The Health Institute

research and strategy institute for

in-person health strategy and

digital health strategy

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Chief Research and Editor —

for The Health Institute — Knowledge Portal Unit

Chief Strategy Officer (CSO) —

for The Health Institute — Research and Strategy Unit

Senior Advisor — for Boards and C-Level

July 6, 2023

ONE PAGE SUMMARY

A new study published in BMJ Global Health shows that countries with strong pandemic preparedness had lower COVID-19 mortality rates compared to less prepared nations.

- The study analyzed the pandemic performance of countries by adjusting for age-related demographics and the capacity to diagnose COVID-19 cases and deaths.

- Countries with higher scores on the Global Health Security Index (GHS Index), which measures pandemic preparedness, had lower excess COVID-19 mortality rates.

Pre-pandemic investments in capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to disease threats saved lives during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The study highlights the importance of preparing for pandemics before they occur to protect the health of populations and achieve better outcomes.

The United States, despite ranking highest on the GHS Index, had higher comparative mortality ratios than 62 other countries, indicating that the utilization of preparedness tools and resources impacts overall performance.

The United States’ performance was affected by deficiencies in its risk environment, including

- a disorganized COVID-19 response,

- inconsistent messaging, and

- delays in testing equipment distribution.

- Countries with higher scores in the risk environment category, such as Iceland, Australia, and New Zealand, had lower mortality rates during the pandemic.

The study emphasizes the need for complete and properly analyzed information to drive efficient and effective pandemic response, especially in low-income countries.

- Improving pandemic preparedness is crucial to mitigate the impact of future infectious disease threats.

Infographic

DEEP DIVE

New Study Shows Robust Pandemic Preparedness Strongly Linked to Lower COVID-19 Mortality Rates

Preparedness matters: Accounting for age and national capabilities to diagnose COVID-19 deaths reveals that pre-pandemic investments in capacity saved lives — though U.S. remains an outlier.

The vast majority of countries that entered the COVID-19 pandemic with strong capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to disease threats achieved lower pandemic mortality rates than less prepared nations, according to a major new study published today in BMJ Global Health. The analysis was led by researchers from the Brown University School of Public Health, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI).

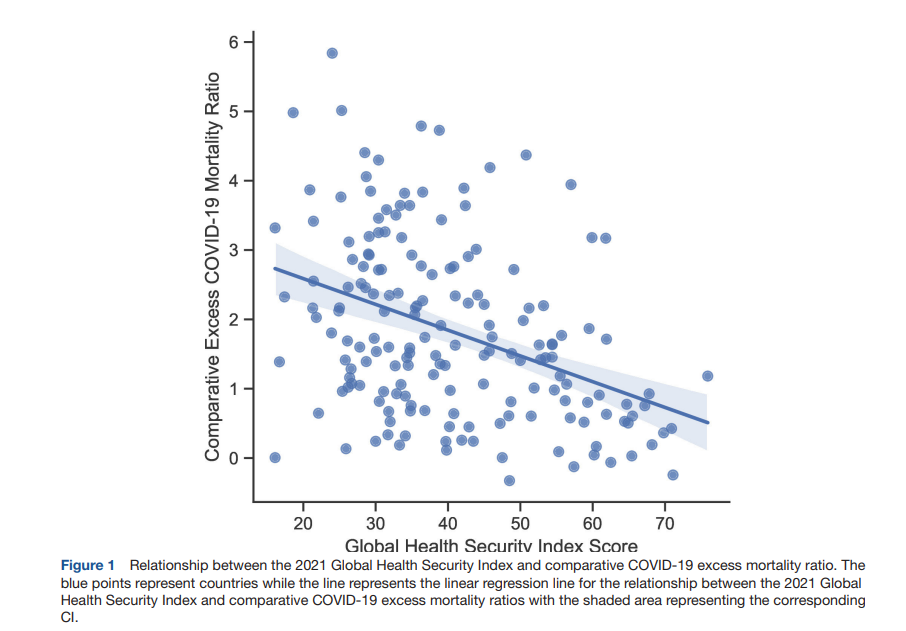

The study found that when accounting for two key differences between countries — the age of their populations and their capacity to diagnose COVID-19 cases and deaths — the pandemic clearly was less deadly in countries that rank high on the Global Health Security Index, which measures the pandemic preparedness capacities of 195 countries.

The researchers sought to understand how different countries performed during the COVID-19 pandemic and how that relates to their pandemic preparedness capacity as measured by the GHS Index.

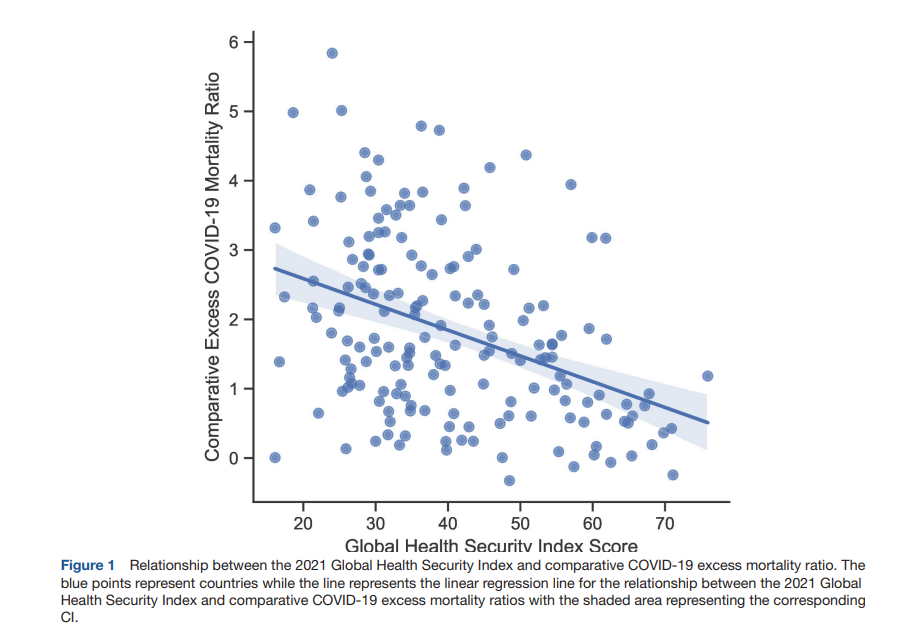

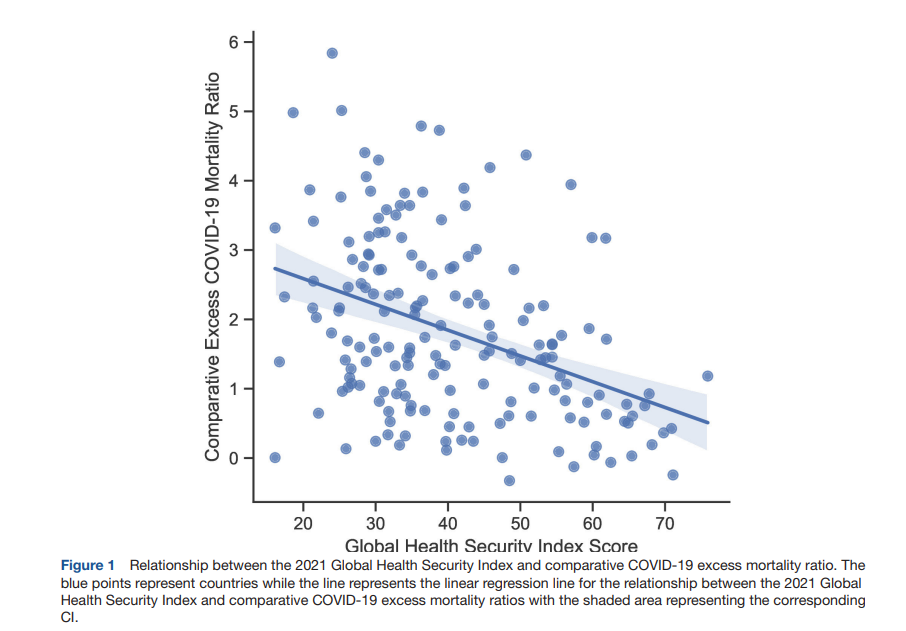

To answer this question, they assessed countries’ pandemic performance by examining “comparative mortality ratios,” which involved adjusting countries’ “excess deaths” to account for differences in the age of each country’s population. Excess deaths are calculated by comparing the number of deaths that occurred during the pandemic to pre-pandemic death trends. When the researchers took this approach, they found a significant correlation between higher levels of pandemic preparedness capacity and lower excess COVID-19 mortality. Overall, these findings correct earlier observations that countries that scored high on preparedness, including in the GHS Index, paradoxically experienced the worst overall COVID outcomes and the highest COVID-19 death rates.

“

Our analysis confirms what you would expect, which is that preparing for pandemics before they occur means we can save more lives during a global health emergency,” said Dr. Jennifer Nuzzo, Director of the Pandemic Center at the Brown University School of Public Health and the senior author of the study. “Countries that took significant action before the pandemic to invest in capacity to prevent, detect and respond to these types of events were much more effective at protecting the health of their populations and had much better outcomes overall.”

The study is the first comprehensive analysis of the “comparative mortality ratio” that accounts for a key factor that can distort national death rates: the age-related demographics of the population. Accounting for age is important when measuring pandemic response performance because countries with older populations tend to have higher baseline mortality rates. The use of the “comparative mortality ratio” also accounts for the fact that some countries with weak disease detection and reporting systems tend to under-report COVID cases and deaths — which can distort the data and make it look like better prepared countries did worse than those with fewer capacities. The authors note that the failure to account for age and reporting capabilities has led some to the erroneous conclusion that strong pandemic preparedness capacity has had little impact on COVID outcomes.

“

It is crucial to get the details right when analyzing the relationship between pandemic preparedness capacity and outcomes,” said Dr. Jaime M. Yassif, Vice President of Global Biological Policy and Programs at NTI. “As countries evaluate their COVID-19 performance, we can now point to clear evidence of the immense value of building essential pandemic preparedness capacity and the deadly consequences of failing to do so.”

Although most highly prepared countries appear to have used their capacities well, the United States emerged as a key outlier. Despite ranking highest in the Index, 62 countries had lower comparative mortality ratios than the United States, illustrating that the way a country uses the tools and resources at its disposal also impact its overall performance.

The study highlights one factor that could help explain the United States’ performance. It entered the pandemic with relatively poor scores in what the GHS Index calls the “risk environment,” which includes measures of a country’s capacity to develop and implement policies that can affect its ability to marshal a timely, effective response. The study explains that in the United States, these deficiencies were manifest in a disorganized COVID-19 response that was likely hampered by different control measures in different states, rules that slowed down the distribution of testing equipment, and inconsistent messaging that may have undermined compliance with pandemic control measures like social distancing and vaccination.

Separately, the study found that top performers in the GHS Index risk environment category — including Iceland, Australia and New Zealand — also posted some of the lowest mortality rates during the pandemic.

“

This study offers compelling evidence that lack of preparedness tragically led to greater loss of life during the COVID-19 pandemic, and these vulnerabilities will continue to hold populations at risk when new infectious disease threats inevitably emerge in the future,” said Dr. Oyewale Tomori, a virologist and former president of the Nigerian Academy of Science who is closely involved in a number of global initiatives to improve pandemic response. “This evidence, borne from the GHS Index, highlights the importance of getting every country — especially low-income ones — to have complete, properly analyzed information to drive efficient and effective pandemic response. This underscores the value of ongoing GHS Index assessments.”

Originally published at https://www.nti.org

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

Evaluation of the Global Health Security Index as a predictor of COVID-19 excess mortality standardised for under-reporting and age structure

bmj

Jorge Ricardo Ledesma1, Christopher R Isaac2, Scott F Dowell3, David L Blazes3, Gabrielle V Essix2, Katherine Budeski4, Jessica Bell2, Jennifer B Nuzzo1,5

Abstract

Background

- Previous studies have observed that countries with the strongest levels of pandemic preparedness capacities experience the greatest levels of COVID-19 burden.

- However, these analyses have been limited by cross-country differentials in surveillance system quality and demographics.

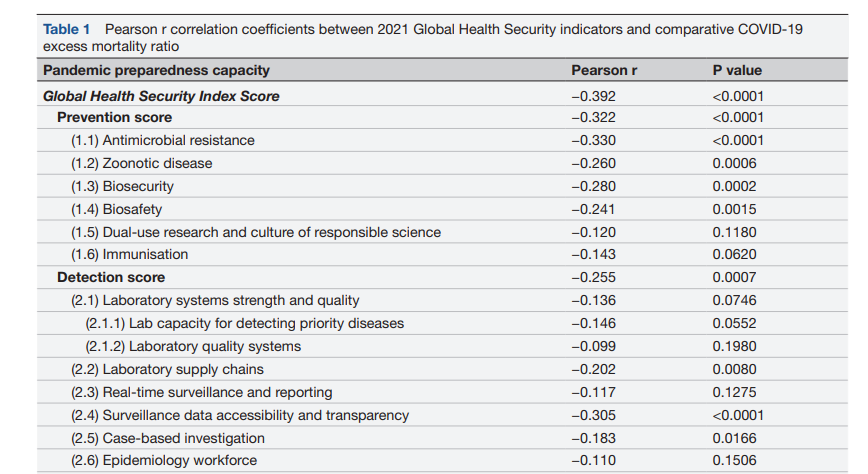

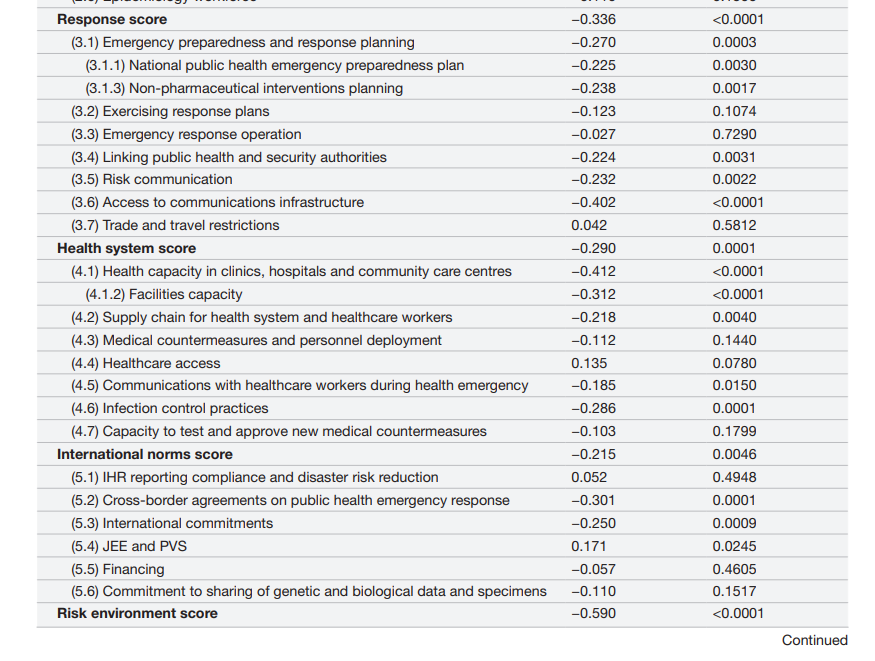

- Here, we address limitations of previous comparisons by exploring country-level relationships between pandemic preparedness measures and comparative mortality ratios (CMRs), a form of indirect age standardisation, of excess COVID-19 mortality.

Methods

- We indirectly age standardised excess COVID-19 mortality, from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation modelling database, by comparing observed total excess mortality to an expected age-specific COVID-19 mortality rate from a reference country to derive CMRs.

- We then linked CMRs with data on country-level measures of pandemic preparedness from the Global Health Security (GHS) Index.

- These data were used as input into multivariable linear regression analyses that included income as a covariate and adjusted for multiple comparisons.

- We conducted a sensitivity analysis using excess mortality estimates from WHO and The Economist.

Results

- The GHS Index was negatively associated with excess COVID-19 CMRs (table 2; β= −0.21, 95% CI= −0.35 to −0.08).

- Greater capacities related to prevention (β= −0.11, 95% CI= −0.22 to −0.00), detection (β= −0.09, 95% CI= −0.19 to −0.00), response (β = −0.19, 95% CI= −0.36 to −0.01), international commitments (β= −0.17, 95% CI= −0.33 to −0.01) and risk environments (β= −0.30, 95% CI= −0.46 to −0.15) were each associated with lower CMRs.

- Results were not replicated using excess mortality models that rely more heavily on reported COVID-19 deaths (eg, WHO and The Economist).

Conclusion

- The first direct comparison of COVID-19 excess mortality rates across countries accounting for under-reporting and age structure confirms that greater levels of preparedness were associated with lower excess COVID-19 mortality.

- Additional research is needed to confirm these relationships as more robust national-level data on COVID-19 impact become available.

Discussion

There are multiple factors that create a challenging environment for fully understanding the impact of COVID-19 relative to existing external assessments.

Some factors include consistent generation of high-quality data, availability of and competition for scarce resources such as PPE and vaccines, and imperfect understandings of variation between and within populations. For example, the availability of comparable data is a persistent challenge with international comparisons of COVID-19 outcomes. Detailed age-specific mortality rates are currently only available for 22 countries. COVID-19 case counts are further affected by variable country-specific testing capacity, inclusion criteria and reporting. Data on COVID-19 deaths are similarly limited and under-reported due to differences in vital statistics performance across the world. Additionally, the effect of intense competition for vaccines clearly suggests a strong influence of national wealth on COVID-19 outcomes. However, higher-income countries also tend to have older populations. Thus, examinations of excess mortality that are adjusted for age provides urgent information for assessing the role health security capacities have in mitigating COVID-19 burden.

This analysis therefore represents the first direct comparison of COVID-19 excess mortality rates across countries that accounts for under-reporting and national age structure.

We found that after adjustment for income, higher GHS Index scores were associated with lower CMRs for excess COVID-19 mortality.

The adjusted analysis confirms the expected relationship to preparedness illustrating that efforts to prepare for and respond to pandemics before they occur are effective in reducing mortality during global health emergencies.

Having existing capacities and infrastructures in place therefore provides urgent resources that countries can use to mitigate the impact of infectious disease threats.

Our findings underscore that the core pandemic preparedness capacities of infectious disease prevention, detection and response are each associated with lower excess COVID-19 deaths.

For example, prevention capacities may have reduced excess COVID-19 deaths by impeding the emergence of other infectious disease outbreaks35 36 that may have further burdened health systems and contributed to more mortality during the pandemic.

In this context, our finding that the prevention indicator of immunisation capacities and rates being associated with fewer excess deaths is expected as this capacity likely minimised the number of vaccine preventable deaths37–39 and provided an infrastructure for successful COVID-19 vaccination programmes.40 41

We further observed that detection capacities, specifically capacities related to laboratory systems for detection of priority diseases and case-based investigations, were associated with less excess COVID-19 deaths.

These findings are aligned with previous work illustrating that these capacities allow for early identification of cases,42 43 which increase the likelihood of early access to treatment, isolation of cases to minimise disease transmission and supports the effectiveness of mitigation strategies.44–46

These early detection capacities therefore contribute to improved health outcomes and fewer excess deaths.14

In addition, the finding that case-based investigation capacities were associated with reductions in excess deaths is consistent with previous work illustrating that these strategies reduced COVID-19 transmission47 48 and case fatality rates.49

Our findings also confirm that capacities for rapid responses to mitigate disease spread are associated with reduced COVID-19 burden.50–52

In particular, our results indicate that having a framework for emergency preparedness and response, which includes having health emergency plans, non-pharmacological intervention plans and considerations of vulnerable populations, is associated with fewer excess COVID-19 deaths.

We may have observed this relationship owing to previous investigations finding that a lack of health emergency plans may lead to ineffective implementation of mitigation strategies.53–55

Therefore, having a framework for emergency response equips countries with existing strategies that they can draw on during emergencies.

Another response capacity that was related to reduced excess deaths was access to communication infrastructure.

A myriad of studies has indicated that communication of disease risks increases knowledge of the disease56–58 and adherence to interventions,59 60 with some studies suggesting that risk communication is one of the most effective COVID-19 mitigation strategies.61 62

We may have found a strong relationship for communication infrastructure, as this capacity may have been essential for implementation of risk communication strategies in populations.

However, we did not observe an association between the health system category, a metric of health systems’ abilities to successfully treat patients, and excess deaths after adjustment for multiple hypotheses.

Though we did not find an association, there is still evidence that greater health system capacities are associated with fewer excess deaths as our results trended in that direction, and our sensitivity analysis where we adjust for COVID-19 mitigation strategies demonstrated the expected relationship.

Further, there are numerous studies confirming that greater health system capacities are indeed associated with less COVID-19 burden by improving treatment outcomes,63–65 and that stronger health systems can minimise disruptions to essential services66 67 and therefore subsequently advert excess deaths.

Our findings also show that capacity in healthcare settings, a core indicator of health system performance assessing available human resources and hospital beds in countries, was negatively related with excess COVID-19 deaths.

Recent evidence indicates that settings with fewer human resources in healthcare settings are more vulnerable to excess COVID-19 deaths due to greater disruptions to essential health services.68

Therefore, considering that there was an effect without correction for multiple hypotheses, our finding for healthcare capacity, the results from the sensitivity analysis and prior research, there is evidence that investments in health systems can modulate pandemic outcomes.

It is important to amass timely and accurate global data to more fully measure the strength and resilience of health systems to respond to infectious disease emergencies, while also meeting countries’ full set of health needs.

Future studies should re-evaluate the role of health systems in supporting effective pandemic responses as global metrics of health system capacities improve.

Furthermore, we observed that other core GHS capacities, adherence to global norms and risk environment, not regularly assessed by other measures of pandemic preparedness were associated with diminished mortality.

In regard to adherence to international norms, our findings provide empirical evidence that cross-border agreements are beneficial during a pandemic.

For example, countries in the European Union shared the burden of the pandemic, as countries accepted hospitalised patients from overwhelmed countries, borders remained open to healthcare workers and those seeking medical care, and they shared essential knowledge.69

While these cross-border agreements have been shown to be difficult to implement due to differing country-specific rules and priorities,70 our results provide quantitative evidence that these collaborations can play a critical role in adverting deaths and major disruptions in care.

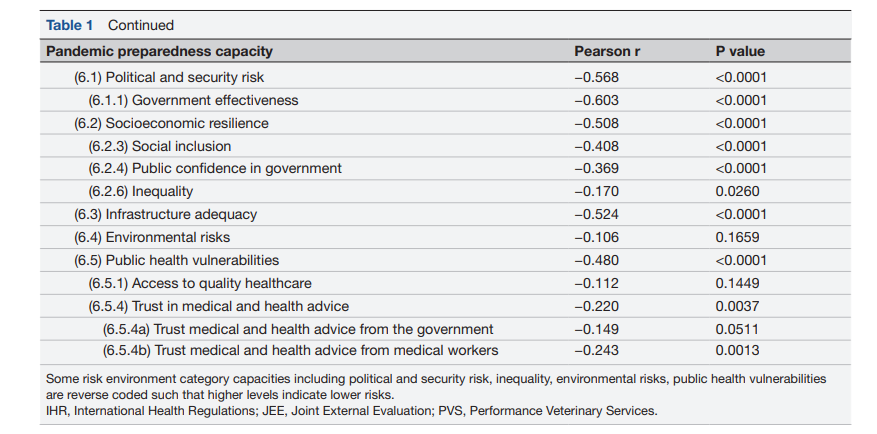

Finally, the GHS Index category that had the strongest and consistent relationship with excess COVID-19 mortality was the risk environment.

The risk environment category assesses the socioeconomic, political, regulatory and ecological factors that increase vulnerability to outbreaks.71

A notable risk environment indicator that was associated with excess deaths was government effectiveness, which captures governments’ abilities to efficiently formulate and implement policies and accountability of public officials.

This indicator was likely an important factor in cross-country variation of excess deaths as this capacity provides a framework for proactive policies to ensure supply of medical equipment and rapid implementation of interventions.72 73

We also found that levels of inequalities and social exclusion were each associated with fewer excess deaths.

Across various countries investigations have highlighted that COVID-19 disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, as they are the least protected and often face the greatest risk from COVID-19.74–77

These discrepancies further propagate the pandemic and serve to exacerbate existing inequalities.78

Countries with lower levels of inequality were likely able to craft equitable responses that contributed to lower excess deaths and thus future preparedness plans should include measures to reduce disparities.79

A notable risk environment indicator that was associated with excess deaths was government effectiveness, which captures governments’ abilities to efficiently formulate and implement policies and accountability of public officials.

The risk environment may be a primary reason why the US response was disjointed compared with other high-income countries.

Despite the US ranking the highest in the GHS Index, the USA had the 41st smallest CMR and 30th largest risk environment score among the 57 high-income countries included in this analysis.

While countries such as Iceland, Australia and New Zealand had the top 4 lowest CMRs and in the top 20 in risk environment.

Evidence suggests that New Zealand was able to mount a success response because of strong leadership coordinating with many institutions to implement response measures in real-time, prioritisation of vulnerable populations in responses, effective communication strategies that induced population-wide support of responses and swift institutional approval of pandemic tools.80 81

Evidence suggests that New Zealand was able to mount a success response because of strong leadership coordinating with many institutions to implement response measures in real-time …

Responses in Australia82 and Iceland83 also benefited from similarly strong, rapid and coordinated responses.

While the USA has a multitude of pandemic capacities, the US response was fragmented due to

- states implementing different control strategies,84

- early institutional rules preventing rapid mobilisation of diagnostic equipment 85 and

- mixed communication that potentially harmed compliance in response measures.86

While the USA has a multitude of pandemic capacities, the US response was fragmented due to:(1) states implementing different control strategies,84; (2) early institutional rules preventing rapid mobilisation of diagnostic equipment 85 and (3) mixed communication that potentially harmed compliance in response measures.86

Overall, our analysis confirms that after adjustment for population age distribution and under-reporting of deaths, there are the expected country-level relationships between pandemic preparedness capacities and COVID-19 outcomes.

Even after adjustment for GDP per capita as a confounder, owing to countries with greater income potentially having more resources to augment capacities and to allocate to health services to advert mortality, many capacities remained associated with reduced COVID-19 mortality.

Our findings were also confirmed in our sensitivity analysis, where we further adjust for country-level differences in COVID-19 mitigation policies.

These findings reinforce that regardless of income levels and real-time pandemic response policies, existing pandemic preparedness capacities provide countries with a directly modifiable tool that they can build to avert mortality in the context of an evolving pandemic.

While our findings confirm the expected relationships between many pandemic preparedness capacities and COVID-19 outcomes, we identified a few capacities that were not associated with excess deaths.

For example, previous studies have identified that greater levels are trust are associated with reduced COVID-19 burden,23 87–89 but we did not observe this relationship.

However, we did find a relationship for public confidence in government, an analogous form of intuitional support and cooperation but confidence differs from trust in that it is built off previous evidence and experience.87

Thus, our analyses still provide some evidence that social and governmental support are important factors for responses to the pandemic.

Future studies should continue to explore the country-level relationship between trust and COVID-19, and other capacities that were not related to excess deaths in this study including healthcare access and intervention planning.

Lastly, we found that the relationships between preparedness capacities and excess mortality became null when using data from the WHO and The Economist.

A major contributor to the change in relationships is due to substantial differences in estimates between the three groups.

For example, in countries with low GHS scores (<40), excess mortality estimates are generally twofold to threefold greater when comparing IHME to WHO estimates.

Since these locations generally do not have reliable cause of death data, all three modelling groups rely on statistical models with various covariates and assumptions.

Our initial investigations have shown that CMRs from the WHO and The Economist are moderately correlated with reported COVID-19 deaths while there is no correlation for CMRs produced from IHME estimates.

Since under-reporting of COVID-19 deaths is a common problem in countries with low GHS scores, with postmortem surveillance studies in Africa indicating that deaths are undercounted by a factor of 10 ,90 91 the potential greater reliance on reported COVID-19 deaths by WHO and The Economist may partially explain the different estimates in countries with low GHS scores.

Besides varying reliance on reported deaths, all three modelling groups also use different sets of covariates to produce estimates in locations without data.

Overall, this sensitivity analysis revealed that pandemic preparedness capacities are not associated with worse pandemic outcomes and that there is a critical need for improved and robust pandemic outcome measures.

Conclusion

The measures within the GHS Index were not intended to serve as a predictive model of how countries will respond in a crisis, but an inventory of the resources and plans available within each nation.

This analysis demonstrates that having greater national level health security capacities, as measured by the GHS Index, is associated with lower excess COVID-19 mortality.

An established and regularly exercised response infrastructure is critical to address a health crisis, but so are the preventive measures that provide day-to-day services to ensure an accessible, equitable and capable health system for outbreak detection.