information:

See the original publication

Originally published at https://www.thelancet.com.