Centers of excellence have the potential to simultaneously decrease costs and increase value in surgical care.

NEJM Catalyst

David W. Dietz, MD, William V. Padula, PhD, MS, Hanke Zheng, MS, Peter J. Pronovost, MD, PhD

November 4, 2021

Summary

Health care is entering a new era in medicine and surgery in which the focus will elevate from the quality of care to its value.

As surgery accounts for nearly half of all Medicare spending, surgeons will have a critical role in this journey.

Defects in health care value are common, and the U.S. health care system spends $1.4 trillion annually — one-third of health care costs — on defects.

Quality of care in surgery refers to improved patient outcomes, increased patient satisfaction, greater yields in clinical effectiveness, and advancements in safety that deliver a timely, cost-efficient service.

Defects in these areas undermine value.

This article examines high-value care, low-value care, and no-value care around eight domains of defects in surgical care, using colorectal surgery to provide examples and national estimates of the costs of those defects.

Yet total cost is clearly underestimated as data to calculate opportunities is not available for some defects.

Defects in health care value are common, and the U.S. health care system spends $1.4 trillion annually — one-third of health care costs — on defects.

The objective of this article is to summarize a holistic approach to eliminating defects in surgical care as well as to offer a framework for centers of excellence for eliminating defects.

As surgery accounts for nearly half of all Medicare spending, surgeons will have a critical role in this journey.

Introduction

Improvements in surgical care have been breathtaking. Not long ago, aortic aneurysm repairs and liver transplantations were often fatal. Now, these operations are routinely performed, with most patients not only surviving, but achieving meaningful improvements in quality of life.

Such dramatic improvements in outcomes result from a tradition of introspection and innovation in surgery that dates back to the early 1900s and Codman’s seminal work to track outcomes, acknowledge errors, and seek improvements in care.1

We are now entering a new era in medicine and surgery in which the focus will be elevated from the quality of care to its value. “High-value health care” is achieved when excellent outcomes, including patient experience, are achieved at reasonable costs.2

As surgery accounts for nearly half of all Medicare spending, surgeons will have a critical role in this journey.

We believe that the next phase of surgical innovation will apply Codman’s principles of quality improvement across the entire continuum of surgical care to identify and eliminate defects in value.

Understanding Value in Surgery

Defects in health care value are common and can be defined as behaviors, based on known evidence, that needlessly reduce the quality of care and patient experience or add to the annual total costs of care.

In a previous report, one of us (P.J.P.) and colleagues estimated that the U.S. health care system spends $1.4 trillion annually — one-third of health care costs — on defects and found that focused efforts to reveal and reduce defects in a large health system improved quality and reduced Medicare costs by 9%.

In surgery, quality of care refers to improved patient outcomes, increased patient satisfaction, greater yields in clinical effectiveness, and advancements in safety that deliver a timely, cost-efficient service.

Defects in these factors of quality, such as surgical errors (e.g., wrong-side surgery), poor outcomes (e.g., sepsis), or ineffective care (e.g., tumor recurrence) undermine value.

Likewise, defects in value can relate to the time- or cost-dependent factors of surgery, such as an unexpectedly long hospitalization.

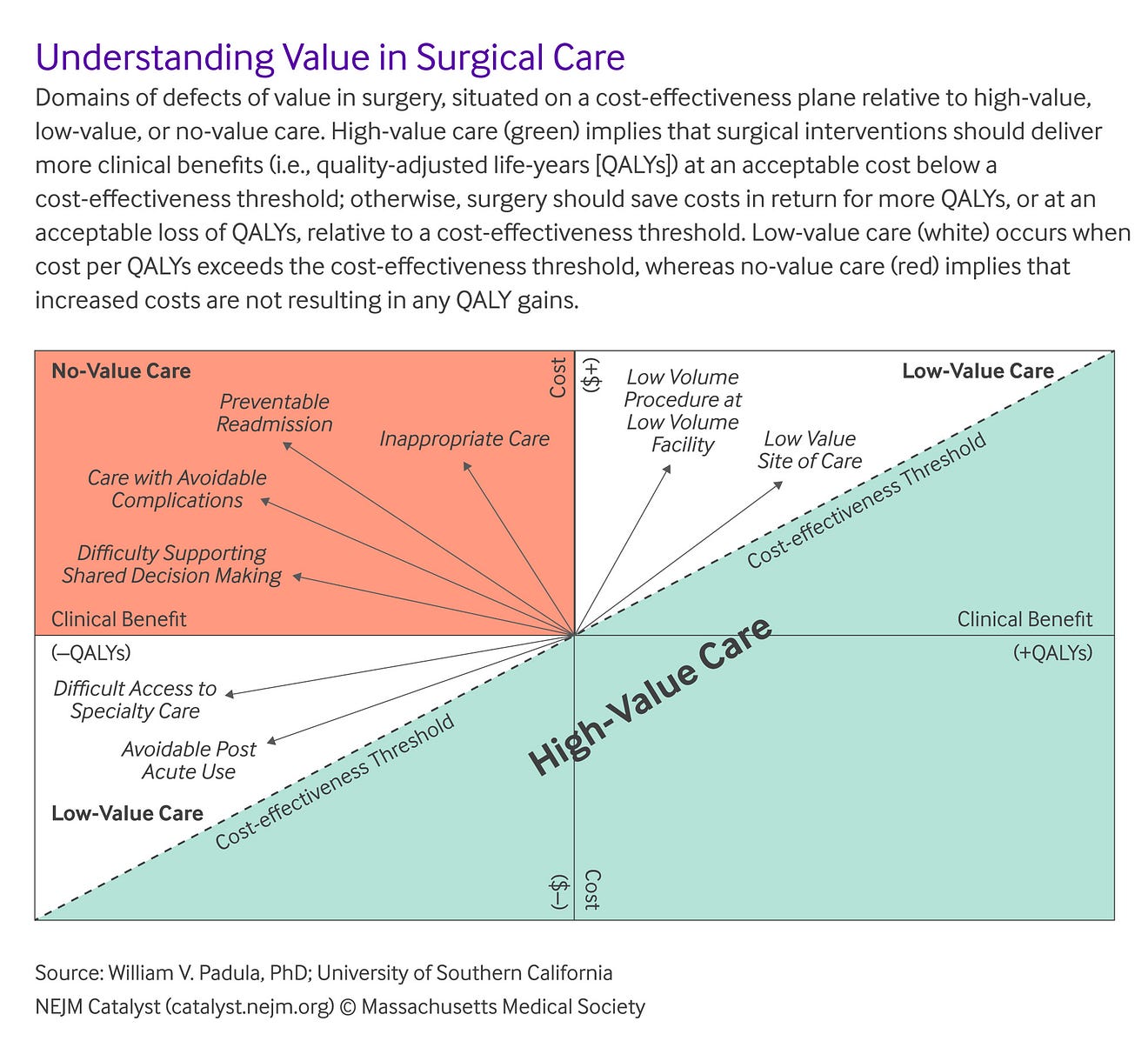

Each quality factor contributes to an understanding of value on a sliding scale. That is, high-value care and low-value care have some overlap in terms of quality and cost. High-value care can decrease cost while increasing clinical benefit, can cost slightly more for increased clinical benefit, or can decrease cost with acceptable reduction in clinical benefit ().

In contrast, low-value care can increase cost while yielding little or no clinical benefit, can cut cost but with an unacceptable reduction in clinical benefit, or can actually be harmful to the patient (“no-value care”).

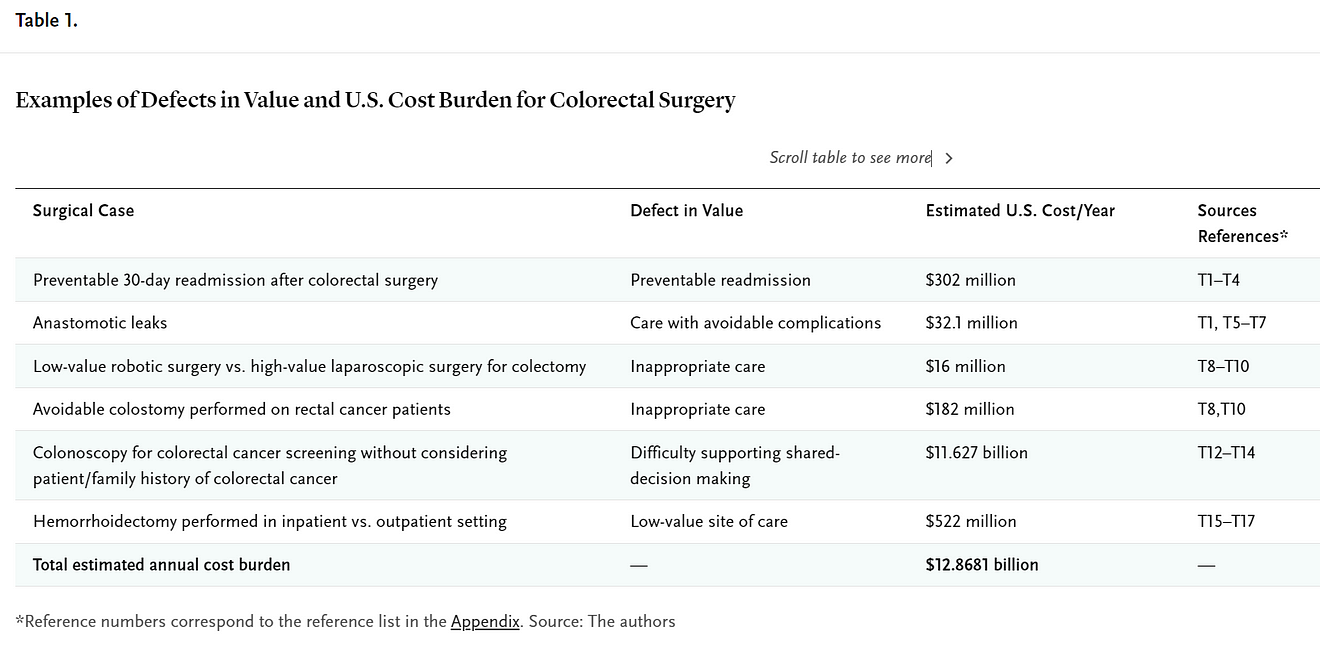

Here, we examine these definitions of value around surgical care in eight domains of defects and use colorectal surgery to provide examples along with national estimates of the costs of those defects ( Table 1).

Total cost is clearly underestimated as data to calculate the opportunities in some domains are not available. Our objective is to summarize a holistic approach to eliminating defects in surgical care and to offer a framework for centers of excellence for eliminating defects.

Difficulty in Accessing Care

For many patients, accessing specialty care is difficult. Patients with serious surgical problems are often forced to navigate the health care landscape alone and often are confused about where to seek care and what type of doctor to choose. In addition, patients seldom know about the quality of surgeons or hospitals or even basic metrics, such as annual case volumes performed by the surgeon and hospital.

Most patients make decisions based on word of mouth or physician referral.6 While this defect may or may not drive up costs, it results in low-value care by compromising patient experience and quality of life. For example, patients with rectal cancer who are treated by a nonspecialist surgeon are much more likely to end up with a permanent colostomy.7

We are now entering a new era in medicine and surgery in which the focus will be elevated from the quality of care to its value.

Difficulty Supporting Shared Decision-Making

Patients with complex surgical problems are often worried and do not understand their treatment options. Yet the current fee-for-service (FFS) system creates pressure on surgeons to see more patients, making it difficult for surgeons to spend adequate time answering questions and discussing treatment alternatives. In an effort to help, researchers have developed patient decision aids (PDAs) for diseases such as ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer, but these aids are rarely used in clinical practice.

These scenarios place health systems in penny-wise, pound-foolish situations in which providers feel forced to prioritize volume over patients’ values and goals.

This situation leads to less-satisfactory outcomes in which the same patients return for restorative care, thereby disincentivizing future patients from accessing the system due to lack of autonomy.

Upfront investments to engage patients in shared decision-making through PDAs and a shared decision-making model that follows three stages (team talk, option talk, decision talk) when consulting with a patient could avert many no-value care scenarios, save costs, increase revenues, and increase clinical benefits in the long run.

Inappropriate Care

For example, current evidence has dispelled many myths that once drove recommendations for elective surgery for diverticulitis.

Despite this evidence, rates of operative treatment continue to rise and recent population-based studies have shown increases of up to 38%.

Surgeons have also eagerly adopted new technology, which may add to treatment costs without meaningful improvements in outcomes, even if surgical treatment itself is indicated.

Examples of such no-value care can be found in much of the literature on robotic surgery.

For example, the randomized controlled trial by Jayne et al. showed that the robotic approach did not improve outcomes relative to rectal cancer surgery, and, while robotics have significantly increased costs, this technique is widely used and marketed.

… the robotic approach did not improve outcomes relative to rectal cancer surgery, and, while robotics have significantly increased costs, this technique is widely used and marketed.

Low-Value Site of Care

Many surgical procedures are performed at expensive inpatient facilities when they could be performed at an ambulatory center for 50% less.

Examples of such outpatient procedures include hemorrhoidectomy, endoscopy, and even minimally invasive bowel resections requiring only an observation stay.

Many surgical procedures are performed at expensive inpatient facilities when they could be performed at an ambulatory center for 50% less.

Care at Low-Volume Hospitals by Low-Volume Surgeons

The outcomes of many major surgical procedures are strongly correlated with the annual volume performed at the hospital and by the surgeon.

Yet many patients continue to be treated by low-volume hospitals and providers, even when a high-volume option is ❤0 miles away.

The outcomes of many major surgical procedures are strongly correlated with the annual volume performed at the hospital and by the surgeon

An analysis of the National Cancer Database shows that only 6% of U.S. hospitals are “high volume” for rectal cancer procedures and that only 25% of patients are treated in these centers (unpublished data).

When treated by low-volume providers, patients with rectal cancer are more likely to undergo abdominoperineal resection, to end up with a permanent colostomy, and to have worse survival.,

These scenarios place health systems in penny-wise, pound-foolish situations in which providers feel forced to prioritize volume over patients’ values and goals.

While the rectal cancer scenario describes the risks of seeking care at low-volume locations, this scenario borders more on low-value care than no-value care.

Thirty miles may seem like a reasonable distance to travel for major surgery, but social determinants may make it necessary for patients to seek local options. Individuals in dense urban areas, those with accessibility issues, underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, and the elderly may have limited capacity to seek care in one location compared with another.

Thus, a provider offering a service in a low-volume center still can deliver some clinical benefits to patients.

Even if rural areas are excluded, a significant amount of low-value surgery is still being performed in urban and suburban areas by low-volume surgeons and hospitals.

Care with Avoidable Complications

Colorectal surgery procedures are associated with some of the highest rates of postoperative complications. A recent study showed that 70% of patients have at least one complication, with an associated cost increase of nearly 40%.

The most serious complication of colorectal surgery — anastomotic leak — increases the cost of the index hospitalization by $8,000.

A reduction in the rate of anastomotic leak from 15% to 10% nationally would save $20.4 million annually.

If 75% of anastomotic leaks could be avoided after colorectal surgery, $32.1 million in health care costs could be saved annually in United States. The calculation details are presented in the Appendix.

Avoidable Post-Acute Care

D

ischarge to post-acute care is a common practice for patients undergoing any major surgery. Reasons for post-acute care include advanced age, poor functional status, and preventable postoperative complications.

In a study of >97,000 patients who had undergone elective colorectal surgery, 5% were discharged to a skilled nursing facility and 1% were discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility.21

Another study showed significant variability between hospitals in terms of post-acute care spending for patients managed with colectomy.22

Preventable Readmissions

Readmissions after surgery represent potentially low-quality care and increased costs to the health system.

Yet readmissions are also indicative of the patient’s health: either it is deteriorating or the patient gained no clinical benefit from the procedure. Such circumstances represent no-value care scenarios.

Approximately 14% of patients who have undergone colorectal surgery are readmitted after being discharged following the index hospitalization.

Commons reasons for readmission include surgical site infections, small bowel obstruction, and dehydration in patients undergoing ileostomy.

A single-institution study examined readmissions after colorectal surgery from 2013 to 2016 and showed that 40% were preventable.

The median cost per stay was $8,885 (based on 2002–2008 claims data); thus, $300 million in cost-savings could be achieved per year by preventing unnecessary readmissions after colorectal surgery.

Efforts to Eliminate Defects

Across the continuum, defects in surgical care result in substantive reductions in quality and patient experience and increases in costs.

While efforts have reduced individual defects in care, we are unaware of work to make all defects collectively visible and to design systems that might mitigate the entire problem.

Our health system has used design thinking to make visible and eliminate defects in surgical care.

The design concept is an explicitly defined center of excellence (COE) that identifies and eliminates each of these defects under one unified effort.

Given the abundance of opportunities presented, a “whack-a-mole” approach to address them individually seems inefficient and overwhelming. However, a holistic approach through the creation of COEs, if well designed and well executed, can address all of these defects.

Centers of excellence provide patients easy access and frictionless navigation to care services, have objective appropriateness criteria for services, and ensure that procedures are performed in the highest value setting by high-volume surgeons.

Moreover, COEs use standard protocols to reduce unwarranted variation and complications, provide personalized care when needed, have disciplined care-transition programs, and coordinate all postoperative care.

Opportunity Costs of Defects in Value

Each domain of defects in value represents an important philosophy in health economics that has consequences for all patients, referred to as opportunity costs. Opportunity costs are accrued from foregoing the next-best alternative.

When health systems spend above the cost-effectiveness threshold in a low- or no-value care situation, each dollar spent is a dollar lost that might provide clinical benefits to other patients.

When we spend below the threshold in the high-value care zone, we deliver clinically beneficial care to patients most of the time. Moreover, we free up resources that allow health systems to deliver the best available care to the patient in the operating room and the next patient in the waiting room.

Toward Eliminating Defects in Surgical Care

While prior reports have commented on individual defects in surgical care, we believe that the current article is the first to summarize the opportunity to reduce defects in surgical care.

While we cite specific examples in the field of colorectal surgery, there is an urgent need to address these defects across all surgical specialties.

If we are to finally improve the value of surgical care in the U.S., we need to ensure that surgeons are engaged in the process and that Codman’s time-honored principles for quality improvement are also applied to identify and eliminate all defects in value in surgical care.

While prior reports have commented on individual defects in surgical care, we believe that the current article is the first to summarize the opportunity to reduce defects in surgical care.

About the authors & affiliations

- David W. Dietz, MD

Chief, Division of Colorectal Surgery, and Vice President of System Surgery Quality, University Hospitals, Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, USA - William V. Padula, PhD, MS

Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmaceutical & Health Economics, School of Pharmacy, and Fellow, Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA - Hanke Zheng, MS

Graduate Research Assistant, Department of Pharmaceutical & Health Economics, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA - Peter J. Pronovost, MD, PhD

Chief Clinical Transformation Officer, University Hospitals; Professor, schools of Medicine, Nursing, and Management, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

References

See original publication

Originally published at https://catalyst.nejm.org on November 3, 2021.

TAGS: Quality Improvement; Patient Safety Improvement; Value Based Health Care (VBHC); Variation Reduction; Zero Defects Surgery; Zero Defects Health Care; Evidence Based Medicine; HTA;