National strategies on Artificial Intelligence A European perspective

2021 EDITION — a JRC-OECD report

AI Watch

Vincent Van Roy (JRC- Digital Economy Unit)

Fiammetta Rossetti (JRC- Digital Economy Unit)

Karine Perset (OECD.AI Policy Observatory)

Laura Galindo-Romero (OECD.AI Policy Observatory)

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming the world in many aspects. It is essential for Europe to consider how to make the most of the opportunities from this transformation and to address its challenges.

In 2018 the European Commission adopted the Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence that was developed together with the Member States to maximise the impact of investments at European Union (EU) and national levels, and to encourage synergies and cooperation across the EU.

One of the key actions towards these aims was an encouragement for the Member States to develop their national AI strategies.The review of national strategies is one of the tasks of AI Watch launched by the European Commission to support the implementation of the Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence.

Building on the 2020 AI Watch review of national strategies, this report presents an updated review of national AI strategies from the EU Member States, Norway and Switzerland.

By June 2021, 20 Member States and Norway had published national AI strategies, while 7 Member States were in the final drafting phase. Since the 2020 release of the AI Watch report, additional Member States — i.e. Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, and Spain — published strategies, while Cyprus, Finland and Germany have revised the initial strategies.

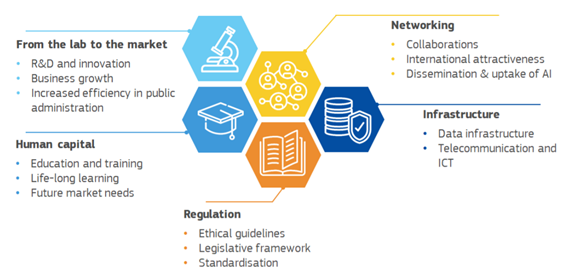

This report provides an overview of national AI policies according to the following policy areas: Human capital, From the lab to the market, Networking, Regulation, and Infrastructure.

These policy areas are consistent with the actions proposed in the Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence and with the policy recommendations to governments contained in the OECD Recommendation on AI.

The report also includes a section on AI policies to address societal challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change. The collection of AI policies is conducted jointly by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) and the OECD’s Science Technology and Innovation Directorate, while the analyses presented in this report are carried out by the JRC, with contributions from the OECD. Both institutions joined forces to ensure that the information supplied by AI Watch and the OECD AI Policy Observatory is harmonised, consistent and up to date. This report is based on the EC-OECD database of national AI policies, validated by Member States’ representatives, and it demonstrates the importance of working closely with relevant stakeholders to share lessons learned, good practices and challenges when shaping AI policies.

Key Messages — AI policy areas

The national policy initiatives are presented in this report according to the following policy areas:

- Human capital: includes all policies to foster the educational development of people in using and developing AI solutions. It includes aspects of formal education and training (e.g. reforms of educational systems towards the inclusion of AI courses and programmes), vocational and continuing learning (e.g. AI training for the workforce), and labour market intelligence and needs (e.g. identifying forthcoming skill needs due to changes in technology developments);

- From the lab to the market: encompasses policy initiatives to encourage research and innovation in AI towards business growth in the private sector and increased efficiency of public services. This area also includes policy instruments to facilitate testing and experimenting with newly developed AI pilots and services;

- Networking: covers all policy initiatives related to AI collaborations across private and/or public sectors and directed to increasing the (inter)national attractiveness of the country (e.g. policies aiming at attracting foreign AI talented individuals and firms to the focal country). This area also includes policies related to the dissemination and uptake of AI such as promotional campaigns and mapping of AI players and applications;

- Regulation: covers policies for the development of ethical guidelines, legislative reforms and (international) standardisation;

- Infrastructure: covers initiatives to encourage data collection, use and sharing, and to foster the digital and telecommunication infrastructure.

These policy areas are consistent with the actions proposed in the Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence and the policy recommendations to governments contained in the OECD AI Principles.

Figure 1 provides an overview of these relevant policy areas for AI and the key objectives to unleash the full potential of AI in Europe.

Figure 1. Overview of relevant policy areas for AI

Source: JRC — European Commission

AI to address societal challenges

In addition to the five abovementioned policy areas, this report includes a specific section on AI policies to address two societal challenges, climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic. The impacts of ongoing climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic are compelling and significantly impact human lives, the environment and economic development. With its recent proposals on the European Green Deal[29] , the EU is leading the way in tackling climate and environmental-related challenges. At the same time, the European Commission is working on all fronts to fight the spread of the coronavirus, to support national health systems and to counter the socio-economic impact of the pandemic.[30]

AI is perceived as a game changer in tackling these societal challenges. In this respect, the 2020 White Paper on Artificial Intelligence[31] highlights that (p 2.) “digital technologies such as AI are a critical enabler for attaining the goals of the Green Deal”. The 2021 review of the Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence proposes forthcoming policy actions to foster the role of AI in support of the European Green Deal and the recovery of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, AI has contributed to countering the current COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 crisis has acted as a boost for AI adoption and data sharing, and created new opportunities for society and the economy.[32] At the European level, AI is also recognised as a key technology to respond to the socio-economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Recovery and Resilience Facility (a temporary recovery instrument to raise funds to help repair the immediate economic and social damage and centrepiece to Europe’s recovery plan NextGenerationEU, in which 20% of the funding is earmarked for digital including AI) highlights the importance of green and digital transitions for recovery.[33]

4 Insights from national AI strategies and policies in the EU

This section provides insights from national AI strategies across EU Member States, and Associated Countries (Norway and Switzerland). It highlights a range of policy approaches across diverse policy areas and provides examples of good policy practices. National strategies differ in both the scope and approaches to the regulation of AI, ranging from high-level strategies with different policy initiatives to concrete action plans with specific milestones and time frames (e.g. Bulgaria, Estonia and Hungary). AI policies can also be incorporated in a wider strategy of digital transformation, as for Slovakia. Recently published or updated strategies (e.g. Germany and Spain) include policy initiatives in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and sustainability issues, such as environmental and climate change.

More detailed information on AI policies for each specific country can be found in Section 5 of the report and is available on the EC-OECD database of national AI policies, the AI Watch Portal and the OECD.AI Policy Observatory.

4.1 Human capital

As part of the national AI strategies, governments are supporting human capacity building in AI and aim to prepare for the labour market transformations brought about by AI technologies. The objective is to provide current and future generations with the necessary skills and competencies in AI and to anticipate labour market trends. To this purpose, several EU Member States have developed AI skills strategies to address the challenges posed by the increasing digital transformation of the world of education and work. For example, as outlined in Malta’s AI strategy, the Malta College of Arts, Science & Technology has released an AI Strategy and Action Plan 2020–2025 in which it outlines policy actions towards the introduction of AI in higher education (see Section 5.19.1). Similarly, the Swiss Government published a strategy on Artificial Intelligence in Education highlighting the opportunities and challenges of AI for the education system (see Section 5.27.1).

Most countries commonly follow a similar policy approach to nurture AI talents. First, national strategies aim to strengthen the provision of AI competencies at all education levels with supportive policies for education reforms. Education reforms in the primary and secondary education systems typically include courses on ICT, digital literacy and AI, often complemented with courses on judgement and problem solving, creative and critical thinking, and interpersonal communication. AI competencies at tertiary education levels are fostered through increased support for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects, and the creation of Bachelors, Masters, PhD and postgraduate programmes in AI-related fields.[34] To guarantee high-quality levels of education in AI, most countries also develop policies to enhance teachers’ competencies in teaching and working with digital and AI technologies.

Second, national strategies also propose actions to promote a culture of lifelong learning and continuous up/reskilling of citizens. This is typically done through massive open online courses (MOOCs) and on-the-job trainings in AI for employees in the public and private sector. An example is the Finnish MOOC Elements of AI (see Section 5.9.1)[35], which aims to demystify AI with a basic and more advanced course on AI. While Finland initially aimed to train 1% of its population, the course attracted more than 100,000 participants, representing more than 2% of the population. To reach as many people as possible, the online course is being translated into all languages of the European Union.

Finally, governments are setting up policies to evaluate the future needs of the labour market in terms of digital and AI competences. The Czech Republic, for example, will monitor the labour market and anticipate future labour requirements to improve career guidance, worker mobility and reskilling opportunities (see Section 5.6.1). Similarly, Sweden developed a pilot project to identify the skills needed for better use of emerging technologies such as AI (see Section 5.28.1). Germany is monitoring the impact of AI on the labour market for policy intervention through the Observatory for Artificial Intelligence in Work and Society (or AI Observatory)[36], and also supports the OECD Programme on AI in Work, Innovation, Productivity and Skills (AI-WIPS). AI-WIPS analyses the impact of AI on the labour market, skills and social policy while providing opportunities for international dialogue and policy assessments.[37]

4.2 From the lab to the market

Bringing AI developments from the lab to the market can only be successful in a well-supported enterprise-driven ecosystem with sufficient scope and funding for AI research and innovation activities[38], including incentives for experimentation. Funding and support programmes should target the development of initial ideas to pave the path towards promising emerging fields in AI. In addition, it is critical to support the transformation of AI concepts into successful products and services, with policy instruments all along the innovation process from the lab to the market.[39] It equally requires support mechanisms for the uptake and use of AI in public administration.

Against this background, countries have taken various measures to stimulate and support AI research. A large majority of the EU Member States, Norway and Switzerland have developed or are in the process of creating national competence centres in AI research.

Examples of national competence centres include the Finnish Centre for Artificial Intelligence (FCAI), the French interdisciplinary institutes of Artificial Intelligence (3IA), the Danish National Centre for Research in Digital Technologies (DIREC), the six German Competence Centres for AI Research and the Hungarian Artificial Intelligence National Laboratory (MILAB). Some research centres have a more general approach and target many research fields in AI, others are more specific. The Hungarian National Laboratory for Autonomous Systems is for instance focused on autonomous systems, while the Polish Centre for CyberSecAI[40] and the forthcoming competence centre in Slovakia[41] are specialised in cyber security procedures for AI systems. Lastly, Estonia has a Competence Centre Specialised in Machine Learning and Data Science (STACC).

Cross-border co-operation in AI research is also a priority for EU countries. Figure 2 illustrates AI international research collaboration.

Figure 2. International collaboration on AI research

Source: OECD.AI (2021), visualisations powered by JSI using data from MAG, version of 15/03/2021, accessed on 17/5/2021, www.oecd.ai

Note: the thickness of a connection represents the number of joint AI publications between two countries for the selected time period. Data downloads provide a snapshot in time. Caution is advised when comparing different versions of the data, as the AI-related concepts identified by the machine learning algorithm may evolve in time. Please see the methodological note for more information.

To increase innovation in AI and foster the creation and growth of AI businesses, many countries are complementing existing and general funding instruments for innovation with more AI-focused funding schemes and support programmes. Commonly reported funding instruments that have been in place for many years are innovation vouchers, seed capital, venture capital schemes (particularly targeting SMEs), and business growth programmes. Malta, for example, has reformed its Seed Investments Scheme with more favourable tax credit conditions for innovative AI firms.

Several countries have developed or are developing AI readiness tools to evaluate the digital and AI maturity of businesses and to identify government guidance and policy actions for innovation support. The Finnish AI maturity tool helps organisations to increase their business opportunities in identifying their most important areas for improvement in AI (see Section 5.9.2). Other policies such as the Danish Sprint:Digital offer support for the digital transformation of Danish SMEs and the development of new digital business models (see Section 5.7.2).

To support AI start-ups during their first business years, Belgium, Malta and Sweden have developed dedicated support programmes on AI for young companies. Through the Belgian Start AI programme and Tremplin AI programme (see Section 5.2.2), the Swedish Startup AI activities funding (see Section 5.28.2) and the Maltese YouStartIT accelerator (see Section 5.19.2), start-ups are supported in their discovery of AI at early stages of the innovation process (e.g. during the proof of concept (PoC) phase). In a similar vein, though not necessarily targeting only start-ups, Finland launched the Artificial Intelligence Accelerator to facilitate companies in bringing AI experiments into production (see Section 5.9.2). Cyprus and Hungary are planning to set up similar AI accelerator programmes/centres in the near future.

Most countries highlight various priority sectors in their national AI strategies with a high potential for AI applications. The most commonly reported sectors are manufacturing, agriculture, healthcare, transport and energy. In addition to these priority sectors, a number of countries prioritised language technologies in their AI strategies as key to enabling interactive dialogue systems and personal virtual assistants for personalised public services. For example, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Slovakia, and Spain report supportive policies for natural language processing. Slovakia is developing a tool for natural language processing to accelerate the development of AI in the private sector and improve the quality of public services. Spain launched a project on the Spanish Language and AI (LEIA) to promote and enable the use of the Spanish language in the digital world. These policy efforts continue the action lines outlined in the National Plan for Advancement in Natural Language Processing (see Section 5.27.5). Denmark is focusing on language technologies to support ‘AI in Danish’ and in June 2020, launched a platform displaying metadata of existing linguistic resources to facilitate the development of language technologies in Danish (see Section 5.7.5).

Lastly, governments are also setting up policies to spur AI innovation and use in public administration.[42] Such policies include AI programmes for public services, e-governance strategies to improve the digitalisation process of public administration, support for innovative public procurement and sharing good practices. Initiatives such as GovTech Polska and GovTech Lab Lithuania are good examples of how to boost the innovation ecosystem in the public administration and AI.

4.3 Networking

Networks and collaborative platforms are important for a swift deployment of AI. Bringing the relevant community together and combining expertise and efforts from various sources can help to seize (the often ambitious) AI opportunities.[43]

Against this background, many governments have set up policies to build innovation communities by bringing together tech companies, research centres, innovation actors and citizens. Examples are the Belgian Beacon initiative, the Czech Knowledge Transfer Partnerships programme, the Finnish AuroraAI national programme, the German the Plattform Lernende Systeme, the Norwegian AI Research Consortium, the Polish Virtual Research Institute, the Portuguese collaborative laboratories, and the Slovak.AI platform.

To further increase innovation community building, the governments of Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Finland, Poland and Spain have developed maps of AI actors and applications. These maps provide an overview of academic institutions, research centres, public administrations and companies active in AI. They also monitor ongoing technological and scientific activities in AI and encourage networking opportunities.

In addition, EU Member States, Norway and Switzerland support the establishment and further expansion of digital innovation hubs (DIHs). DIHs are important channels for networking opportunities to foster the digital and AI transformations of industries. Well-established DIHs in AI-related fields are the CYRIC Digital Innovation Hub of Cyprus (expertise in IoT and robotics), the Ventspils High Technology Park of Latvia (expertise in robotics and automation), and the Luxembourg Digital Innovation Hub (expertise in AI and digital infrastructure, such as HPC and data centres).

Global and Pan-European networks are further developed through initiatives such as the OECD.AI Network of Experts. The network is a multi-stakeholder and multi-disciplinary group that provides AI-specific policy advice to the OECD and contributes to the OECD.AI Policy Observatory. It is composed of over 200 experts, including AI policy experts, technical experts and experts from social sciences and humanities. The network consists of a working group on classifying AI systems; a working group on implementation tools for trustworthy AI; a working group on national AI policies and a task force on AI compute.

The EC and some EU Member States also participate in the Global Partnership on AI (GPAI). The GPAI brings together experts from industry, civil society, governments and academia. It supports cutting-edge research and applied activities on AI-related priorities. In May 2021, the European Commission and the following EU Member States were involved in the Global Partnership in AI: France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, and Spain.

Many countries are also setting up policies to attract AI talent and investments from abroad. To this purpose, some countries have dedicated strategies, such as the researchers’ mobility programme in Cyprus and the forthcoming Spanish Talent Hub programme. Other policies aim to improve working conditions for foreign talents by facilitating administrative procedures. This is achieved by simplifying and accelerating procedures to acquire a residence and a working permit for foreign researchers and their family members. The Czech Republic, Finland, Italy, Malta, Portugal and Spain are implementing this through start-up visas and fast-track services for valuable talents coming from abroad.

Lastly, the majority of countries is also exploiting social media channels and organising public events to raise awareness on AI and to increase networking opportunities. The Maltese strategy announces for instance a public investment of EUR 1 million per year for promotion campaigns and outreach activities. Slovenia plans to launch a communication platform for the collection and dissemination of good practices and case studies on the use and deployment of AI in society. Similarly, Hungary will organise an annual innovation award for AI application projects to make AI developments visible to the broader public.

4.4 Regulation

The use of certain AI technologies raises ethical and legal issues, necessitating the development of a legal framework for human-centric and trustworthy AI.[44] These issues relate to human rights, privacy, fairness, algorithmic bias, transparency and explainability, safety and accountability, among others.

National actions to address ethical concerns differ across countries in terms of strategic approach and level of focus. Finland released the government report on Ethical information policy in an age of artificial intelligence outlining principles for fair data governance, including guidelines for the use of information and ethical values. Denmark proposes a specific focus on the responsible and sustainable use of data by the public and private sector. In December 2019, a Data Ethics Toolbox was launched to support companies to adopt and implement data ethics into their business models. In January 2021 a Danish law entered into force on data ethics compliance for Denmark’s largest companies. It is accompanied by a guide for business on how to include data ethics in their annual reports. Sweden established an AI sustainability centre, which acts as a hub co-founded by companies, universities and public authorities with a specific focus on the social and ethical aspects of AI.

To facilitate the development of ethical guidelines many governments have established AI ethics committees and councils. These bodies provide recommendations on ethical issues and continuously monitor the use and development of AI technologies. They also raise ethical awareness through the provision of good practices, training and ethical codes of conduct for researchers and practitioners in both the public and private sector.

Many governments also implement monitoring and reward systems for compliance with principles for trustworthy AI. Malta has developed an AI certification framework, issued by the Malta Digital Innovation Authority (MDIA). It serves as valuable recognition in the marketplace that the AI systems of successful applicants have been developed in an ethical, transparent and socially responsible manner (see Section 5.19.4). Similar quality seals or labels — acting as hallmarks for a responsible approach in AI — have been adopted in other countries such as Denmark and Germany. The Czech Republic, Italy, Lithuania, and Spain are considering developing them as well. Similarly, the AI registers set up by the cities of Amsterdam and Helsinki (see Section 5.9.4) aim to ensure a secure, responsible and transparent use of AI algorithms.

Various EU Member States are setting up AI Observatories and knowledge centres to support and enable socially responsible and ethically sound implementations of AI. An example of such an initiative is the planned Artificial Intelligence Regulation and Ethics Knowledge Centre of Hungary. This centre aims is to create and coordinate an extensive pool of experts to advise on legal issues and ethics of AI.

In terms of legislation, many governments highlight the need to evaluate the current legal framework and to adopt new EU level legislation to guarantee a binding regulatory framework for the successful uptake and deployment of AI. Countries are starting to develop sector-specific regulations for well-defined fields of AI that are currently not or not sufficiently covered by existing EU legislation. A notable example in this respect is the regulation on automated driving. Many governments (e.g. Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic Germany, Lithuania and Spain) have adopted regulations to allow for the testing of automated vehicles and associated technologies on public roads. Other regulatory fields that receive particular attention are (health care) data and automated decision making. Norway is for instance working on proposals for amending its Health Register Act to delineate the use of data for patient treatments and rules of consent from individuals (see Section 5.21.4). Slovakia is also preparing a new Act on Data to better define regulations on data protection, disclosure principles, data access and open data regulations. Regarding the latter field, the Dutch Government has implemented the Law Enforcement Directive in its national legislation, which contains provisions on automated decision making for law enforcement. Finland and Portugal are also developing national regulations for automated decision-making to determine liability issues among others.

Many governments are also considering the establishment of controlled environments for AI experimentation, for example by developing regulatory sandboxes.[45] The objective of the sandboxes is to facilitate experimentation in real-life conditions while temporarily reducing regulatory burdens to help testing innovations.[46] Although announced in several national AI strategies of EU Member States, Norway and Switzerland, the development of regulatory sandboxes for AI is still at an embryonic stage in most countries. Germany’s AI strategy plans the establishment of AI regulatory sandboxes and testbeds, such as the “Digital Motorway testbed A9” (administrated by the Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure). These make it possible to test technologies in a real-life setting and to screen the regulatory environment and make adjustments (see Section 5.11.2). Similarly, The Italian Government put in place regulatory sandboxes through the Sperimentazione Italia initiative to facilitate controlled experiments with innovative products, including AI.

4.5 Infrastructure

As AI algorithms often involve large amounts of data, it is crucial to establish a solid data environment to collect, share and analyse big data.[47] To this purpose, governments are supporting the development of data infrastructures to ensure the provision of reliable and high-quality data that can be shared with a wide range of users in a robust and accessible way. Several EU Member States have developed specific national data strategies to set the foundations for trustworthy data use and exchanges. Commonly, these strategies outline policy actions for open data governance, the creation of data repositories and data management such as the improvement of data interoperability across databases and the protection of individual and collective rights. The Data Strategy of the German Federal Government for instance identifies four concrete fields of actions: the improvement of data provision and access, the promotion of responsible data use, the increase of data competencies in society and the development of a data culture for data sharing and use. Similarly, the Czech Republic launched a National Strategy on Open Access to Research Information for the years 2017–2020 to initiate a gradual process to open access to scientific information at the national level. Other countries, such as Spain, integrate their policies towards a data economy into the broader umbrella of the Digital Agenda 2025 strategy.

To create an open data culture, countries are setting up open data and open science policies. In this respect, the Portuguese Open Data Policy and the Danish Open Science Policy are good examples of how to provide guidelines for managing and sharing data in the scientific community, while ensuring data integrity and open access.

Open data platforms and portals have been developed in all EU Member States, Norway and Switzerland. They commonly aim to provide free access to data of the public administration and to encourage its secondary use. In addition to non-commercial data, some governments are planning to support commercial data platforms. Hungary for instance foresees to support the creation of a data market place to encourage the transmission of non-personal data of high quality for commercial purposes.

Finally, several EU Member States and Norway have set up governance bodies and data chief officers to support and encourage data utilisation. These public bodies act as facilitators to coordinate and stimulate the management of national data assets and to foster open data governance.

A wide range of policies is also taken by governments to foster the quality and capacity of the telecommunication and ICT infrastructure, crucially needed to enhance data analytics resources for AI. All Member States and Associated countries mention supporting the access to secure data storage, highperformance computing, affordable high-speed broadband networks and next-generation software for data analytics. Participation in the European High-Performance Computing Joint Undertaking (EuroHPC) is often highlighted in national AI strategies. EuroHPC announced eight sites to host world-class supercomputers. They are located in Sofia (Bulgaria), Ostrava (Czech Republic), Kajaani (Finland), Bologna (Italy), Bissen (Luxembourg), Minho (Portugal), Maribor (Slovenia), and Barcelona (Spain). Some countries have also released dedicated strategies for the creation of high-performance computing. The Advanced Computing Portugal 2030 strategy outlines action lines to transform Portugal into an advanced computing service economy by 2030 (see Section 5.23.5). In addition, governments are increasing computing capacities through investments in cloud services and quantum computing. In this respect, the Malta Hybrid Cloud initiative procured by MITA is an example of how to enable access to cloud platforms for the public and private sector (see Section 5.19.5). Finally, governments mention their support for high-quality connectivity and nationwide 5G deployment.

4.6 AI to address societal challenges

Climate and environment

To tackle the ongoing climate change and environmental challenges, Member States and Associated Countries are embracing AI solutions and support the development of innovative ideas from the lab to the market. As highlighted in the Coordinated Plan on AI 2021 review[48], AI technologies could primarily support the achievement of the Green Deal objectives through four main channels: 1) transition to a circular economy, 2) better setup, integration and management of the energy systems, 3) more efficient transport, and decarbonisation of buildings, agriculture and manufacturing, and 4) enabling new solutions that were not possible with other technologies.

Many governments are setting up ambitious R&D programmes and calls for proposals to support the development of AI solutions for the achievement of the Green Deal objectives. Prominent examples are the German Lighthouses of AI for Environment, Climate, Nature and Resources (see Section 5.11.6), the Lithuanian call for proposals on Green industry innovation (see Section 5.17.6) and the Swedish R&D call on AI in the service of climate (see Section 5.28.6). These programmes commonly target applied research projects, not only in the fields of energy efficiency and reduced greenhouse gas emissions but also e.g. for the protection of biodiversity, water management and sustainable consumption.

At the same time, the education offer with a combined focus on AI and environmental issues remains rather limited. Most Member States are expanding their education offer at all levels, including formal and informal education programmes for advanced digital skills in fields such as AI and high-performance computing. However, little attention seems to be given so far to the development of education programmes that teach how AI can be used to address critical and global environmental challenges.[49]

The creation of AI technologies for a greener and more sustainable economy and society is further supported through the development of cutting-edge data ecosystems and high-end ICT infrastructure. Countries, such as France and Switzerland, have for instance developed strategies on energy and data.[50] These strategies outline recommendations and policy actions to mitigate climate change and to support digital and AI-related innovations for energy efficiency based on improved data infrastructures. Other countries, such as the Netherlands and Latvia support the use of AI to exploit the vast and often untapped environmental data sets in their public administrations. To this purpose, the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) provides access to its databases and has created the KNMI DataLab to facilitate and coordinate innovations in the fields of climate change, weather forecasting and seismology (see Section 5.20.6). Similarly, Latvia provides access to the data repositories from the Latvian Environmental, Geological and Meteorological Centre (VSIA) containing meteorological radar images, measurements, and forecasting data. In addition, high-performance computing centres run the data-driven and computationally-intensive environmental models. Ireland has various projects at the Irish Centre for High-End Computing (ICHEC). First, in collaboration with other institutes, this centre has established various national platforms to ensure the provision of high-quality data (on satellite images and oceanographic data, among others) and to enhance possibilities for data exchange. Second, the complex compute solutions and infrastructures of the centre are used in many collaborative projects with public institutions both at the national and European level.[51] Moreover, other high-performance computing centres, such as the Vienna Scientific Cluster 4 (VSC-4) and the Bulgarian Strategic Centre for Artificial Intelligence (SCIA) leverage their facilities to forecast the impact of climate change using big data and machine learning techniques.

COVID-19 pandemic

To quickly respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, governments actively support the development of AI-powered technologies with targeted R&D programmes and investment funds. Member States and Associated countries are supporting dedicated research projects within hospitals, research centres, and universities. For example, the Danish Government has allocated a total of EUR 20 million for research and development to combat the pandemic and has launched various signature projects on AI and health.[52] Similarly, Ireland established the Rapid Response Research and Innovation programme in March 2020 to enable the research and innovation community to respond to the challenges raised by the pandemic. Other examples include the R&D projects at the Finnish Centre for Artificial Intelligence, the AI-enabled methods to model the COVID-19 replication process at the French HPI research laboratory, the innovative AI-powered tools to track and model the spread of the virus at the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment and the COVID19 Activities at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute.

To increase the speed of scientific breakthroughs for developing COVID-19 solutions, many governments are encouraging national and international collaborations among relevant stakeholders, including the public sector, private sector, and civil society. This is commonly done by fostering collaborative partnerships and organising hackathons, which help to collect innovative ideas about deployable AI and robotics solutions to face the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. Notable examples of initiatives supporting collaborative partnerships are the EU Framework programmes (e.g. Horizon2020) and the Global Partnership on AI (GPAI).

With respect to Horizon2020, in August 2020, the Commission announced to support 23 new collaborative research projects with EUR 128 million in response to the continuing coronavirus pandemic.[53] Also, the GPAI is supporting the responsible development and use of AI-enabled solutions to COVID-19 and other future pandemics. To this end, a working group on AI and pandemic response has been formed to promote crosssectoral and cross-border collaboration in this area. Multiple hackathon events have been organised in Europe. Among them, the #EuvsVirus hackathon promoted cross-European partnerships to come up with innovative solutions to fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.[54] Many countries, such as the Czech Republic, Greece, Latvia and Lithuania have also organised hackathons at a national level.

The global challenges stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic have urged governments to provide access and promote sharing of research data. In April 2020, the European Commission and several stakeholders established a COVID-19 data portal to enable rapid and open sharing of research data. Similarly, the Swedish COVID-19 Data Portal provides information, guidelines, tools and services, to support researchers to use Swedish and European infrastructures for data sharing.

Various AI-enabled technologies such as virtual assistants and chatbots have been launched to help governments and healthcare organisations provide people with reliable information about COVID-19. Examples of these AI solutions include the Czech Republic’s chatbot, Estonia’s chatbot Suve, Lithuania’s AIpowered virtual assistant ViLTė and France’s virtual phone assistant AlloCOVID. All these AI-powered solutions have the objective to provide accurate and trustworthy information about the emerging situation related to COVID-19.

Finally, countries offered their support in the field of high-performance computing (HPC) to help to find treatments for the novel coronavirus. In this respect, the EU-funded Exscalate4CoV (E4C) project is a good example of how European supercomputers can be used to find new therapies for COVID-19. This project consists of a coalition between public and private partners located across seven European countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland). Participating pharmaceutical firms, research institutions, and biological laboratories exploit the computing power of three HPC centres in Bologna, Italy; Barcelona, Spain; and Jülich, Germany.

References

See the full version of the report