The previously reported nursing shortage of 6 million could double to 12 million over coming years.

Health Policy Watch

Howard Catton

11/03/2022

Howard Catton, a registered nurse, is the Chief Executive Officer of the International Council of Nurses, a federation of more than 130 National Nursing Associations worldwide.

Personal protective equipment was essential to protect healthcare workers during the pandemic

Key messages

by Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Chief Editor of The Digital Health — Strategy Blog

March 11, 2022

Pandemic happened during pre-existing health workforce crisis

- Before the storm , there was a shortage of six million nurses — mainly in poorer countries.

- The pandemic revealed how weakened our health systems had become, due to under investments in the people who are the system’s backbone.

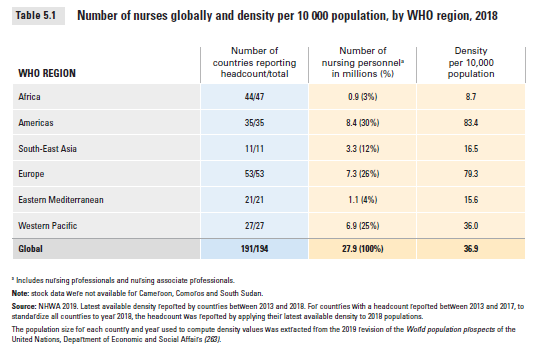

- Among some 27.9 million nurses worldwide, there were also huge inequalities in the number of nurses per capita in different nations of the world, ranging from

– 8.7 nurses per 10,000 people in WHO’s Africa region to

– 83.4 in the Americas.

– Nine out of ten were women.

The SOWN report called for massive investment in nurse education, jobs and leadership,

so as to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the health-related aspects of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) .

- The report also called for a programme of strategic investment in nurses to correct decades of complacency about workforce planning, which has always been too short-term, most often tied to government election cycles of four or five years.

- It concluded that such investment, continued over a much longer period, would also lead to more advancement in education, gender equality, the provision of decent work, and economic growth.

But when the pandemic hit, those longer-term strategies and plans were once again put aside.

Unsurprisingly, the pandemic has taken a dreadful toll on the nursing workforce.

- It has driven up demand for nurses, who are the critical “front line” health professionals, whilst

- at the same time cutting across nurse supply due to infection, increased absences — and thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, COVID-related deaths.

- … in the most recent survey (2021) of some 5000 nurses and nurse managers, 11% said they intended to leave their position soon, with proportions much higher among the most senior nurses.

The previously reported nursing shortage of 6 million could double to 12 million over coming years.

- ICN now believes that, with a further four million nurses planning to retire by 2030, and the as yet unclear and untold toll of what we are calling the COVID Effect on nursing numbers, the previously reported nursing shortage of 6 million could double to 12 million over coming years.

- In addition, nurses are experiencing increased mental health problems, as the intensity of their work has resulted in anxiety, stress and burnout.

- All of that has been exacerbated by more frequent experiences with death, and in nurses having to take the place of family members and friends holding the hands of patients who would otherwise have died alone.

- On top of this, moral injuries, which result from nurses being required to make or witness ethically challenging decisions about patient care delivery, also are on the rise.

But, there is a brighter side of the crisis

- But while all this was happening, there was one small chink of brightness in all the gloom: the pandemic did lead to greater public and policymaker awareness of nurses essential function, and the value they provide to the societies they serve.

- While many burnt-out nurses may be leaving the professions, younger groups are still entering the vocation — sometimes even more than before.

- But unless the global nursing workforce is brought up to full strength, even when the pandemic is finally over, grand plans about ‘healthcare for all’ will be nothing more than pipe dreams.

Preparing for the next pandemic — workforce investments

- Investment in nursing capacity is also critical in preparing for future epidemic and pandemic risks.

The report provides a blueprint for what is needed now. That is:

- a decade-long, fully-funded global investment plan to bring the nursing workforce up to its required global size and strength —

- while correcting existing imbalances between countries in nursing staff, per capita.

- This means better planning by governments about their nursing needs, based on concrete projections of requirements of health systems with a clear strategy to meet those needs, without relying on mass recruitment from low and middle-income countries to end the brain drain of nurses from LMICs.

- ICN realizes this will be a tough call economically for governments, not least because of the financial effects of the pandemic, but it is necessary.

- We think that low- and middle-income ‘donor’ countries should be compensated for losing their much-needed nurses.

Nurses at the policymaking table

- Finally, another critical element of a more forward-looking strategy is the greater inclusion of nurses — 90% of whom are women — in decision-making circles.

- Having nurses working in advanced roles, and services based on nurse-led models of care, are the keys to the brighter future we all deserve.

Health and peace are inseparable

- Fast forward to 24 February 2022. We can anticipate that the recent outbreak of war in Ukraine will only compound the challenges seen during the past two years of the pandemic with strapped healthcare services, and insufficient investment in nursing services.

- And whenever I hear governments say they can’t afford to invest in their nurses? I say, they can’t afford not to invest.

FULL VERSION (Of the original article)

At Pandemic’s Two Year Milestone: More Investment In The World’s Nurses Is Needed — Now

The previously reported nursing shortage of 6 million could double to 12 million over coming years.

Health Policy Watch

Howard Catton

11/03/2022

The applause has long ceased — while the ongoing pressures of the pandemic have left long-term scars on the physical, moral and mental health of the world’s nurses.

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, governments need to offer better solutions.

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic, and the world held its breath.

As COVID-19 swept the world, people in many major cities demonstrated their gratitude for healthcare workers with public shows of support, clapping and cheering for the heroism of nurses and their colleagues, the first responders to the surge in cases of a new and often deadly disease.

But while the applause has long ceased, and more recently replaced by public protests against restrictions, the pandemic continues. And so does the work of the global nursing workforce in tackling it.

But while the applause has long ceased, and more recently replaced by public protests against restrictions, the pandemic continues. And so does the work of the global nursing workforce in tackling it.

Table of Contents (TOC)

- Pandemic happened during pre-existing health workforce crisis

- Before the storm — shortage of six million nurses

- Inequalities income-driven

- When the storm hit

- Dreadful toll

- Brighter side of the crisis

- Preparing for the next pandemic — workforce investments

- Nursing “offset credits” to countries that provide nurses

- Nurses at the policymaking table

- Health and peace are inseparable

Pandemic happened during pre-existing health workforce crisis

Already at the start, the world was in the midst of a global healthcare crisis. Decisions made in the previous decade had led to a fragile nursing workforce with dire shortages in many countries that were already putting public health at risk.

The pandemic revealed how weakened our health systems had become, due to under investments in the people who are the system’s backbone.

The organized global response that was required took a long time to get off the ground, which meant that nurses and other healthcare workers around the world found themselves in the midst of a crisis for which there seemed to be no immediate functional plan, no handy playbook, and no stockpile of vital life-saving equipment and supplies.

Before the storm — shortage of six million nurses

A joint venture between WHO, the International Council of Nurses (ICN) and Nursing Now, it provided the first-ever snapshot of the state of the global nursing workforce. And the picture was not a pretty one.

Findings included a global shortage of almost six million nurses, mainly in poorer countries.

A joint venture between WHO, the International Council of Nurses (ICN) and Nursing Now, it provided the first-ever snapshot of the state of the global nursing workforce. And the picture was not a pretty one.

Findings included a global shortage of almost six million nurses, mainly in poorer countries.

Among some 27.9 million nurses worldwide, there were also huge inequalities in the number of nurses per capita in different nations of the world, ranging from 8.7 nurses per 10,000 people in WHO’s Africa region to 83.4 in the Americas. Nine out of ten were women.

Among some 27.9 million nurses worldwide, there were also huge inequalities in the number of nurses per capita in different nations of the world, ranging from 8.7 nurses per 10,000 people in WHO’s Africa region to 83.4 in the Americas. Nine out of ten were women.

Inequalities income-driven

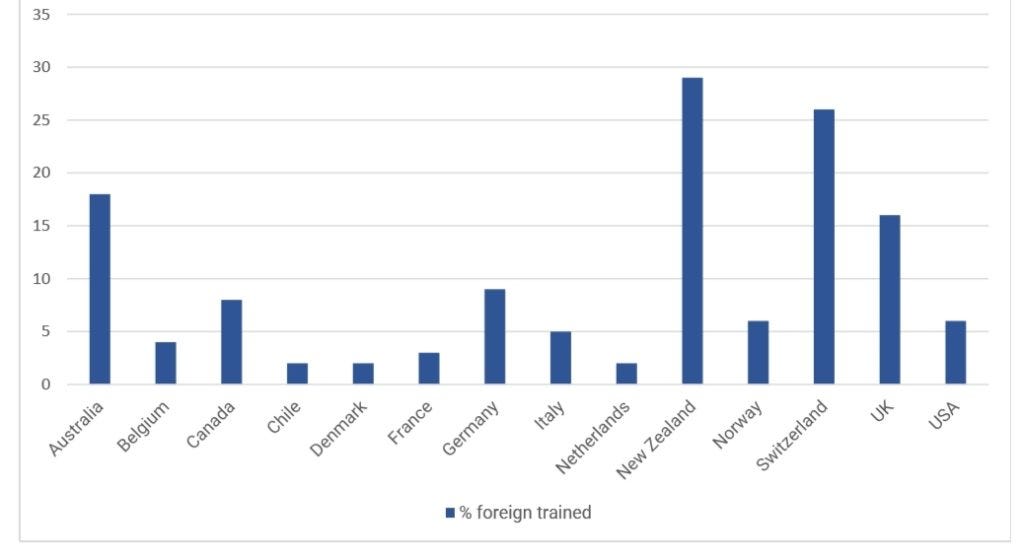

This imbalance was due to a general lack of investment and poor workforce planning, compounded by an over-reliance of wealthier nations on recruiting nurses from abroad, including lower-income countries which have fewer nurses in the first place.

The SOWN report called for massive investment in nurse education, jobs and leadership, so as to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the health-related aspects of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) .

The report also called for a programme of strategic investment in nurses to correct decades of complacency about workforce planning, which has always been too short-term, most often tied to government election cycles of four or five years. It concluded that such investment, continued over a much longer period, would also lead to more advancement in education, gender equality, the provision of decent work, and economic growth.

When the storm hit

But when the pandemic hit, those longer-term strategies and plans were once again put aside.

Issues that had to be faced were much more immediate.

Nurses were forced to cope with a highly infectious, and sometimes deadly virus, with little or no access to personal protective equipment (PPE), and little training or preparation. In some parts of the world, nurses cared for COVID-19 patients with little more than plastic gloves and aprons, and in some cases, even without access to running water.

While applauded by some communities, nurses also faced abuse, intimidation and violence from certain members of their communities, who were in denial about the virus or fearful about healthcare workers being carriers, according to the many messages received from our ICN National Nursing Association members around the world.

Dreadful toll

Unsurprisingly, the pandemic has taken a dreadful toll on the nursing workforce.

Unsurprisingly, the pandemic has taken a dreadful toll on the nursing workforce.

It has driven up demand for nurses, who are the critical “front line” health professionals, whilst at the same time cutting across nurse supply due to infection, increased absences — and thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, COVID-related deaths.

It has driven up demand for nurses, who are the critical “front line” health professionals, whilst at the same time cutting across nurse supply due to infection, increased absences — and thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, COVID-related deaths.

There are also more nurses who intend to, or are considering leaving the profession altogether.

Indeed, in the most recent survey (2021) of some 5000 nurses and nurse managers, 11% said they intended to leave their position soon, with proportions much higher among the most senior nurses.

… in the most recent survey (2021) of some 5000 nurses and nurse managers, 11% said they intended to leave their position soon, with proportions much higher among the most senior nurses.

ICN now believes that, with a further four million nurses planning to retire by 2030, and the as yet unclear and untold toll of what we are calling the COVID Effect on nursing numbers, the previously reported nursing shortage of 6 million could double to 12 million over coming years.

ICN now believes that, with a further four million nurses planning to retire by 2030, and the as yet unclear and untold toll of what we are calling the COVID Effect on nursing numbers, the previously reported nursing shortage of 6 million could double to 12 million over coming years.

In addition, nurses are experiencing increased mental health problems, as the intensity of their work has resulted in anxiety, stress and burnout.

All of that has been exacerbated by more frequent experiences with death, and in nurses having to take the place of family members and friends holding the hands of patients who would otherwise have died alone.

On top of this, moral injuries, which result from nurses being required to make or witness ethically challenging decisions about patient care delivery, also are on the rise.

Brighter side of the crisis

But while all this was happening, there was one small chink of brightness in all the gloom: the pandemic did lead to greater public and policymaker awareness of nurses essential function, and the value they provide to the societies they serve.

While many burnt-out nurses may be leaving the professions, younger groups are still entering the vocation — sometimes even more than before.

But while all this was happening, there was one small chink of brightness in all the gloom: the pandemic did lead to greater public and policymaker awareness of nurses essential function, and the value they provide to the societies they serve.

So two years on, as we move towards a different phase of pandemic response — we need to build on this positive residue of recognition in the importance of nurses and nursing — while focusing more policymaker and employers’ attention on the needs for adequate investments in nurses, decent pay, and support for nurses’ wellbeing and mental health needs.

But unless the global nursing workforce is brought up to full strength, even when the pandemic is finally over, grand plans about ‘healthcare for all’ will be nothing more than pipe dreams.

Preparing for the next pandemic — workforce investments

Investment in nursing capacity is also critical in preparing for future epidemic and pandemic risks.

Investment in nursing capacity is also critical in preparing for future epidemic and pandemic risks.

The report provides a blueprint for what is needed now. That is a decade-long, fully-funded global investment plan to bring the nursing workforce up to its required global size and strength — while correcting existing imbalances between countries in nursing staff, per capita.

This means better planning by governments about their nursing needs, based on concrete projections of requirements of health systems with a clear strategy to meet those needs, without relying on mass recruitment from low and middle-income countries to end the brain drain of nurses from LMICs.

ICN realizes this will be a tough call economically for governments, not least because of the financial effects of the pandemic, but it is necessary.

Just as the pandemic was unfolding, we witnessed a number of international efforts to raise the profile of nursing, including the WHO International Year of the Nurse and the Midwife in 2020 and last year’s Year of Health and Care Workers .

But frankly, they were not enough and their goals were diverted by the immediate crisis.

Nursing “offset credits” to countries that provide nurses

Along with better planning at national level, high-income countries must become more self-sufficient in training their own nurses to meet the increasing demands of their ageing populations, rather than actively recruiting nurses who were trained elsewhere.

The latter means that they are effectively exporting their nurse training costs to lower-income nations that can ill-afford that burden and the consequent nursing brain drain..

For example, according to the OECD, the proportion of foreign-trained nurses in 14 upper and high-income countries climbs as high as 16% in the United Kingdom and over 25% in New Zealand and Switzerland. At the same time, other developed countries such as Denmark, France and the Netherlands have much lower rates, comparatively, of imported nursing staff.

We think that low- and middle-income ‘donor’ countries should be compensated for losing their much-needed nurses.

An ‘offsetting programme’ along the lines of international carbon credits, whereby destination countries pay for a nursing school or for individual nurses to complete their training as a remittance for taking a poorer country’s nurses is one possible solution.

Nurses at the policymaking table

Finally, another critical element of a more forward-looking strategy is the greater inclusion of nurses — 90% of whom are women — in decision-making circles.

Finally, another critical element of a more forward-looking strategy is the greater inclusion of nurses — 90% of whom are women — in decision-making circles.

Those countries are flying blind: their policies will end up being short-sighted and incomplete.

Having nurses working in advanced roles, and services based on nurse-led models of care, are the keys to the brighter future we all deserve.

But nurses will only be able to fulfill their potential if all governments wake up to what they must do, and take action on the sustained measures necessary to bring about the massive growth in the nursing workforce that is needed right now.

Health and peace are inseparable

Fast forward to 24 February 2022. We can anticipate that the recent outbreak of war in Ukraine will only compound the challenges seen during the past two years of the pandemic with strapped healthcare services, and insufficient investment in nursing services.

Many governments will likely be looking to increase their defense spending, rather than enhance their health budgets.

Particularly in the vast WHO European Region, longer-term thinking will be even more difficult as health care systems struggle to respond to the immediate crisis — and the largest wave of refugees since World War II.

War and conflict are a threat to health and make health outcomes poorer. The international agreements we need to invest in and support our health systems and health workers will be more difficult to achieve.

We should never forget that health, peace and prosperity are inseparable.

And whenever I hear governments say they can’t afford to invest in their nurses? I say, they can’t afford not to invest.

And whenever I hear governments say they can’t afford to invest in their nurses? I say, they can’t afford not to invest

____________________________________________________

About the authors

Howard Catton, a registered nurse, is the Chief Executive Officer of the International Council of Nurses, a federation of more than 130 National Nursing Associations worldwide.

Image Credits: Tehran Heart Centre , Tehran Heart Centre , WHO, Korean Nurses Association, Shamir Medical Centre, Israel, International Federation of Nurse Anesthetists, Western Sydney University, ICN Report 2022.

Originally published at https://healthpolicy-watch.news on March 11, 2022.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION