This is a republication of the article “Loneliness is a serious public-health problem”, published in 2018 by “The Economist”, but that remains actual, even more with the experiences of the Covid-19 Pandemic.

mental health institute

@ health transformation institutes

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Chief Researcher, Editor and

Senior Advisor

January 14, 2023

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Loneliness is a growing public-health concern in the rich world, with campaigns being launched in several countries to reduce it.

- In Japan, the government has surveyed hikikomori, or “people who shut themselves in their homes”.

- Last year Vivek Murthy (2017), a former Surgeon General of the United States, called loneliness an epidemic, likening its impact on health to obesity or smoking 15 cigarettes per day.

The Economist and the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), an American non-profit group focused on health, surveyed nationally representative samples of people in three rich countries and found that

- 9% of adults in Japan, 22% in America and 23% in Britain always or often feel lonely, or lack companionship, or else feel left out or isolated.

Loneliness is defined as perceived social isolation, a feeling of not having the social contacts one would like.

Loneliness has been described as a serious public-health problem, with campaigns being launched in several countries to reduce it.

- But research on rates of reported loneliness does not support the view that rich, individualistic societies are lonelier than others.

- A study published in 2015 by Thomas Hansen and Britt Slagvold of Oslo Metropolitan University found that “quite severe” loneliness ranged from 30–55% in southern and eastern Europe, versus 10–20% in western and northern Europe.

- The study pointed to two explanations, the most important is that southern and eastern European countries are generally poorer, with patchier welfare states.

- The second reason concerns culture.

- The authors argued that in countries where older people expect to live near and be cared for by younger relatives, the shock when that does not happen is greater.

Technology is also being blamed for a rise in loneliness in young people.

- While it is plausible, it is not clear whether it is heavy social-media use leading to loneliness, or vice versa.

- Others are sure that technology can reduce loneliness, social robots and devices such as Komp and AV1 are being developed to keep people connected and reduce feelings of isolation.

INFOGRAPHIC

DEEP DIVE

Loneliness is a serious public-health problem

The Economist

1 de set. de 2018

LONDON, says Tony Dennis, a 62-year-old security guard, is a city of “sociable loners”. Residents want to get to know each other but have few ways to do so. Tonight, however, is different. Mr Dennis and a few dozen other locals are jousting at a monthly quiz put on by the Cares Family, a charity dedicated to curbing loneliness.

The competitors are a deliberate mix of older residents and young professionals new to the area. “Young people are increasingly feeling disconnected too,” argues Alex Smith, the charity’s 35-year-old founder. He hopes that nights like this will foster a sense of belonging.

Doctors and policymakers in the rich world are increasingly worried about loneliness.

Campaigns to reduce it have been launched in Britain, Denmark and Australia.

In Japan the government has surveyed hikikomori, or “people who shut themselves in their homes”.

Last year Vivek Murthy, a former surgeon-general of the United States, called loneliness an epidemic, likening its impact on health to obesity or smoking 15 cigarettes per day.

In January Theresa May, the British prime minister, appointed a minister for loneliness.

That the problem exists is obvious; its nature and extent are not. Obesity can be measured on scales. But how to weigh an emotion?

Researchers start by distinguishing several related conditions.

Loneliness is not synonymous with social isolation (how often a person meets or speaks to friends and family) or with solitude (which implies a choice to be alone).

Instead researchers define loneliness as perceived social isolation, a feeling of not having the social contacts one would like.

Loneliness is not synonymous with social isolation (how often a person meets or speaks to friends and family) or with solitude (which implies a choice to be alone).

Instead researchers define loneliness as perceived social isolation, a feeling of not having the social contacts one would like.

Of course, the objectively isolated are much more likely than the average person to feel lonely.

But loneliness can also strike those with seemingly ample friends and family.

Nor is loneliness always a bad thing.

John Cacioppo, an American psychologist who died in March, called it a reflex honed by natural selection.

Early humans would have been at a disadvantage if isolated from a group, he noted, so it makes sense for loneliness to stir a desire for company.

Transient loneliness still serves that purpose today. The problem comes when it is prolonged.

To find out how many people feel this way, The Economist and the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), an American non-profit group focused on health, surveyed nationally representative samples of people in three rich countries.*

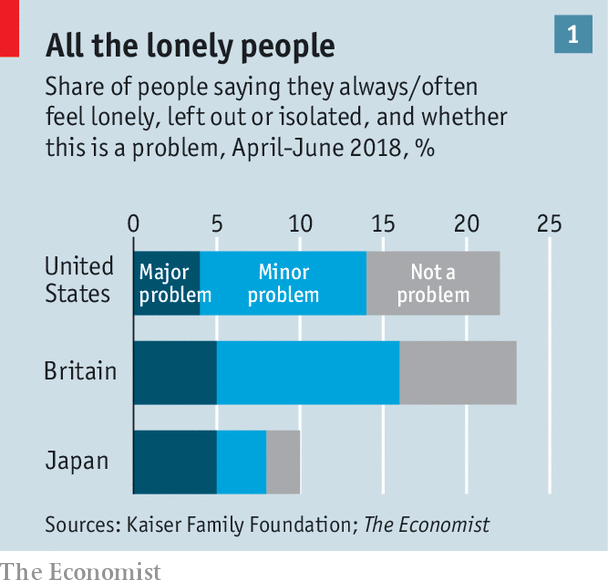

The study found that 9% of adults in Japan, 22% in America and 23% in Britain always or often feel lonely, or lack companionship, or else feel left out or isolated (see chart 1).

The study found that 9% of adults in Japan, 22% in America and 23% in Britain always or often feel lonely, or lack companionship, or else feel left out or isolated

The findings complement academic research which uses standardised questionnaires to measure loneliness.

One drawn up at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), has 20 statements, such as “I have nobody to talk to”, and “I find myself waiting for people to call or write”.

Responses are marked based on the extent to which people agree. Respondents with tallies above a threshold are classed as lonely.

A study published in 2010 using this scale estimated that 35% of Americans over 45 were lonely.

Of these 45% had felt this way for at least six years; a further 32% for one to five years.

In 2013 Britain’s Office for National Statistics (ONS), by dint of asking a simple question, classed 25% of people aged 52 or over as “sometimes lonely” with an extra 9% “often lonely”.

Other evidence points to the extent of isolation.

For 41% of Britons over 65, TV or a pet is their main source of company, according to Age UK, a charity.

In Japan more than half a million people stay at home for at least six months at a time, making no contact with the outside world, according to a report by the government in 2016.

Another government study reckons that 15% of Japanese regularly eat alone. A popular TV show is called “The Solitary Gourmet”.

For 41% of Britons over 65, TV or a pet is their main source of company, according to Age UK, a charity.

Is your heart filled with pain?

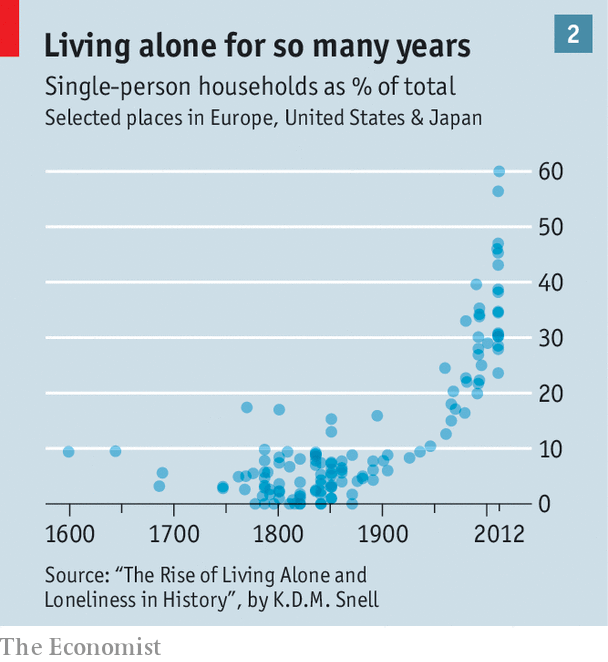

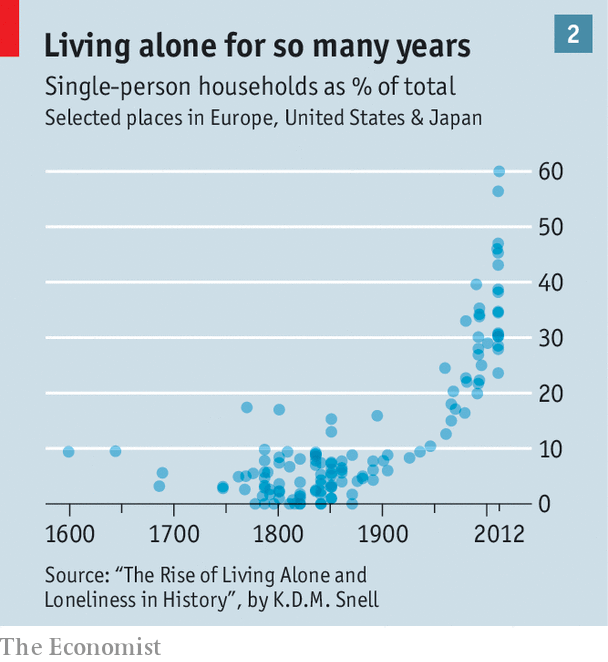

Historical data about loneliness are scant. But isolation does seem to be increasing, so loneliness may be too. Consider the rise in solitary living (see chart 2).

Before 1960 the share of solo households in America, Europe or Japan rarely rose above 10%.

Today in cities such as Stockholm most households have just one member.

Many people opt to live alone, as a mark of independence.

But there are also many in rich countries who live solo because of, say, divorce or a spouse’s death.

Isolation is increasing in other ways, too.

From 1985 to 2009 the average size of an American’s social network-defined by number of confidants-declined by more than one-third.

Other studies suggest that fewer Americans join in social communities like church groups or sports teams.

The idea that loneliness is bad for your health is not new.

One early job of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in the Yukon region was to keep tabs on the well-being of gold prospectors who might go months without human contact.

Evidence points to the benign power of a social life.

Suicides fall during football World Cups, for example, maybe because of the transient feeling of community.

But only recently has medicine studied the links between relationships and health.

In 2015 a meta-analysis led by Julianne Holt-Lunstad of Brigham Young University, in Utah, synthesised 70 papers, through which 3.4m participants were followed over an average of seven years.

She found that those classed as lonely had a 26% higher risk of dying, and those living alone a 32% higher chance, after accounting for differences in age and health status.

Smaller-scale studies have found correlations between loneliness and isolation, and a range of health problems, including heart attacks, strokes, cancers, eating disorders, drug abuse, sleep deprivation, depression, alcoholism and anxiety.

Some research suggests that the lonely are more likely to suffer from cognitive decline and a quicker progress of Alzheimer’s disease.

Smaller-scale studies have found correlations between loneliness and isolation, and a range of health problems, including heart attacks, strokes, cancers, eating disorders, drug abuse, sleep deprivation, depression, alcoholism and anxiety.

Researchers have three theories as to how loneliness may lead to ill health, says Nicole Valtorta of Newcastle University.

The first covers behaviour. Lacking encouragement from family or friends, the lonely may slide into unhealthy habits.

The second is biological. Loneliness may raise levels of stress, say, or impede sleep, and in turn harm the body.

The third is psychological, since loneliness can augment depression or anxiety.

Or is it the other way round? Maybe sick people are more likely to be lonely.

In the KFF/ Economist survey six out of ten people who said they were lonely or socially isolated blamed specific causes such as poor mental or physical health.

Three out of ten said their loneliness had made them think about harming themselves.

Research led by Marko Elovainio of the University of Helsinki and colleagues, using the UK Biobank, a voluntary database of hundreds of thousands of people, suggests that the relationship runs both ways: loneliness leads to ill health, and vice versa.

Research … suggests that the relationship runs both ways: loneliness leads to ill health, and vice versa.

Other studies show more about the causes of loneliness.

A common theme is the lack of a partner.

Analysis of the survey data found that married or cohabiting people were far less lonely.

Having a partner seems especially important for older people, as generally they have fewer (but often closer) relationships than the young do.

Other studies show more about the causes of loneliness. A common theme is the lack of a partner.

Having a partner seems especially important for older people, as generally they have fewer (but often closer) relationships than the young do.

Yet loneliness is not especially a phenomenon of the elderly.

The polling found no clear link between age and loneliness in America or Britain-and in Japan younger people were in fact lonelier.

Young adults, and the very old (over-85s, say) tend to have the highest shares of lonely people of any adult age-group.

Other research suggests that, among the elderly, loneliness tends to have a specific cause, such as widowhood.

In the young it is generally down to a gap in expectations between relationships they have and those they want.

Whatever their age, some groups are much more likely to be lonely.

One is people with disabilities. Migrants are another. A study of Polish immigrants in the Netherlands published in 2017 found that they reported much higher rates of loneliness than Dutch-born people aged between 60 and 79 (though female migrants tended to cope better than their male peers).

A survey by a Chinese trade union in 2010 concluded that “the defining aspect of the migrant experience” is loneliness.

Regions left behind by migrants, such as rural China, often have higher rates of loneliness, too. A study of older people in Anhui province in eastern China published in 2011 found that 78% reported “moderate to severe levels of loneliness”, often as a result of younger relatives having moved.

Similar trends are found in eastern Europe where younger people have left to find work elsewhere.

Loneliness is usually best explained as the result of individual factors such as disability, depression, widowhood or leaving home without your partner.

Yet some commentators say larger forces, such as “neoliberalism”, are at work.

Where do they all come from?

In fact, it is hard to prove that an abstract noun is creating a feeling.

And research on rates of reported loneliness does not support the view that rich, individualistic societies are lonelier than others.

A study published in 2015 by Thomas Hansen and Britt Slagvold of Oslo Metropolitan University, for example, found that “quite severe” loneliness ranged from 30–55% in southern and eastern Europe, versus 10–20% in western and northern Europe.

“It is thus a paradox that older people are less lonely in more individualistic and less familistic cultures,” concluded the authors.

Their research pointed to two explanations.

The most important is that southern and eastern European countries are generally poorer, with patchier welfare states.

The second reason concerns culture. The authors argued that in countries where older people expect to live near and be cared for by younger relatives, the shock when that does not happen is greater.

Another villain in the contemporary debate is technology.

Smartphones and social media are blamed for a rise in loneliness in young people. This is plausible. Data from the OECD club of mostly rich countries suggest that in nearly every member country the share of 15-year-olds saying that they feel lonely at school rose between 2003 and 2015.

The smartphone makes an easy scapegoat. A sharp drop in how often American teenagers go out without their parents began in 2009, around when mobile phones became ubiquitous.

Rather than meet up as often in person, so the story goes, young people are connecting online.

But this need not make them lonelier.

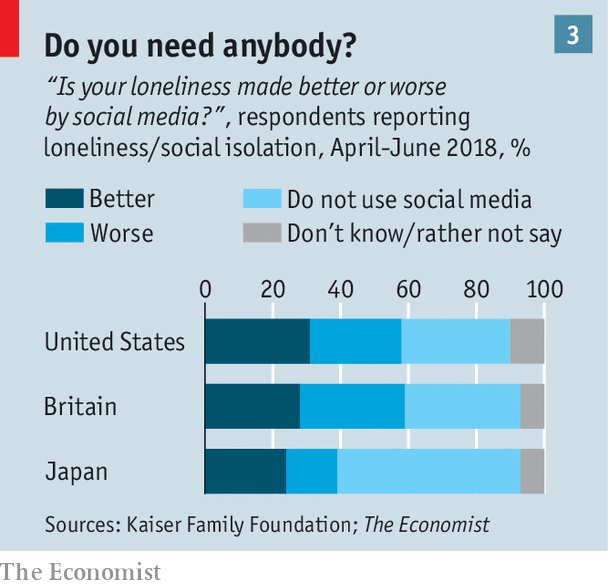

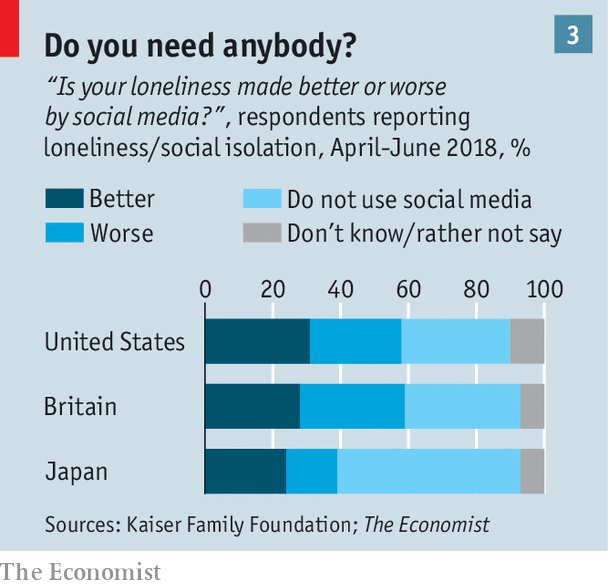

Snapchat and Instagram may help them feel more connected with friends. Of those who said they felt lonely in the KFF/ Economist survey, roughly as many found social media helpful as thought it made them feel worse (see chart 3).

Yet some psychologists say that scrolling through others’ carefully curated photos can make people feel they are missing out, and lonely.

In a study of Americans aged 19 to 32, published in 2017, Brian Primack of the University of Pittsburgh, and colleagues, found that the quartile that used social media most often was more than twice as likely to report loneliness as the one using it least.

It is not clear whether it is heavy social-media use leading to loneliness, or vice versa.

Other research shows that the correlation between social-media use and, say, depression is weak.

The most rigorous recent study of British adolescents’ social-media use, published by Andrew Przybylski and Netta Weinstein in 2017, found no link between “moderate” use and measures of well-being.

They found evidence to support their “digital Goldilocks hypothesis”: neither too little nor too much screen time is probably best.

Know the way I feel tonight

Others are sure that technology can reduce loneliness.

On the top of a hill in Gjøvik, a two-hour train-ride from Oslo, lives Per Rolid, an 85-year-old widowed farmer.

One daughter lives nearby, but he admits feeling lonely. So he has agreed to take part in a trial of Komp, a device made by No Isolation, a startup founded in 2015.

It consists of a basic computer screen, a bit like an etch-a-sketch. The screen rotates pictures sent by his grandchildren, and messages in large print from them and other kin.

No Isolation also makes AV1, a fetching robot in the form of a disembodied white head with cameras in its eye-sockets. It allows users, often out-of-school children with chronic diseases, to feel as if they are present in class. AV1 can be put on a desk so absent children can follow goings-on. If they want to ask a question, they can press a button on the AV1 app and the top of the robot’s head lights up.

So-called “social robots”, such as Paro, a cuddly robotic seal, have been used in Japan for some time. But they are becoming more sophisticated. Pepper, a human-ish robot made by a subsidiary of SoftBank, a Japanese conglomerate, can follow a person’s gaze and adapt its behaviour in response to humans. Last year the council in Southend, an English seaside town, began deploying Pepper in care homes.

Other health-care providers are experimenting with virtual reality (VR). In America UCHealth is conducting trials of VR therapy that allow some cancer patients to have “bucket list” experiences, such as skiing in Colorado.

In 2016, Liminal, an Australian VR firm, teamed up with Medibank, an insurance company, to build a virtual experience for lonely people who could not leave their hospital beds.

As technology becomes more human it may be able to do more and more to substitute for human relationships.

In the meantime, services that offer human contact to the lonely will thrive. In Japan this manifests itself in agencies and apps that allow you to rent a family or a friend-a girlfriend for a singleton, a funeral mourner, or simply a companion to watch TV with.

Such products are not just Japanese quirks.

One Caring Team, an American company, calls and checks in on lonely elderly relatives for a monthly fee.

The Silver Line, a similar (but free) helpline, is run by a British charity. Launched in 2013 it takes nearly 500,000 calls a year.

Its staff in their Blackpool headquarters are supported by volunteers across the country in the Silver Friend service, a regular, pre-arranged call between a volunteer and an old person.

Most conversations last about 15 minutes. Those contacting the helpline during your correspondent’s visit started on a general topic-the weather, pets, what they did that morning.

Their real reason for calling only emerged later, through an offhand comment. Often that referred to the need for a partner and the companionship that would bring. Others call in but barely talk, noted one Silver Line staff member.

For many, phone calls are no substitute for company.

Nesterly, founded in 2016, is designed to make it easier for older singletons with spare rooms to rent them to young people who help in the house for a discount on rent.

The platform has “stumbled into loneliness”, notes Noelle Marcus, its co-founder. Users sign up to the platform and create a profile, then make a listing for their room. Last year the startup teamed up with the city of Boston, Massachusetts, to test the initiative across the city.

Similar schemes are run by Homeshare, a network of charities, operating in 16 countries, including Britain.

Elsewhere policymakers are experimenting with incentives to encourage old and young to mix.

In cities such as Lyon in France, Deventer in the Netherlands and Cleveland in Ohio, nursing homes or local authorities are offering students free or cheap rent in exchange for helping out with housework.

That so many startups want to “disrupt” loneliness helps. But most of the burden will be shouldered by health systems.

Some firms are trying to tackle the problem at root.

Last year CareMore, an American health-care provider owned by Anthem, an insurer, launched a dedicated scheme. “We’re trying to reframe loneliness as a treatable medical condition,” explains Sachin Jain, its president.

Last year CareMore, an American health-care provider owned by Anthem, an insurer, launched a dedicated scheme. “We’re trying to reframe loneliness as a treatable medical condition,” explains Sachin Jain, its president.

All by myself

This means, first, screening its 150,000 patients for loneliness. Those at risk are asked if they want to enroll in a “Togetherness Programme”. This involves phone calls from staff called “connectors” who help with transport to events and ideas for socialising.

Patients are coaxed to visit clinics, even when not urgently ill, to play games, attend a “seniors’ gym” and just chat.

For its part, England’s National Health Service is increasingly using “social prescribing”, sending patients to social activities rather than giving them drugs.

More than 100 such programmes are running in Britain. Yet last year a review of 15 papers concluded that evidence to date was too weak to support any conclusions about the programmes’ effectiveness.

This reflects poorly on the state of thinking about loneliness.

There are plenty of reasons to take its effects on health seriously. But the quality of evidence about which remedies work is woeful.

Sadly, therefore, loneliness is set to remain a subject that causes a huge amount of angst without much relief.

For its part, England’s National Health Service is increasingly using “social prescribing”, sending patients to social activities rather than giving them drugs.

Originally published at https://www.economist.com on September 1, 2018.

RELATED PUBLICATION

A detailed report on the survey’s results can be found at https://www.kff.org/other/report/loneliness-and-social-isolation-in-the-united-states-the-united-kingdom-and-japan-an-international-surveyCorrection (August 31st, 2018): A previous version of this piece said that UCHealth was conducting trials in care homes. It is not. This has been changed.

KEY FINDINGS

Some of the key findings from the survey across all three countries are as follows.

- 1.More than two in ten report loneliness or social isolation in the U.K. and the U.S., double the share in Japan.

- 2.Loneliness appears to occur in parallel with reports of real life problems and circumstances.

Across the three countries, people reporting loneliness are more likely to report being down and out physically, mentally, and financially.

- 3.Those reporting loneliness appear to lack meaningful connections with others.

- 4.Among the public at large, across countries, many have heard of the issue but views vary on the reasons for loneliness and who is responsible for helping to reduce it.

- 5.Some are critical of the role technology plays in loneliness and isolation, but some see social media as an opportunity for connection.

- 6.Despite fewer people in Japan reporting loneliness, reports of the severity of the experience are worse.

1.More than two in ten report loneliness or social isolation in the U.K. and the U.S., double the share in Japan.

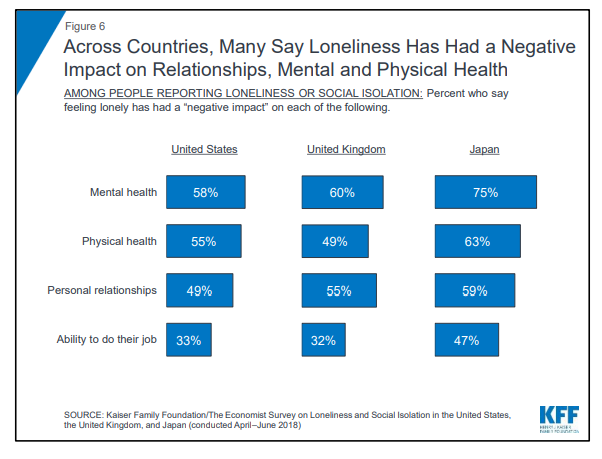

More than a fifth of adults in the United States (22 percent) and the United Kingdom (23 percent) as well as one in ten adults (nine percent) in Japan say they often or always feel lonely, feel that they lack companionship, feel left out, or feel isolated from others, and many of them say their loneliness has had a negative impact on various aspects of their life. For example, across countries, about half or more reporting loneliness say it has had a negative impact on their personal relationships or their physical health. While loneliness is often thought of as a problem mainly affecting the elderly, the majority of people reporting loneliness in each country are under age 50. They’re also much more likely to be single or divorced than others.

2.Loneliness appears to occur in parallel with reports of real life problems and circumstances. Across the three countries, people reporting loneliness are more likely to report being down and out physically, mentally, and financially.

People experiencing loneliness disproportionately report lower incomes and having a debilitating health condition or mental health conditions. About six in ten say there is a specific cause of their loneliness, and, compared to those who are not lonely, they more often report being dissatisfied with their personal financial situation. They are also more likely to report experiencing negative life events in the past two years, such as a negative change in financial status or a serious illness or injury. Three in ten say their loneliness has led them to think about harming themselves.

3.Those reporting loneliness appear to lack meaningful connections with others.

Those reporting loneliness in each country report having fewer confidants than others and two-thirds or more say they have just a few or no relatives or friends living nearby who they can rely on for support. While individuals who report loneliness are more likely to express dissatisfaction with the number of meaningful connections they have with family, friends and neighbors, in the U.K. and the U.S., many still report talking to family and friends frequently by phone or in person. In Japan, reports of communication with family and friends are much less frequent, regardless of whether someone reports loneliness.

4.Among the public at large, across countries, many have heard of the issue but views vary on the reasons for loneliness and who is responsible for helping to reduce it.

Across the U.S., the U.K. and Japan, majorities say they have heard at least something about the issues of loneliness and social isolation in their country. In the U.S., the public is divided as to whether loneliness and social isolation are more of a public health problem or more of an individual problem (47 percent vs. 45 percent), and a large majority (83 percent) see individuals and families themselves playing a major role in helping to reduce loneliness and social isolation in society today and fewer see a major role for government (27 percent). In contrast, residents of the U.K. and Japan are more likely to see the issue as a public health problem than an individual issue (66 percent vs. 27 percent in the U.K. and 52 percent vs. 41 percent in Japan). And, while large majorities in the U.K. and Japan also think individuals and families should play a major role in stemming the problem, six in ten also see a major role for government, unlike in the U.S. A majority of people in the U.K. say “cuts in government social programs” is a major reason why people there are lonely or socially isolated, compared to minorities in the U.S. and Japan.

5.Some are critical of the role technology plays in loneliness and isolation, but some see social media as an opportunity for connection.

Many in the U.S. (58 percent) and U.K. (50 percent) view the increased use of technology as a major reason why people are lonely or socially isolated, whereas fewer people in Japan say the same (26 percent). Across countries, more say technology in general has made it harder to spend time with friends and family in person than say it has made it easier. However, when it comes to social media specifically, in each country, more say that they think their ability to connect with others in a meaningful way is strengthened by social media rather than weakened. But, for those experiencing loneliness or social isolation personally in the U.K. and the U.S., they are divided as to whether they think social media makes their feelings of loneliness better or worse. In addition, people who report being socially isolated or lonely in each country are not more likely than their peers to report using social media.

6.Despite fewer people in Japan reporting loneliness, reports of the severity of the experience are worse.

Half of those experiencing loneliness in Japan (or 5 percent of residents of Japan overall) say it is a major problem for them, compared to a fifth of those experiencing loneliness in the U.S. and the U.K. In Japan, more than a third (35 percent) of those who selfidentify as lonely say they have felt isolated or lonely for more than 10 years, compared to a fifth of those in the U.S. (22 percent) or the U.K. (20 percent). Half of those reporting loneliness in Japan report dissatisfaction with their family life or employment situation and two thirds say the same about their financial situation. Higher shares in Japan than in the U.S. or U.K. say their loneliness has had a negative impact on their job and their mental health. Many people reporting loneliness in Japan are younger — nearly six in ten are less than 50 years old, compared to 42 percent who don’t report loneliness. People in Japan experiencing loneliness are also much more likely to be dissatisfied with the number of meaningful connections they have with friends. More generally, large majorities in Japan think the Japanese concepts of Hikikomori and Kodokishi are serious problems.

Coping with Loneliness

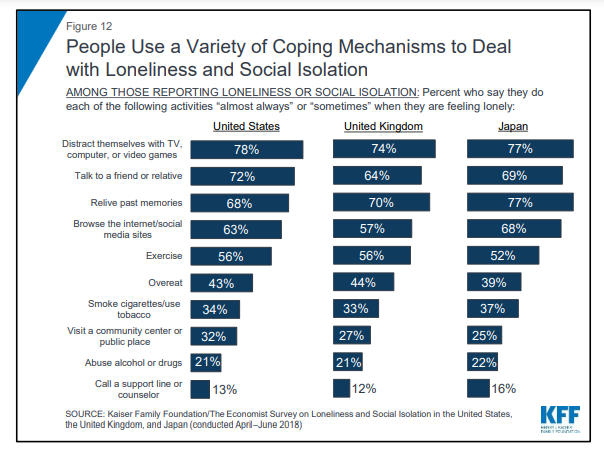

There are a number of different ways people may cope with loneliness, some more positive than others.

- Across countries, the most commonly reported coping mechanisms were distracting oneself with television, or computer or video games and reliving memories from the past, with about seven in ten or more saying they almost always or sometimes do these things when they feel lonely.

- Majorities report talking to a friend or relative, browsing the internet or social media sites or exercising.

- On the more negative side, across countries, four in ten say they overeat at least sometimes when feeling lonely, a third or more say they at least sometimes smoke cigarettes or use other tobacco products when feeling lonely, and two in ten say they at least sometimes abuse alcohol or drugs.