NEJM — New England Journal of Medicine

Jacqueline Baras Shreibati, M.D.

August 7, 2021

By April 2020, I was ready for video. The Covid-19 crisis required that patients, clinicians, and staff stay home, so clinics throughout the United States had ramped up their telehealth practices. The federally qualified health center (FQHC) where I work had spent several weeks thoughtfully developing the workflows for video visits. I was eager to virtually see my patients — mostly elderly, Spanish-speaking, and low income — and be a part of the digital health revolution.

When I started, I thought there was a hierarchy in which in-person care was the gold standard, video visits were second, and telephone visits the method of last resort.

But a year later, I don’t think of them as best, good, and OK. I see them as different — each ideal for different contexts.

And just as people with visual impairment may have heightened use of their other senses, my year of telephone care during the Covid-19 pandemic has cultivated my capacity to connect with patients solely through sound.

It took only a day or two to discover the benefits of video communication. A patient called in to say he had run out of one of his pills. He lived alone and didn’t understand the labels on his pill bottles.

Had he missed doses of his blood thinner or his vitamins?

During our video visit, he showed me the empty bottle, and I was able to promptly identify the needed medication and arrange for home delivery.

But video was not the norm for my telehealth practice in 2020, for a simple reason: more often than not, it was problematic for my patients.

- Many of them had basic phone plans with restricted data for video calls.

- Others struggled to set up the video platform on their phone or to find a private space to speak openly with me about their health.

We had set up the clinic to support video-conferencing technology, but the technology fell short of supporting patients with limited incomes, digital literacy, or housing.

The inequity in use of video technology for care during the Covid-19 pandemic is well documented: older, non-White, or uninsured patients were 40 to 60% less likely to use video visits than younger, White, or insured patients.1

It’s hard for patients to embrace digital health if their clinic does not have information-technology support or their clinicians don’t encourage them to try it.

- Aware of implicit bias, I told my patients about the public Wi-Fi program with outdoor access points on streetlight poles.

- I offered access to a language interpreter.

- I avoided reinforcing negative stereotypes in my notes (e.g., “patient declines video visit”).

But despite such efforts, my patients were choosing telephone over video visits.

I had to adapt and embrace this new reality. My patients needed to be heard.

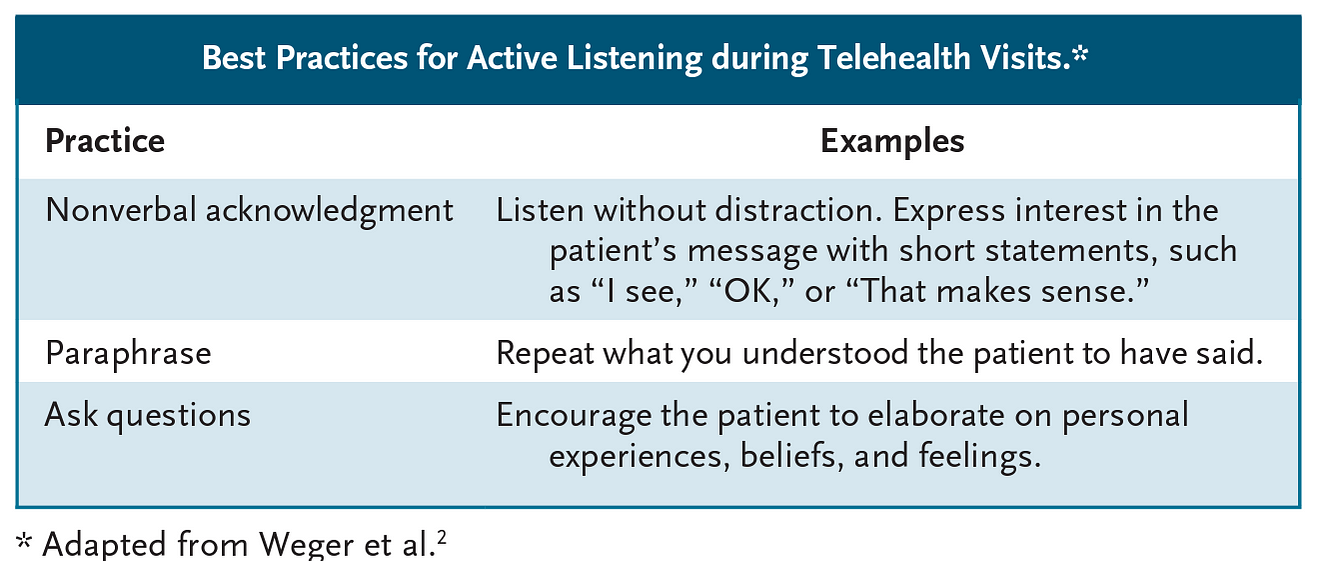

Best Practices for Active Listening during Telehealth Visits.

The first few months of telephone visits were punctuated by awkward pauses, but I gradually became more comfortable, even confident, with the silence.

Since I was unable to look at or touch a patient, the only “data” I had were words and tone of voice.

I became adept at active listening, listening for the intent and feeling in my patients’ voices. I paid attention to how my patients were telling their stories. I realized I had more to learn, and I read about what communication researchers have described as best practices (see table).2

While the telephone visit helped me become a better listener, there were also benefits for my patients.

When they couldn’t see my face or other visual distractions, some patients seemed more willing to confide in me about sensitive topics, such as drinking or smoking habits.

Admittedly, on some telephone visits, I felt like I was on the other side of a virtual confessional wall.

The flexible, on-the-go nature of a telephone visit also fit very well into my patients’ busy lives. Many of them, essential workers, would discreetly speak with me on their way to work or during a lunch break. During the summer and fall of 2020, I consistently had 0% no-shows for audio visits, because I was meeting my patients where they were.

My experience is consistent with data showing that telephone visits support high-quality care, particularly in primary care and community health settings.

- Since 2010, the Veterans Health Administration has incorporated scheduled telephone visits into their patient-centered medical home model to improve care access and efficiency, and such visits have proven beneficial when a physical exam is not required or when patients are anxious about facing a clinician.3

- A survey of 43 FQHCs in California revealed that telephone visits during the pandemic increased access to care, reduced wait times, and in certain circumstances, offered quality of care comparable to that of video visits.4

More evidence is needed to understand the situations in which telephone visits can effectively support specialty care, as in my cardiology clinic.

As I return to in-person clinic visits in 2021, I’ve reflected on my audio-only experiences from the past year.

I recently saw a woman in her 80s for follow-up for heart failure. In the 30 minutes we had together in clinic, most of the time was taken up by vital signs checks, medication reconciliation, and making sure she was wearing a properly fitted face mask.

I recall thinking that just a few months ago when we had been on the phone together, I had immediately jumped into asking her about lilacs, her latest gardening project.

Audio-only visits had provided a level of intimacy and candor that I realized I was losing “in person.” Yes, I was grateful to reconnect with her through the physical exam, but my laser focus on her story was slipping away. Was I actually nostalgic for the telephone visit?

Practicing medicine during a pandemic has indelibly changed my attitude toward audio-only communication.

- I now see the telephone as a useful tool for person-centered care.

- I offer my patients the option of telephone follow-up visits, and I look forward to the moments when I can chat with them on the phone between scheduled appointments.

- Audio-only care keeps me mindful of the humanity of medicine.

Outside the field of medicine, there is growing recognition of the profound personal connections that can be nurtured in audio-only environments.

The cofounder of Clubhouse, a popular voice-only social media app, has said, “Voice adds texture and fidelity to conversations that can be lacking in other venues. The intonation, inflection, and emotion that are conveyed through voice allow people to pick up on nuance and empathize with each other.”5

As a safety-net clinician, I couldn’t agree more. During a year marked by inequity and isolation, I learned how to listen and provide equitable and empathic care, thanks to the low-tech telephone.

Disclosure forms provided by the author are available at NEJM.org.

This article was published on August 7, 2021, at NEJM.org.

Author Affiliations

From Fair Oaks Health Center, Redwood City, and Google Health, Palo Alto — both in California.

Originally published at https://www.nejm.org.

PDF version

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/viewer.html?pdfurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nejm.org%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1056%2FNEJMp2104234%3FarticleTools%3Dtrue