CGDev – Center for Global Development

Srobana Ghosh, Abha Mehndiratta, Lorna Guinness, Y-Ling Chi, Peter Baker, Javier Guzman and Hiral Anil Shah

May, 24, 2021

India, like Brazil, Uruguay, and the UK, has reported a higher death toll from its second wave of COVID than its first, demonstrating the perils of failing to prepare when cases are low. Neighbouring countries (Nepal, Thailand, Bhutan, Sri Lanka) followed a similar path and are all now experiencing a steep rise in cases. John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, recently stated that India’s COVID crisis is a wake-up call for Africa, but really it is a wake-up call for the rest of the world too.

While cases are low, all countries should make the most of their resources to prepare for a possible resurgence. In this blog, we provide seven recommendations on how to do this, drawing from India’s experience.

- Follow the science and establish epidemic response processes, task forces, and institutional structures so governments can act promptly before cases rise too high

- Actively monitor epidemiological and environmental indicators to detect local outbreaks

- Invest in expanding testing

- Start exploring the use of digital solutions to improve health surveillance

- Engage regulators and establish evidence-based vaccination plans for efficient vaccine distribution and allocation

- Strengthen essential health services for COVID and non-COVID patients

- Communicate strongly and clearly with the public

1. Follow the science and establish epidemic response processes, task forces, and institutional structures so governments can act promptly before cases rise too high

Governments that ignore or delay acting on scientific advice miss a crucial opportunity to control the pandemic. For example, India’s leaders were not prepared to initiate a response as its COVID-19 taskforce had not met for months before the second wave.

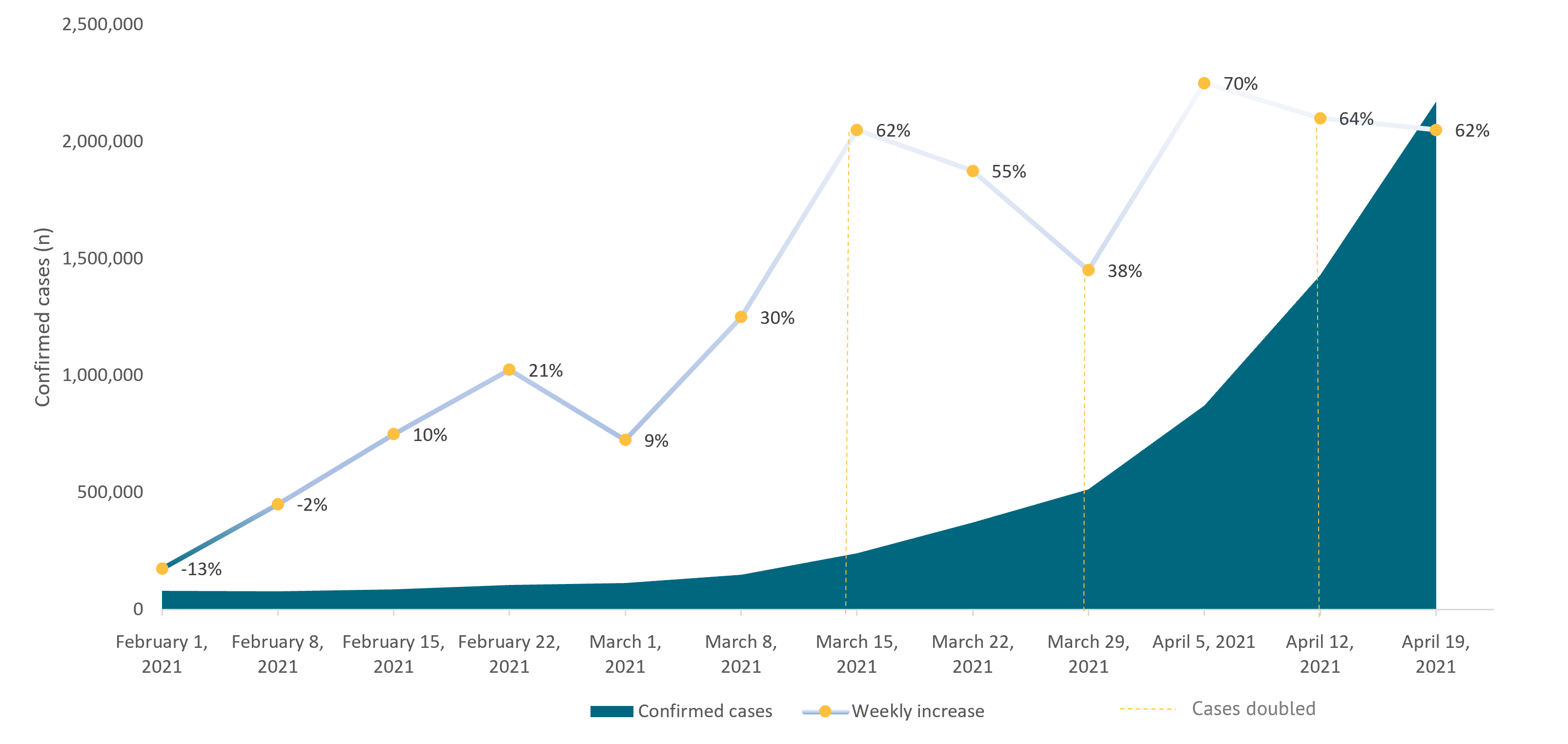

It’s important to remember that the speed of the growth in COVID-19 infections is proportional to the size of the population infected. If the speed of growth is high, it won’t be long before infections are out of control and the health system is overwhelmed, as happened in India (see Figure 1). It is imperative for countries to act as early as possible when cases begin to tick upwards to prevent exponential growth in transmission.

Figure 1. Number of cases in India over a 12-week period and the associated weekly percentage increase

Source: WHO

Decision-making during a pandemic is complex: it involves tremendous pressure; requires multiple stakeholders; and relies on information that is flawed, uncertain, proximate, or sparse. Countries should, therefore, make the most of the non-emergency period (when cases are low) by setting up processes (e.g., a crisis response plan), task forces (e.g., oxygen task forces), and institutional structures (e.g., SAGE in the UK, which provides timely and coordinated scientific advice to national decision-makers) to guide a swift and timely response. This is the time to develop a sustainable lockdown plan in consultation with key stakeholders that can be tolerated by the local economy and community.

These actions can ensure that all departments at each level of government know their role and responsibility in the epidemic response, are empowered to initiate processes based on up-to-date evidence, and are held accountable.

Importantly, these institutional processes and structures must remain alert and responsive to any change in data, such as an increase in infections or the detection of new virus strains. This will be facilitated with active monitoring.

2. Actively monitor epidemiological and environmental indicators to detect local outbreaks

Governments must ensure that they have active surveillance systems that are capable of detecting outbreaks and monitoring trends to enable rapid decision-making based upon up-to-date evidence. It is imperative that governments put in place systems to accurately record key indicators such as cases, hospitalizations, mortality, the infection rate, R0 (the number of new infections generated by each case), and seroprevalence in a timely manner. This is crucial for the early detection of rises in infections. Acting early is the only way to suppress a wave before it begins.

The pandemic has also highlighted concerns that epidemiological indicators are based on misreported or underreported data due to challenges in collection, collation, and transparency. Relying on hospitalisation and mortality data to estimate the size of the epidemic will have a time lag from onset of infection and will be further obscured as mild and asymptomatic infections typically go undetected.

Here, alternative data streams can be used to provide insight if epidemiological indicators are unreliable. For instance, live data on deaths can be challenging if civil registration and vital statistics systems are typically weak, but alternative sources of data—such as excess mortality statistics or community mortality indicators (e.g., burial data)—can be used to estimate the true burden of disease.

Wastewater surveillance can also be used as an early warning system to identify areas of outbreak. Monitoring sewage for traces of COVID-19 enables effective surveillance of entire communities, can capture asymptomatic disease, and can be used to estimate whether transmission is increasing or declining. This is particularly helpful in areas where timely COVID-19 clinical testing is underutilized or unavailable. One study anticipated that wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 could foreshadow new case reports by two to four days, which is much more timely than relying on hospitalizations or deaths. Countries like the UK, Australia, Germany, Italy, and Finland have already begun wastewater testing.

Importantly, using these indicators will help understand the spread of infection and areas where cases are rising. Sensitivity to any growth in cases will assist governments in acting early, however, each country will also need to strengthen their data systems and develop their own plan to measure these key indicators, based on the challenges of their own data infrastructure.

3. Invest in expanding testing

Early in its second wave, India experienced delays in COVID testing and showed high positivity rates, indicating that its testing limits had been maxed out. Scaling up testing is a necessary and fundamental component to identify the number of cases in a population, which can lead to rapid identification and containment of an outbreak. Testing in addition to effective contact-tracing, when implemented promptly, is known to help stop outbreaks. We have previously recommended ways for middle-income countries to effectively implement systems to test, trace and isolate.

If possible, countries should also consider the value of scaling up genomic surveillance to capture emerging variants that are associated with a higher transmission. This can be critical in timely detection of highly transmissible variants which can cause a surge in infections. For example, the double mutation variant was first detected in India in December 2020. However, it only became a dominant reported variant in March 2021 after several Indian states had reported surges in infections.

A key factor here was that India has only been sequencing just over 1 percent of samples, which is low compared to the UK, which was sequencing at 5-6 percent. Had India began scaling up genomic sequencing last year, this variant might have been identified and acted against earlier.

4. Start exploring the use of digital solutions to improve health surveillance

Digital technologies have been harnessed to support the public-health response by leveraging mobile data. For example, the UK (NHS COVID-19) and India (Aarogya Setu) created digital technologies for contact tracing, syndromic mapping, and self-assessment of COVID-19 through a mobile application. However, governments must ensure that such digital health technologies are scaled up only after the technology has shown effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

This pandemic has also shown that we have not learned how to make the most of the “data age” and too often have relied on traditional (yet highly imperfect) sources of data. Digital data streams (e.g., social media or tracking internet searches) could potentially help identify symptoms, areas of local outbreak or perhaps early detection of a rise in cases. Community mobility reports from Google data have also informed some governments on how national or local restrictions impact people’s movements (e.g., school attendance, park, train station traffic) throughout the pandemic.

While countries should explore digital solutions, the use of these data and digital technologies must always comply with legal, ethical, and clinical governance standards.

5. Engage regulators and establish evidence-based vaccination plans for efficient vaccine distribution and allocation

Despite India’s ambitious plan to scale up COVID-19 vaccination whilst cases were low, the Indian government did not pre-purchase sufficient quantities of vaccines to protect its own population. This meant that when the second wave hit, the speed of growth in infections outstripped the speed of vaccination delivery.

Under usual circumstances India has a strong track record of immunising large numbers of people every year (e.g., polio) with well-managed electronic systems to stock and track these vaccines, capacity in cold chain storage, and a large supply of auto-disabled syringes. However, resource constraints (e.g., human resources, PPE, transport) hobbled the government immunisation infrastructure’s COVID response. The Indian government also did not engage the regulatory authority to fast-track approvals or imports of vaccines (e.g., Pfizer), which left India dependant upon the Serum Institute of India and Bharat Biotech for all its doses. This has now led to several states in India running out of vaccine stocks, and only 2 percent of the entire population—and less than 10 percent of people over 60 years— have been fully vaccinated so far.

When cases are low, governments can:

- engage with regulatory authorities to fast track COVID-19 vaccine approvals

- establish evidence-based vaccination plans to show how national, regional, and local supply chains will efficiently deliver and administer COVID-19 vaccines

- improve information flow about vaccine supply and inventory across different levels of government

- invest in digital infrastructure to allow for appointment scheduling and registration systems

- prioritise vaccine allocation by aiming to reduce COVID-19 hospitalizations and mortality within the constraints of limited vaccine supply, and not maximize total vaccinations

- rapidly scale up human resources and cold chain capacity by exploring public-private partnerships

- reduce vaccine hesitancy through culturally sensitive and tailored risk communication and messaging

- set up strong pharmacovigilance infrastructure to collect, detect, assess, monitor, and prevent adverse effects

In addition to country-specific actions, the international community also plays an important role when cases are low through improving vaccine financing (e.g. ACT-A Accelerator), manufacturing, donation, and surveillance which we have highlighted previously.

6. Strengthen essential health services for COVID and non-COVID patients

Many hospitals across countries that experienced a second wave ran out of oxygen and other essential supplies (e.g. dexamethasone), resulting in preventable deaths and exorbitant out-of-pocket costs for families. When cases are low, countries should strengthen the health systems to make it more resilient to future waves. This involves creating healthcare capacity to manage increased surges in COVID-19 cases, whilst also maintaining essential services, protecting frontline workers with adequate PPE and support, and establishing plans for emergency field hospitals which can be actioned when needed.

Countries should also focus on funding and improving access and supply of oxygen, therapeutics, and essential emergency critical care in all hospitals. In order to relieve the pressure on hospitals in advance, countries should also focus on developing and communicating COVID-19 clinical and home-based care guidelines in collaboration with trusted medical institutions for the use of COVID-19 treatments that are of assured quality, safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness.

In parallel, making plans for sustaining essential health services for non-COVID patients will be of high importance. Since the beginning of the pandemic, concerns about disruptions of services and collateral health impacts have been high in many LMICs. Developing strategies and adaptations in care provision can help health services to cope with the increase in COVID-19 patients and potential avoidance of care from patients. It can also help prioritise and de-prioritise services during a period of crisis using best evidence.

7. Communicate strongly and clearly with the public

Finally, to avert the next wave, it is crucial for governments to communicate a clear and strong message that even if the numbers are low, the pandemic is still not over and the public must remain cautious and prepared to return to distancing measures if numbers begin to rise. This message must be echoed by the highest leadership. Unfortunately, there have been multiple examples of country leaders not heeding warnings, discouraging mask use, downplaying the severity of the pandemic, or claiming that the pandemic was “under control” as cases ballooned.

Individual and collective behaviour has played an important role in both curbing and escalating the crisis in the past year. A well-informed general public, with high health literacy, is essential for suppressing new cases. Strong leadership and regular communication from trustworthy institutions can help sustain the long-term use of masks in public spaces, social distancing (to different levels), testing upon onset of symptoms, and compliance to self-isolation, which will be crucial to help contain any future rise in cases.

Countries must therefore act early to deliver clear and consistent messages that manage the expectations of the public, and provides them with clear guidance on how to behave.

Conclusion

We have learned that even when cases are low, this should not mean a complete return to normality as a transmission can spiral out of control rapidly. Decision-makers cannot afford to be complacent to the risks of subsequent waves; mechanisms for early detection and preparedness will be key to preventing deaths and wider socioeconomic impacts. When cases are low is the time to prepare to avert the next wave.

Disclaimer

Originally published at https://www.cgdev.org