This is a republication of the article below, under the title above, to provoke the discussion about the topics in other countries.

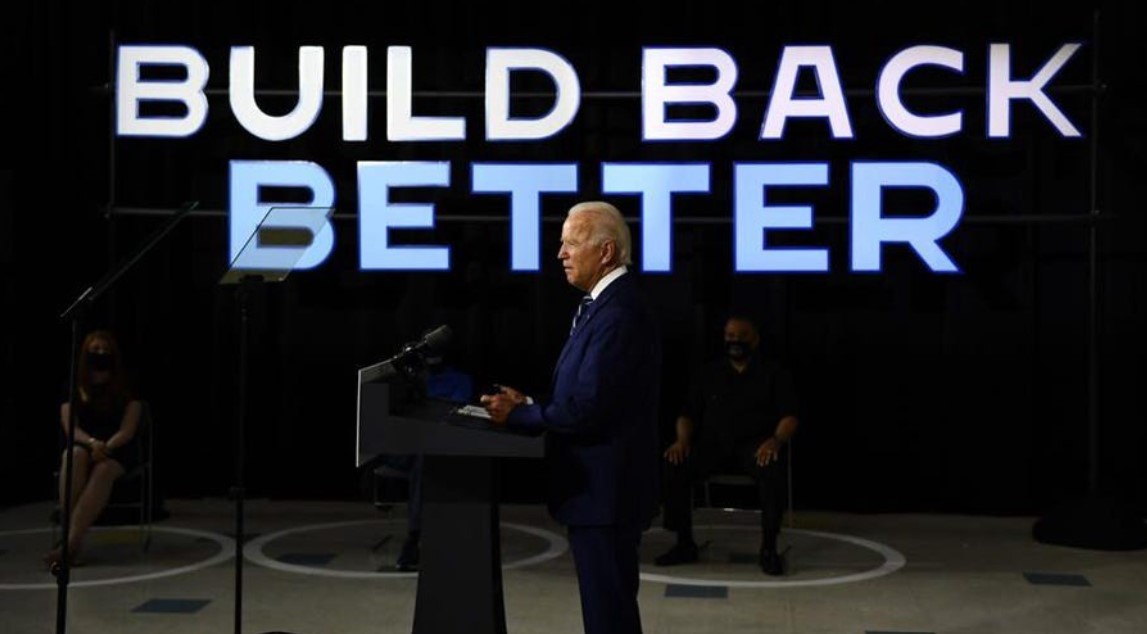

House Passes Build Back Better Act with Significant Health Care Provisions (USA)

American Hospital Association (ARA)

November 19, 2021

Key messages:

The House of Representatives today voted 220–213 to pass a modified version of the Build Back Better Act (H.R. 5376), a roughly $1.75 trillion social spending package that includes many health care provisions.

The bill, which is being considered under reconciliation procedures, is likely to undergo significant changes as it moves through the Senate in the coming weeks.

Among other provisions, the bill would:

- Expand access to coverage, including through a temporary coverage solution for individuals who fall into the Medicaid coverage gap and expansion of subsidized health insurance marketplace coverage;

- Penalize states that have not expanded Medicaid by reducing their federal Medicaid DSH allotment and limiting their use of uncompensated care pools;

- Authorize a number of programs to improve maternal and child health; and

- Make additional investments in workforce training, including education and loan repayment and expansion of Medicare-funded residency slots.

In statement shared with the media, AHA President and CEO Rick Pollack said, “The AHA supports many parts of the Build Back Better Act that would advance health in our nation’s communities.

These provisions include expanding access to coverage through subsidized health insurance marketplace plans and investing in workforce training.

In particular, we appreciate expansion of Medicare-funded physician residency slots and Pathway to Practice, which promotes physician diversity and improves access to physicians in communities dealing with sustained hardship. We also applaud the investments to improve maternal and child health.

“However, while we appreciate the goal of increasing coverage to residents in states that did not expand their Medicaid programs, it should not come at the expense of vital funding to hospitals and health systems located in those parts of the country that serve a large number of children, the poor, the disabled and the elderly. These cuts are unacceptable, especially while hospitals remain on the front lines of fighting COVID-19 and the deadly Delta variant.

“In addition, we are disappointed the House did not include critical funding for hospital infrastructure improvements through the Hill-Burton Act, as they did in an earlier version of the legislation.

“We look forward to working with the Senate to improve this bill.”

The House of Representatives today voted 220–213 to pass a modified version of the Build Back Better Act ( H.R. 5376), a roughly $1.75 trillion social spending package that includes many health care provisions. The bill, which is being considered under reconciliation procedures, is likely to undergo significant changes as it moves through the Senate in the coming weeks.

AHA Take

In a statement shared with the media today, AHA President and CEO Rick Pollack said, “The AHA supports many parts of the Build Back Better Act that would advance health in our nation’s communities. These provisions include expanding access to coverage though subsidized health insurance marketplace plans and investing in workforce training. In particular, we appreciate expansion of Medicare-funded physician residency slots and Pathway to Practice, which promotes physician diversity and improves access to physicians in communities dealing with sustained hardship. We also applaud the investments to improve maternal and child health.

“However, while we appreciate the goal of increasing coverage to residents in states that did not expand their Medicaid programs, it should not come at the expense of vital funding to hospitals and health systems located in those parts of the country that serve a large number of children, the poor, the disabled and the elderly. These cuts are unacceptable, especially while hospitals remain on the front lines of fighting COVID-19 and the deadly Delta variant.

“In addition, we are disappointed the House did not include critical funding for hospital infrastructure improvements through the Hill-Burton Act, as they did in an earlier version of the legislation.

“We look forward to working with the Senate to improve this bill.”

The following is a summary of key provisions affecting hospitals and health systems.

Health Care Coverage

Temporary Expansion of Marketplace Subsidies and Cost-Sharing Assistance to Address Coverage Gap in Non-Medicaid Expansion States

The legislation would temporarily close the Medicaid coverage gap by providing subsidized coverage through the federal health insurance marketplace for individuals with income under 138% of the federal poverty level. Beginning in 2023 and continuing through 2025, premium tax credits would be extended to such individuals to purchase marketplace coverage with zero dollar premiums (see section below) and cost-sharing assistance that reduces enrollee cost-sharing to 1%. Plans would be required to include non-emergency transportation and family planning benefits for this population and would be fully reimbursed by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS). Similar to the Medicaid program, enrollment in this Affordable Care Act (ACA) coverage expansion program would be available year round. Outreach and enrollment efforts would be funded during this period at $105 million. In addition, navigators to assist in enrollment would be funded through a combination of health plan user fees and appropriations.

Reductions in Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Allotment and Uncompensated Care Pools for Non-Medicaid-Expansion States

States that have not expanded their Medicaid program, including any state that chooses to reverse their Medicaid expansion, would face a reduction in their Medicaid DSH allotment. Beginning in fiscal year (FY) 2023, non-expansion states would be subject to a 12.5% reduction of their DSH allotment. This fixed 12.5% “DSH penalty” would be applied against their DSH allotment (allowing for inflation) each fiscal year the state has not expanded their program and would cease only if the state expands coverage. Note that the penalty also would apply to the state of Tennessee, which has its DSH allotment set in statute through FY 2025. The AHA estimates, based on available data, that the reduction in federal DSH spending for the non-expansion states would be $2.2 billion over five years and $4.7 billion over 10 years. Beginning in FY 2024, when the ACA DSH reduction delay is scheduled to end, the “DSH penalty” would be applied in addition to the ACA reduced DSH allotments for non-expansion states. Expansion states that decide to withdraw their coverage of the expansion population would be subject to DSH allotment reductions, and these reductions would be applied on a pro-rata basis.

Funding restrictions also would apply to any state with a Medicaid uncompensated care pool that has not expanded their program. Such restrictions would prevent these states from claiming federal matching dollars for health care services provided to an “expansion individual” through the pool funds. Non-expansion states with uncompensated care pools include Florida, Tennessee, Texas and Kansas.

Expanding Eligibility for and Value of Health Insurance Marketplace Subsidies

The legislation would extend the expanded eligibility for and value of health insurance marketplace subsidies authorized through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) through 2025. The subsidy expansion is currently authorized through 2022. Specifically, the ARPA expanded eligibility for subsidies to individuals above 400% of the federal poverty level (the limit in the ACA) by making eligible anyone for whom the cost of benchmark coverage would exceed 8.5% of income. The ARPA also lowered the premium percentage at every income level, with the effect of increasing the value of the marketplace subsidies and further reducing the cost of coverage. For individuals with income up to 150% of the federal poverty level, the new subsidy amounts result in the availability of plans with zero dollar premiums. This legislation also would expand marketplace cost-sharing assistance for certain low-income individuals and authorize funding for a state-based health insurance affordability fund (discussed below). It would not, however, address several other marketplace coverage issues, including fixing the “family glitch.”

Other, Related Health Insurance Marketplace Provisions

The legislation would establish a new health insurance affordability fund available to all states to provide assistance in reducing health care premiums and out-of-pocket costs through reinsurance programs, which would be funded at $10 billion annually from 2023 through 2025. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) also is directed to implement a temporary reinsurance program in non-Medicaid expansion states. In addition, cost-sharing reductions would be extended through 2025 for individuals with income up to 150% of the federal poverty level receiving unemployment.

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and Medicaid Coverage Improvements

Federal CHIP funding would be made permanent. In addition, other CHIP-related provisions would be made permanent, such as the pediatric quality measures program and the contingency fund to provide states with assistance in the event their CHIP state allotment is insufficient. States would be provided an option to increase CHIP income eligibility levels above the existing statutory ceiling, which is currently tied to Medicaid income levels. The bill also creates a drug rebate program similar to the Medicaid rebate program in order to lower the cost of prescription drugs for CHIP. The new rebate program strictly prohibits duplicate discounts for any drug purchased through the 340B program. In addition, children under the age of 19 will be provided one-year continuous eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP coverage. There also is Medicaid coverage available to justice-involved individuals 30 days prior to their release.

Ensuring Coverage for Pregnant and Postpartum Individuals

The legislation would require that Medicaid and CHIP provide 12 months of continuous postpartum coverage and provide the full range of Medicaid benefits during this period. Current rules generally permit enrollees to stay on Medicaid or CHIP for up to 60 days, though the ARPA provided states with an option, for five years, to extend Medicaid and CHIP eligibility to pregnant individuals for 12 months postpartum. The legislation also allows for a state option to provide coordinated care through a maternal health home for pregnant and postpartum individuals and provides $5 million in funding.

Expanding Medicare Benefits

The package includes a provision to expand Medicare coverage to include hearing benefits in 2023. The hearing benefits would cover hearing aids and aural rehabilitation, among other services. The traditional Medicare program does not cover such benefits; however, some Medicare Advantage plans do cover hearing services as supplemental benefits.

Other Medicaid Provisions

Enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentages (FMAP) Increase for Expansion States

The federal match for spending on the Medicaid expansion population would be increased by 3 percentage points from the current 90% FMAP to 93% FMAP. This would apply to all states that cover the Medicaid expansion population. The increased FMAP would apply for calendar quarters in 2023 through 2025.

Phase-out of Temporary FMAP Increase from the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA)

The temporary FMAP increase of 6.2 percentage points established by the FFCRA to assist states during the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) would be phased out beginning March 31, 2022, rather than the end of the quarter in which the PHE ends, as previously established. The FMAP increase would be reduced to 3 percentage points on April 1, 2022, 1.5 percentage points on July 1, 2022 and end entirely on Sept. 30, 2022.

PHE-related Eligibility Maintenance of Effort

States would need to maintain their Medicaid eligibility standards that were in place prior to the PHE. Should a state change eligibility requirements between Sept. 1, 2022, and Dec. 31, 2025, the state would be subject to a penalty that would reduce FMAP by 3.1 percentage points for each calendar quarter they have in place the more restrictive standards, methodologies or procedures, as compared to what was in effect on Oct. 1, 2021.

Medicaid Cap Amounts and the FMAP for the Territories

The legislation would permanently increase federal Medicaid funding for the territories by establishing a set FMAP of 83%.

Medicaid Pharmacy Payments

Requires that the HHS Secretary conduct a survey of retail community pharmacy drug prices in all states and the District of Columbia to determine the national average drug acquisition cost for covered outpatient drugs in the Medicaid program. Information to be collected includes the actual acquisition cost of the covered outpatient drugs, discounts and rebates, average professional dispensing fees paid, and reimbursement received from all sources of payment. Any pharmacy that receives a Medicaid payment must participate in the survey or risk civil monetary penalties not to exceed $10,000 for each day the survey data is not provided. The information collected would be made publicly available.

Other Health Care-related Provisions

Graduate Medical Education

The bill would increase the existing cap on the number of Medicare-funded residency slots by 4,000, with no more than 2,000 slots distributed each year starting in FY 2025. At least 25% of these slots would be awarded for primary care residencies, including obstetrics and gynecology, and at least 15% would be awarded for psychiatry residencies, including addiction medicine. To be eligible for these slots, hospitals must be training above their Medicare caps, located in a rural area, in states with new medical schools, located in or serving health professional shortage areas, or in states with the lowest quartile of medical resident to population ratio.

The bill also would establish the Rural and Underserved Pathway to Practice Program, which would provide 1,000 scholarships annually to students from underrepresented groups to attend post-baccalaureate programs and medical school, starting in FY 2023. Teaching hospitals would be eligible to train graduates of the Pathway to Practice Program, and these positions would be excluded from hospitals’ GME caps. Eligible teaching hospitals must be recognized by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education as providing mentorship, training in cultural and structural competency, and training in underserved areas.

The package also would provide $200 million for the Children’s Hospitals Graduate Medical Education program for FY 2022.

Maternal and Child Health

In addition to the expanded coverage for pregnant and postpartum individuals described above, the legislation would fund numerous maternal and child health initiatives, some of which were part of the AHA-supported Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act.

Among the funding allocations are:

- $100 million to address social determinants of maternal health;

- $75 million for the Office of Minority Health to award grants to community-based organizations operating in areas with high rates of adverse maternal health outcomes;

- $170 million to grow and diversify the perinatal nursing workforce;

- $50 million to support perinatal quality collaboratives;

- $50 million to help develop and diversify the doula workforce;

- $175 million to address maternal mental health conditions and substance use disorders;

- $85 million to support the development and integration of education and training programs for identifying and addressing risks associated with climate change for pregnant, lactating or postpartum individuals;

- $50 million for minority-serving institutions to study maternal mortality, severe maternal morbidity and maternal health outcomes;

- $25 million to identify Maternity Care Health Professional Target Areas; $50 million to promote community engagement in maternal mortality review committees and increase the diversity of a committee’s membership;

- $100 million for conducting surveillance for emerging threats to mothers and babies;

- $30 million for carrying out the Enhancing Reviews and Surveillance to Eliminate Maternal Mortality program;

- $15 million for the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System;

- $15 million for the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development;

- $30 million to evaluate, develop and expand the use of technology-enabled collaborative learning and capacity building models;

- $30 million to increase access to digital tools related to maternal health care; and $50 million for anti-discrimination and -bias training.

Behavioral Health

The bill includes a number of provisions to increase access to behavioral health services, including

- $40 million for behavioral health needs of family caregivers and

- $25 million for initiatives to address the behavioral health needs of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

It also expands the Community Mental Health Services Demonstration Program and makes permanent the option for states to provide mobile crisis intervention services.

Proposals to Lower Drug Costs

The package includes a number of proposals aimed at reducing the cost of prescription drugs.

It would direct the HHS to establish a Drug Negotiation Program, which would require the HHS Secretary to identify 100 brand-named, single-source drugs annually.

Beginning in 2025, the HHS Secretary must negotiate the price of 10 drugs from that list, followed by 15 drugs in 2026 and 2027, and 20 drugs annually thereafter.

In addition, insulin products must be included in negotiations. Certain drugs would be exempt from negotiation requirements based on exclusivity and expenditure criteria. Once a drug is selected for negotiation, it will remain in the program until a competitor product enters the market. The prices resulting from these negotiations would apply to individuals eligible for the program through Medicare Part B and Part D, as well as Medicare Advantage plans.

The legislation would establish penalties on manufacturers for certain actions. Failure for a drug manufacturer to negotiate the price of a selected drug would result in an excise tax. The legislation also would penalize drug manufacturers that increase their prices faster than inflation for drugs used by individuals covered by Medicare by requiring that the manufacturer pay a rebate to the federal government and subjecting manufacturers to a civil monetary penalty if they fail to pay the rebate.<.p>

Other provisions would redesign the Medicare Part D program by capping beneficiary out-of-pocket costs and shifting certain financial responsibilities to insurers and drug manufacturers. The legislation also would repeal a final rule aimed at creating a new safe harbor protection for pharmacy benefit managers.

Finally, the bill would establish a $35 cap on cost-sharing for insulin products under Medicare Part D, apply zero coinsurance to vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices under Medicare Part D and revise payment for new biosimilar products under Medicare Part B.

Addressing Disparities

The bill also would provide $75 million to increase research capacity at minority-serving institutions, diversify the national scientific workforce and expand the activities of the National Institutes of Health Scientific Workforce Diversity Office.

Investments in Clean Energy and Sustainability Efforts

The bill includes significant funding for investments in clean energy and sustainability programs that have the potential to benefit hospitals and health systems and the communities they serve.

For example, the bill includes

- $29 billion for a greenhouse gas reduction fund,

- with 40% of investment going to low-income and underserved communities;

- a $1 billion investment electric vehicle infrastructure;

- and $20 billion in clean energy innovation and climate pollution reduction investments.

Home- and Community-Based Services

The legislation includes $150 billion in investments in home- and community-based services, including through increasing provider reimbursement rates, making permanent the Money Follows the Person and the spousal impoverishment programs, and providing additional funding for states for home- and community-based care infrastructure investments.

Public Health Provisions

Pandemic Preparedness

The package contains a number of provisions to bolster the nation’s pandemic preparedness, including $1.4 billion for Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) laboratory activities to support renovation, improvement expansion and modernization of state and local public health laboratories and CDC laboratory infrastructure and enhancement of the CDC’s ability to oversee the biosafety and biosecurity of state and local public health laboratories.

It also provides $1.3 billion for the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) public health and preparedness research, development and countermeasure capacity, including improved support for surge capacity for facilities needed to respond to a public health emergency and for drugs, devices, shoring up the Strategic National Stockpile, strengthening the supply chains, supporting domestic and global manufacturing of vaccines, bolstering biosecurity, and investing in therapeutics.

Finally it provides $300 million for modernizing the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) technological and laboratory infrastructure and innovation and enhancing food and medical product safety.

Public Health Infrastructure

The legislation includes provisions to improve the nation’s public health infrastructure, including

- $7 billion in funding for state, local and territorial public health infrastructure and programs;

- $2 billion for capital investments in health centers;

- and a number of provisions to improve the clinical workforce capacity (many of which are outlined in the following section).

Workforce

Workforce Capacity

The legislation includes several provisions intended to bolster health care workforce capacity and training in addition to several already noted above. These include:

- Reauthorizing the Health Profession Opportunity Grant (HPOG) Program, which provides grants for the purpose of preparing certain low-income individuals to enter into the health care profession.

- $2 billion for the National Health Service Corps, which provides scholarships and loan repayment to qualified health care providers in exchange for service in underserved parts of the country.

- $500 million for the Nurse Corps, which provides loan repayment assistance to registered nurses (RNs) and advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) in exchange for service in critical shortage areas or serving as faculty at eligible nursing schools.

- $500 million for schools of nursing in underserved areas.

- $500 million for schools of medicine in underserved areas, with priority given to minority-serving institutions.

- $85 million across several programs aimed at bolstering training and education for palliative care medicine and nursing.

Nurse Staffing Ratios for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs)

The legislation would establish staffing-related requirements on SNFs. Specifically, it would establish a requirement for SNFs to use the services of a RN 24 hours a day, seven days a week beginning Oct. 1, 2024, subject to existing statutory waivers. In addition, the legislation directs CMS to establish and enforce minimum ratios of staff-to residents in SNFs. These ratios would be informed by mandatory reports to Congress on the appropriateness of establishing minimum staffing ratios, the first of which must be completed within three years of enactment, and thereafter updated at least every five years. The HHS Secretary would be expected to promulgate regulations establishing minimum staffing ratios within a year of the first report to Congress. The HHS Secretary would have the authority to waive compliance with the minimum staffing ratio for SNFs in rural areas with an insufficient workforce supply.

Paid Family and Medical Leave

The legislation would establish the first permanent, mandatory paid family and medical leave provision in federal law. The provision would require employers to provide up to four weeks of paid family and medical leave to cover a number of situations, including maternity and paternity leave and caring for ill or injured loved ones. The policy would begin in 2024, and would provide most workers, including contract, part-time and self-employed workers, with a minimum wage guarantee based on a portion of their income capped at $2,000 in 2024, and subsequently indexed to the annual Social Security Average Wage Index. This minimum standard benefit would provide funding by the federal government. States with existing programs would be eligible for funding from the federal government to maintain their programs. A similar provision is included to compensate employers that already provide such benefits.

Child Care Investments

The legislation includes a number of provisions to support access to child care. It would extend the child care tax credits provided for in the ARPA, create a tax credit for caregivers, establish new tools to connect parents and caretakers to child care, and create grants to improve safety in child care sites, among other provisions.

Community Violence and Trauma Intervention

The bill funds grants in the amount of $2.5 billion for public health-based interventions to address community violence and trauma. Grants will be awarded through the CDC, and communities with high rates of, and prevalence of risk factors associated with, violence-related injuries and deaths will be prioritized. Hospital-based violence intervention programs and trauma-informed mental health care and counseling are among the programs eligible for these grants.

Civil Monetary Penalties

The legislation dramatically increases certain civil monetary penalties for various violations of labor law. Any employer that commits an unfair labor practice as defined in section 8(a) of the National Labor Relations Act would be subject to civil monetary penalties of up to $50,000 for each violation. Any civil monetary penalties would be in addition to any other remedy the National Labor Relations Board (The Board) orders in the case. Where unfair labor practice is the result of discrimination on the basis of union membership or retaliation against an employee or has resulted in discharge of the employee or serious economic harm to the employee, The Board would double the fine imposed (up to a maximum of $100,000) in any case where within the past five years that employer has committed another unfair labor practice of that same type.

In determining the amount of the civil monetary penalty, The Board would need to consider a number of factors: (1) the gravity of the employer’s action that resulted in the penalty, including the impact on the party making the charge or any other person seeking to exercise rights guaranteed by the Act; (2) the size of the employer; (3) the history of previous unfair labor practices or other actions by the employer resulting in a penalty; and (4) the public interest. In addition, if The Board determines, based on the particular facts and circumstance involved, that a director’s or officer’s personal liability is warranted, a civil monetary penalty also may be assessed against the officer or director who directed or committed the violation, established the policy that led to the violation, or had actual or constructive knowledge of and authority to prevent the violation and failed to act.

Provisions Not Included in the Build Back Better Act

The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act

The bill does not contain the PRO Act, which would make sweeping changes to the National Labor Relations Act and other labor laws in the United States, including in ways that could have a significant adverse impact on hospitals and health systems as employers.

Hospital Infrastructure Funding under the Hill-Burton Act

The bill does not include the $10 billion in hospital infrastructure investment included in previous versions of the bill.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

Originally published at https://www.aha.org.