Applying the ‘7 Lenses of Transformation’ approach in interviews with 7 national digital leaders, former UK IT chief Kevin Cunnington has investigated the biggest barriers to successful digital reforms.

Here, we set out 7 key findings from our research — mapping out the essential foundations of true digital transformation

Global Government Forum — Digital.

November, 2021

therantimes

Executive Summary

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Digital Health and AI . institute

March 30, 2022

Introduction, by Kevin Cunnington

Around the world, civil service digital leaders have a similar set of ambitions — aiming to strengthen the evidence that informs policymaking, the tools provided to civil servants, and the efficiency, accessibility and targeting of public services. And with countries at very different stages of development, there are obvious opportunities for central digital chiefs to learn from one another about how best to pursue those common goals.

Hence this research project. Global Government Forum concentrates on helping senior civil service leaders to explore and address the issues they face in common; and as a former director general of the UK’s Government Digital Service, I wanted to help my colleagues around the globe to make faster progress on digital transformation.

Our solution was the ‘7 Lenses of Transformation’ system, developed in 2018 within the UK government (see Our Research, below).

In the event, we found a number of areas in which digital leaders’ messages were closely aligned.

These clustered around three major topics:

- creating and implementing a vision;

- investment and project funding; and

- leadership and capabilities.

This research will now inform Global Government Forum’s editorial coverage and events programme — shaping not only the publisher’s work with digital professionals, but also its Summits for heads of civil services and national finance leaders: many of the changes required to drive digital transformation lie in the hands of organisational leaders or the heads of other professions, so this conversation must run well beyond the bounds of the digital and data function.

GGF also intends to develop events aimed at countries operating in a specific set of circumstances, where the challenges are most aligned and the lessons most transferrable.

Meanwhile, we hope these findings will be useful to senior digital leaders around the world.

Kevin Cunnington

Director General of the Government Digital Service, UK, 2016–19

November 2021

Our research

See the original publication (for the complete version. This is only an excerpt of it)

These digital leaders worked within seven very diverse governments: while all the countries are middle- or high-income, their constitutions, political contexts and national characters were very different.

Within a small sample size, we aimed to test the 7 Lenses methodology with a wide range of countries — exploring the extent to which common lessons can be drawn, while identifying fields in which further research would be best continued within smaller groups sharing specific constraints or challenges.

Chapter 1

Creating and implementing a vision

Finding 1: Visions often depict a future picture of great digital services — but unless governments detail the levers, resources and reforms required to realise their goals, progress is typically slow and shallow

Finding 2: To realise their vision of seamless services wrapping around the user, countries must develop two essential capabilities:

- strong digital ID systems, and

- high-quality, cross-government data management

Chapter 2

Investment and project funding

Finding 3: Nations need to renew capital investment spending in digital, and to commit the money required to transform legacy systems

Finding 4: Government-wide project funding, approval, governance and procurement processes are often poorly suited to the requirements of digital technologies, undermining delivery

Chapter 3

Leadership and capabilities

Finding 5: Good progress has been made on capabilities at the junior and middle levels, though there’s a need to further organise and develop digital workforces

Finding 6: Constrained pay for top digital roles leaves many civil services unable to recruit or retain the quality of talent required to lead transformation

Finding 7: Departmental leaders and ministers often lack the understanding and commitment to drive digital transformation

Conclusions

In all our interviewees’ countries, digital leaders have made progress over recent years — particularly on digitising citizen-facing services, building skilled workforces, and demonstrating the power of digital and data technologies.

But behind these outward similarities, there is a substantive gap between those nations well advanced in identifying and putting in place the foundations of effective digital transformation, and those much further behind on this journey.

Within the former group, digital leaders are equipped to realise ever more of the potential value of their governments’ data assets, while rapidly rebuilding public services around a smart, accessible, citizen-centred model.

But leaders within the latter set of nations face far more obstacles and costs in delivering individual digital projects, and lack the cross-government leadership, policies and platforms required to embed new digital services within a coherent, unified public services offer.

As well as highlighting a number of these foundational conditions, our research revealed some of the reasons why their prevalence is so patchy.

In some cases, control over the changes required to put these essential building blocks in place lies well outside the digital space; and here Global Government Forum — whose global audience spans the civil service functions and specialisms — can best serve public servants by supporting discussions and partnerships across departmental and professional boundaries.

One common perception among CIOs, for example, is that digital programmes demand the wholehearted engagement and support of departmental leaders — who, most felt, tend not to actively drive reforms forward.

Another strong message concerned the cross-government systems governing processes such as procurement, spending approval and project management, which often fail to recognise the specific needs of digital technologies.

In other cases, countries’ constitutional, cultural, political and technological legacies are so diverse that, while digital leaders’ goals remain similar, their starting points — and thus the tasks required to realise those goals — have little in common.

Here, CIOs will benefit most from engaging with those whose circumstances broadly mirror their own.

The most obvious example concerns the creation of digital ID systems. Nations that operate a national ID system have a relatively straightforward route to developing a digital version, building it around the unique citizen identifiers underpinning their existing systems.

These countries’ CIOs have a huge amount to learn from one another — addressing topics around delivery, uptake and international compatibility, for example — but much less to offer those starting from scratch in creating a cross-government citizen ID system.

Those lacking a national ID system face much more fundamental questions around design and implementation.

Around the world, they’ve approached the challenge in many different ways, building up huge experience in what works — and here mutual support can be enormously helpful in cutting costs, shortening timescales and averting mistakes.

Finally, our research identified a set of important issues where all of our interviewees face comparable challenges as they work to put these digital fundamentals in place.

One example is the need to ensure that digital ‘visions’ go beyond painting a picture of the future, explaining exactly how governments will get from here to there — and thus mapping out a realistic path to delivery.

Another concerns skills, where most countries could benefit from greater professionalisation and the development of organised digital and data ‘functions’ — creating strong career pathways, improving recruitment and retention, and fostering a more flexible workforce.

Meanwhile, we hope that the insights and messages in this report prove useful to senior civil servants working in the digital sphere and beyond it.

The foundations of digital transformation look broadly similar around the world; and while the task of building them may vary from country to country, those underlying commonalities make digital one of the most fruitful fields for stronger international learning, exchange and collaboration.

For digital leaders — both at the centre of government, and in departments — strengthening civil servants’ use of technologies can seem a lonely task, set about by tensions with other agendas, professions, teams and departments.

But you are not alone: in every country, your peers are trying to reach a similar destination.

There’s a huge amount to gain by comparing notes along the way: as the Turkish proverb says, ‘No road is long with good company.

Case Studies

On the full version of the report, you´ll find CASE STUDIES about

- Estonia

- Israel

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

Introduction, by Kevin Cunnington

Around the world, civil service digital leaders have a similar set of ambitions — aiming to strengthen the evidence that informs policymaking, the tools provided to civil servants, and the efficiency, accessibility and targeting of public services. And with countries at very different stages of development, there are obvious opportunities for central digital chiefs to learn from one another about how best to pursue those common goals.

Hence this research project. Global Government Forum concentrates on helping senior civil service leaders to explore and address the issues they face in common; and as a former director general of the UK’s Government Digital Service, I wanted to help my colleagues around the globe to make faster progress on digital transformation.

Reviewing the research landscape in this field, it became clear that most previous projects have focused on creating global benchmarking systems: league tables, ranking governments on their digital progress and prowess. But while these can be useful in identifying high performers, they’re often of very limited value to national digital leaders.

For one thing, their assessment criteria too often remain opaque; and even where they’re published, methodologies take little account of each country’s unique constitution, culture, politics, and technology legacy. Yet these environmental factors shape the landscape within which digital leaders must operate, deciding whether a particular tool or technique has any practical value. The ‘copy the best’ approach may suit consultancies eager to sell a single product globally, but effective solutions must be built around a country’s specific characteristics and situation.

What’s more, knowing which countries are doing well and which badly does not help us to explain why that is — and for digital leaders, the really useful information is not who’s making progress, but how those in similar circumstances are doing so. To answer that question, we need to investigate the nature of the obstacles and constraints that hamper digital chiefs — exploring both their frustrations, and the ingenious ways that many have found to overcome these barriers.

So we needed a research methodology that could explore each country’s specific circumstances — recognising that issues around legacy, constitution and culture, for example, make this a highly uneven playing field — and identify both the most widespread challenges facing digital leaders, and the solutions they’ve adopted. This process would generate information on which strategies and systems have proved most effective within a range of different circumstances: not just what works, but what works where. On the global platform, there is no such thing as ‘best practice’: people need to know what has worked for others in similar situations.

Our solution was the ‘7 Lenses of Transformation’ system, developed in 2018 within the UK government (see Our Research, below). In the event, we found a number of areas in which digital leaders’ messages were closely aligned. These clustered around three major topics: creating and implementing a vision; investment and project funding; and leadership and capabilities. Despite the diversity of our interviewees’ situations, their experiences, successes and frustrations had much in common; and while their solutions will have to match their circumstances, we were able to frame seven shared challenges. We set these out below, along with comments on some of the factors that are enabling or hampering progress in different countries.

This research will now inform Global Government Forum’s editorial coverage and events programme — shaping not only the publisher’s work with digital professionals, but also its Summits for heads of civil services and national finance leaders: many of the changes required to drive digital transformation lie in the hands of organisational leaders or the heads of other professions, so this conversation must run well beyond the bounds of the digital and data function. GGF also intends to develop events aimed at countries operating in a specific set of circumstances, where the challenges are most aligned and the lessons most transferrable.

Meanwhile, we hope these findings will be useful to senior digital leaders around the world.

Kevin Cunnington

Director General of the Government Digital Service, UK, 2016–19

November 2021

↑ Contents

Our research

To produce this research, Global Government Forum (GGF) — the publishing house for civil servants around the world — teamed up with Kevin Cunnington. Kevin is a senior UK digital leader: he spent his early career in programming and IT consultancy, later becoming the global head of online for Vodafone Group and director general of the Business Transformation Group at the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). He was director general of the UK’s Government Digital Service (GDS) from August 2016 to July 2019, and digital envoy for the UK and director general of the International Government Service until 2021.

To produce the report Kevin worked with Matt Ross, a journalist specialising in public sector leadership and management issues. Matt was features editor of weekly news magazine Regeneration & Renewal 2002–08, and editor of the UK title Civil Service World 2008–14. He has worked with GGF since 2015, and is currently a contributing editor focusing on special projects.

The research comprised interviews with seven national digital leaders, all working at the centre of government to drive transformation across the civil service:

- Shahar Bracha, Acting Chief Executive Officer, Government ICT Authority, Israel

- Geoff Huggins, Director of Digital, Scottish Government

- Fariz Jafarov, Director of the E-GOV Development Center, Azerbaijan

- Paul James, Government Chief Digital Officer, New Zealand

- Siim Sikkut, Government Chief Information Officer and Deputy Secretary General of IT and Telecoms, Estonia

- Aaron Snow, Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Digital Service, Canada (now a Faculty Fellow at the Beeck Center for Social Impact and Innovation, Georgetown University, USA)

- Tan Eng Pheng, Assistant Chief Executive — Services, GovTech Singapore

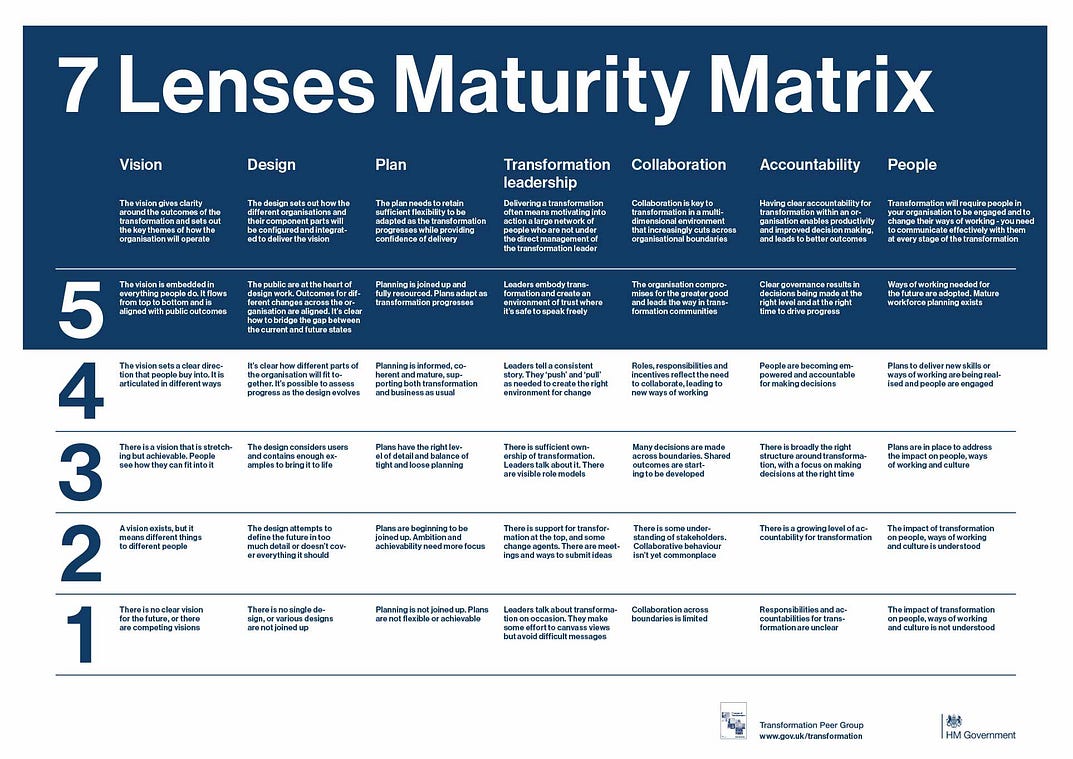

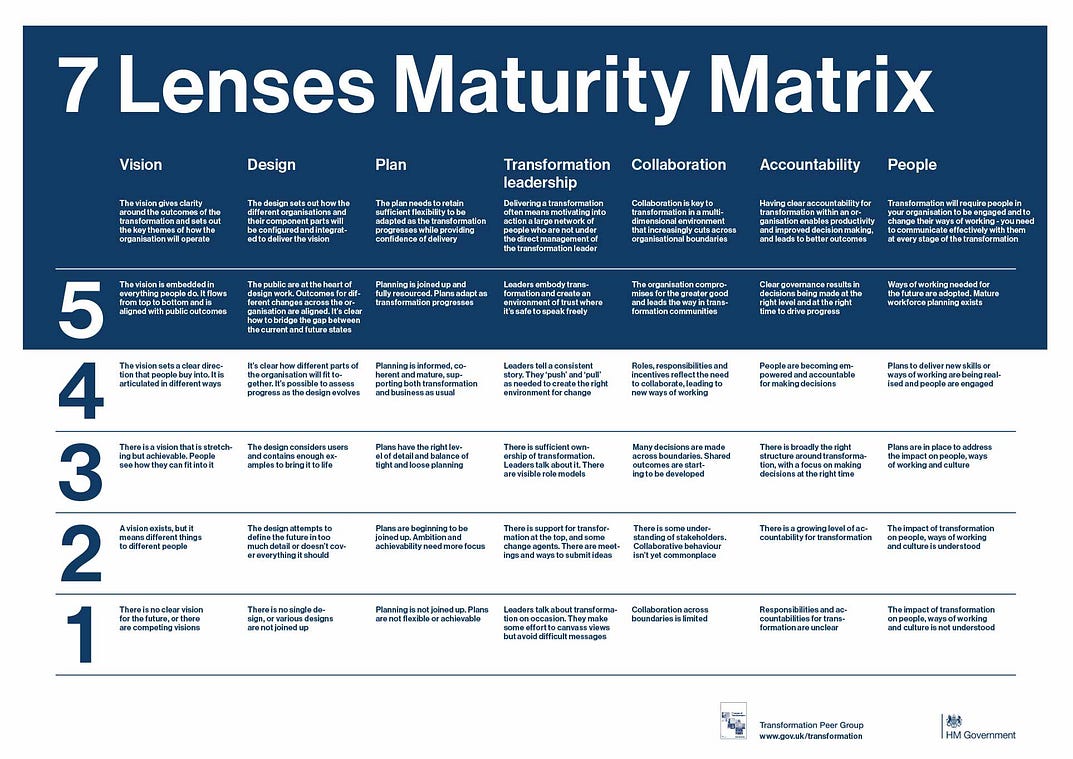

To structure the interviews, we used the ‘7 Lenses of Transformation’ method — developed by the UK government in 2018 to test some of its biggest, most complex reform projects against the principles underpinning digital best practice (see image below).

The methodology was applied within the UK government by Kevin and Tony Meggs, chief executive of the Infrastructure and Projects Authority. As co-chairs of the Transformation Peer Group, they worked with senior programme management professionals across government to assess their programmes — going through the Lenses’ seven-strong checklist of essential elements. During that work, they found two common errors: many programme managers had begun work before they had all these essential components in place; and they’d failed to provide a clear vision of what needed to be achieved. For more information on the 7 Lenses approach, see the UK government’s explanation.

Later, Kevin and Tony used the methodology to look more holistically at individual UK departments’ transformation plans. And now, Kevin is working with GGF to apply it to national governments’ central digital strategies and operations. During this project, we’ve identified areas in which the 7 Lenses could usefully be refined and developed: if the results of this pilot project prove useful to civil service digital leaders, we will further improve the methodology and plan out a second stage of research.

During the interviews, we asked the digital leaders to rate their country’s progress and performance on the 7 Lenses, and explored with them the reasoning behind their scores. We have not sought to evidence or test interviewees’ self-assessments, deploying the 7 Lenses more as a qualitative than a quantitative research method: the system’s main strength here lay in its ability to catalyse discussions around a consistent framework. Interviews were conducted on Chatham House Rules, so the quotes in this report are not attributed to individuals.

These digital leaders worked within seven very diverse governments: while all the countries are middle- or high-income, their constitutions, political contexts and national characters were very different. Within a small sample size, we aimed to test the 7 Lenses methodology with a wide range of countries — exploring the extent to which common lessons can be drawn, while identifying fields in which further research would be best continued within smaller groups sharing specific constraints or challenges.

The report is presented in three chapters, each comprising an introduction and two or three key messages. We also include three boxed texts illustrating some of the solutions to the challenges set out by our interviewees.

Chapter 1

Creating and implementing a vision

Most countries have a vision in place, so average scores on the ‘vision’ lens came out close to four out of five. But a vision only depicts your planned destination; it can’t show how you’re going to get there. And it’s when that journey is described in detail that all the complexities, compromises and challenges of implementation are laid bare — which is, of course, why governments sometimes fail to muster the courage and consensus required to bite this particular bullet.

So producing a vision is very much the easy part of this strategic planning process — not least because, given the characteristics and opportunities of today’s digital technologies, many countries’ visions portray similar pictures of the future. Digital identity systems guarding interdepartmental service delivery platforms; migration and transformation of services from legacy systems into the Cloud; cross-government data management and the use of unique identifiers; automation, user-focused design and platform services — the core elements of strong digital public services are pretty much universal.

However, the existence of a vision alone is not sufficient to guarantee substantive progress towards it. That requires a delivery plan — and most countries were weaker on the ‘design’ and ‘plan’ lenses that explore this aspect of strategic policymaking. Individual nations’ route maps show far more variation than their visions; and this diversity is important, reflecting their different starting points, constitutional and political arrangements, and public perceptions. The key requirement is to spell out — and win the support and funding required for — the major infrastructure, process and culture changes required to deliver their vision; without that, it’s easy to get stuck making piecemeal reforms to individual services rather than embarking on true digital transformation.

Where the vision document isn’t supported by a detailed implementation plan promoting substantive, wholesale reforms, then paper documents give way to online forms; manual processes are automated; new websites are launched — and the users receive a faster, more reliable service. But underlying business processes remain fundamentally unaltered, dependent still on ageing and much-patched legacy systems. While countries have managed to transform some major systems — particularly in tax assessment and collection — too often digitalisation simply wraps a shiny new skin around a creaking IT infrastructure, realising only a relatively small proportion of the potential benefits of today’s technologies.

Finding 1: Visions often depict a future picture of great digital services — but unless governments detail the levers, resources and reforms required to realise their goals, progress is typically slow and shallow

Applying the 7 Lenses methodology to assess departmental transformations and programmes inside the UK government, we often found that vision and strategy documents were vague and generic — setting out the goal of ‘digitising government’ without prioritising tasks, allocating funding, or detailing implications such as changed roles or responsibilities.

Yet where these more difficult and controversial issues have not been addressed as the vision is developed, they tend to cause problems during implementation. On understanding the expense and disruption involved in full transformation, for example, some leaders and staff resist reforms. A reluctance to be specific in high-level plans about the powers required to drive progress can result either in the centre having inadequate levers, or departmental resistance further down the line. A lack of prioritisation can result in confusion and incoherence as leaders and organisations pursue different aspects of the vision. And a failure to include hard targets, reporting mechanisms and compliance procedures — with senior organisational leaders held accountable against delivery — can rob the agenda of momentum as organisations pay lip service while directing their energy at more immediate priorities.

“One of the most important things that has to happen with leadership is that they have to say out loud that change is going to be uncomfortable,” said one interviewee, noting that many strategy documents “contain nothing objectionable, and also nothing actionable.” Spelling out the reforms required to deliver the vision may create friction as plans are developed, but if those arguments aren’t held — and won — at this early stage, then digital leaders can find themselves lacking the powers, resources and buy-in required to transform government.

To be fair, some countries have made good progress on digital without a detailed national strategy. One interviewee from a digital front-runner explained that “there was no master plan that outlines each and every step; only the directions of travel” — noting the “readiness to experiment” within their civil service, where leaders are often willing to “see what works, and build it out from there like a classic start-up.” But this approach requires an entrepreneurial, flexible, collaborative civil service culture — very much a rarity — and was only observed in small countries, which can benefit from strong personal relationships and relatively straightforward stakeholder landscapes.

Typically, the most advanced digital governments have built their progress on multi-year, long-term strategies — created in collaboration with delivery departments, whose leaders’ progress against defined, measurable outcomes is monitored by central bodies on a regular basis. “We have a very sensible, thorough process for taking the vision on an annualised basis, and converting it into something that people have to execute in a very specific way,” commented one interviewee, while another noted that “the agencies’ progress and results are monitored on a yearly basis, with a detailed scorecard covering their process improvements.”

Finding 2: To realise their vision of seamless services wrapping around the user, countries must develop two essential capabilities: strong digital ID systems, and high-quality, cross-government data management

Almost all governments started their digital journey working on single services — often replacing paper forms with web-based data collection. Whilst this approach has many benefits, it fails to address the fragmented and disjointed experience that citizens experience when dealing with stand-alone services.

Digital services hold out the prospect of utterly transforming citizens’ interactions with government, massively reducing delivery costs while providing far more accessible, targeted and user-focused support for citizens. To catalyse these reforms, many governments have focused on ‘life events’ such as births and bereavements: the aim is that, rather than the citizen having to manage separate interactions with all the relevant departments, government provides a unified, semi-automated service that distributes data to wherever it’s required. This requires two capabilities: departments must be able to share and match data on individuals, addressing any discrepancies between their datasets; and citizens need a single, secure, online access point.

These same capabilities offer many further opportunities. Given an agreed way to match up the data they hold around citizens or organisations, for example, departments can develop a much fuller picture of service users’ situations, needs and behaviour — ‘personalising’ and automating services, improving coordination, and strengthening preventive work. In democratic countries with strong data protection laws, such work requires individuals’ approval; and this is most easily granted within a secure online space where citizens can manage their interactions with a range of public bodies, granting or rejecting requests to share data. Such spaces, of course, also much improve the accessibility and convenience of services.

So countries need a single citizen digital identity system, built around either a ‘unique identifier’ — such as the reference numbers lying at the core of many national ID systems — or a ‘golden record’: a ‘single source of truth’ held by a designated civil service body. And citizens must be able to log into a digital ID verification platform, securing access to a wide range of public services. Until they develop these capabilities, governments are condemned to manage an ever-growing number of mismatching data sets, often while citizens accumulate separate sets of log-in details for every individual service — creating a future of fast-rising confusion, cost and complexity. Even creating a single log-in system doesn’t necessarily permit departments to share data on identified individuals with confidence; for that, public bodies must embed this common system of citizen identifiers into their own datasets.

So digital ID verification and a system of cross-government citizen identifiers lie at the heart of effective national digital strategies — and even where countries have already cracked these challenges, central direction and cross-government planning is required to promote integrated, cross-departmental services built around ‘life events’. “True user needs are in bundles,” commented an interviewee from one of the more advanced nations; but development of the services to recognise those holistic requirements “doesn’t come bottom-up naturally from departments; we had to engineer that collaboration in, top-down.”

These days, the ultimate aims of digitalisation are widely recognised and shared. But countries will always struggle to realise these goals unless they can find shared ways of both talking about individuals, and providing secure access to online services. Over the last 20 years, many nations have made good progress on digitalisation; they will, however, require these two capabilities to move forward on true digital transformation.

Case study: data management and ID verification in Estonia

“Estonia has been building up a digital country for the last 20 years, and 99% of transactional public services are available online — the only exceptions being marriage and divorce. All other services are personalised, with public bodies barred from requesting information from citizens if another part of government already holds that data. The government is currently working to take personalisation and service experience to the next level, combining interactions around life events and business events into integrated and proactive bundles — aiming for one minimal interaction per event.

This has been made possible by platform services, and by the legal and governance framework underlying digital government. Estonia has used a national digital identity system since 2002, with ID cards — and more recently mobile ID — forming the mandatory authentication (login) and authorisation (digital signing) systems for any public service.

The base for digital ID is a single identifier set-up (a personal or company code), which enables personalisation through combining of data for seamless interactions — assuming that the law permits or consent is given. The integration of data itself is enabled by data governance guidelines ensuring that data is good quality, properly catalogued, and shared via the X-Road data-sharing platform.”

Siim Sikkut, Government Chief Information Officer, Estonia

Chapter 2

Investment and project funding

The 7 Lenses do not specifically mention investment and funding, but we covered these subjects under ‘plan’, ‘transformation leadership’ and ‘accountability’. Resourcing is of course crucial not only to digital transformation, but also to the maintenance of existing IT-based and online services — and several interviewees made important points on the topic, shaping the messages below.

Finding 3: Nations need to renew capital investment spending in digital, and to commit the money required to transform legacy systems

Some years ago, several nations invested large sums in digital skills, strategies and services — building infrastructure such as digital ID systems, establishing central teams and dramatically improving online services. But interviewees noted that capital investment has since declined in some countries, leaving many public services dependent on ageing, outdated legacy systems. Until these systems are replaced or renewed, the opportunities for true digital transformation remain limited — while the costs and complexity of ongoing maintenance, licensing and cybersecurity continue to rise.

A few years back “government made a big investment in getting online, and it reaped the benefits,” commented one interviewee. “Things have degraded over time; everything becomes more ‘legacy’ with every passing day.” Digital transformation isn’t a one-off event, but an ongoing process: a decades-long programme, demanding firm funding commitments running as far as governments budgetary horizons permit. Fresh and continuing investments are required to rebuild departmental systems, strengthen data management, and create better connections between departments; and where this money is not available, nations’ public sector IT infrastructures and digital services are condemned to a period of relative decline.

Finding 4: Government-wide project funding, approval, governance and procurement processes are often poorly suited to the requirements of digital technologies, undermining delivery

In recent years, civil service technology professionals have embraced a digital world — leaving traditional IT working practices behind, and adopting techniques such as open source software and user-focused design. In perhaps the biggest single change, they’ve steered away from commissioning monolithic, predefined IT systems from a handful of big firms, instead using in-house staff and small businesses to develop new services by iteration and experiment. And to realise the potential of digital technologies, many countries are building cross-departmental services that better meet user needs while cutting transaction costs.

However, few civil service-wide systems have fully adjusted to these changed working practices or the unique requirements of digital technologies. Under iterative, ‘Agile’ project management, for example, systems are designed through experimentation during the production process — but business planning and budget approval systems typically require detailed plans of the final system before money is released, pushing project managers back towards inappropriate ‘Waterfall’ project management techniques.

“Agile is butting up against the architecture of the finance arrangements in our country — so the business case rules have been predicated on Waterfall methodologies and large-scale capital investments around people or property,” commented one interviewee. “An Agile methodology is a poor fit with how you get money.” Another noted that “there isn’t a lot of incentive to start small and learn as you go. There’s a lot of incentive to get the big blast of funding first — then the people who want that money swoop in.” The rush to spend can push business owners into dependence on consultancies, and incentivise them to quickly purchase of off-the-shelf systems rather than undertake slower but more thorough business process transformations.

Many countries have made good progress on improving procurement — introducing buying frameworks and streamlining pre-approval systems, for example. The best have built strong relationships with ecosystems of small and specialist providers: one runs an annual conference engaging with hundreds of developers. Even among the better performers, though, rigid and time-consuming procurement rules remain a frustration: “You need a tender: six months to write 200 pages of documents,” said one interviewee. “For the time being, government procurement is a major barrier. It needs to adopt to modern times.”

To realise the potential of digital technologies, national leaders must ensure that these cross-government systems — which lie outside digital leaders’ control, in fields such as finance, commercial, project management and legal — evolve to meet today’s goals, opportunities and risks.

The power of people: Israelis’ entrepreneurial culture

Civil service systems and processes rarely favour the experimentation and risk-taking essential to innovation, but these behaviours are more pronounced in some cultures — making it easier for officials to carry forward reforms. Israel’s Shahar Bracha, Acting CEO of the Government ICT Authority, highlighted three of his nations’ characteristics that, he believes, have helped the country make strong progress on digital transformation:

“First, we’re not afraid to try and fail.

“Second, we are not polite: we don’t wait for something to happen; we see something that’s missing, call it out, and act upon it. Sometimes it’s considered a bit rude, but we jump into the conversation and say what we think.

“And third, we are accustomed to improvising. It’s a part of our culture and that’s a big part of what makes us the startup nation.

“It’s not about the technology: it’s always about the culture — about the people, and how they work.”

Chapter 3

Leadership and capabilities

The crucial topics of workforce, skills and leadership fall most obviously under the ‘transformation leadership’ and ‘people’ Lenses. But equally relevant is ‘accountability’, measuring whether and how scrutiny and performance management systems push senior digital and organisational leaders to deliver on the government’s goals — and here, there was more variation between countries’ performance than in any other field.

On ‘people’, Lens scores ranged between two and four, averaging just under three: nobody’s cracked it, but all our interviewees were broadly content with the digital capabilities available across government at the more junior levels.

At senior levels, meanwhile, the past generation of IT leaders have largely been replaced by digital specialists. And ministers are often enthusiastic about the opportunities presented by digital technologies, if uninformed on how to realise that potential; in some cases, national political leaders are actively driving progress.

However, pay constraints and competition from private sector employers often make it hard either to recruit talented digital leaders into senior roles, or to retain digital professionals as they move into the management cadre. Equally seriously, it’s almost universally the case that top departmental leaders — permanent secretaries, chief executives and their peers — don’t understand digital; are very reluctant to prioritise digital goals over day to day operational challenges; and hate taking the risks involved in genuine transformation projects.

So on ‘transformation leadership’, scores ranged from two to 3.5, averaging a little over 2.5 — and marking this out as an area of weakness across the board. On ‘accountability’, though, scores ran all the way from one to five. These scores were noticeably higher in countries with metrics-based, centrally-monitored delivery targets, where leaders put themselves on four or five; where these are absent, our interviewees were far more pessimistic about their chances of overseeing far-reaching digital transformations.

Finding 5: Good progress has been made on capabilities at the junior and middle levels, though there’s a need to further organise and develop digital workforces

Over the last decade, many governments have created central digital teams to drive progress and support departments. And, offering good training, flexible working and a sense of purpose, they have built large workforces of junior digital professionals within line departments.

The creation of these departmental delivery teams has represented a deliberate attempt to shift away from the discredited model under which government defined the IT system it required, then commissioned a big IT firm to build it. This approach not only failed to reliably produce workable IT systems (see comments on project management, above), but also left governments without in-house skills or capacity — undermining the quality of commissioning, and stripping away any ability to build new services independently.

“For years, we were doing a lot of outsourcing,” commented one interviewee. “In the last six years or so, government has brought some of the engineering capabilities in-house. And because we’ve in-sourced, we were able to build certain capabilities in a short space of time — very visibly improving people’s lives during the pandemic.”

To maintain and develop governments’ digital delivery capabilities, however, further action is required to build career pathways, strengthen skills, and manage digital professionals across government as a single workforce. “We look at the UK with envy, in terms of some of the capacity-building and upskilling programmes run across the civil service,” said one interviewee.

Finding 6: Constrained pay for top digital roles leaves many civil services unable to recruit or retain the quality of talent required to lead transformation

Civil services can build strong digital workforces, creating a pipeline of talented managers — but at the most senior levels, pay disparities with the private sector widen to the point where many governments struggle to compete.

“We pay very competitively for the junior staff, and competitively enough to get a fair number of mid-level staff,” said one interviewee. “But we’re absolutely not competitive when it comes to the most senior staff — who are the people we need the most.” Another interviewee was equally concerned: “The private sector is now using the public sector as a kind of careers breeding ground, and we’re seeing people shift really rapidly,” they said. “We think there’s a huge war for talent emerging over the next 5–8 years.”

The problem seems particularly acute in countries with strong domestic technology industries, and in those where pay constraints or caps — often linked to the incomes of political leaders — limit the salaries that civil service bodies can offer. Imposed for political and presentational reasons, in our view such caps cost far more than they save.

Where departments can’t fill leadership positions on a permanent basis, for example, they often install interim managers — but temporary staff lack the authority or mandate to produce effective policies or drive progress, so departments end up treading water. Where senior leaders lack the skills and expertise to manage transformation programmes, they must fall back on consultancies: this is expensive in the short term, noted one interviewee, and creates “dangers around quality and capture and incentives.” And where departments end up promoting in-house staff beyond their abilities, they can end up investing large sums in digital programmes that do not come to fruition.

Political leaders might find it uncomfortable to accept higher pay for senior digital leaders, but there’s evidence that other civil service professionals are in favour: in a recent survey carried out by Global Government Forum for NTT DATA UK, an overwhelming majority of non-digital UK senior civil servants supported greater pay flexibilities for digital leaders. Until governments get past this highly political obstacle, many will continue to experience delays in digital transformation, while wasting far larger sums of money — in poor project management and failed reform programmes, for example — than they save via pay constraints.

Finding 7: Departmental leaders and ministers often lack the understanding and commitment to drive digital transformation

Digital leaders may be charged with transforming systems and services — but those operations are almost always controlled by others. So no digital leader can achieve their goals without the active support and participation of other senior managers, particularly ministers and departmental leaders. And all of our interviewees felt that, while these groups are nowadays taking greater ownership of the digital agenda, they remain poorly prepared to understand and drive digital transformation.

In some of the countries we studied, national political leaders have a good understanding of the digital agenda; this does help in promoting digital reforms, interviewees said. But such knowledge is equally important among departmental ministers, where daily decisions are made about organisational reform and service delivery. And among the civil servants leading departments — whose active engagement is essential to digital progress — very few are genuine champions of digital transformation.

This is not the fault of these leaders, but rather of systems of performance management, incentives and promotion that actively weed out people with the skills and behaviours required to lead digital transformation. In most countries, it’s political and policy skills — rather than technical expertise — that hoist people to the top of the ladder: a talent for providing service continuity, avoiding media interest or managing political or interdepartmental tensions provide a far greater career boost than the ability to conceive and enact digital reforms.

So digital bosses, commented one interviewee, end up working with departmental leaders who’ve “spent their entire careers being reflexively liability-conscious and risk-averse — because that’s how they got to be [departmental leaders] — and asking them to do the unthinkable and embrace change. It is the wrong cohort to try to get to lead such an operation.” Such leaders, they added, “know that their organisations should be more user-centred and more agile, but they’re not quite sure what that means and they don’t understand how to get there — given the way they’ve been taught to do business, and all the other pressures in their world.”

Exacerbating these cultural problems, departmental leaders considering digital reforms often face an unappetising mix of rewards and risks. When central digital teams ask them to adopt a platform or shared service, commented another interviewee, “they own the operational accountabilities; they own the performance risk. If I say: ‘We’ve got to do this,’ and it impacts on their ability to deliver, then that’s on them.” So departmental leaders face being held responsible if a new digital service — built and controlled elsewhere — fails, while the incentives to participate often comprise little more than a promise of cost savings and some praise from digital leaders. Hence the need for stronger central management of digital targets and goals, with departmental leaders held accountable against them — rebalancing their risk/reward calculation to favour greater ambition on digital transformation.

Ultimately, the responsibility for driving digital transformation cannot be successfully delegated from departmental to digital leaders — and in countries where this is recognised, progress is much more rapid. “The ministries’ digitalisation is an executive accountability, and that message has been sent loud and clear” to departmental leaders, commented an interviewee from one of the best-performing nations. “At that level, we are emphasising that it is your accountability to drive this; the CIO is there to enable and support you.”

Case study: workforce development in the UK

A decade ago the UK government began digitising paper-based services, and quickly recognised the need to build up in-house expertise and capacity. But digital developers were scarce, and private business absorbed much of the supply. By 2016 civil service bodies were openly competing with each other to attract skilled staff, creating both grade and pay inflation. There was little consistency in digital job descriptions or pay across government, while departments were experiencing rapid staff turnover and high salary costs.

Keen to create rational, cross-government career paths for digital staff and to end this damaging internal competition, the Government Digital Service (GDS) team created the first roster of the civil service’s 17,000 digital, data and technology (DDaT) professionals, then ran hundreds of workshops to develop a DDaT profession capability framework . This defined 37 digital roles, and specified the expertise and experience required for staff within each role to reach a set ‘competency’ deciding their seniority. Each competency was further broken down by skill level, from ‘awareness’ to ‘expert’. The entire DDaT workforce was then assessed, with each individual being allocated a role, a competency level, and a skill level within that competency; these in turn decided their salary.

With the profession’s roles and requirements clearly defined, the government’s network of digital academies could focus on meeting the workforce’s identified needs. This structured approach has provided consistency around salaries, ensured effective and targeted skills development, supported sensible career progression across the civil service, and eased departments’ recruitment and retention problems.

Conclusions

In all our interviewees’ countries, digital leaders have made progress over recent years — particularly on digitising citizen-facing services, building skilled workforces, and demonstrating the power of digital and data technologies. But behind these outward similarities, there is a substantive gap between those nations well advanced in identifying and putting in place the foundations of effective digital transformation, and those much further behind on this journey.

Within the former group, digital leaders are equipped to realise ever more of the potential value of their governments’ data assets, while rapidly rebuilding public services around a smart, accessible, citizen-centred model. But leaders within the latter set of nations face far more obstacles and costs in delivering individual digital projects, and lack the cross-government leadership, policies and platforms required to embed new digital services within a coherent, unified public services offer.

As well as highlighting a number of these foundational conditions, our research revealed some of the reasons why their prevalence is so patchy. In some cases, control over the changes required to put these essential building blocks in place lies well outside the digital space; and here Global Government Forum — whose global audience spans the civil service functions and specialisms — can best serve public servants by supporting discussions and partnerships across departmental and professional boundaries.

One common perception among CIOs, for example, is that digital programmes demand the wholehearted engagement and support of departmental leaders — who, most felt, tend not to actively drive reforms forward. Another strong message concerned the cross-government systems governing processes such as procurement, spending approval and project management, which often fail to recognise the specific needs of digital technologies. To strengthen mutual understanding, explore the barriers to progress, and identify reforms that can reconcile competing interests and support faster progress on digital transformation, Global Government Forum will introduce dedicated sessions at two of our key events — considering the roles of departmental leaders at the Global Government Summit, and commercial and budgetary systems at the Government Finance Summit.

In other cases, countries’ constitutional, cultural, political and technological legacies are so diverse that, while digital leaders’ goals remain similar, their starting points — and thus the tasks required to realise those goals — have little in common. Here, CIOs will benefit most from engaging with those whose circumstances broadly mirror their own.

The most obvious example concerns the creation of digital ID systems. Nations that operate a national ID system have a relatively straightforward route to developing a digital version, building it around the unique citizen identifiers underpinning their existing systems. These countries’ CIOs have a huge amount to learn from one another — addressing topics around delivery, uptake and international compatibility, for example — but much less to offer those starting from scratch in creating a cross-government citizen ID system.

Those lacking a national ID system face much more fundamental questions around design and implementation. Around the world, they’ve approached the challenge in many different ways, building up huge experience in what works — and here mutual support can be enormously helpful in cutting costs, shortening timescales and averting mistakes. In October 2022, Global Government Forum will hold parallel events serving CIOs in these two very different situations .

Finally, our research identified a set of important issues where all of our interviewees face comparable challenges as they work to put these digital fundamentals in place. One example is the need to ensure that digital ‘visions’ go beyond painting a picture of the future, explaining exactly how governments will get from here to there — and thus mapping out a realistic path to delivery. Another concerns skills, where most countries could benefit from greater professionalisation and the development of organised digital and data ‘functions’ — creating strong career pathways, improving recruitment and retention, and fostering a more flexible workforce.

Global Government Forum will run international workshops on these topics, examining ‘Vision and planning’ in March 2022 and ‘People and skills’ in April ; both events will help shape the agenda at next year’s Government Digital Summit . And alongside this work, we’ll gather feedback on our research findings and consider developing this pilot project: the options include expanding participation to incorporate perspectives from a much wider range of countries, and conducting ‘deep dives’ into particular aspects of the topic.

Meanwhile, we hope that the insights and messages in this report prove useful to senior civil servants working in the digital sphere and beyond it. The foundations of digital transformation look broadly similar around the world; and while the task of building them may vary from country to country, those underlying commonalities make digital one of the most fruitful fields for stronger international learning, exchange and collaboration.

For digital leaders — both at the centre of government, and in departments — strengthening civil servants’ use of technologies can seem a lonely task, set about by tensions with other agendas, professions, teams and departments. But you are not alone: in every country, your peers are trying to reach a similar destination. There’s a huge amount to gain by comparing notes along the way: as the Turkish proverb says, ‘No road is long with good company.’

Originally published at https://digital.globalgovernmentforum.com.