the health strategist

institute for

strategic health transformation

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Chief Research & Strategy Officer (CRSO),

Chief Editor and Senior Advisor

August 28, 2023

What is the message?

The newer pharmacologic agents for the management of patients with T2D and/or obesity appear to alter the natural history of these two common interrelated disorders and may represent a therapeutic breakthrough.

However, a number of questions now need to be addressed:

- Once a desired body weight has been achieved, how can it be maintained? Should the dose of the agent(s) be reduced?

- If prolonged, or even lifetime pharmacotherapy is necessary, will these drugs continue to be tolerated?

- Are they safe and effective in children and adolescents with obesity?

- Will drug-induced weight loss be of benefit in obese patients with HFpEF, with or without T2D?

- What are the long-term effects of weight control on non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a common accompaniment of chronic obesity?

- Can health systems and/or individual patients afford these agents at current prices?

The clinical management of T2D and obesity has, until now, been conducted by primary care physicians, by general internists, and in some instances by endocrinologists or diabetologists.

- Cardiologists have dealt largely with complications of T2D, usually resulting from ASCVD.

- However, they have also played important roles in the control of hypertension and dyslipidaemias.

If the results of SELECT are confirmed (see above), cardiologists will be obliged to do the same for the prevention and management of T2D and/or obesity, …

… an effort that could have a profound beneficial effect on the development of ASCVD, still the most common global cause of death in adults.

This will require additional training and perhaps even the creation of a new subspecialty — diabetocardiology?

Infographic

DEEP DIVE

Diabetocardiology: a new subspecialty?

European Heart Journal

Eugene Braunwald

23 August 2023

Newer anti-diabetic agents

Early in this century, amid a marked global increase in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D), a new class of anti-diabetic drugs — the sodium glucose cotransport inhibitors (SGLT2i), often referred to as the gliflozins, was developed. By blocking the reabsorption of glucose in the proximal renal tubule, they cause glucosuria. The resulting reduction in the circulating glucose led to their approval for the treatment of T2D. A serendipitous finding was that gliflozins are also beneficial in patients with heart failure (HF). What came as a surprise to many, including this author, was that this benefit was substantial, was equal in magnitude in patients with and without T2D, and was observed in HF patients across the entire spectrum of ejection fraction. These observations led to a paradigm shift in the management of HF. Furthermore, the gliflozins also slow the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD), including diabetic kidney disease (DKD).1

In 1987, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), an enteric hormone (incretin) that stimulates postprandial insulin secretion, was discovered.2 Analogues of GLP-1, the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), became another class of anti-diabetic agents. They also reduce glucagon release and, importantly, delay gastric emptying and reduce appetite, leading to weight loss, thereby amplifying their hypoglycaemic action. These agents reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), slow the deterioration of kidney function, and diminish hepatic steatosis and systemic inflammation.3,4

Obesity

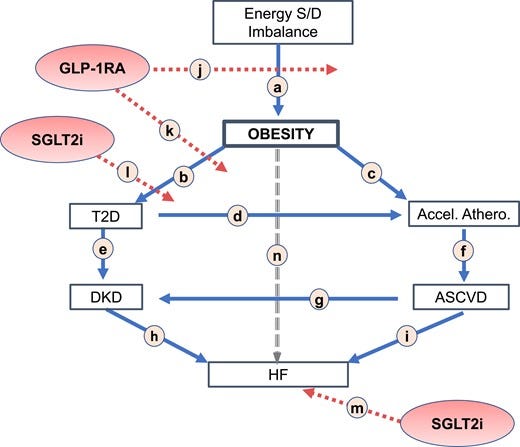

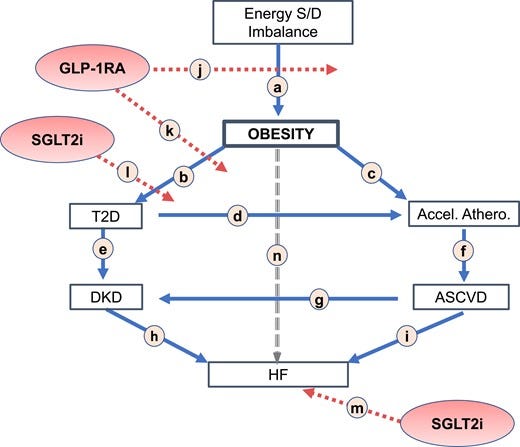

Obesity, generally defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2, is a chronic, global health problem that currently affects more than 650 million adults worldwide, 44.1% of the US population (pre-COVID), and is among the most common disorders contributing to the global burden of disease (several of the studies of obese persons discussed herein include overweight subjects with BMI 27.5–30 kg/m2 with at least one weight-related complication); it is increasing rapidly in prevalence with the aging of the population and the increasing availability of high-caloric ‘fast’ foods. Obesity is both an important risk factor for and risk marker of cardiovascular disease that is often associated with hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and a systemic inflammatory state.5 The increase in visceral adipose tissue is responsible for greater insulin resistance, frequently resulting in T2D; indeed, ∼90% of patients with T2D are either obese or markedly overweight. Obesity and T2D, both independently and in combination, accelerate atherogenesis (Figure 1), leading to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), left ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation, HF, obstructive sleep apnoea, reduced quality of life, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality. The chronic hyperglycaemia of T2D also causes microvascular dysfunction, which can manifest as DKD6 and as retinopathy.

Figure 1

Development, consequences, and control of obesity, diabetes, and heart failure. (a) Obesity is caused largely by chronic imbalance between energy supply and demand; (b) obesity is a risk factor for diabetes (type 2 diabetes) and © atherosclerosis; (d) type 2 diabetes accelerates atherosclerosis; (e) type 2 diabetes causes diabetic kidney disease; (f) atherosclerosis causes atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; (g) atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease contributes to the development of diabetic kidney disease; (h) diabetic kidney disease contributes to the development of heart failure; (i) atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease causes heart failure; (j) glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist reduces development of obesity; (k) glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist reduces development of type 2 diabetes; (l) sodium glucose cotransport inhibitor reduces severity of type 2 diabetes; (m) sodium glucose cotransport inhibitor prevents and reduces heart failure and diabetic kidney disease; (n) a possible direct line between obesity and heart failure. S, supply; D, demand; T2D, type 2 diabetes; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; GLP-1RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SGLT2i, sodium glucose cotransport inhibitor.

Treatment of obesity

Marked weight loss in obese persons, irrespective of how it is achieved, reduces arterial pressure, heart rate, and resting oxygen consumption, as well as pulmonary artery and wedge pressures.7 It also increases insulin sensitivity and reduces glycaemia, causing complete or partial remission of T2D and in the progression of pre-T2D to T2D.

Six first-generation monoagonistic GLP-1RAs have been tested in Phase 3 trials, which confirmed the above-mentioned actions.3 They have been followed by the development of tirzepatide, a synthetic peptide which combines a GLP-1RA with a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP).8 This first-in-class ‘twincretin’ is a dual receptor agonist in which the two components of a single molecule act in a complementary manner to increase insulin sensitivity and reduce weight. The SURPASS programme compared tirzepatide to placebo and to a variety of other hypoglycaemic agents in patients with T2D, demonstrating its superior anti-glycaemic potency and reduction of body weight, blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and circulating triglycerides compared to the first-generation monoagonist GLP-1RAs. In SURMOUNT-1, a placebo-controlled trial in obese persons without T2D, the subcutaneous weekly administration of 15 mg tirzepatide led to an average reduction of body weight of 20.9% and an average waist circumference reduction of 18.5 cm.9

New findings

The annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) in June 2023 featured a number of important trials that reflect further progress in this rapidly moving field.

- SURMOUNT 2, building on SURMOUNT 1, compared tirzepatide to placebo in obese persons with T2D; the same dose (15 mg weekly) was associated with a 14.7% reduction of weight.10

- Thus, the weight reduction with tirzepatide was less in patients with than without T2D, as observed with other weight-reducing drugs.

Three new studies of semaglutide, a first-generation monoagonistic GLP-1RA with potent weight loss effects, were reported.

- In a phase 2 trial in patients with T2D, the co-administration of weekly injections of semaglutide and cagrilintide, an analogue of amylin which reduces weight through a complementary mechanism, resulted in greater weight reduction than either agent alone.11

- In PIONEER PLUS, a Phase 3b trial in T2D patients, higher daily doses of oral semaglutide (25 and 50 mg) were found to be superior to the previously approved lower doses in reducing both HbA1c and body weight.12

- In OASIS 1, a Phase 3 trial, the 50 mg daily oral dose resulted in a mean body weight reduction of 15.1% in obese or overweight adults.13

- Orforglipron, a non-peptide partial GLP-1 RA agonist, given orally to adults with obesity with T2D resulted in a mean weight reduction of 14.7%.14

- Retatrutide, a triple–hormone-receptor agonist [GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors (GCG)], reduced body weight by a mean of 24.2% in a Phase 2 trial in obese non-diabetic subjects15; this represents the greatest weight loss of any pharmacologic regimen reported to date, approaching the results achieved by bariatric surgery.

Comments

The GLP-1RAs alone or associated with other incretin-like drugs are, in general, well tolerated. The most common adverse events involve the gastrointestinal system, causing nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and constipation. These are usually mild or moderate, dose dependent, and rarely require drug discontinuation. Commencing treatment with a very low dose and increasing it gradually can reduce their incidence and severity. Importantly, they do not by themselves cause hypoglycaemia.

At the time of this writing (August 2023), five first-generation monoagonist GLP-1RAs and tirzepatide have been approved for glycaemic control in Europe and the USA. Two of the former, liraglutide and semaglutide, have also been approved for weight loss and cardioprotection. On 8 August 2023, the sponsor announced the principal results of SELECT (NCT0357497), a cardiovascular outcome trial (CVOT), conducted in 17 604 obese or overweight adults without T2D. When compared to placebo, semaglutide (2.4 mg/week subcutaneously) showed a 20% significant reduction in MACE.16 Two other CVOTs of tirzepatide, SURMOUNT (NCT0556512) and SURPASS (NCT04255433), are ongoing. In addition, several trials in obese patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are ongoing, including STEP-HFpEF (NCT04788511) and STEP-HFpEFMD (NCT04916470) with semaglutide and SUMMIT HFpEF (NCT04847557) with tirzepatide.

A consensus report of the ADA and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) emphasized that reduction of cardiovascular and renal complications of T2D with SGLT2i and/or GLP-1RA, and weight and glycaemic control are key components of the management of T2D.17

Since SGLT2i are effective in the prevention and treatment of HF, they should be selected for T2D patients with left ventricular dysfunction or overt HF (Figure 1).

The GLP-1RAs are more potent hypoglycaemic and weight-reducing agents than SGLT2i and are preferred for T2D patients who are obese and/or require vigorous glycaemic control.

Combined therapy (SGLT2i and GLP-1RA) may be employed in patients at very high cardiovascular risk.

Conclusions

The newer pharmacologic agents for the management of patients with T2D and/or obesity appear to alter the natural history of these two common interrelated disorders and may represent a therapeutic breakthrough. However, a number of questions now need to be addressed: Once a desired body weight has been achieved, how can it be maintained? Should the dose of the agent(s) be reduced? If prolonged, or even lifetime pharmacotherapy is necessary, will these drugs continue to be tolerated? Are they safe and effective in children and adolescents with obesity? Will drug-induced weight loss be of benefit in obese patients with HFpEF, with or without T2D? What are the long-term effects of weight control on non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a common accompaniment of chronic obesity? Can health systems and/or individual patients afford these agents at current prices?

The clinical management of T2D and obesity has, until now, been conducted by primary care physicians, by general internists, and in some instances by endocrinologists or diabetologists. Cardiologists have dealt largely with complications of T2D, usually resulting from ASCVD. However, they have also played important roles in the control of hypertension and dyslipidaemias. If the results of SELECT are confirmed (see above), cardiologists will be obliged to do the same for the prevention and management of T2D and/or obesity, an effort that could have a profound beneficial effect on the development of ASCVD, still the most common global cause of death in adults. This will require additional training and perhaps even the creation of a new subspecialty — diabetocardiology?

References

See the original publication (this is an excerpt version)