This is an excerpt of the Section 2 of the report “Our duty of care — A global call to action to protect the mental health of health and care workers”

Site editor:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Health Transformation — research institute, strategy and implementation

October 5, 2022

Our duty of care

A global call to action to protect the mental health of health and care workers

WISH 2022 Forum on the Mental Health of Health and Care Workers

Hanan F Abdul Rahim Meredith Fendt-Newlin Sanaa T Al-Harahsheh Jim Campbell

2022

Safeguarding the mental health of health and care workers requires individual- and organizational-level interventions.

Findings from the Magnet4Europe project, a four-year initiative to improve mental health and wellbeing among health professionals, showed that physicians and nurses placed a higher priority for their wellbeing on organizational changes — including improved staffing, reducing documentation burdens and allowing more time with patients — over resilience training or meditation space.[1]

In the COVID-19 pandemic, health workers reported the need for respite breaks, concerns about access to full vaccine and effective PPE, and the need for redeployment training as key factors for burnout and retention.[2]

- Organizational-level interventions

- Psychosocial interventions

1.Organizational-level interventions

WHO and International Labour Organization (ILO) have issued guidance for the occupational safety and health of workers in public health emergencies, including job/task rotations to reduce exposure to risk factors and strains, scenario-specific training on standard operating procedures to enable workers to deal with the emergency competently and effectively, and making available adequate and properly fitted PPE.[1]

The guidelines also emphasize the importance of good communication and clear information-sharing to give workers a sense of control and a chance to express concerns.

Updated interim guidance by WHO and ILO (February 2021) addresses occupational risks “amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic” — including psychological distress, stigma, discrimination, physical and psychological violence and harassment.[2]

Although the guidelines do not specify mental health risks, the proposed measures target worker concerns and risk factors associated with poor mental health outcomes (as outlined in Section 1).

Guidance for the health and safety of workers in the COVID-19 pandemic includes:

- safe staffing levels and fair allocation of workloads

- rest breaks and time off between shifts

- supportive supervision, and training on Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) practices

- paid leave and policies for workers to stay home without loss of income in case of being unwell, or in self-quarantine and self-isolation.

Box 3. Australia:

Government investment in mental health services for health and care workers

In response to the pandemic exacerbating existing mental health concerns in health and care workers, the Australian Federal Government boosted investment and took co-ordinated action with a national framework — Every Doctor, Every Setting — to scale up interventions for the mental health and wellbeing of the health and care workforce as a national priority.[1]

One key initiative borne out of this investment is TEN — The Essential Network for Health Professionals,[2] a digital-first mental health service that uses an integrated blended care model where health and care workers can access a range of self-guided resources and/or person-to-person services.

To date, TEN has reached over 52,000 people. Preliminary data indicated a troubling mental health landscape.[3]

Symptoms of psychological distress were reported by 84 percent; more than half reported moderate (or greater) depression, anxiety and impaired functioning; and 32 percent reported clinically significant post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.

More than 90 percent reported burnout symptoms such as disengagement and exhaustion. Doctors and nurses appear to be the most affected.

Wide-ranging stakeholder engagement and observational research assessing the acceptability and usability of TEN has been used to optimize the uptake and continuous improvement of this initiative.[4] [5]

In almost all of these consultations, stigma was reported as the main barrier to accessing mental health services for all occupations, with doctors in particular reporting concerns regarding mandatory reporting.

One respondent stated:

“I think there’s also a fear of repercussion that if you divulge that you’ve got this mental illness or mental health issues … you could potentially lose your job.”

In response, TEN is confidential and can be accessed anonymously; service usage is not linked to the national Medicare system that generates permanent health records accessible by colleagues.

National programs to support health and care workers’ mental health should be accessible, tailored to individual needs, confidential and monitored for effectiveness.

2.Psychosocial interventions

Evidence is limited on effective interventions for improving the mental health of health and care workers in mass outbreak situations.

While there are studies on a range of individual- or group-level psychosocial interventions delivered to health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a dearth of high-quality studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions delivered in previous mass outbreak settings.[1]

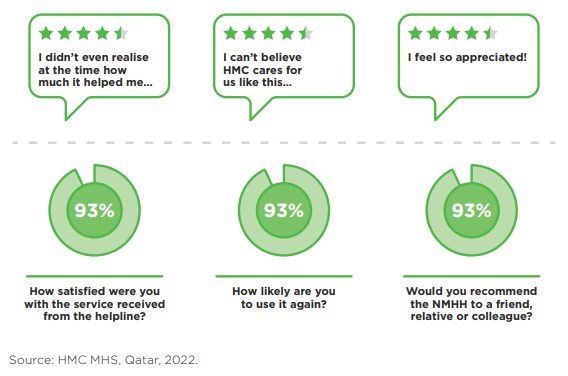

Box 4. Qatar:

Insights from a national mental health helpline

In April 2020, the Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) Mental Health Service (MHS), in collaboration with the Ministry of Public Health and Primary Health Care Corporation (PHCC), established the National Mental Health Helpline (NMHH), aimed at offering easy, confidential and timely access to mental health support for health and care workers and the general public.

The NMHH has a fully integrated interdisciplinary team, co-ordinated by a team of nurses trained as triage and shift co-ordinators.

This frontline triage team is supported by a team of psychiatrists and interventional psychologists, ensuring that callers have access to psychological intervention and treatment when necessary.

All staff are trained using a standardized evidence-based resource pack to ensure that they are adequately prepared to offer support. As mental health needs increased in both complexity and scope as the pandemic wore on, training was adapted in 2021 to include grief and compassion fatigue.

The HMC MHS actively promoted the NMHH through posters across HMC and PHCC, awareness videos on social media, the System Wide Incident Command and Control (SWICC)/Tactical Command group messages, and via embedding a message to HMC screen savers.

Staff whose managers submitted their contact information also received a standardized psychosocial support call, offering positive coping strategies.

In addition, the NMHH team also offered incident debriefing in response to incidents in clinical areas, as well as a variety of wellbeing educational webinars.

The NMHH dealt with more than 43,000 calls in the first two years of operation; though only about 1 percent of calls each month are from health and care workers, even though their calls are prioritized.

However, the NMHH’s other activities have reached just over 10,000 health and care workers since April 2020.

Source: HMC MHS, Qatar, 2022.

In our systematic examination of reviews (as described in Section 1), only two were identified as looking at the effectiveness of psychological support and psychosocial interventions …

… to mitigate adverse mental health outcomes among health workers in disaster settings and outbreaks.[1] [2]

In our systematic examination of reviews (as described in Section 1), only two were identified as looking at the effectiveness of psychological support and psychosocial interventions to mitigate adverse mental health outcomes among health workers in disaster settings and outbreaks.[1] [2]

In those reviews, interventions based on evidence-based protocols involving individual – and group-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) were effective in reducing PTSD and anxiety, while single-session interventions were less successful.

In those reviews, interventions based on evidence-based protocols involving individual — and group-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) were effective in reducing PTSD and anxiety, while single-session interventions were less successful.

Despite methodological concerns, the largest statistical and clinical differences appeared to result from comprehensive interventions that included clear mental health and psychosocial components, as well as increased staffing, PPE provision and training.[3] [4]

There is evidence that staff with the highest burden of mental health conditions were the least likely to request or receive support.[5]

This highlights the importance of systematic and clear pathways to mental health services that safeguard confidentiality and protect against stigmatization.

There is evidence that staff with the highest burden of mental health conditions were the least likely to request or receive support.[5]This highlights the importance of systematic and clear pathways to mental health services that safeguard confidentiality and protect against stigmatization.

In its updated guidance on mental wellbeing at work, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK recommended providing mechanisms for early and confidential identification and management of mental health needs, ensuring that workers are aware of support resources through dedicated focal points, with referral options that are free from stigma (see Box 5).[6]

Box 5.

Stigma associated with seeking mental health support

Stigma is a powerful social process associated with labeling, stereotyping and separation, leading to status loss and discrimination within a context of power.[1]

Stigma toward persons suffering from mental illnesses is widespread and can influence the help-seeking behavior of all groups, particularly health and care workers.[2] [3]

Health and care workers are more prone to suffer in silence due to the perceived stigma associated with suffering ‘mental illness’, as well as the fear of losing their medical license.

This hesitation to seek help or disclose mental health problems can lead to an over-reliance on self-treatment and low peer assessment.[4] [5]

In medical practice, admitting to a mental condition can sometimes lead to ostracism and judgment from colleagues.[6] [7] [8]

Many are concerned that a diagnosis of depression or similar mental illness may imply that they are unable to provide quality care; they fear losing their community’s respect and their own reputation.

As a result, their livelihood and families’ financial security may be jeopardized.[9] [10]

Therefore, interventions targeting this group should focus on combating the stigma associated with seeking treatment and encourage the healthcare workforce to speak up when experiencing mental ill health.

The obligation of ‘duty of care’ includes both physical and mental health protections

- Governments and employers have a responsibility to provide a safe and healthy working environment for all staff and to make reasonable adjustments to meet the specific needs of individuals, which is now agreed by Member States as the fifth fundamental principle and right at work.[1]

- It is the mandated obligation of the system to protect workers[2] through the prevention of harmful physical or mental stress due to conditions of work, and to recognize the right of everyone to a world of work free from violence and harassment, including gender-based violence and harassment.[3]

It is vital to focus on system-level prevention of risks and hazards to health and care workers’ mental health and wellbeing.

Without this, individual psychosocial interventions will be futile, since the duration of effects are time-limited, and workers’ application of individual coping strategies or resilience training will be minimized in working environments that continue to do harm.

This should be a high priority in times of crisis, but also on an ongoing basis.

Preparing health and care workers for the demands and psychological impacts before, during and after events such as COVID-19 is essential to minimize risks and prevent mental distress.[4]

Findings of our review point to wider and systemic risk factors leading to mental health issues and burnout of staff.

Individual interventions should be delivered alongside efforts to protect the functioning of the health system, ensure safe and decent working conditions to retain workers and, in turn, preserve their motivation to continue protecting the health of others.[5]

WHO and WHPA found that across five global health workforce professions, personnel interpret the lack of systemic protection mechanisms for their safety and security, health and wellbeing as being undervalued.[6]

In May 2022, the Seventy-fifth World Health Assembly adopted the resolution on human resources for health (WHA75.17), calling on Member States to fulfill a duty of care by using the WHO global health and care worker compact (the Global Care Compact)[7] in line with the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel.[8]

The Global Care Compact compiles and references existing international legal instruments, labor laws and regulations, and States’ obligations, providing technical guidance on how to protect health and care workers and safeguard their rights.

Its framework for action encompasses:

- Preventing harm from dangers and hazards in work, with infection prevention and control; provision of mental health and psychosocial support; protection in fragile, conflict and vulnerable situations; and protection from violence and harassment.

- Providing support with fair and equitable compensation and social protection in enabling work environments; ensuring time for workers to access the care they need.

- Promoting inclusivity of rights, protections and enablers for equal treatment and non discrimination.

- Safeguarding rights to: collective bargaining; individual empowerment; whistleblower protections; and freedom from retaliation.

Promoting enabling practice environments where positive mental health and wellbeing of the workforce thrive

In addition to their legal obligations for duty of care, employers should also be proactive in developing a supportive culture.

Enabling practice environments — health and care settings that support excellence and decent work conditions — have the power to attract and retain staff, provide quality patient care and strengthen the health and care sector as a whole, according to the World Health Professions Alliance.[9]

To transform workplace culture to empower health and care workers, organizations must:[10] [11] [12]

- develop organizational policies that are equitable and inclusive.

- ensure that health workers are not deterred from seeking appropriate care for their physical health, mental health and/or substance use.

- encourage a fair and supportive workplace environment with a commitment to occupational safety and health.

- provide educational opportunities.

One successful example is the International Pharmaceutical Federation’s FIPWiSE toolkit for positive practice environments for women in science and education.[13]

This toolkit identifies and addresses inequalities in workplace environments that affect women in these fields.

It has been implemented in countries around the world and provides an example for recruiting, rewarding and retaining women in the workforce.

Box 6.

What COVID-19 means for the future of the workforce

“I feel like giving up. I care so much for my patients but how long can I keep this up?”

Primary care practitioner, USA

The physical and mental strains — and levels of reported burnout — experienced by health and care workers responding to COVID-19 raise questions about the future of the workforce.

Over the course of the pandemic, these workers were alternately valorized as ‘heroes’ and vilified, even to the point of physical attacks.[1]

Between January 2020 and June 2022, there were 1,613 reported (to WHO) attacks on healthcare, including more than 700 on health and care personnel.[2]

These attacks deprive people of urgently needed care, endanger health and care workers, and undermine health systems.

In the UK, the British Medical Association (BMA) warned of impending staff departures due to stress and burnout, and the adverse impact on patient safety.[3]

In a May 2020 BMA survey, 15 percent of respondents said they planned to leave the National Health Service (NHS), take early retirement, or work elsewhere once normal services were resumed. By February 2021:

· 18 percent of doctors were “more likely” to consider leaving the NHS for another career within a year.

· 26 percent were more likely to take early retirement.

· 26 percent were more likely to take a career break within a year.[4]

Similarly, the NHS Staff Survey 2021 (of more than 600,000 workers[5]) found:

· 31 percent thought often of leaving the organization.

· 23 percent would probably look for a job at a new organization in the next 12 months.

· 17 percent would leave as soon as they could find another job.[6]

In the US, a survey supported by the American Medical Association of more than 20,000 health and care workers across 124 institutions between July and December 2020 found the reported intention to leave practice within the next two years at 24 percent among doctors and 40 percent among nurses.[7]

Burnout, workload and stresses associated with COVID-19 explained the intent to leave or to reduce working hours.

Several studies showed that the mental health of nurses was more adversely affected in the pandemic compared to other health professions.

Between January 2020 and April 2022, news articles pertaining to 76 countries reported industrial actions by health workers, including threats of strikes.[8]

Overall, the main actors in industrial actions in 2020 and 2021 were nurses, who comprise 59 percent of health workers globally.

Reasons for the action included lack of risk allowance, insurance, overtime payment, or delayed salary; shortages in staff, equipment, supplies; and poor working conditions in general.

The International Council of Nurses has warned that the estimated 5.9 million pre-pandemic shortage of nurses has been exacerbated by the pandemic and could lead to more severe shortages, especially in lower and lower-middle income countries.[9]

In responding to this shortage, the report calls for shifting the focus of policies from individual-level interventions to ones that create a healthier and more productive working environment (p. 28):

“An essential part of this response must be to shift the policy, professional and management focus from individual nurses having to ‘cope’ and ‘be resilient’ with unbearable pandemic-driven work burdens, to one where employers and organisations take responsibility for creating and maintaining supportive working conditions and adequate staffing.”

References

See the original publication

Jim Campbell Director, Health Workforce Department, World Health Organization (WHO)

Hanan F. Abdul Rahim Dean, College of Health Sciences, Qatar University

N Sultana Afdhal Chief Executive Officer, World Innovation Summit for Health (WISH)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Forum advisory board for this paper was chaired by Mr Jim Campbell, Director of the Health Workforce Department, World Health Organization (WHO), and Dr Hanan Abdul Rahim, Dean of the College of Health Sciences, Qatar University.

The paper was written by Dr Hanan Abdul Rahim in collaboration with Mr Jim Campbell and Dr Meredith Fendt-Newlin, WHO, and Dr Sanaa T Al-Harahsheh, WISH.

Sincere thanks are extended to the members of the advisory board of the WISH 2022 Forum on the Mental Health of Health and Care Workers, who contributed their unique insights to this report:

- Mr Howard Catton, International Council of Nurses, Switzerland

- Dr Catherine Duggan, International Pharmaceutical Federation,

Netherlands - Mr Paul Farmer, Mind, UK

- Dr Cindy Frias, Institute of Neurosciences, Hospital Clinic

of Barcelona, Spain - Mrs Victoria Hornby, Mental Health Innovations, UK

- Dr Dévora Kestel, WHO, Mental Health and Substance

Use Department, Switzerland - Prof Yousef Khader, Jordan University of Science and

Technology, Jordan - Mr Iain Tulley, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

We also extend our thanks for the contributions to this report made by:

• Dr Peter Baldwin, Black Dog Institute, Australia

• Dr Matthew Coleshill, Black Dog Institute, Australia

• Dr Giorgio Cometto, WHO, Health Workforce

Department, Switzerland

• Dr Matías Irarrázaval Domínguez, Pan American Health

Organization (PAHO), Department of Noncommunicable Diseases

and Mental Health, USA

• Mr Mohamed Elgamal, Qatar University, Qatar

• Dr Jen Hall, WHO, Country Office, Fiji

• Mr Ayman Ibrahim, Qatar University, Qatar

• Ms Catherine Kane, WHO, Health Workforce

Department, Switzerland

• Dr Salma Khaled, Social and Economic Survey Research Institute,

Qatar University, Qatar

RELATED ARTICLES