Advisory Board

August 29, 2022

Key messages by:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Health Transformation Journal

Mental Health Institute

September 4, 2022 cnet

- A longer duration of loneliness was associated with accelerated memory aging.

- The association was stronger among women than men and among older adults than the younger.

- Reducing loneliness in mid- to late life may help maintain memory function.

… cumulative duration of loneliness in mid- to late life may be a salient risk factor for accelerated memory aging, especially among women aged 65 and over.

Long-term feelings of loneliness may worsen memory function and speed up cognitive decline, particularly among women and older adults, according to a new study published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Study details and key findings

For the study, researchers from the University of Michigan School of Public Health used data from the National Institute of Aging’s Health and Retirement study to create a longitudinal model that measured the association between loneliness and memory function in participants.

The study included 9,032 adults ages 50 and older. Researchers assessed participants’ loneliness status biennially between 1996 and 2004. The duration of loneliness was classified by the number of time points participants answered they were lonely (0, 1, 2, 3+ time points).

Of the participants, 61.04% did not report being lonely at any time, 17.99% reported being lonely at one point in time, 9.13% reported being lonely at two points in time, and 11.84% reported being lonely at three or more points in time.

Next, researchers assessed episodic memory between 2004 and 2016 using immediate and delayed recall of a 10-word list read aloud by an interviewer.

For participants who were too impaired to participate in interviews, a proxy interview was conducted with a family member or friend to assess the participants’ overall memory.

Researchers found that a longer duration of loneliness was associated with both lower memory scores and faster cognitive decline. This association was strongest among women, as well as participants ages 65 and older.

Researchers found that a longer duration of loneliness was associated with both lower memory scores and faster cognitive decline. This association was strongest among women, as well as participants ages 65 and older.

“Our study finds that there is an association between loneliness and memory aging, suggesting that society, family members, or friends and neighbors should pay attention to older adults’ emotional support or social support as we find that loneliness has a tremendous effect on the individual’s memory aging,” said Xuexin Yu, one of the study’s authors.

“And, given the increasing prevalence of loneliness, particularly during the COVID pandemic, it’s very important to take care of older adults’ loneliness status.”

“Our study finds that there is an association between loneliness and memory aging, …

… suggesting that society, family members, or friends and neighbors should pay attention to older adults’ emotional support or social support as we find that loneliness has a tremendous effect on the individual’s memory aging

“And, given the increasing prevalence of loneliness, particularly during the COVID pandemic, it’s very important to take care of older adults’ loneliness status.”

Commentary

According to Steve Cole, a professor of medicine at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at the University of California, Los Angeles, loneliness can contribute to and exacerbate several other diseases.

“The biology of loneliness can accelerate the buildup of plaque in arteries, help cancer cells grow and spread, and promote inflammation in the brain leading to Alzheimer’s disease,” Cole said.

“Loneliness promotes several types of wear and tear on the body.”

“The biology of loneliness can accelerate the buildup of plaque in arteries, help cancer cells grow and spread, and promote inflammation in the brain leading to Alzheimer’s disease,” …

“Loneliness promotes several types of wear and tear on the body.”

In addition, Elena Portacolone, an associate professor of sociology at the Institute for Health and Aging at the University of California, San Francisco, noted that structural factors, particularly in high-crime neighborhoods, may also impact older adults’ social isolation and subsequently their health.

… structural factors, particularly in high-crime neighborhoods, may also impact older adults’ social isolation and subsequently their health.

“The primary takeaway from this research is that interventions to increase older adults’ social integration should address not only their behaviors, but their overall surroundings,” Portacolone said.

“The primary takeaway from this research is that interventions to increase older adults’ social integration should address not only their behaviors, but their overall surroundings

“We need to concentrate our attention on the influence of social policies, institutions, and ideologies in the everyday experience of isolated older adults.” (Ray, HealthLeaders, 8/25; Yu et al., Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 8/3)

Originally published at https://www.advisory.com.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (excerpt)

Cumulative loneliness and subsequent memory function and rate of decline among adults aged ≥50 in the United States, 1996 to 2016

Cumulative loneliness and memory aging in the US

Alzheimer Association

Xuexin Yu,Ashly C. Westrick,Lindsay C. Kobayashi

First published: 03 August 2022

ABSTRACT

Introduction

The study objective was to investigate the association between loneliness duration and memory function over a 20-year period.

Methods

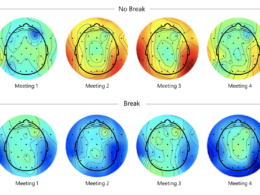

Data were from 9032 adults aged ≥50 in the Health and Retirement Study. Loneliness status (yes vs. no) was assessed biennially from 1996 to 2004 and its duration was categorized as never, 1 time point, 2 time points, and ≥3 time points. Episodic memory was assessed from 2004 to 2016 as a composite of immediate and delayed recall trials combined with proxy-reported memory. Mixed-effects linear regression models were fitted.

Results

A longer duration of loneliness was associated with lower memory scores (P < 0.001) and a faster rate of decline (P < 0.001). The association was stronger among adults aged ≥65 than those aged <65 (three-way interaction P = 0.013) and was stronger among women than men (three-way interaction P = 0.002).

Discussion

Cumulative loneliness may be a salient risk factor for accelerated memory aging, especially among women aged ≥65.

Highlight

- A longer duration of loneliness was associated with accelerated memory aging.

- The association was stronger among women than men and among older adults than the younger.

- Reducing loneliness in mid- to late life may help maintain memory function.

Background:

Loneliness is thought to be a modifiable psychosocial risk factor for poor cognitive health outcomes in later life, including increased risks of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD).1–8

As the subjective experience of social isolation, loneliness is theorized to be an adverse emotional state with the perception of unfulfilled personal and social needs.9

As the subjective experience of social isolation, loneliness is theorized to be an adverse emotional state with the perception of unfulfilled personal and social needs

The experience of loneliness could be persistent or time-varying, as it may be associated with individuals’ personal coping strategies to stressful life events,10 and its health effects may accumulate over time, leading to substantial heterogeneity in its putative effects on cognitive health.11

Although there exists rich evidence on the association between loneliness and cognitive health,1–8 most prior studies have measured loneliness at a single time point.6, 12, 13

Results using this approach may be subject to reverse causation: in addition to being a risk factor in its own right, loneliness could also be part of a preclinical syndrome of ADRD, whereby individuals may withdraw from their social networks due to early cognitive symptoms, and thus experience loneliness.7, 14–17

Results using this approach may be subject to reverse causation: in addition to being a risk factor in its own right, loneliness could also be part of a preclinical syndrome of ADRD, …

… whereby individuals may withdraw from their social networks due to early cognitive symptoms, and thus experience loneliness.

Although some studies have measured longitudinal loneliness trajectories over short periods of time18 or simultaneously with cognitive outcome trajectories,2, 17, 19 these short-term and synchronous measures of loneliness may not provide strong evidence regarding its temporality of association with cognitive outcomes.

Finally, it remains unclear whether the cumulative effect of loneliness on cognitive aging varies across the life span and sex identity, although existing research has observed that the health effects of loneliness and subjective social support were more exaggerated in later life compared to earlier in life, and were stronger among women than men.20,

… existing research has observed that the health effects of loneliness and subjective social support were more exaggerated in later life compared to earlier in life, and were stronger among women than men

Methodology and others

see the original publication

Discussion

In this population-based, prospective cohort of 9032 middle-aged and older adults in the United States, cumulative loneliness over an 8-year exposure period was associated with accelerated memory aging during the subsequent 12-year follow-up, indicating a dose–response relationship.

The observed association was modified by age and sex, suggesting that ameliorating loneliness status in mid- to late life may help delay memory aging, especially among women aged 65 and over.

Comparison to existing studies

Our findings are consistent with existing studies demonstrating the role of loneliness as a potential risk factor for cognitive aging.4, 17–19

This study contributes to the existing literature by measuring the duration of loneliness over a sustained mid- to late life period, thus providing additional support for a causal relationship.

Biological plausibility for the observed association is strong: the sustained experience of loneliness may induce emotional stress, anger, and anxiety,37 resulting in unhealthy coping behaviors such as alcohol consumption,38 physical inactivity,39 smoking,40 and sleep fragmentation,41 thus leading to increased risks of hypertension,42 stroke,43 heart disease,43 depressive symptoms,44 and amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition.45, 46

These are all important predictors of risks for dementias and accelerated cognitive aging among older adults.47, 48

Biological plausibility for the observed association is strong: the sustained experience of loneliness may induce emotional stress, anger, and anxiety, resulting in …

… unhealthy coping behaviors such as alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, smoking, and sleep fragmentation, …

.. thus leading to increased risks of hypertension, stroke, heart disease, depressive symptoms, and amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition.

Consistent with our second hypothesis, we found that the association of loneliness with memory aging was stronger among adults aged 65 and over than among those aged under 65.

This finding is in line with existing studies indicating that loneliness exacerbates age-related differences in evaluated systolic blood pressure and cardiovascular risk.49, 50

Notably, our findings are contradictory to existing research indicating that the association between loneliness and dementia risk becomes weaker in magnitude with older age.12

One potential explanation for this heterogeneity is that our study applied validated composite memory z-scores that ensured the inclusion of the most cognitively impaired older adults to minimize potential selection bias in our findings.29

However, these inconsistent findings may also indicate a domain-specific association between loneliness and cognitive function, which requires further investigation.

Our observed effect modification by sex is consistent with several studies demonstrating the effects of loneliness on mental health are greater among women than men.51, 52

Gender roles and social norms, such as the expectations and demands of social relationships where women tend to have larger and more multifaceted social networks than men, may make women less likely to feel lonely than men, but more vulnerable once experiencing cumulative loneliness.21, 23, 51, 52

However, existing studies focusing on the sex-specific association between loneliness and cognitive function have yielded inconsistent findings.12, 53

One prior population-based study in China found that the experience of loneliness was associated with a greater risk of dementia among men than women,53 while another study in the United States suggested no sex-specific effects of loneliness on global cognitive performance.12

The inconsistency between these findings and ours could be attributable to population differences in the effects of loneliness on cognitive aging, but could also be due to the use of different measures of loneliness exposure or systematic measurement error that may vary across populations whereby men may be more reluctant to admit loneliness than women due to fear of social stigma.54

Further research is warranted from diverse populations in which the cultural meaning and experience of loneliness and its subsequent effects on cognitive aging may vary.

Limitations and strengths

This study has limitations.

First, as we did not employ the three-item University of California Los Angeles loneliness scale because of limitations in its use in the 1992 to 2000 HRS datasets,55 our use of a single item to assess loneliness may result in measurement error.

However, this item has been validated as part of a larger depression scale and our use of repeated measures of loneliness over an 8-year period helps to minimize within-person variance in loneliness exposure.

Second, selection bias may exist as we required participants to survive and to have been retained in the HRS from 1996 through 2004 to have complete five-wave data on loneliness.

This may have led to our results underestimating the true magnitude of association, as older adults with a longer duration of loneliness and with lower memory function could be more likely to have died or dropped out of the study during the exposure period.

Third, there could be residual confounding by objective social isolation, as there is no single well-accepted measure of objective social isolation.

We incorporated multiple measures capturing different forms of social connections to measure and adjust for objective social isolation as best as possible.

Moreover, just over half of participants (54%) had missing values on at least one objective social isolation item and these values were imputed in later waves (1998 to 2004), possibly leading to over-adjustment and attenuation of estimates in Models 2 and 3.

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to measure cumulative duration of loneliness over an 8-year period in mid- to late life in relation to memory aging.

We investigated this association overall and by age and sex. The observed dose–response association between loneliness duration and memory aging indicates the potential for a biological link between the psychological experience of loneliness and memory function, which should be further investigated.

Our sensitivity analyses restricted to cognitively healthy individuals at baseline help to rule out reverse causation, adding support for a potential causal relationship to the literature on this topic.

Conclusion

In this population-based cohort study of middle-aged and older adults in the United States, cumulative duration of loneliness in mid- to late life may be a salient risk factor for accelerated memory aging, especially among women aged 65 and over.

Further research from diverse populations to investigate underlying biological mechanisms is warranted.

… cumulative duration of loneliness in mid- to late life may be a salient risk factor for accelerated memory aging, especially among women aged 65 and over.

Originally published at https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/

Alzheimer Association Journal

Xuexin Yu,Ashly C. Westrick,Lindsay C. Kobayashi

First published: 03 August 2022

Names mentioned

University of Michigan School of Public Health used data from the National Institute of Aging’s Health and Retirement

Xuexin Yu, one of the study’s authors.

Elena Portacolone, an associate professor of sociology at the Institute for Health and Aging at the University of California, San Francisco,