TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL

the global coalition against corruption

January 2023

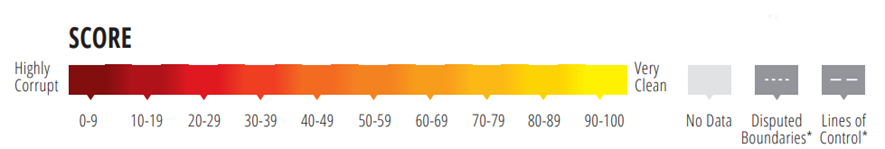

CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2022

Transparency International is a global movement with one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption.

With more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we are leading the fight against corruption to turn this vision into reality.

HOW DOES YOUR COUNTRY MEASURE UP?

The perceived levels of public sector corruption in 180 countries/territories around the world.

- The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map follow the UN practice to the best of our knowledge and as of January 2023.

- They do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of Transparency International concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The COVID-19 pandemic, the climate crisis and growing security threats across the globe are fuelling a new wave of uncertainty. In an already unstable world, countries failing to address their corruption problems worsen the effects. They also contribute to democratic decline and empower authoritarians.

This year’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) reveals that 124 countries have stagnant corruption levels, while the number of countries in decline is increasing. This has the most serious consequences, as global peace is deteriorating[1] and corruption is both a key cause and result of this.

Corruption and conflict feed each other and threaten durable peace. On one hand, conflict creates a breeding ground for corruption. Political instability, increased pressure on resources and weakened oversight bodies create opportunities for crimes, such as bribery and embezzlement. Unsurprisingly, most countries at the bottom of the CPI are currently experiencing armed conflict or have recently done so.

On the other hand, even in peaceful societies, corruption and impunity can spill over into violence by fuelling social grievances.[2] And siphoning off resources needed by security agencies leaves states unable to protect the public and uphold the rule of law. Consequently, countries with higher levels of corruption are more likely to also exhibit higher levels of organised crime and increased security threats.

Corruption is also a threat to global security, and countries with high CPI scores play a role in this. For decades, they have welcomed dirty money from abroad, allowing kleptocrats to increase their wealth, power and geopolitical ambitions. The catastrophic consequences of the advanced economies’ complicity in transnational corruption became painfully clear following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In this complex environment, fighting corruption, promoting transparency and strengthening institutions are critical to avoid further conflict and sustain peace.[3]

Leaders can fight corruption and promote peace all at once. Governments must open up space to include the public in decision-making — from activists and business owners to marginalised communities and young people. In democratic societies, the people can raise their voices to help root out corruption and demand a safer world for us all.

Daniel Eriksson

Chief Executive Officer, Transparency International

Recommendations

Dealing with the threats that corruption poses to peace and security must be a core business of political leaders. Prioritising transparency, oversight and the full, meaningful engagement of civil society, governments should:

- 1.REINFORCE CHECKS AND BALANCES, AND PROMOTE SEPARATION OF POWERS

- 2. SHARE INFORMATION AND UPHOLD THE RIGHT TO ACCESS IT

- 3. LIMIT PRIVATE INFLUENCE BY REGULATING LOBBYING AND PROMOTING OPEN ACCESS TO DECISION-MAKING

- 4. COMBAT TRANSNATIONAL FORMS OF CORRUPTION

- REINFORCE CHECKS AND BALANCES, AND PROMOTE SEPARATION OF POWERS

Anti-corruption agencies and oversight institutions must have sufficient resources and independence to perform their duties. Governments should strengthen institutional controls to manage risk of corruption in defence and security.[4]

2. SHARE INFORMATION AND UPHOLD THE RIGHT TO ACCESS IT

Ensure the public receives accessible, timely and meaningful information, including on public spending and resource distribution. There must be rigorous and clear guidelines for withholding sensitive information, including in the defence sector.

3. LIMIT PRIVATE INFLUENCE BY REGULATING LOBBYING AND PROMOTING OPEN ACCESS TO DECISION-MAKING

Policies and resources should be determined by fair and public processes. Measures such as establishing mandatory public registers of lobbyists, enabling public scrutiny of lobbying interactions and enforcing strong conflict of interest regulations are essential.

4. COMBAT TRANSNATIONAL FORMS OF CORRUPTION

Top-scoring countries need to clamp down on corporate secrecy, foreign bribery and complicit professional enablers, such as bankers and lawyers. They must also take advantage of new ways of working together to ensure that illicit assets can be effectively traced, investigated, confiscated and returned to the victims.

ENDNOTES

1 According to the Global Peace Index.

2 World Bank. 2011. World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security and Development. Washington DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/ curated/en/806531468161369474/ pdf/622550PUB0WDR0000public00BOX361476B.pdf

3 United Nations. 2021. “The UN common position to address global corruption: Towards UNGASS 2021”. New York: United Nations. https:// ungass2021.unodc.org/uploads/ ungass2021/documents/session1/ contributions/UN_Common_Position_ to_Address_Global_Corruption_Towards_UNGASS2021.pdf

4 Corruption risks within defence and security institutions in almost 90 countries are identified in Transparency International’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI). 5 “Significant” progress refers to an improvement backed by a majority of the CPI’s underlying data sources. Some countries have shown a score at least three points higher or lower than that which they received in 2012, but there is a substantial variation among the CPI’s underlying sources.

[1] According to the Global Peace Index.

[2] World Bank. 2011. World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security and Development. Washington DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/ curated/en/806531468161369474/ pdf/622550PUB0WDR0000public00BOX361476B.pdf

[3] United Nations. 2021. “The UN common position to address global corruption: Towards UNGASS 2021”. New York: United Nations. https:// ungass2021.unodc.org/uploads/ ungass2021/documents/session1/ contributions/UN_Common_Position_ to_Address_Global_Corruption_Towards_UNGASS2021.pdf

[4] Corruption risks within defence and security institutions in almost 90 countries are identified in Transparency International’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI). 5 “Significant” progress refers to an improvement backed by a majority of the CPI’s underlying data sources. Some countries have shown a score at least three points higher or lower than that which they received in 2012, but there is a substantial variation among the CPI’s underlying sources.

Originally published at https://images.transparencycdn.org/

Country to watch: Brazil

In the last four years, Brazil (38) faced an unprecedented dismantling of anti-corruption frameworks that had taken decades to build.

Despite repeated claims that he ran a corruption-free government, former-president Jair Bolsonaro, his cabinet ministers, allies and even family members were subject to corruption investigations.

His government created the largest institutionalised corruption scheme ever known in Brazil, known as the “secret budget.”

Through this scheme, billions of Reais were allocated to favour political allies, with serious impacts on health, education and infrastructure policies.

Bolsonaro’s government attacked civic space, with intimidation, defamation, fake news and direct strikes against civil society organisations, journalists and activists.

This period was also dire for the environment and the rights of indigenous people, women and the LGBTQ+ community.

This anti-democratic movement culminated on the assault of the national congress, presidency and supreme court buildings on 8 January 2023 …

… by Bolsonaro’s supporters, in an attempt to challenge the October election results in which now President Lula da Silva won. They vandalised the three buildings, while local police forces stood by. Following the attack, public authorities, some linked to former President Bolsonaro, were held responsible for negligence.

Even though violent anti-democratic attacks will be a challenge to president Lula da Silva´s administration, his government should find ways to address the current obstacles to anti-corruption.

President Lula’s ruling party, the PT, or Workers’ Party, has also been involved in major corruption scandals — including the one that led to the Operation Car Wash investigation that successfully brought a corruption case against him until the Supreme Court annulled his conviction.

However, it was also during Lula and his successor Dilma Rousseff’s administrations that Brazil made significant advances on anti-corruption.

Lula and his party have yet to offer a concrete anti-corruption plan for the future, nor laid out how they will re-establish the autonomy of key institutions, such as the Prosecutor General’s Office, Federal Police and environmental agencies.

By adopting transparent and ethical standards, and re-opening up government for social participation and scrutiny, the new government could have a positive impact in the region and beyond, especially in the Global South.