institute for health transformation (InHealth)

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Chief Researcher, Editor and CSO (Chief Strategy Officer)

Januaray 26, 2023

The Lancet

Tieble Traore, Sarah Shanks,Najmul Haider, Kanza Ahmed, Vageesh Jain, Simon R Rüegg, Ahmed Razavi, Richard Kock, Ngozi Erondu, Afifah Rahman-Shepherd, Alexei Yavlinsky, Leonard Mboera, Danny Asogun, Timothy D McHugh, Linzy Elton, Oyeronke Oyebanji, Oyeladun Okunromade, Rashid Ansumana, Mamoudou Harouna Djingarey, Yahaya Ali Ahmed, Amadou Bailo Diallo, Thierno Balde, Ambrose Talisuna, Francine Ntoumi, Alimuddin Zumla, David Heymann, Ibrahima Socé Fall, Osman Dar

January 19, 2023

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed faults in the way we assess preparedness and response capacities for public health emergencies.

Existing frameworks are limited in scope, and do not sufficiently consider complex social, economic, political, regulatory, and ecological factors.

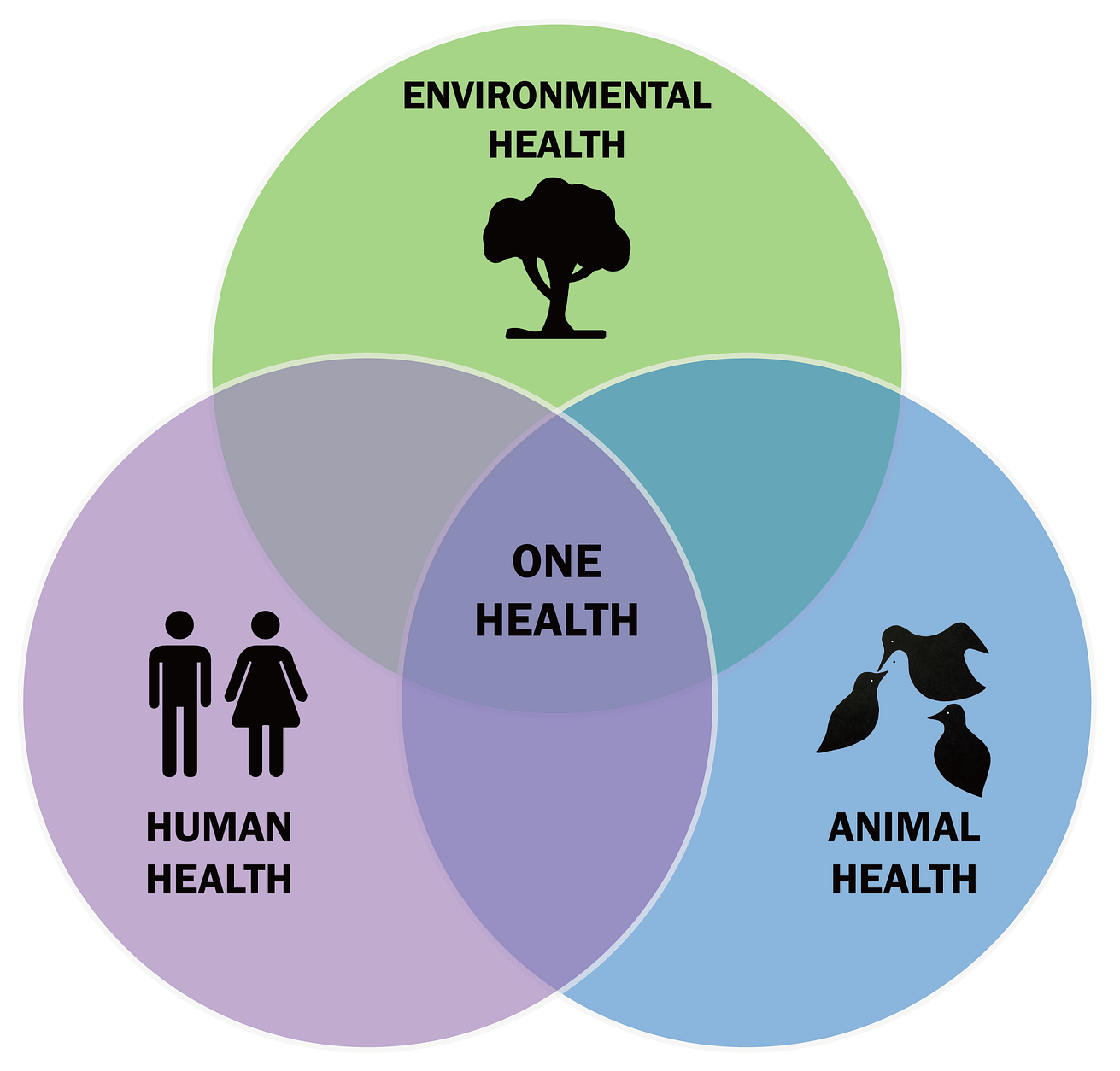

One Health, through its focus on the links among humans, animals, and ecosystems, is a valuable approach through which existing assessment frameworks can be analysed and new ways forward proposed.

Although in the past few years advances have been made in assessment tools such as the International Health Regulations Joint External Evaluation, a rapid and radical increase in ambition is required.

- To sufficiently account for the range of complex systems in which health emergencies occur, assessments should consider how problems are defined across stakeholders and the wider sociopolitical environments in which structures and institutions operate.

- Current frameworks do little to consider anthropogenic factors in disease emergence or address the full array of health security hazards across the social–ecological system.

- A complex and interdependent set of challenges threaten human, animal, and ecosystem health, and we cannot afford to overlook important contextual factors, or the determinants of these shared threats.

Health security assessment frameworks should therefore

- Ensure that the process undertaken to prioritise and build capacity adheres to core One Health principles

- and that interventions and outcomes are assessed in terms of added value, trade-offs, and cobenefits across human, animal, and environmental health systems.

Key messages

- The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed weaknesses of the assessment frameworks evaluating preparedness for national, regional, and global public health crises.

- Although crossovers exist between assessment tools and indicators, these frameworks are undermined by their inability to sufficiently consider the role and complexities of social, economic, political, regulatory, and ecological factors that enable effective One Health preparedness and response.

- Matrix models for capacity assessment of health security will be needed, which monitor and assess the achievement of outcomes, as well as ensure that the processes undertaken reflect the One Health approach and adhere to its underlying principles.

- For existing instruments undergoing reform (eg, the International Health Regulations Monitoring and Evaluation Framework and the Joint External Evaluation tool) and for new initiatives such as the global One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022–26), it will be important to ensure that the processes of implementation comply with One Health principles and that intervention and outcome assessments include analysis of added value, cobenefits, and trade-offs across sectors.

- Global assessment and indicator frameworks have historically been developed to assess the capacity of countries to detect, prevent, and respond to public health events.

- However, these tools have not produced reliable assessments of the effects and risks of various interventions, particularly the wider effects of response strategies on other sectors.

- Although quantitative data are easier to present for summary comparisons, they do not consider context, which might require the inclusion of qualitative information and participatory engagement of local communities most affected by crises.

- Existing assessment and indicator frameworks should be reviewed via a whole-system, all-hazards approach, taking into account the lessons learnt from previous and current public health crises, and acknowledging the political, social, economic, and ecological complexities facing countries at both national and subnational levels.

- There is a need to rationalise and harmonise the plethora of existing frameworks to enable a sustainable approach.

- Furthermore, agencies and countries should have the ability to identify and select hazards relevant to One Health on the basis of local risk to enable pragmatic solutions and monitoring.

- A sustainable assessment process needs to be developed to reduce the burden on countries, which are expected to simultaneously respond to existing public health crises and prepare for future incidents, while reporting on current progress against several hundred indicators with little financial investment and low-resource capacities.

- Despite being a potential political impetus to act, assessment frameworks and indicators should not be used as mechanisms to make spurious inter-country comparisons because of the differing contexts characterising each country.

- Focus should instead be on individual countries and regions to establish baseline assessments of capacity by use of harmonised tools and indicators to monitor self-progress and inform future policy and investment.

Despite being a potential political impetus to act, assessment frameworks and indicators should not be used as mechanisms to make spurious inter-country comparisons because of the differing contexts characterising each country.

Focus should instead be on individual countries and regions to establish baseline assessments of capacity by use of harmonised tools and indicators to monitor self-progress and inform future policy and investment.

INFOGRAPHIC

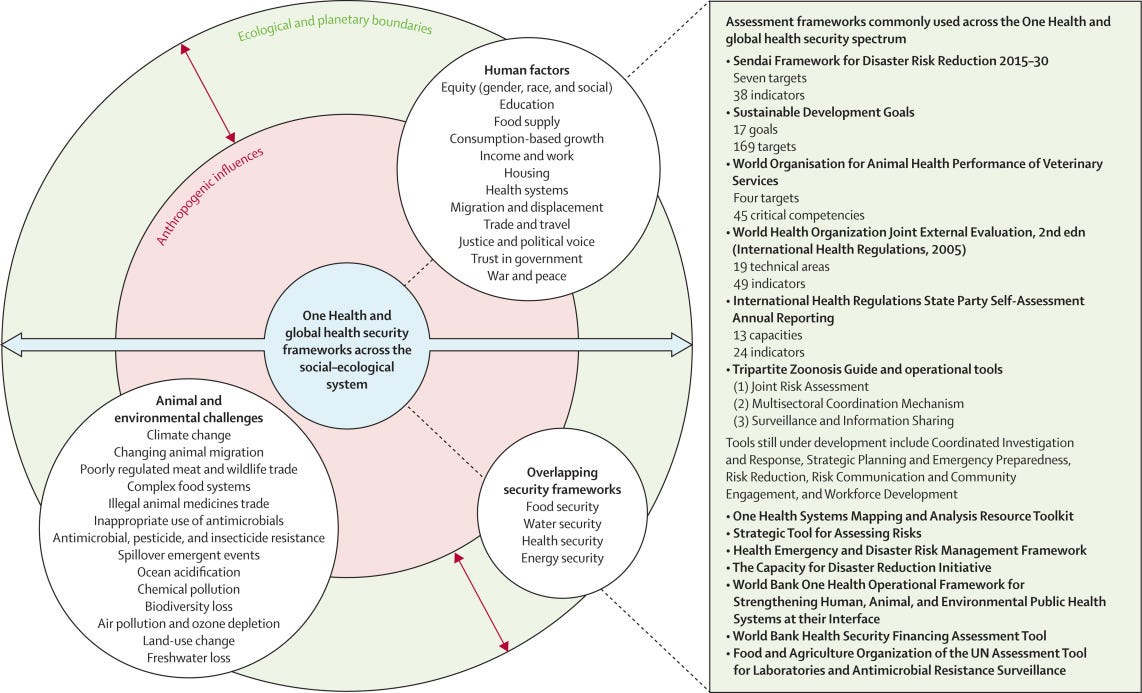

Figure: Commonly used UN and World Bank assessment tools and frameworks for global health security and One Health causing pressure on ministries and national public health institutes

- The green circle represents the ecological and planetary boundaries, whereas the red circle corresponds to anthropogenic influences, including economic, political, cultural, social, regulatory, and technological.

- The red arrows indicate the interdependence and interconnection of anthropogenic influences (ie, factors influencing each other in a systemic model rather than a linear model) and their potential to result in breaches of the ecological and planetary boundaries, thus negatively affecting health security.

- The smaller circles correspond to interacting factors and conditions that are interdependent and influence global health security.

Conclusions [excertp from the full version]

We are currently facing unprecedented challenges that threaten human and animal health and environmental sustainability in complex and interdependent ways. We cannot afford to overlook important contextual factors, or the determinants of these socioeconomic and political contexts in which threats to human, animal, and planetary health emerge and are sustained.

Radical shifts in our thinking are needed, away from models that are based on the conceptualisation of public health threats as apolitical, simplistic, linear, or additive disease interactions among humans, animals, and the environment. Greater recognition of the substantial number and diversity of actors and agents involved is needed, many of whom are not within the human and veterinary public health sectors.

The narrow framing of core competencies (eg, food safety equating to foodborne outbreaks and surveillance with no consideration of access to food and water or nutrition security) as the measures needed to prevent, detect, and respond to public health threats has diverted attention from the breadth of socioeconomic, political, regulatory, and ecological factors that are driving the cycle of crises that threaten health across all sectors.

We should reflect on the assumptions made to develop performance frameworks and analyse more critically the problem definitions being adopted and the solutions being proposed. The issue that should be prioritised is not a shortage of frameworks, indicators, and metrics but rather a scarcity of transformational thinking about how, why, when, and by whom such tools are developed, who benefits, who is disadvantaged, and how to mitigate inequity. Technical working groups with involvement of regional bodies, UN agencies, and, crucially, civil society organisations and communities themselves, are required to harmonise the many existing frameworks in a sustainable and coherent way. Calls have already been made to integrate existing frameworks and targets such as through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets as a means of addressing the imbalance currently afflicting the One Health approach. However, adopting pre-existing indicators simply because they exist does not allow for crucial examinations of the underlying assumptions, barriers, and enablers associated with the achievement of the required transformational actions. With revisions of the current IHR MEF underway, including of the JEE, and the launch of the global One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022–26), a real opportunity exists to ensure future monitoring and evaluation tools for health security properly reflect application of the One Health approach.

Matrix models of assessment are therefore necessary, which assess both the process of implementation — ensuring One Health principles are being adhered to — and evaluate interventions and outcomes more holistically (ie, in terms of added value and trade-offs across the human, animal, and environmental sectors).

Furthermore, there is an urgent need to reduce the assessment burden on countries.

Countries are currently at risk of duplicating capacity assessments, thus increasing the reporting burden and potentially affecting assessment and reporting quality, with knock-on implications for the implementation of recommendations.

The explicit reason for emphasising the importance of the environmental sector in global health security is justified in the World Bank’s One Health Operational Framework for Strengthening Human, Animal, and Environmental Public Health Systems at their Interface:

“The importance of the environment for human well-being and economies is well established (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment). Ecosystems provide critical public health-promoting services, and thus ecosystem degradation may present consequences for human health.”

The formal inclusion of UNEP into the Tripartite is a welcome attempt to remedy this omission and should allow for sufficient prioritisation of, and investment in, wildlife and environmental science. Community participation has been shown to provide powerful insights to frame health challenges at the human–animal–environment interface.

By framing One Health as a contributor towards sustainable health outcomes, community participation could then become an important aspect to improve the relevance, and enable stewardship, of health policies for all.

A holistic, One Health approach could be compromised by the absence of indicators for community participation, or by the insufficient consideration of trust between the government and the population (panel 2).

Although all-hazards approaches are useful for taking into account the complex interactions among human, animal, and environmental health, experts on disaster risk reduction working with the experts on health security should support NPHIs to assess and categorise which hazards are most important and what interventions are most likely to be effective in mitigating risk. Such an approach would allow countries to prioritise and focus on immediate concerns and be clear on which sector (human, animal, or the environment) should lead on which hazard. It also enables the selection of relevant indicator frameworks to suitably assess capacity and development. Furthermore, this approach entails an important shift away from the use of assessment frameworks as a tool for inter-country comparison (and competitiveness) and moves the focus on the establishment of baselines and measures of self-progress in preparedness and health capacity.

Indicators can facilitate a reconceptualisation of knowledge and the assessment process provides an opportunity to further understand the wider societal issues and the complex dynamics of human, animal, and ecosystem health that affect the ability to mitigate global public health threats. By embracing complexity, assessment frameworks can be more effective and equitable.

As the world emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic, important decisions will have to be made in terms of which paths and which tools (eg, indicators, frameworks, and measures) are best to improve our collective interventions addressing the health of people, animals, and the planet on which they depend.

Independent of whether future actions are implemented by use of a One Health approach or through other means, complexity, detail, and debate that involves challenging old assumptions and welcomes new ideas should all be at the core of establishing an effective, equitable, and dynamic approach to achieving health for all living creatures and the planet.

Originally publish at https://www.thelancet.com

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY [by the Editor of the blog]

We are facing unprecedented challenges that threaten human, animal, and environmental health in complex and interdependent ways.

- A shift in thinking is needed away from models that are based on simplistic, linear, or additive disease interactions among humans, animals, and the environment.

- Greater recognition of the substantial number and diversity of actors and agents involved is needed, many of whom are not within the human and veterinary public health sectors.

The narrow framing of core competencies has diverted attention from the breadth of socioeconomic, political, regulatory, and ecological factors that are driving the cycle of crises that threaten health across all sectors.

- Matrix models of assessment are necessary which assess both the process of implementation and evaluate interventions and outcomes more holistically.

There is an urgent need to reduce the assessment burden on countries.

- The formal inclusion of UNEP into the Tripartite is a welcome attempt to remedy this omission and should allow for sufficient prioritization of, and investment in, wildlife and environmental science.

- Community participation is important to improve the relevance, and enable stewardship, of health policies for all.

- Indicators can facilitate a reconceptualization of knowledge and the assessment process provides an opportunity to further understand the wider societal issues and the complex dynamics of human, animal, and ecosystem health that affect the ability to mitigate global public health threats.

By embracing complexity, assessment frameworks can be more effective and equitable.

As the world emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic, important decisions will have to be made in terms of which paths and which tools are best to improve our collective interventions addressing the health of people, animals, and the planet on which they depend.

Independent of whether future actions are implemented by use of a One Health approach or through other means, complexity, detail, and debate that involves challenging old assumptions and welcomes new ideas should all be at the core of establishing an effective, equitable, and dynamic approach to achieving health for all living creatures and the planet.