Hopkins Medicine

By Linell Smith and Sue De Pasquale on

06/04/2021

Illustrations by Gordon Studer

When Nobel Prize-winning physician/scientist William Kaelin spoke recently at Johns Hopkins, he called the COVID-19 pandemic “an accelerant: accelerating many developments that would have taken decades to happen, if they happened at all.”

Indeed, the pace of change in medicine this past year has been breathtaking, happening at what Johns Hopkins’ calls “COVID speed.”

We surveyed experts in a variety of biomedical fields at Johns Hopkins to find out how breakthroughs and changes made in rapid response to the acute needs of COVID-19 may endure — to the benefit of patients, trainees and biomedical science.

Findings:

- Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials

- More Telehealth in Psychiatry

- Going Public with Bioethics

- Addressing Isolation in Aging Patients

- Broadening Access for Trainees

- Breaking Down Professional Hierarchies

- Improving Vaccine Design

- Saying So-Long to Data Siloes

1. Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials

Namandje Bumpus: “Let’s think about diversifying scientists, too.”

Namandje Bumpus, the first African American woman to lead a department at the school of medicine, studies genetic differences that influence how people metabolize drugs used to treat HIV. Her research aims to correct a long-standing limitation of scientific inquiry.

“Most studies are done on European American males in their 20s. But there are so many people missing in that picture,” says Bumpus, director of the Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences. “Genetic variation can impact the way drugs are processed and can make certain drugs work differently for some people. To understand this, we need to make sure that clinical trials are diverse and accessible.”

Because the pandemic highlighted the health care disparities that exist for Black, Latinx and Indigenous people, the clinical trials created for the COVID-19 vaccine have been among the most diverse to date in terms of including volunteers from different races and older age groups.

“There was a good effort at recruiting and also at placing [clinical trial] sites that were accessible to Black and Latinx people,” says Bumpus. As a result, “the Pfizer and Moderna COVID vaccine trials were both about 10 percent for African Americans — not quite our representation of 12 percent in the U.S. — but a really good showing,” she says.

Looking to the future, Bumpus believes the success of this effort will have a lasting impact, prompting scientists to include more diverse patient populations for clinical trials of all types.

“It is now definitely on people’s minds, which is positive progress,” she says. “But let’s think about diversifying scientists, too. If we have scientists in the room who are thinking about things such as certain genetics that are more prevalent for various ethnicities, it’s more likely that we will develop a drug that will work for all.”

2. More Telehealth in Psychiatry

Jimmy Potash: “The nature of psychiatry lends itself to telehealth to a far greater degree than most other specialties.”

When members of the American Psychopathological Association (APPA) met recently to explore the mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, they discussed increases in anxiety, depression and substance use disorder. But they also addressed the rise of telemedicine and its ability to connect people more easily to psychiatric care.

“That might well prove to be a favorable development for the long haul,” says Johns Hopkins psychiatrist Jimmy Potash, who serves as APPA president. “The nature of psychiatry lends itself to telehealth to a far greater degree than most other specialties because we don’t have to physically lay hands on people most of the time.”

In March 2020, the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, which Potash directs, began converting most of its outpatient program to telehealth. Not only has the change extended care to more patients by saving them travel and time, but it has also increased practice efficiency.

“One of our largest outpatient clinics used to have a cancellation and no-show rate of about 30 percent that is now down to 18 percent,” Potash says.

The technology can also yield greater insights into patients. “In psychiatry, it’s always important to understand the illness in the context of who the person is and what their life is like. When you see a person at home, you learn things by seeing their physical environment or their interaction with people who come in and out of the room.”

Moreover, Potash says that patients who are “intensely private or intensely shy” sometimes struggle with in-person clinical sessions. “They really find it easier to open up with the distance that the virtual setting provides.”

3. Going Public with Bioethics

Jeffrey Kahn: “We need to package our bioethics work so that it is useful beyond just our academic peers.”

Ever since he staffed a “bioethics booth” at the Minnesota State Fair in the mid-1990s, Jeffrey Kahn has been eager to broaden the discussion of ethics beyond the ivory tower. The pandemic, he says, has served as a catalyst to make that happen.

Last October, Kahn — the Andreas C. Dracopoulos Director of the Johns Hopkins Berman Bioethics Institute — announced that the institute would be rolling out a new “public bioethics” program, the first of its kind and one that he hopes will become a model for other academic centers to follow.

“This past year has shown us a real need and value for this kind of effort, since virtually every aspect of our nation’s response to COVID involves an issue of bioethics,” says Kahn. As just a few examples he points to the allocation of scarce medical resources like ventilators, the balance between personal freedom and public safety in wearing masks, and decisions surrounding the closing and reopening of schools and businesses.

Kahn says the initiative at Johns Hopkins, which will launch with the institute’s new Bloomberg-Dracopoulos iDeas Lab later this year, will tap into the latest media strategies (including using digital, audio and video tools) to share the research and analysis of Johns Hopkins bioethics faculty with journalists, policymakers and the public at large. The overarching goal: to inform public discussion and debate and ultimately impact policy decisions.

Kahn first realized the value of bringing bioethics into the public conversation when he was a young researcher at the University of Minnesota, where the university’s academic units were expected to do public outreach each year at the state fair.

“I was very reluctant. After all, it was a challenge to engage fair-goers about bioethics when we were competing with butter sculpture and champion livestock,” he says. “But I was won over by the interest we had from the public and we got more creative over the years with our presentations. People loved it, and I thought, ‘Why aren’t we doing this more and outside of the fair?’”

Soon after, he began writing a biweekly column, “Ethics Matters,” for CNN.com. “When I write an article for an academic journal, I may be lucky to have 1,000 people read it, ever,” Kahn says.

“With the CNN column, I got tens of thousands of page views per week, and it reinforced for me that if you really want to affect public policy and inform the general public, we need to package our bioethics work so that it is useful beyond just our academic peers. I hope that the iDeas Lab and our Public Bioethics Program will lead the way.”

4. Addressing Isolation in Aging Patients

Ariel Green: “Family members could be vital allies in reorienting and engaging older adults with cognitive impairment during a hospitalization.”

The images were like a punch to the gut: elderly people in nursing homes and hospitals, cut off from family and friends for weeks and months because of COVID-19’s cruel toll.

Johns Hopkins geriatrician Ariel Green says the pandemic brought public attention, at last, to a heartbreaking problem that geriatricians have long recognized: the isolation older patients experience while living in skilled nursing facilities and being treated in hospitals. “So often we fail to meet their psychosocial needs,” she says. “What COVID has laid bare is that in general, for older adults with functional and cognitive impairments, we think it’s OK for them to languish in bed without any stimulation for days.”

Noting that hospitals are busy and complex places, Green says, “we become so focused on the medical side of things that we lose track of our patients’ psychosocial needs and the emotional distress they are experiencing, so we turn to medication to treat their pain or help them stay calm, when in fact it would be more effective to have them talk to someone, listen to music or engage in activities that focus on their strengths, promote dignity and facilitate coping.”

Pointing to the effectiveness of Child Life programs in pediatric medicine, which aim to reduce stress and anxiety in hospitalized children through education, preparation and play, Green says, “we have nothing similar to that in adult medicine.” She’s hoping the new public awareness brought by the pandemic might lead to the expansion of programs like this and the establishment of a specialty modeled after Child Life.

In the wake of the COVID-19 response, Green would also like to see “a greater recognition of the importance of family caregivers for older adults with cognitive impairment.” In nursing homes, assisted living facilities and hospitals, Green notes, “family members are more than just visitors: They are an essential part of the health care team and COVID-19 has illuminated how terrible it is when older adults are cut off from their caregivers.”

Too often, she says, family caregivers feel excluded in the clinical environment, when the reality is that if they are properly encouraged and enlisted, they could provide valuable help with eating, repositioning to prevent pain or pressure sores, communication and even physical therapy.

“Family members could be vital allies in reorienting and engaging older adults with cognitive impairment during a hospitalization,” Green says. “This could go a long way toward preventing delirium — the acute confusion that often occurs during hospitalization and leads to a cascade of adverse health outcomes for older adults.”

And in the community setting, Green is hoping that COVID-19 might lead to better public policy and funding to support family members in caring for their elders at home.

She says, “It’s currently much easier for me to get insurance to cover a test or procedure that costs thousands of dollars, and has little chance of benefitting an older adult, than it is to get my patients and their families the support services they need to continue living at home. Except in limited circumstances, families generally have to pay out of pocket to get help with activities of daily living, like dressing and bathing, and that’s exorbitantly expensive.

“As geriatricians,” says Green, “our hope is that the suffering and isolation we’ve seen during the pandemic might inspire a change in direction for the care of older adults.”

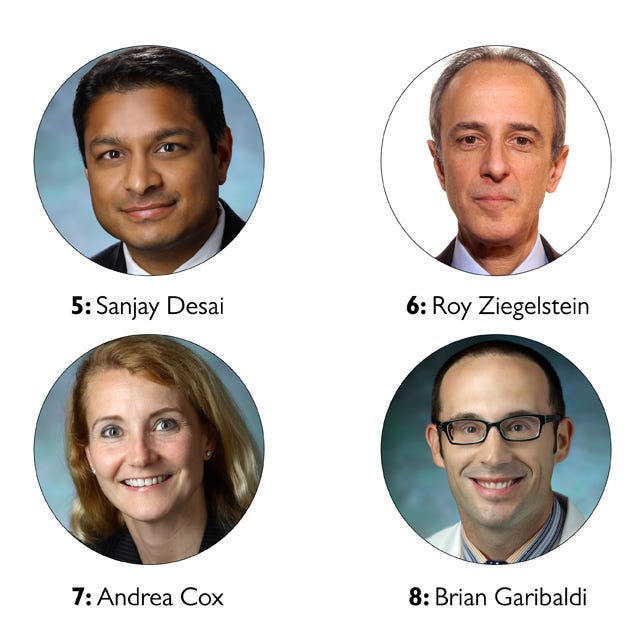

5. Broadening Access for Trainees

Sanjay Desai: “Our applicants have saved tens of thousands of dollars by not having to visit all of the places they are applying to. That is really important for issues of equity.”

Almost overnight, it seems, COVID-19 brought an end to in-person lectures and group meetings. Sanjay Desai, director of the Osler Medical Training Program, says that converting in-person educational forums into virtual settings has created “an accessibility that we’ve never had before. We easily almost doubled Medical Grand Rounds viewership, and the numbers of people who see our educational content has gone up substantially.”

Offered to medical students, house staff, fellows and other graduate students, Medical Grand Rounds at Johns Hopkins are held every week. Before the pandemic, up to 100 people would gather in Hurd Hall amphitheater to learn about the analysis and treatment of difficult clinical problems in real-life patients — often from patients who tell their own stories.

Since moving to an online format in April 2020, participation in Grand Rounds has averaged well over 200, and for some lectures the number of participants is in the thousands.

Equally important, according to Desai, is how the technology has increased audience engagement.

“Chat [a Zoom participation option] enables people to ask questions they wouldn’t ask in an in-person setting, and to ask them while the speaker is speaking. That means that while the second speaker is speaking, the first can be responding. There are also opportunities for small group discussions. When we return to in-person sessions, we will have to keep parts of the virtual format because it allows for more interaction.”

Desai has also realized that the technology benefits medical students who are applying for residencies. All of the interviews for the Osler residency program this year were conducted virtually.

“Our applicants have saved tens of thousands of dollars by not having to visit all of the places they are applying to. That is really important for issues of equity,” he says. “At the same time, we were able to create engaging virtual interactions with our applicants. Given the substantial benefits to applicants we will continue a largely virtual recruitment process even post-pandemic.”

6. Breaking Down Professional Hierarchies

Roy Ziegelstein: “The pandemic has really prompted people to think deeply about what they do, about what their limits are, and about other people’s contributions to patient care.”

As medical centers across the country set up COVID-19 isolation units and implemented new safety protocols, interprofessional collaboration got a big boost, says Roy Ziegelstein, vice dean for education.

“The pandemic helped to reinforce the importance of teamwork and to break down the system of hierarchy that can have detrimental effects in academic medicine,” he says. “I think that having residents and fellows work on an even playing field with faculty — and also work even more closely with nurses, social workers and case managers — leads to a better approach at improving care to patients and families.”

Over the course of the grueling months that health care professionals have worked side by side to meet the extraordinary needs of patients with COVID-19, “the relationships, openness and communication have all changed in a really good way,” says Ziegelstein, “and I’m really hopeful that will stick.”

He says the past year has underscored principles of interprofessional collaborative practice that nursing and medical students acquire early on in their education at Johns Hopkins — and he hopes it will influence how they shape their own clinical practices.

“There’s a lot that medical students learn in the pre-clerkship experience that is not reinforced later when they are fully immersed in the patient care environment,” says Ziegelstein. “Doctors, nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists and social workers often don’t work together as closely as might be ideal. They sometimes don’t appreciate the unique skills each brings to the care of the patient.

“Now, everyone appreciates one another more. The pandemic has really prompted people to think deeply about what they do, about what their limits are, and about other people’s contributions to patient care.”

7. Improving Vaccine Design

Andrea Cox: “We’ve had some of the most brilliant minds in the world think about how to improve vaccine design and to find ways to rapidly advance vaccine production.”

For years, Andrea Cox has been investigating ways to create an effective vaccine against hepatitis C virus (HCV), a blood-borne virus infecting an estimated 71 million people around the world, which is a leading cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer.

The urgency of developing an effective program to prevent the spread of COVID-19 has tested a new type of vaccine that uses the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) platform — and that offers hope for her own research.

While many vaccines put a weakened or inactivated germ into the body to trigger an immune response, mRNA vaccines work by teaching the body’s own cells how to make a protein — or even just a piece of a protein — to accomplish that task. The resulting immune response protects against infection by the real virus.

“These mRNA vaccines have been so effective against SARS-CoV-2 that this platform will be considered for other pathogens, including HCV,” says Cox, who directs the medical scientist training program.

Hundreds of clinical trials are now in various stages of testing mRNA to prevent and treat infections and chronic diseases, according to Cox. Efforts are underway to develop “universal” flu vaccines, as well as vaccines for other infectious agents, such as Ebola and Zika viruses.

In the race to find an answer to COVID-19, “we’ve had some of the most brilliant minds in the world think about how to improve vaccine design and to find ways to rapidly advance vaccine production,” she says. “I think this will ultimately benefit vaccine development against many serious infectious diseases.”

8. Saying So-Long to Data Siloes

Brian Garibaldi: “As we broaden our focus beyond COVID-19, there are many, many projects that will benefit from advances in data modeling and collaboration across institutions.”

As the medical director of the Johns Hopkins Biocontainment Unit, pulmonologist Brian Garibaldi was among the first to care for patients coming into the hospital with severe COVID-19. Almost immediately, he began meeting with other front-line clinicians to share observations that could help shape care protocols and clinical trials — at Johns Hopkins and beyond.

“We were only about two or three weeks into the pandemic, when Antony Rosen, vice dean for research for the school of medicine, asked me a simple question: ‘What percentage of our patients have had a lab value of this particular amount?’ And I replied, ‘Gee, Antony, I can tell you anecdotally, but I can’t recall all of them.’”

“‘We don’t have a data repository?’ Antony asked. ‘We have to create one right now!’”

And so, they did. In the course of a weekend, the scientists conceived and submitted a plan for what has become the JH-CROWN registry, a collection of data and information about patients having suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection, that utilizes the Johns Hopkins Precision Medicine Analytics Platform. While the main source is Johns Hopkins’ electronic medical record system, Epic, the registry also includes data from other sources, such as biospecimen repositories and physiologic device monitoring systems.

Currently there are more than 40 scientific teams across Johns Hopkins that have gotten IRB approval to use data from JH-CROWN to advance their research. And that exemplifies a significant shift that Garibaldi believes will continue beyond COVID-19.

“With data registries, there’s long been this sense that ‘I’m the principal investigator and you can’t work with the data unless you work with me,’” says Garibaldi. “But with COVID-19, there’s no one person or group who can possibly tackle all of the different questions that can be answered with this data. There’s been an urgency to give access to as many investigators as possible. As a result, we are bringing teams together who might not have known they are working on similar questions. This is an approach to team science that can lead to very rapid discovery — and I’m hopeful it will carry forward for other projects and other data sets.”

From a data sharing perspective, Garibaldi has also observed moves to develop large “mega-cohorts” of patients and to partner across institutions to share data. For example, data from the JH-CROWN registry is also being shared with the National COVID Cohort Collaborative, which is collecting and harmonizing data from different institutions across the country into a “data enclave” for use by investigators all over the nation.

“We’ve had 6,000 inpatients with COVID-19 at Johns Hopkins, but across the country there have been millions of hospitalized patients,” notes Garibaldi. “We have so much to learn, in understanding epidemiology and prediction modeling, for example, from these huge cohorts.”

Making the most of disparate data sets requires translating data from individual institutions into common models that allow data to be easily shared — work that has been ongoing at Johns Hopkins for the last several years by a variety of expert teams.

“As we broaden our focus beyond COVID-19, there are many, many projects that will benefit from advances in data modeling and collaboration across institutions and there is a lot of excitement in the health sciences world,” says Garibaldi. “This work has really been accelerated by the pandemic and the need to share data and generate discovery quickly.”

Originally published at