Report of the G20 High Level Independent Panel on Financing the Global Commons for Pandemic Preparedness and Response

Pandemic Financing

Tharman Shanmugaratnam; Lawrence Summers; Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala;

Ana Botín; Mohamed El-Erian; Jacob Frenkel; Rebeca Grynspan; Naoko Ishii; Michael Kremer; Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw; Luis Alberto Moreno; Lucrezia Reichlin; John-Arne Røttinge; Vera Songwe; Mark Suzman; Tidjane Thiam; Jean-Claude Trichet; Ngaire Woods; Zhu Min; Masood Ahmed; Guntram Wolff; Victor Dzau (Advisor); Jeremy Farrar (Advisor)

June 2021

We are in an age of pandemics. COVID-19 has painfully reminded us of what SARS, Ebola, MERS and H1N1 had made clear, and which scientists have repeatedly warned of: without greatly strengthened proactive strategies, global health threats will emerge more often, spread more rapidly, take more lives, disrupt more livelihoods, and impact the world more greatly than before.

Together with climate change, countering the existential threat of deadly and costly pandemics must be the human security issue of our times. There is every likelihood that the next pandemic will come within a decade — arising from a novel influenza strain, another coronavirus, or one of several other dangerous pathogens. Its impact on human health and the global economy could be even more profound than that of COVID-19.

The world is nowhere near the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Without urgent and concerted actions and significant additional funding to accelerate global vaccination coverage, the emergence of more variants of the virus is likely and will continue to pose a risk to every country. The solutions for vaccinating the majority of the world’s population are available and can be implemented within the next 12 months. More decisive political commitments and timely follow-through will resolve this disastrous global crisis.

The world is also far from equipped to prevent or stop the next pandemic. Lessons from COVID-19, on how the world failed to prevent the pandemic, why it has been prolonged at such catastrophic cost, and how we can overcome the crisis if we now respond more forcefully, provide important building blocks for the future. We must use this moment to take the bold steps needed to avoid the next pandemic, and not allow exhaustion from current efforts to divert attention from the very real risks ahead.

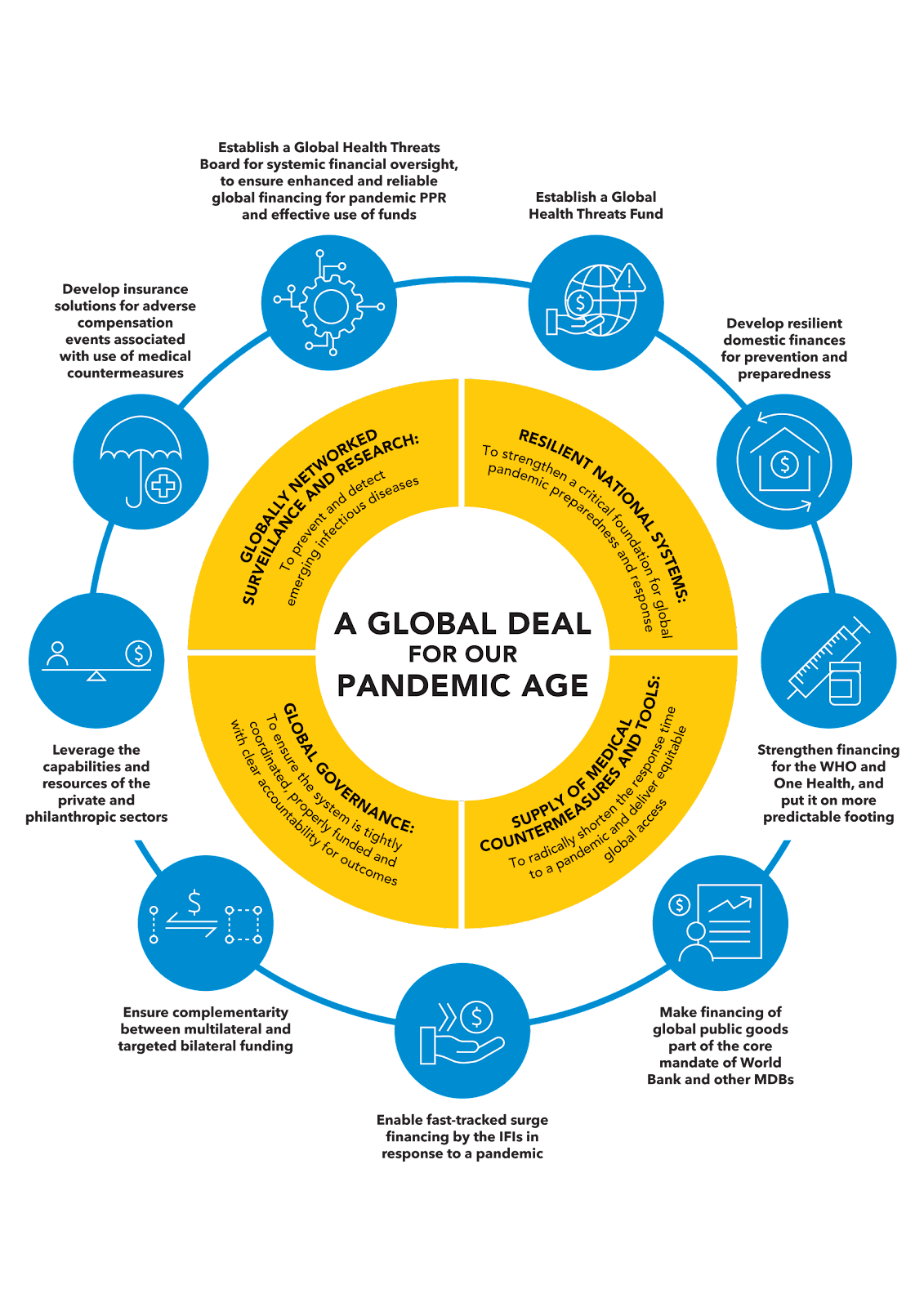

Plugging Four Major Gaps

Making the world safer requires stepped-up and sustained national, regional and global actions and coordination, leveraging fully the private sector, to prevent outbreaks as well as to respond much faster, more equitably and more effectively when a pandemic emerges. We must plug four major gaps in pandemic prevention, preparedness and response:

- Globally networked surveillance and research: to prevent and detect emerging infectious diseases

- Resilient national systems: to strengthen a critical foundation for global pandemic preparedness and response

- Supply of medical countermeasures and tools: to radically shorten the response time to a pandemic and deliver equitable global access

- Global governance: to ensure the system is tightly coordinated, properly funded and with clear accountability for outcomes

Investing in Global Public Goods: To Save Immense Costs

We can only avoid future pandemics if we invest substantially more than we have been willing to spend in the past, and which the world is now paying for many times over in dealing with COVID-19’s damage.

Countries must step up domestic investments in the core capacities needed to prevent and contain future pandemics, in accordance with the International Health Regulations. Governments will in many cases have to embark on reforms to mobilize and sustain additional domestic resources, so as to build up these pandemic-related capacities and strengthen public health systems more broadly, while at the same time enabling their economies to return to durable growth. Low- and middle-income countries will need to add about 1% of GDP to public spending on health over the next five years.

However, domestic actions alone will not prevent the next pandemic. Governments must collectively commit to increasing international financing for pandemic prevention and preparedness by at least US$75 billion over the next five years, or US$15 billion each year, with sustained investments in subsequent years.

The Panel assesses this to be the absolute minimum in new international investments required in the global public goods that are at the core of effective pandemic prevention and preparedness. The estimate excludes other investments that will contribute to resilience against future pandemics while benefiting countries in normal times. These complementary interventions — such as containing antimicrobial resistance, which alone will cost about US$9 billion annually, and building stronger and more inclusive national health and delivery systems — provide continuous value. Furthermore, the estimated minimum international investments are based on conservative assumptions on the scale of vaccine manufacturing capacity required in advance of a pandemic. Larger public investments to enable enhanced manufacturing capacity will indeed yield much higher returns.

The minimum additional US$15 billion per year in international financing for pandemic preparedness is still a significant increase. It is a critical reset to a dangerously underfunded system.

These investments are a matter of financial responsibility, besides being a scientific and moral imperative. They will materially reduce the risk of events whose costs to government budgets alone are 700 times as large as the additional international investments per year that we propose, and 300 times as large as the total additional investments if we also take into account the domestic spending necessary. The full damage of another major pandemic, with its toll on lives and livelihoods, will be vastly larger.

Crucially, this additional international funding must add to, and not substitute for, existing support to advance global public health and development goals. It would be short-sighted to scale up efforts for pandemic prevention and preparedness by reallocating multilateral or bilateral Official Development Assistance (ODA) resources from other development priorities, particularly given the likely lasting negative impacts of the current pandemic on economic and human development in low- and lower-middle-income countries. The threat of pandemics to our collective security warrants a new and more sustainable global financing approach, beyond traditional aid, to invest in global public goods from which all nations benefit.

Strengthening Global Governance of Health and Finance

However, money alone will not deliver a safer world without stronger governance. The current global health architecture is not fit-for-purpose to prevent a major pandemic, nor to respond with speed and force when a pandemic threat emerges. As the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board highlights, the system is fragmented and complex, and lacks accountability and oversight of financing of pandemic preparedness. We must address this by establishing a governance mechanism that integrates the key players in the global health security and financing ecosystem, with the World Health Organization (WHO) at the center.

To plug this gap, we propose establishing a new Global Health Threats Board (Board). The proposal builds loosely on the model of the Financial Stability Board, established by the G20 in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and which has operated successfully as a collective to contain risks to the global financial system.

This new governance mechanism will bring together the worlds of health and finance. The Board should include Health and Finance Ministers from a G20+ group of countries and heads of major regional organizations, with leadership and membership that ensures credibility and inclusivity. It should have a permanent, independent Secretariat, drawing on the resources of the WHO and other multilateral organizations.

This new Board will complement the Heads of State/Heads of Government-level Global Health Threats Council that has been proposed by the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPPR), to be established by the UN General Assembly. The Panel supports the establishment of this top-level political leadership council, to mobilize the strong collective commitment required for global health security. The Board, on the other hand, will aim more specifically to match tightly networked global health governance with financing, which are both critical enablers to reduce pandemic risks. It should take reference from the initiatives and work of the proposed Global Health Threats Council, to ensure a complementarity of functions.

The Board would provide systemic financial oversight aimed at enabling proper and timely resourcing of capacities to detect, prevent and rapidly respond to another pandemic, and to ensure the most effective use of funds. It must join up the efforts of international bodies, with clearly delineated responsibilities that match their comparative strengths, and ensure that the system fully engages and leverages the capabilities of the private sector and non-state actors. The Board must also track global risks and outcomes, and ensure every country plays its part to enhance global health security.

The Key Strategic Moves

A transformed system, with stronger global financial governance, will require both greater resources for existing institutions, with enhanced mandates where necessary, and a new multilateral funding mechanism that will plug the major gaps in global public goods needed to reduce pandemic risks. We must make four strategic moves.

- First, nations must commit to a new base of multilateral funding for global health security based on pre-agreed and equitable contribution shares by advanced and developing countries.

- Second, global public goods must be made part of the core mandate of the International Financial Institutions (IFIs) — namely the World Bank and other multilateral development banks (MDBs), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

- Third, a Global Health Threats Fund mobilizing US$10 billion per year should be established, and funded by nations based on pre-agreed contributions.

First, nations must commit to a new base of multilateral funding for global health security based on pre-agreed and equitable contribution shares by advanced and developing countries. This will ensure more reliable and continuous financing, so the world can act proactively to avert future pandemics, and not merely respond at great cost each time a new pandemic strikes.

This must include a fundamentally new way of financing a reformed and strengthened WHO, so that it receives both enhanced and more predictable resources. The Panel joins the call by the IPPPR for assessed contributions to be increased from one-quarter to two-thirds of the budget for the WHO’s base program, which will effectively mean an addition of about US$1 billion per year in such contributions.

Second, global public goods must be made part of the core mandate of the International Financial Institutions (IFIs) — namely the World Bank and other multilateral development banks (MDBs), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). They should draw first on their existing financial resources, but shareholders must support timely and appropriately sized replenishments of their concessional windows and capital replenishments over time to ensure that the greater focus on global public goods is not at the expense of poverty reduction and shared prosperity.

The IFIs are a potent but vastly under-utilized tool in the world’s fight against pandemics and climate change. The MDBs should partner with countries to incentivize and increase investments in pandemic preparedness and accelerate closing of critical health security gaps. This will require enhancing the grant element of their funding through dedicated concessional windows for pandemic preparedness. In this, they should partner with the grant-based global health intermediaries including Gavi and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, to leverage each other’s funding for investments that will strengthen health system resilience.

The IFIs should also provide swift, scaled-up access to funds in response to a pandemic, with relaxed rules on country borrowing and automatic access for pre-qualified countries. This should entail new or strengthened pandemic windows in the IMF and MDBs, and the authorization for MDBs to access additional market funding at the onset of a pandemic to finance a scaled-up response. To ensure that these official funds are used to counter the impact of the pandemic, the IMF, working with the relevant stakeholders, should propose a framework of pre-established rules for relief on debt servicing that involves the participation of all creditors in restructurings instituted in future pandemics.

Third, a Global Health Threats Fund mobilizing US$10 billion per year should be established, and funded by nations based on pre-agreed contributions. This new Fund, at two-thirds of the minimum of US$15 billion in additional international resources required, brings three necessary features into the financing of global health security. First, together with an enhanced multilateral component of funding for the WHO, it would provide a stronger and more predictable layer of financing. Second, it would enable effective and agile deployment of funds across international and regional institutions and networks, to plug gaps swiftly and meet evolving priorities in pandemic prevention and preparedness. Third, it would also serve to catalyze investments by governments and the private and philanthropic sectors into the broader global health system, for example through matching grants and co-investments. The Fund’s functions should be defined to ensure that it complements rather than substitutes for financing of the MDBs’ concessional windows and the existing global health organizations.

The new Fund should support the following major global actions:

- Building a transformed global network for surveillance of infectious disease threats. This will require a major scale-up of the network, combining pre-existing and new nodes of expertise at the global, regional and country levels, with the WHO at the center.

- Providing stronger grant financing to complement MDBs’ and the global health intermediaries’ support for country- and regional-level investments in global public goods.

- Ensuring enhanced and reliable funding to enable public-private partnerships for global-scale supply of medical countermeasures, so we can preclude severe shortages anywhere and avoid prolonging a pandemic everywhere. This added layer of funding will support a permanent network to drive end-to-end global supply, which builds on the lessons learned from the ACT-Accelerator coalition.

- Supporting research and breakthrough innovations that can achieve transformational change in efforts to prevent and contain future pandemics, complementing existing R&D funding mechanisms like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).

The Fund will be structured as a Financial Intermediary Fund (FIF) at the World Bank, which will perform the treasury functions, similar to how it hosts other international arrangements like the Global Environment Facility. Governance of the Fund will be independent of the World Bank, under an Investment Board, which could also be constituted as a committee of the Global Health Threats Board, which will determine the priorities and gaps to be addressed by the Fund.

Fourth, multilateral efforts should leverage and tighten coordination with bilateral ODA, and with the private and philanthropic sectors. Better coordination within country and regional platforms will have greater impact in reducing pandemic risks, and enable better integration with ongoing efforts to tackle endemic diseases and develop other critical healthcare capabilities. It will be important to ensure that ODA flows mobilized for pandemic preparedness add to and do not divert resources from other priority development needs.

There is significant scope for governments and the MDBs to mobilize private sector resources for pandemic preparedness and response, especially in developing global-scale capacity for critically-needed supplies, from testing kits and vaccines to oxygen cylinders and concentrators, as well as the whole delivery infrastructure needed within countries. The public sector should also grow partnerships with philanthropic foundations to substantially expand research on infectious disease threats and breakthrough countermeasures. This could include efforts to de-risk early-stage R&D and other high-risk investments, in order to attract private institutional investors.

Significant progress is within reach in the next five years. Strong and sustained political commitment, a recognition of the mutual interests of nations in health security, and long-term financing will be essential.

The collective investments we propose, with equitable contributions by all nations, are affordable. They are also miniscule compared to the US$10 trillion that governments have already incurred in the COVID-19 crisis.

We must invest without delay. It will be a huge error to economize over the short term and wait once again until it is too late to prevent a pandemic from overwhelming us. The next pandemic may indeed be worse.

Originally published at https://pandemic-financing.org.

PDF version