This is a republication of the article “JPMorgan Is Still Trying to Fix Health Care”, with the title above.

Health, Care and Tech institute (HCTi)

for continuous health transformation

Joaquim Cardoso MSc*

Chief Researcher & Editor, and Chief Advisory Consulting

December 6, 2022

MSc* from London Business School

MIT Sloan Masters Program

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

JPMorgan Is Still Trying to Fix Health Care

An ambitious partnership with Amazon and Berkshire Hathaway fizzled, but the biggest US bank is giving it another shot — this time on its own.

Bloomberg

John Tozzi

6 de dezembro de 2022

Bill Wulf was in a meeting when he missed a call from Jamie Dimon.

As an internist and boss of a medical group in Columbus, Ohio, Wulf doesn’t often hear from the commanding heights of the US economy.

But when he rang back, the JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief executive officer immediately got on the line.

Wulf’s group had been involved in Haven, a venture led by JPMorgan, Amazon.com and Berkshire Hathaway that aimed to fix American health care with better technology and simplified benefits.

But the project had flopped, and Dimon wanted to understand where it had gone wrong.

Wulf’s group had been involved in Haven, a venture led by JPMorgan, Amazon.com and Berkshire Hathaway that aimed to fix American health care with better technology and simplified benefits. But the project had flopped, and Dimon wanted to understand where it had gone wrong.

“Why did we fail? What happened in Columbus?” Wulf recalls Dimon asking in the call two years ago.

The city is the bank’s second-biggest US employment hub, behind only New York, making it a crucial proving ground for Haven.

Wulf told Dimon that the effort had moved too slowly.

A virtual-care program, for instance, had attracted just 150 people in Ohio before the companies pulled the plug.

Wulf told Dimon that the effort had moved too slowly. A virtual-care program, for instance, had attracted just 150 people in Ohio before the companies pulled the plug.

Dimon was undeterred: “We want to do this again,” he told Wulf.

Dimon was undeterred: “We want to do this again,” he told Wulf.

For decades, corporate America has poured money into a health-care system that costs more each year without improving workers’ health.

JPMorgan’s bill is about $1.5 billion for its 270,000 employees and their families worldwide, and the workers kick in $500 million more.

Dimon, in his annual letter to shareholders this year, called the complexity of health care “staggering.”

JPMorgan’s bill is about $1.5 billion for its 270,000 employees and their families worldwide, and the workers kick in $500 million more. Dimon, in his annual letter to shareholders this year, called the complexity of health care “staggering.”

A 2019 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association estimated that …

… a quarter of the money the US spends on health care is wasted through failures such as overtreatment, overcharging, fraud and administrative complexity.

Prices vary dramatically, with, for instance, a frequently prescribed blood test ranging from $18 to $443, the Health Care Cost Institute reports.

Less expensive providers often have better records on safety and quality, but it’s tough for patients to get reliable information on that.

And as it’s designed now, the system encourages doctors to deliver more care, and costlier services, even when patients might benefit from a less aggressive approach.

And as it’s designed now, the system encourages doctors to deliver more care, and costlier services, even when patients might benefit from a less aggressive approach.

While individual companies — even the biggest US bank — are too small to change that dynamic, JPMorgan has formed a unit that aims to reshape the broader market for employer-sponsored health care.

Morgan Health has $250 million to invest in startups that the company thinks will improve the quality, affordability and equity of health coverage.

It’s working closely with the bank’s benefits team to bring new offerings to its own workers, starting in Ohio.

And it’s aligning with medical groups such as Wulf’s Central Ohio Primary Care to amplify its influence.

Morgan Health has $250 million to invest in startups that the company thinks will improve the quality, affordability and equity of health coverage.

With almost 500 physicians, Wulf’s practice serves about a quarter of JPMorgan’s workers in the area.

Wulf believes the factors that make America’s health-care system maddening for patients are the same things that make it so expensive for employers:

- (1) twisted incentives,

- (2) needless tests and procedures, and

- (3) missed opportunities to prevent illness.

“Waste is what leads to unnecessary patient suffering, and that’s what we should go about eliminating,” he says.

Wulf believes the factors that make America’s health-care system maddening for patients are the same things that make it so expensive for employers:

(1) twisted incentives, (2) needless tests and procedures, and (3) missed opportunities to prevent illness.

“Waste is what leads to unnecessary patient suffering, and that’s what we should go about eliminating,” he says.

The Morgan Health experiment will test the extent to which large employers can sway health-care markets.

Other companies have tried new, localized approaches, but they rarely reach the scale they aspire to, says Elizabeth Mitchell, CEO of the Purchaser Business Group on Health, a coalition of large employers such as Boeing Co. and Walmart Inc. focused on health-care innovations. (JPMorgan is not a member.)

“The challenge becomes, even when you find something that works, how do you move the entire market?” she says.

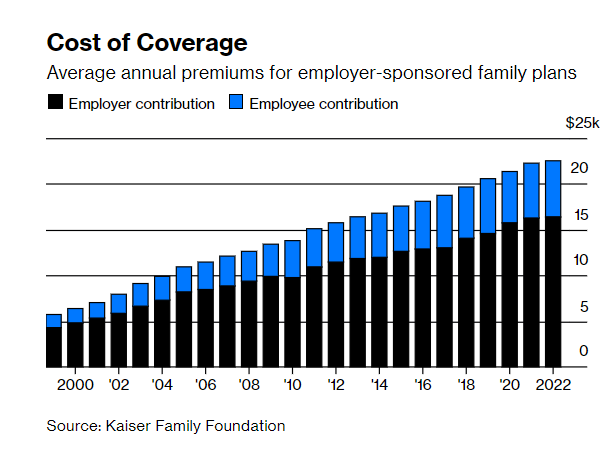

US employers and their workers spend $1 trillion a year on insurance for more than 150 million people.

In 2004, a General Motors Co. executive said the automaker paid more for health benefits than for steel.

Over the following decade and a half, US health expenditures roughly doubled, increasing twice as fast as incomes, spurring Warren Buffett to call health care “a hungry tapeworm on the American economy.”

Over the following decade and a half, US health expenditures roughly doubled, increasing twice as fast as incomes, spurring Warren Buffett to call health care “a hungry tapeworm on the American economy.”

To control costs, employers have tried

- health maintenance organizations that tightly manage care,

- high-deductible plans that are more expensive for people who get sick, and

- wellness programs — that put people with no symptoms through batteries of tests and screenings.

To control costs, employers have tried : (1) health maintenance organizations that tightly manage care, (2) high-deductible plans that are more expensive for people who get sick, and (3) wellness programs that put people with no symptoms through batteries of tests and screenings.

They’ve placed medical clinics on corporate campuses and tested myriad apps and programs targeting discrete problems such as diabetes or back pain.

While some approaches show small-scale success, the relentless rise of medical expenses each year drains company finances, public-sector budgets and workers’ wages.

The cost of health insurance, shared between companies and employees, is now $22,463 for the average family. Every year.

The cost of health insurance, shared between companies and employees, is now $22,463 for the average family. Every year.

By the time Haven wound down, Covid-19 had forced companies to face new health-care problems.

Beyond the logistics of testing and vaccination, the pandemic amplified a national mental health crisis.

And George Floyd’s murder brought fresh awareness to long-standing health disparities that disproportionately cut Black lives short.

Beyond the logistics of testing and vaccination, the pandemic amplified a national mental health crisis.

And George Floyd’s murder brought fresh awareness to long-standing health disparities that disproportionately cut Black lives short.

Not long after Dimon called Wulf, the CEO assigned a top lieutenant, Vice Chairman Peter Scher, to lead the renewed effort on health care.

At first, Scher wasn’t convinced it was worth another shot. “There are a lot of things we could be spending our time on,” he says.

“I was perfectly prepared to go back to Jamie and the operating committee and say, ‘Listen, it was a good try.’ ”

As record numbers of workers quit across the economy, Scher recognized that for the bank to compete, delivering better benefits was an imperative, and that helped him get over his initial doubts about the initiative.

The pandemic had exposed inequities in the health-care system — and among the bank’s staff.

“How do we think about our lower-wage employees, people who work in the branches who can’t step out and sit on hold with the insurance company for two hours?” he says.

“How do we think about our lower-wage employees, people who work in the branches who can’t step out and sit on hold with the insurance company for two hours?” he says.

Scher brought on Dan Mendelson, an industry veteran who’d founded and sold an influential Washington, DC, consulting firm called Avalere Health.

A skeptic of Haven, Mendelson spent three months in early 2021 helping the bank develop a playbook for Morgan Health aimed at succeeding where the earlier effort had failed. Then he signed on to lead it.

Without other companies involved, it could be more nimble, with clearer governance and a sharper focus, Mendelson says.

Without other companies involved, it could be more nimble, with clearer governance and a sharper focus, Mendelson says.

Morgan Health now has about 30 employees and recently hired Cheryl Pegus, Walmart’s top health and wellness executive.

The bank has set a five-year goal to reduce unnecessary hospital trips, improve management of conditions such as diabetes, lower financial barriers to care, and narrow health disparities across race, income and geography.

To get there, Mendelson says, the company has to encourage doctors to achieve measurable results rather than reward those who prescribe the greatest number of tests and procedures.

“What we’re doing is flipping the incentives,” he says. “The providers that are working with us are responsible for improving the health of our employees.”

The bank has set a five-year goal to reduce unnecessary hospital trips, improve management of conditions such as diabetes, lower financial barriers to care, and narrow health disparities across race, income and geography.

To get there, Mendelson says, the company has to encourage doctors to achieve measurable results rather than reward those who prescribe the greatest number of tests and procedures. “What we’re doing is flipping the incentives

On the outskirts of Columbus, in an expanse of office parks and shopping centers known as Polaris, 10,000 JPMorgan employees occupy a broad four-story office complex on a former soybean field.

It houses one of the bank’s three fixed-income trading floors (along with New York and London), the largest corporate solar panel array in the US outside Apple Inc.’s headquarters and one of Ohio’s busiest Starbucks.

The Polaris campus, with 2 million square feet of office space, was a major center for Bank One, the company Dimon led before its merger with JPMorgan Chase.

Across an atrium from the Starbucks is a new clinic that’s a linchpin of the Morgan Health strategy.

While the bank has long had medical centers in its offices for urgent needs and programs such as flu shots, the clinic is meant to be something different:

- a full-service practice where employees can develop long-term relationships with primary-care providers,

- wellness coaches,

- mental health providers and

- care coordinators.

While the bank has long had medical centers in its offices for urgent needs and programs such as flu shots, the clinic is meant to be something different:

(1) a full-service practice where employees can develop long-term relationships with primary-care providers, (2) wellness coaches, (3) mental health providers and (4) care coordinators.

JPMorgan has opened five clinics in the Columbus area — three in the bank’s offices and two nearby for family members on the company plan.

Those will also be open to other employers who want to sign on. The goal is to “identify high-risk patients and then bubble-wrap them,” Wulf told Ohio business leaders over lunch at the JPMorgan campus in October. “How do we keep you out of the hospital?”

Those will also be open to other employers who want to sign on. The goal is to “identify high-risk patients and then bubble-wrap them,” , … and keep them out of the hospital?”

The clinics are operated by a joint venture between Wulf’s Central Ohio group and Vera Whole Health Inc.

In its first deal, Morgan Health last year invested $50 million in Vera, and it’s the only portfolio company that’s also signed JPMorgan as a client.

Other investments include

- a primary-care-centered health plan called Centivo;

- home-testing company LetsGetChecked; and

- Embold Health, which provides data on physician performance.

Vera operates clinics for other employers such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Seattle Children’s Hospital, and it aims to address mental well-being and social circumstances as well as physical health.

Vera operates clinics for other employers such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Seattle Children’s Hospital, and it aims to address mental well-being and social circumstances as well as physical health.

Vera considers each visit an opportunity to change the trajectory of a patient’s health, even if the person shows up simply to get a cut bandaged.

At the new clinics in Columbus, all appointments are booked for at least 30 minutes and many are an hour, giving clinicians time to understand people’s concerns and help them manage chronic diseases.

To build long-term relationships, patients generally see the same practitioner for each visit — the kind of care that’s been squeezed by pressure to cram the schedule with as many patients as possible.

“Especially that younger generation, they’ve never seen good primary care,” says Marla McLaughlin, Vera’s associate chief medical officer. “They don’t even know what they’re missing.”

At the new clinics in Columbus, all appointments are booked for at least 30 minutes and many are an hour, giving clinicians time to understand people’s concerns and help them manage chronic diseases.

The bank’s agreement with Vera ties payments to health goals.

It aims for progress on measures such as controlling high blood pressure, keeping diabetics’ blood sugar levels in check, and providing people with proper cancer screenings.

And Vera will be rewarded for avoiding emergency room visits and steering patients to more appropriate — and less costly — alternatives.

JPMorgan declines to discuss financial details of the effort but says the motivation is improving the health of workers and their families, not cutting costs.

If it works, though, the bank says the investment in prevention and primary care will reduce high-cost services and hospital stays, ultimately leading to meaningful savings.

If it works, though, the bank says the investment in prevention and primary care will reduce high-cost services and hospital stays, ultimately leading to meaningful savings.

Subodh Keskar visited one of the new Columbus facilities in August.

A product analyst who works on systems that automatically send out replacements when Chase customers lose their credit cards, he fainted last summer while on vacation in India and spent a night in a hospital there.

Back in Ohio, the 45-year-old called more than 15 doctors from his insurance plan’s directory before getting an appointment six weeks out.

Then he heard about the new on-site clinic, which had openings right away.

The doctor spent more than an hour with him and referred him to a top hematologist. When test results came back, his Vera doctor got on the phone to discuss them.

“How many times you call a doctor’s clinic and the doctor actually talks to you?” Keskar says, smiling broadly as he recounts the story.

He seemed to be healthy, and the doctors thought the fainting was unlikely to recur. But he was instructed to call his Vera physician if anything seemed off. Keskar is converted. “I told my doctor, I’m your permanent patient,” he says. “Anything happens, I’m coming here.”

To meet Morgan Health’s loftiest goals, the bank will have to replicate that experience, and not just for its own workers.

The Vera clinics in Ohio saw almost 1,700 patients in the three months after opening.

JPMorgan hopes other employers around Columbus will sign on, potentially putting more pressure on local medical providers to shift their practices (and drawing more business for Vera).

Beyond Ohio, the bank is looking for like-minded medical groups in markets where it has lots of workers such as New York, Chicago and Dallas.

It will be a years long effort that could sputter out like Haven.

But if it succeeds, Morgan Health’s strategy will offer a road map for other employers, says Ron Williams, a former CEO of insurer Aetna Inc.

He’s now an operating adviser at private equity firm Clayton, Dubilier & Rice, Vera’s majority owner, and chairs Vera’s board.

If JPMorgan can rein in costs while improving workers’ health, other companies “will watch what happens and be fast followers,” Williams says.

If JPMorgan can rein in costs while improving workers’ health, other companies “will watch what happens and be fast followers,” Williams says.

Haven, of course, raised similar hopes.

While Williams is optimistic, he’s also realistic: “If it were easy,” he says, “it would’ve been done.”

While Williams is optimistic, he’s also realistic: “If it were easy,” he says, “it would’ve been done.”

Originally published at https://www.bloomberg.com

Names mentioned

Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan

Bill Wulf , internist and boss of a medical group in Columbus

Dan Mendelson, Avalere Health.

Cheryl Pegus

Wulf’s Central Ohio group

Vera Whole Health Inc.

Subodh Keskar

Marla McLaughlin, Vera’s associate chief medical officer

Elizabeth Mitchell, CEO of the Purchaser Business Group on Health, a coalition of large employers such as Boeing Co. and Walmart Inc.

Ron Williams, a former CEO of insurer Aetna Inc.