The Lancet Public

Kim R van Daalen, MPhil, Marina Romanello, PhD

Prof Joacim Rocklöv, PhD

Prof Jan C Semenza, PhD

Cathryn Tonne, ScD

Prof Anil Markandya, PhD et all

October 25, 2022

Site Editor:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

health transformation institute (HTI) — center of excellence

October 25, 2022

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In the past few decades, major public health advances have happened in Europe, with drastic decreases in premature mortality and a life expectancy increase of almost 9 years since 1980.

European countries have some of the best health-care systems in the world. However, Europe is challenged with unprecedented and overlapping crises that are detrimental to human health and livelihoods and threaten adaptive capacity, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the fastest-growing migrant crisis since World War 2, population displacement, environmental degradation, and deepening inequalities. Compared with pre-industrial times, the mean average European surface air temperature increase has been almost 1°C higher than the average global temperature increase, and 2022 was the hottest European summer on record. As the world’s third largest economy and a major contributor to global cumulative greenhouse gas emissions, Europe is a key stakeholder in the world’s response to climate change and has a global responsibility and opportunity to lead the transition to becoming a low-carbon economy and a healthier, more resilient society.

The Lancet Countdown in Europe is a collaboration of 44 leading researchers, established to monitor the links between health and climate change in Europe and to support a robust, evidence-informed response to protect human health.

Mirroring the Global Lancet Countdown, this report monitors the health effects of climate change and the health co-benefits of climate action in Europe. Indicators will be updated on an annual basis and new indicators will be incorporated to provide a broad overview to help guide policies to create a more climate-resilient future.

The health costs of delayed decarbonisation

The 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report exposed how dangerously close the world is to reaching climate-driven points of no return.

Alarming increases in health-related hazards, vulnerabilities, exposures, and impacts from climate change across Europe show the urgent need for ambitious mitigation targets that restrict the global temperature rise to less than 1·5°C above pre-industrial levels and effective adaptation strategies to build resilience to the increasing health threats of climate change.

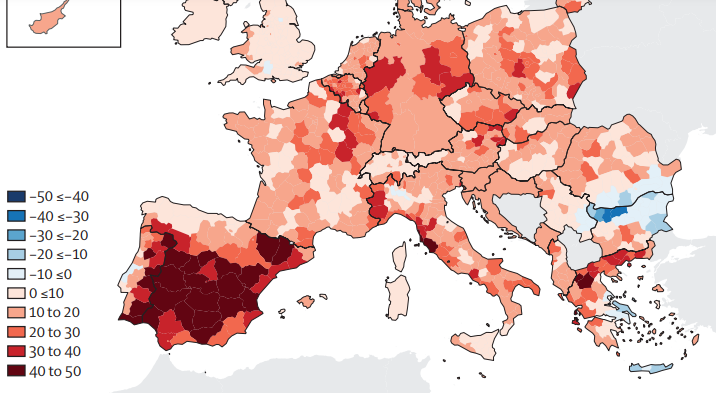

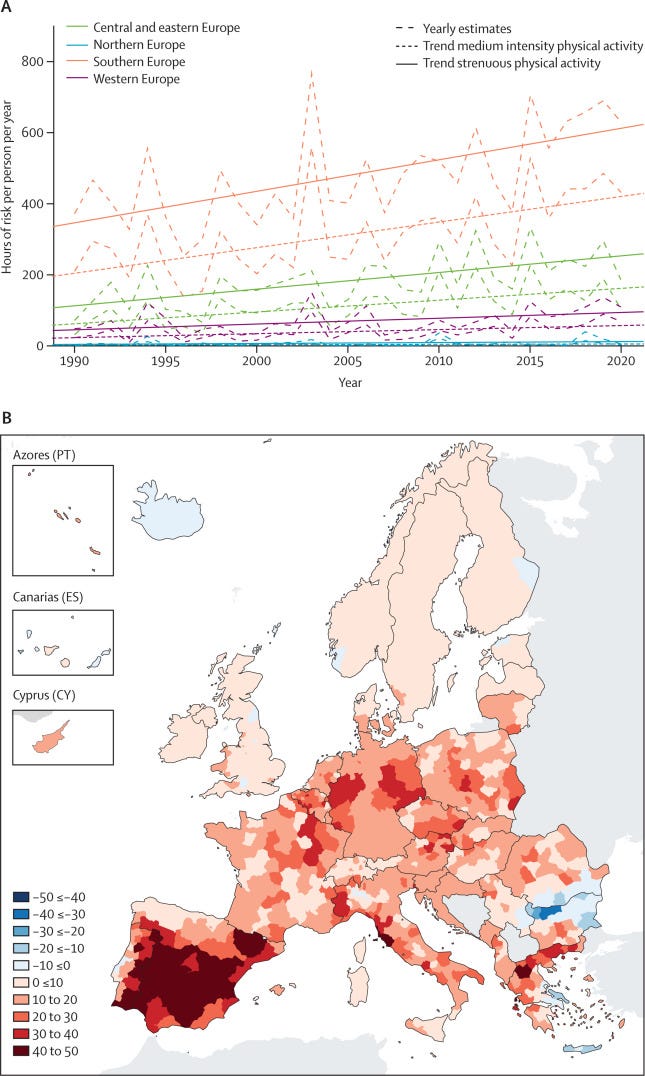

Population exposure to heatwaves increased by 57% on average in 2010–19 compared with 2000–09, and by more than 250% in some regions, …

… putting older people, young children, people with underlying chronic health conditions, and people who do not have adequate access to health care at high risk of heat-related morbidity and mortality (indicator 1.1.2).

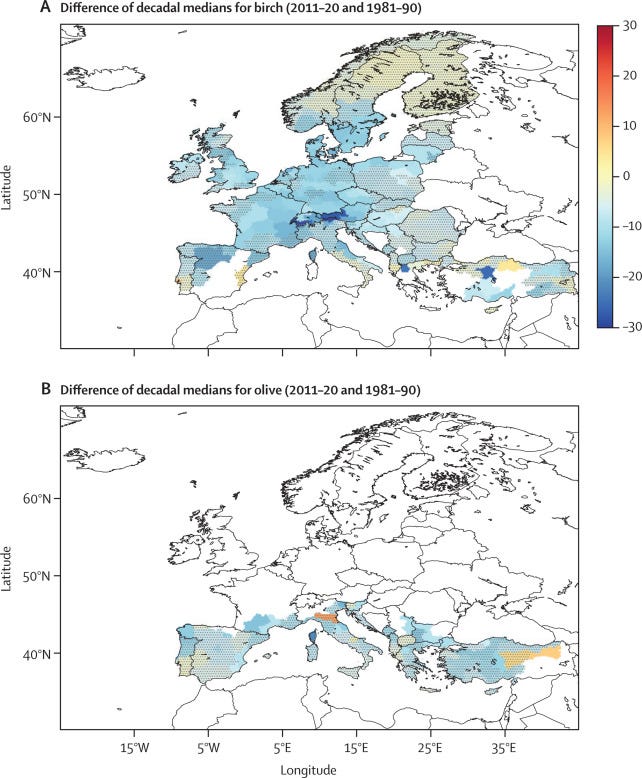

Global warming observed between 2000 and 2020 has been associated with an estimated temperature-related mortality increase in most regions monitored, with an average of 15·1 additional deaths per million inhabitants per decade (95% CI -1·51 to 31·6; indicator 1.1.4). Besides the direct health impacts, heat exposure also undermines people’s livelihoods and the social determinants of health by reducing labour capacity. Labour supply in highly exposed sectors (eg, agriculture) was lower in 2016–19 compared with 1965–94 because of increased heat exposure (indicator 4.1.2). Climate change is also driving increasingly intense and frequent climate-related extreme events in Europe, with both direct and indirect health impacts, loss of infrastructure, and economic costs. Between 2011 and 2020, 55% of the European regions have had extreme-to-exceptional summer drought (indicator 1.2.2), and climate-related extreme events were associated with record economic losses in 2021, totalling almost €48 billion (indicator 4.1.1). The changing environmental conditions are also shifting the environmental suitability for the transmission of various infectious diseases. An increasing percentage of coastal waters in Europe are showing suitable conditions for the transmission of pathogenic non- cholerae Vibrio (indicator 1.3.1), the climatic suitability for the transmission of dengue increased by 30% in the past decade compared with the 1950s (indicator 1.3.3), and the environmental risk of West Nile virus outbreaks increased by 149% in southern Europe and 163% in central and eastern Europe in 1986–2020 compared with 1951–85 (indicator 1.3.2). Warmer temperatures are also shifting flowering seasons of several allergenic tree species, with birch, olive, and alder seasons beginning 10–20 days earlier than 41 years ago, affecting the health of around 40% of the population in Europe who have pollen allergies (indicator 1.4.1).

These overlapping and interconnecting health impacts, which are evolving against a backdrop of a pandemic and a devastating war in Ukraine, reveal the urgent need for interventions that build resilience in the health sector and protect people from increasing health hazards.

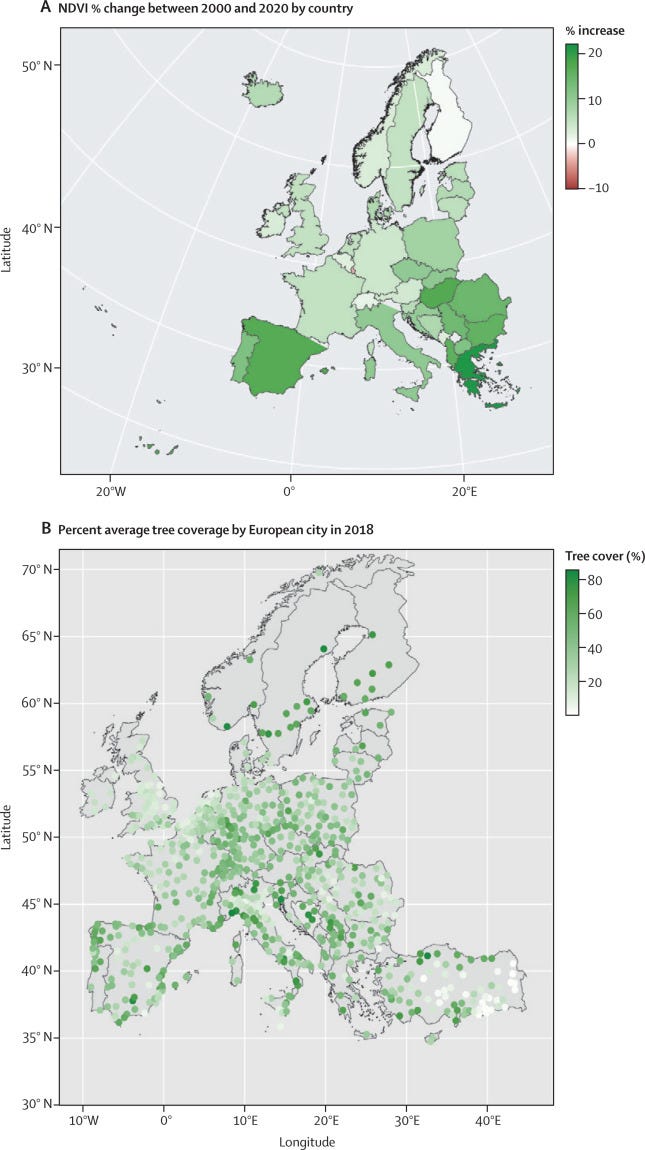

Some progress has been made in Europe’s health adaptation. In 2021, 15 (68%) of 22 European countries reported having national health and climate change strategies or plans (indicator 2.1.2), and 10 (45%) reported conducting a climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment (indicator 2.1.1). 150 European cities (76%) reported performing city-level climate assessments, with 118 (59·9%) reporting that climate change threatens their public health or health services (indicator 2.1.3). Population-weighted greenness increased from 2000 to 2020 in most European countries, with the largest percentage increase in southern Europe and the smallest increase in western Europe (indicator 2.2.2). Climate adaptation often needs to compete for scarce financial resources, and the enactment of adaptation plans alone is not sufficient to advance adaptive capacity. With the impacts of climate change on the rise, adaptation efforts must rapidly accelerate and be carefully implemented alongside mitigation strategies.

In a world 1·2°C warmer than pre-industrial times, the magnitude of the overlapping and interconnected health impacts of climate change is a warning of the consequences of exceeding the 1·5°C target of the Paris Agreement.

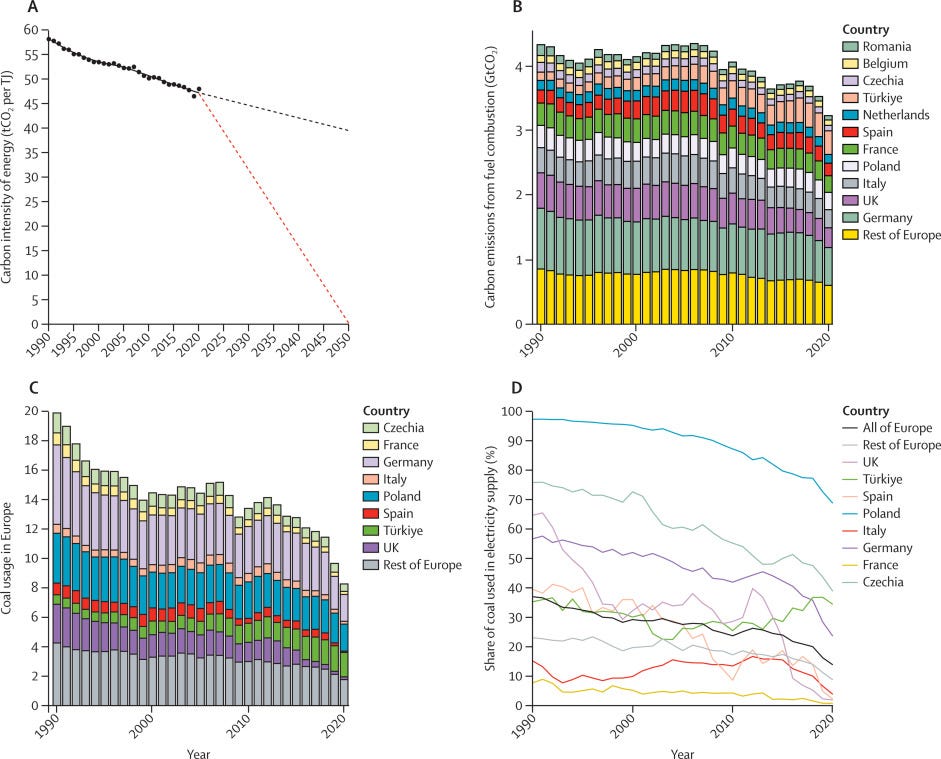

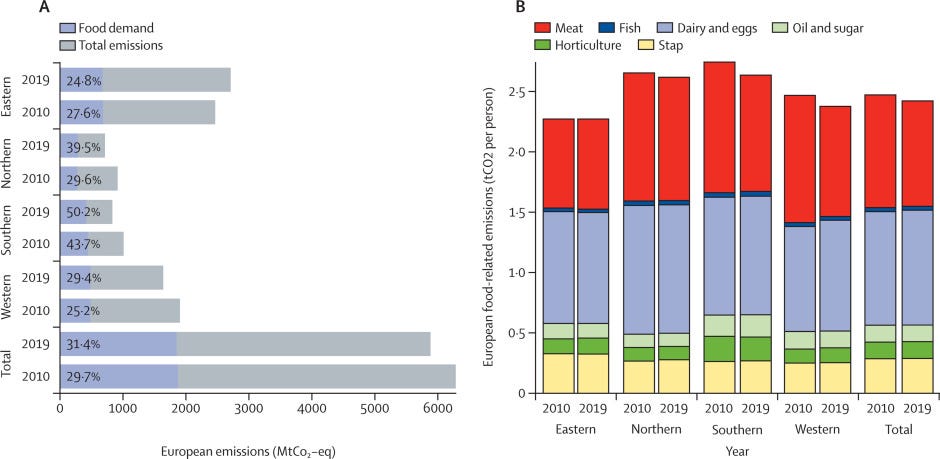

Europe should reach net-zero greenhouse gas emission by 2050 to meet the Paris Agreement commitments. However, Europe’s current emissions are excessively high at 5·6 tonnes (t)CO 2 per person just from the combustion of fossil fuels for energy production (indicator 3.1.1). The region’s delayed response could be costing millions of lives each year, not only by exacerbating the health impacts of climate change, but also given the missed direct and indirect health co-benefits that more ambitious climate action could deliver. The continued burning of fossil fuels led to 117 000 deaths in 2020 from exposure to particulate matter of less than 2·5 μm in diameter (PM 2·5) air pollution, with the transport sector being the main contributor (indicator 3.2). Importantly, coal contributed to 12% of the total energy supply in Europe in 2020, an inefficient fuel source that substantially contributes to air pollution (indicator 3.1.2). The excessive consumption of high-carbon, meat-rich diets contributed to an estimated 2·2 million deaths in 2019 (indicator 3.4.1), and European food demand was estimated to be responsible for 2·5 tCO 2 equivalent (eq) emitted per person, accounting for 37% of the carbon footprint of the average person in EU27 (ie, the 27 countries in the EU after the UK left; indicator 3.4.2). However, despite the clear health impacts of climate change and the substantial health opportunities of climate action, 23 (43%) of 53 European countries analysed are allocating public funds to deliver overall fossil fuel subsidies, financially constraining decarbonisation targets (indicator 4.2.1).

In a world 1·2°C warmer than pre-industrial times, the magnitude of the overlapping and interconnected health impacts of climate change is a warning of the consequences of exceeding the 1·5°C target of the Paris Agreement.

The delayed implementation of locally generated, low-carbon energy sources has made Europe susceptible to volatile energy prices, which reached record high values in 2022.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has shown Europe’s over-reliance on fossil fuels, exacerbating the energy crisis. While the world is trying to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and responding to multiple coinciding disasters, recovery is hindered by the negative climate change impacts on health and its determinants, emphasising the urgent need for action.

A transformational change for health

To avoid a catastrophic increase in global temperatures, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change makes it clear that Europe must fully decarbonise its power sector by 2035, with all coal-fired power plants globally closing by 2040.

Despite the scarce climate action in Europe to date, indicators within this report suggest that change might be underway. Although engagement with the intersection of health and climate change is low compared with overall engagement with climate change more generally, political engagement with health and climate change in the European Parliament has slightly increased since 2014 (indicator 5.3). Engagement of the scientific sector (indicator 5.1) since 2014 and engagement of the corporate sector (indicator 5.4) since 1990 have also increased. These increases have been accompanied by small changes in the energy system; energy generation from renewable sources is increasing at a rate of 16% per year (indicator 3.1.3), and if this rate is maintained, Europe’s energy system could almost fully decarbonise within 10 years.

To avoid a catastrophic increase in global temperatures, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change makes it clear that Europe must fully decarbonise its power sector by 2035, with all coal-fired power plants globally closing by 2040.

Europe’s response to the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis will be important in forming Europe’s new geopolitical situation. The energy crisis and decades of delay in switching to low-carbon energy generation risks a change to greater coal power generation in the short term. Even as a temporary measure, an increase in coal use could add to the approximately 8000 annual deaths associated with coal-fired power plants, in the domestic sector (indicator 3.2), reversing the health gains made in the past decade and undermining efforts to meet Paris Agreement commitments. Increasing Europe’s reliance on fossil fuels would further accelerate global warming, increase air pollution, and be detrimental to health and wellbeing.

The REPowerEU plan published in March, 2022, aiming to accelerate the transition to clean energy sources, provides hope, …

… reaffirming Europe’s leadership in low-carbon systems by providing direct economic benefits, energy sovereignty, and security, the net creation of more equitable jobs, and added health benefits with the reduced burning of fossil fuels.

The indicators in this report show that an accelerated transition to clean energy could save lives each year.

The biggest public health opportunity of the century

With a world dangerously close to reaching climate-driven points of no return and an increasing energy crisis, and with the health of populations increasingly undermined by global warming, Europe is at a crucial point for change.

If climate mitigation and adaptation plans are designed and implemented with health, wellbeing, and equity as the main focus, this could represent the biggest public health policy opportunity of the century. Ambitious European adaptation and mitigation strategies will not only protect lives and wellbeing in Europe, but also in countries that have contributed least to anthropogenic climate change. The danger of reaching a point of no return means that Europe cannot afford to miss such opportunity.

INTRODUCTION

Introduction

Major public health gains have been made in Europe, with life expectancy increases of almost 9 years since 1980.

However, Europe is challenged with unprecedented and overlapping crises that are detrimental to health and threaten resilience to climate change; these include the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, population displacement, environmental degradation, and deepening socioeconomic inequalities.

In Europe, average surface air temperatures have increased by 2·2°C since pre-industrial times (1850–1900), about 1°C higher compared with the corresponding global temperature increase of 1·2°C. The hottest summer on record was in 2022.

Without accelerated mitigation and adaptation, ongoing climate change will have irreversible, multidimensional impacts on human health resulting from exposure to extreme climatic events, heat-related morbidity and mortality, altered environmental suitability, and exposure to infectious diseases.

As the world’s third largest economy, the EU has contributed 17% of global cumulative greenhouse gas emissions (1950–2012).

Europe is a key stakeholder in the world’s response to climate change, and has the opportunity to lead the way in the transition to low carbon, healthier economies, and increased climate resilience.

In 2021, the EU’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions was accepted into law, with the aim to reduce greenhouse gases by at least 55% from emission levels in 1990 by 2030 and reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in Feb, 2022, has brought a new context of political instability and human crisis and highlighted Europe’s dependency on fossil fuel imports. This dependency highlights the urgent need to transition to clean energy sources to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while ensuring energy security and affordability.

This is the first report of the Lancet Countdown Europe.

The report draws on broad expertise, including that of epidemiologists and public health experts, climate scientists, economists, social scientists, and political scientists from 29 leading European academic and UN institutions. Together, 44 contributors report on 33 indicators, monitoring and quantifying the health impacts of climate change and the health co-benefits of accelerated action since the 1950s. The report mirrors that of the global Lancet Countdown report, tracking progress on health and climate change in five areas: climate change impacts, exposures, and vulnerabilities; adaptation, planning, and resilience for health; mitigation actions and health co-benefits; economics and finance; and politics and governance. The geographical coverage of each indicator is reported (appendix pp 4–5), with most indicators covering all 38 European Environment Agency (EEA) member and cooperating countries, plus the UK. Methods and underlying data are presented in the appendix (pp 12–193).

CONCLUSION

Conclusion of the 2022 European report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change

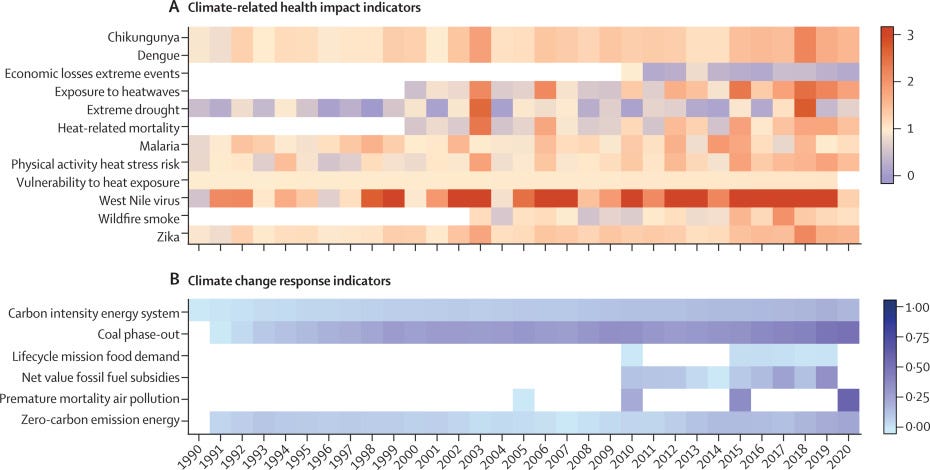

This report provides the first comprehensive assessment of progress on health and climate change in Europe by tracking 33 indicators in the domains of impact, exposure, and vulnerability (section 1); adaptation, planning, and resilience (section 2); mitigation actions and health co-benefits (section 3); economics and finance (section 4); and politics and governance (section 5). Europe is facing many catastrophic events that threaten the security and livelihoods of populations across Europe and globally. The Lancet Countdown in Europe highlights the accelerating trends in health-related hazards, exposures, vulnerabilities, and risks from climate change, and insufficiently ambitious adaptation and mitigation strategies (figure 10).

Figure 10 — Overview of standardised impacts and responses tracked in the 2022 European report of the Lancet Countdown

The health risks for almost all indicators tracked here are increasing in Europe. Clinically relevant pollen seasons are starting earlier each year (indicator 1.4) and climate suitability for water-borne and vector-borne diseases is rapidly increasing (indicators 1.3.1 to 1.3.4). Assuming no adaptation, heat exposure has increased by 57% between the first and second decade of the 21st century; exercising under extreme heat is posing acute health risks; and heat-related deaths are increasing (indicators 1.1.1 to 1.1.4). The frequency of extreme drought in affected areas has increased in the past decade (indicator 1.2.2). By contrast, wildfire smoke exposure did not increase during the period 2003–20, despite an increase in meteorological fire risk, likely resulting from effective fire prevention and suppression measures (indicator 1.2.1).

Heterogeneous geographical patterns of these impacts are observed across Europe, with many indicators reflecting highest absolute risk and increasing climate suitability for infectious diseases in central and southern Europe. Health risks paired with substantial economic losses related to climate, such as climate-related extreme events, reduced labour supply, and reduced GDP per capita growth (section 4). Without intervention, these impacts are likely to worsen in the coming years.

There are some encouraging trends in adaptation in parts of Europe, with select countries and cities adopting adaptation plans for health, doing health risks assessments, implementing early warning systems, and increasing green space exposure (section 2). Although there has been some progress in reducing the carbon intensity of the energy system and phasing out coal for electricity generation, mitigation efforts have been inadequate to meet 2030 and 2050 reduction targets (indicator 3.1.1 to 3.1.3). The pace of decarbonisation for electricity generation, residential heating, and transport in Europe does not support efforts to meet WHO guidelines for safe ambient PM2·5 concentrations and would need to accelerate five-fold (indicator 3.1.1) to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 (indicators 3.1 to 3.3). Little progress has been made in the adoption of more sustainable, healthy diets, resulting in greenhouse gas emissions and thousands of deaths from high-carbon, animal-based diets (indicator 3.4). European countries provide overall subsidies for fossil fuels, providing financial constraints to meeting decarbonisation targets (indicator 4.2.1). Strengthening the response to the health impacts of climate change requires key actors and institutions to engage with the health dimensions of climate change to create a supportive political context. However, when comparing political engagement and individual online engagement of climate change and health with climate change engagement more broadly, engagement is still relatively low (indicators 5.2 and 5.3).

Without urgent acceleration in mitigation and adaptation efforts, the health impacts of climate change are likely to worsen in the coming years, affecting the wellbeing and lives of millions of people.

The implementation of ambitious mitigation and adaptation strategies will not only protect lives and human wellbeing in Europe, but also in countries that have historically contributed least to anthropogenic climate change.

The current energy security threats and volatile energy prices further highlight the co-benefits of the transition to renewable energy, increasing energy independence and resilience.

This report highlights the urgent need and opportunities for accelerated action in line with climate targets; to support a healthy, climate-resilient future for all people.

Without urgent acceleration in mitigation and adaptation efforts, the health impacts of climate change are likely to worsen in the coming years, affecting the wellbeing and lives of millions of people.

This report highlights the urgent need and opportunities for accelerated action in line with climate targets; to support a healthy, climate-resilient future for all people.

Infographic

Originally published at https://www.thelancet.com.

About the authors & affiliations

Kim R van Daalen, MPhil,

Marina Romanello, PhD

Prof Joacim Rocklöv, PhD

Prof Jan C Semenza, PhD

Cathryn Tonne, ScD

Prof Anil Markandya, PhD et all