This is an excerpt of the publication below, with the title above, focusing on the topic in question. “Imagining the Future of Primary Care: A Global Look at Innovative Health Care Delivery”

NEJM Catalyst

Pratik Pinal Doshi, BS, MS, Satasuk Joy Bhosai, MD, MPH, Don Goldmann, MD, and Krishna Udayakumar, MD, MBA

February 22, 2021

medicalfuturist

Edited by

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

The Health Revolution Institute

Digital, Health and Care Revolution

June 18, 2022

EXCERPT

Our research team at Innovations in Healthcare (IiH) — a nonprofit founded by Duke University, McKinsey & Company, and the World Economic Forum — identified and curated a network of 99 global health innovators across 90 countries through a systematic scouting process.

Using a multimodal approach that included a literature review, key stakeholder input, and the Delphi Method, …

… we selected four that were considered most innovative, with guidance from global experts.

While accountable care frameworks — defined as those that align health financing and regulatory systems with person-centered care reforms that enable improvements in population health — are not the only way to innovate in primary care, special attention was made to these models given their tremendous growth within the United States and around the world in recent years.,

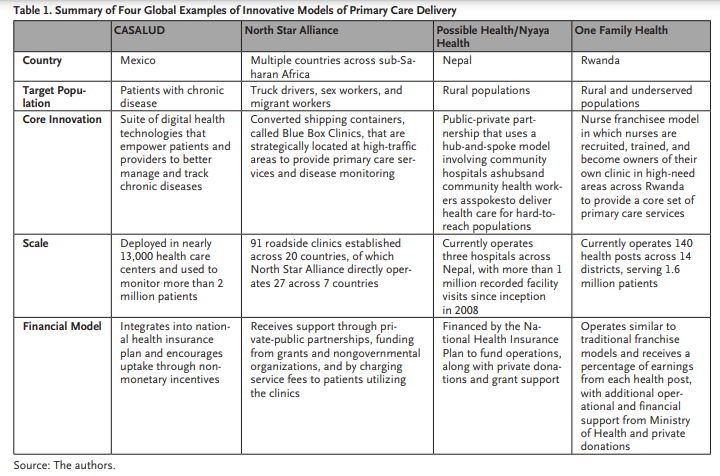

These four organizations are:

- CASALUD in Mexico,

- North Star Alliance involving multiple countries in sub-Saharan Africa,

- Possible and Nyaya Health in Nepal, and

- One Family Health in Rwanda ( Table 1).

Each of these models demonstrates innovative approaches in four major domains

- care delivery innovations,

- patient-centered organizational competencies,

- streamlined organizational policies, and

- alternative financing and payment models ,,

… using distinct methods to increase access to primary care services and presents an opportunity to see how such models can be adapted to other health systems.

One Family Health: Empowering Clinicians through Alternative Financing Models

The premise of its operational model centers on developing nurse franchisees who would own and operate their own clinic in rural communities.

As the franchisor, One Family Health provides financing, consistent medication supply, training, and quality assurance to each franchised clinic.

OFH was established as a public-private partnership with the Ministry of Health in Rwanda. With the support of the Ministry, localities across Rwanda that have low access to health services are identified and targeted for potential to establish a clinic.

OFH then sets out to recruit, interview, and train nurses who would be interested in working in that region.

These nurses are trained in providing basic primary care services, managing noncommunicable diseases, and setting up financial and business operations.

These nurses are trained in providing basic primary care services, managing noncommunicable diseases, and setting up financial and business operations.

Franchisee nurses are required to make a down payment (usually around US$500) to OFH to secure a health post, and then pay a percentage of revenues to OFH per month once the clinics are operational.

For context, the average annual salary of a nurse practitioner in urban areas of Rwanda is about US$3,000-US$5,000, and the cost of opening an OFH franchise is meant to signal financial and personal commitment from the nurses.

By the end of 2020, OFH will have established 130 health posts across 14 districts, serving more than 1.6 million patients.

Their goal is to establish 500 clinics across the country, yet they have faced some delays in expansion due to Covid-19-related restrictions and fundraising challenges.

By the end of 2020, OFH will have established 130 health posts across 14 districts, serving more than 1.6 million patients.

This public-private partnership is estimated to save the Ministry of Health US$3,600 per clinic site per year, which will amount to US$9 million in savings when fully scaled.

This can represent a significant cost-saving given the entire primary care budget for Rwanda is approximately US$80 million (2019), and given that health centers and posts represent about 15% this budget.

To ensure affordability for the patients, OFH clinics participate in the community-based health insurance (Mutuelle de Santé), which covers about 90% of the population.

This allows insured members to pay about US$0.30 co-pay (which is similar to the amount paid at government health centers), with patients not covered through this insurance program paying between US$2-US$4 for the full cost of services.

To ensure affordability for the patients, OFH clinics participate in the community-based health insurance (Mutuelle de Santé), which covers about 90% of the population.

This allows insured members to pay about US$0.30 co-pay …

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version

Imagining the Future of Primary Care: A Global Look at Innovative Health Care Delivery

Lessons from provider organizations in Mexico, sub-Saharan Africa, Nepal, and Rwanda offer examples of approaches that can be adopted to improve primary and preventive care in the United States.

NEJM Catalyst

Pratik Pinal Doshi, BS, MS, Satasuk Joy Bhosai, MD, MPH, Don Goldmann, MD, and Krishna Udayakumar, MD, MBA

February 22, 2021

medicalfuturist

Digital version edited by

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

The Health Revolution Institute

Digital, Health and Care Revolution

June 18, 2022

Summary

An analysis by Duke Global Health researchers at Innovations in Healthcare reveals innovative approaches to primary care delivery by providers in countries across the globe.

The focus is on systems that embrace accountable care frameworks within four major domains:

- care delivery innovations,

- patient-centered organizational competencies,

- streamlined organizational policies, and

- alternative financing and payment models.

Successes by these organizations may inform and influence current and future public health and primary care practices in the United States.

Structure of the publication

- Introduction

- CASALUD: Leveraging Digital Tools for Health Care Delivery (Mexico)

- North Star Alliance: Developing Organization Competencies to Align with Patients (Multiple countries across sub-Saharan Africa)

- Nyaya Health and Possible Health: Aligning Policies and Payments to Streamline Health Systems (Nepal)

- One Family Health: Empowering Clinicians through Alternative Financing Models (Rwanda)

- Lessons Learned and Adapting Models for a U.S. Market

- Looking Ahead

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

Imagining the Future of Primary Care: A Global Look at Innovative Health Care Delivery

NEJM Catalyst

Pratik Pinal Doshi, BS, MS, Satasuk Joy Bhosai, MD, MPH, Don Goldmann, MD, and Krishna Udayakumar, MD, MBA

February 22, 2021

Introduction

The disease and health care cost burden in the United States has significantly shifted over the past 40 years.

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) have replaced infectious diseases as the primary cause of morbidity and mortality across the country, with similar trends appearing globally.

This movement away from acute pathologies to diseases that require long-term monitoring has significantly increased the cost burden of health care.

The disease and health care cost burden in the United States has significantly shifted over the past 40 years.

This movement away from acute pathologies to diseases that require long-term monitoring -such as NCDs — has significantly increased the cost burden of health care.

The United States currently devotes more than 17% of the gross domestic product (GDP) to health care, of which diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and low back and neck pain make up the three diseases with the highest overall amount spent.,

These three diseases, along with other chronic disease states that contribute to the rising cost burden of health care, are best addressed through effective primary care providers.

These three diseases — diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and low back and neck pain, — along with other chronic disease states that contribute to the rising cost burden of health care, are best addressed through effective primary care providers.

While primary care providers are well-positioned to deliver longitudinal care, there remains a growing shortage of these physicians to meet current and future populations’ demands.

Our research team at Innovations in Healthcare (IiH) — a nonprofit founded by Duke University, McKinsey & Company, and the World Economic Forum — identified and curated a network of 99 global health innovators across 90 countries through a systematic scouting process.

Using a multimodal approach that included a literature review, key stakeholder input, and the Delphi Method, …

… we selected four that were considered most innovative, with guidance from global experts.

While accountable care frameworks — defined as those that align health financing and regulatory systems with person-centered care reforms that enable improvements in population health — are not the only way to innovate in primary care, special attention was made to these models given their tremendous growth within the United States and around the world in recent years.,

While accountable care frameworks … are not the only way to innovate in primary care, special attention was made to these models given their tremendous growth within the United States and around the world in recent years.,

These four organizations are:

- CASALUD in Mexico,

- North Star Alliance involving multiple countries in sub-Saharan Africa,

- Possible and Nyaya Health in Nepal, and

- One Family Health in Rwanda ( Table 1).

Each of these models demonstrates innovative approaches in four major domains

- care delivery innovations,

- patient-centered organizational competencies,

- streamlined organizational policies, and

- alternative financing and payment models ,,

… using distinct methods to increase access to primary care services and presents an opportunity to see how such models can be adapted to other health systems.

CASALUD: Leveraging Digital Tools for Health Care Delivery

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as Mexico — and even within the United States — there is a constant shortage of trained health care workers to meet the demands of a growing and aging population.

Mexico has faced a rapid increase in rates of noncommunicable diseases.

Within the 10 years from 2009 to 2019, mortality rates due to ischemic heart disease and diabetes have increased by 48% and 53.5%, respectively, and are the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years within Mexico.,

A survey conducted in 2006 to estimate the prevalence of diabetes found that more than half of the people surveyed were not aware of their diagnosis, suggesting that the growth in disease burden is compounded by the lack of access to health care.,

Built on the belief that preventive care innovations can improve noncommunicable disease management, CASALUD has created a suite of digital technologies that strengthen efficiency and quality of care at the primary care clinic while also shifting more care to the patient’s own home and community.

CASALUD presents an innovative and data-driven approach to help patients and primary care providers manage chronic diseases.

The entity — which combines the words for house ( casa) and health ( salud) — was developed in 2008 by Fundación Carlos Slim [the Carlos Slim Foundation] in partnership with the Mexico Ministry of Health.

Built on the belief that preventive care innovations can improve NCD management, CASALUD has created a suite of digital technologies that strengthen efficiency and quality of care at the primary care clinic while also shifting more care to the patient’s own home and community.,

These digital technologies are designed to empower the patient to take greater responsibility in managing their disease processes and are based on five major pillars:

(1) early prevention and detection of chronic diseases,

(2) evidence-based disease management,

(3) supply chain improvements,

(4) health care professional capacity development, and

(5) patient engagement through mHealth.,

In deploying MIDO, CASALUD recognized the need for better training programs for community health workers and clinicians to provide preventive counseling for patients based on their risk assessment.

CASALUD developed partnerships with U.S. institutions such as the National Academy of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, and Joslin Diabetes Center to develop clinical degree and certification programs.

As a part of the larger Fundación Carlos Slim, CASALUD was designed and operated with the intent of eventually handing operations over to the Mexican government.

With ever-changing political conditions, CASALUD has currently opted to continue providing technical and financial support to the program, but has transitioned all patient data to the Mexican federal government and its Ministry of Health under Mexico’s INSABI universal health coverage program (as well as the earlier Seguro Popular program).

CASALUD has been continuing to do randomized controlled trials to better track its outcomes, and is measuring end points such as frequency of consultations, monthly stock levels of drugs and supplies, clinical education, number of clinicians engaged in educations, and percentage of populations screened.

North Star Alliance: Developing Organization Competencies to Align with Patients

Beyond providing adequate health services in a given country, one of the larger systemic issues is how to make those services accessible to target patient segments or populations.

By understanding the behaviors and needs of specific groups of people, one can target services that align to a person’s lifestyle and behavior, increasing the utilization of these services and decreasing the cost of care.

This issue particularly came to light in the early 2000s when the World Food Programme and TNT Express, a logistics and transportation service, were attempting to deliver large quantities of food across sub-Saharan Africa.

At the time, HIV was quickly spreading across Africa and decimating the available workforce that these programs used to complete their operational goals. In response, North Star Alliance (NSA) was founded as a public-private partnership focused on delivering care to mobile workers in the region.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, truck drivers, sex workers, and other migratory workers comprise a major component of transnational migration and trade between adjacent countries, but they also serve as critical vectors of HIV spread, and, more recently, the spread of Ebola and Covid-19.,

As of 2020, NSA has established 91 roadside clinics in 20 countries; 27 of the clinics are currently operated independently by NSA in 10 countries.

The other clinics have been transitioned to local ministries of health and other service providers that still use NSA operational tools and services.

The core innovation driving North Star Alliance’s growth and success across multiple countries is its Blue Box Clinics.

These primary care clinics (many are physically adapted from standard shipping containers) are strategically located along major transport corridors that are likely to be hot spots of disease — such as ports, border crossings, or truck stops — as identified by local governments.

The core innovation driving NSA’s growth and success across multiple countries is its Blue Box Clinics.

These primary care clinics (many are physically adapted from standard shipping containers) are strategically located along major transport corridors that are likely to be hot spots of disease — such as ports, border crossings, or truck stops — as identified by local governments.

Each clinic offers flexible operating hours that are adjusted to the needs of the specific population and offer a wide range of primary care services such as HIV counseling, behavioral health services, sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment, and monitoring for noncommunicable diseases.

Furthermore, one major issue that NSA identified early in its scale-up of operations was that migratory workers often had trouble with continuity of care as health records could not be transferred across national borders.

To address this, NSA created a digital health ecosystem called COMETS (Corridor Medical Transfer System) that combines supply chain, health insurance, patient health records, and full functionality within each clinic that facilitates continuity of care.

In addition, NSA has been partnering with communities to expand the range of services provided at their clinics.

Through the Star Driver loyalty program, patients are encouraged to return to Blue Box clinics to receive both public health screenings and nonmedical services such as professional development activities and job training to improve self-esteem and a sense of community.

In 2019 alone, NSA served nearly 110,000 patients who accessed nearly 250,000 health services across the Blue Box clinics.

Of these patients, 28,000 were truck drivers and 37,000 were sex workers, about half of whom received STI testing and treatment and HIV counseling and testing.

In addition, NSA was able to provide behavioral counseling and mental health support to nearly 71,000 patients, with a total operating budget of €2.6 million (about US$3.2 million).,

Nyaya Health and Possible Health: Aligning Policies and Payments to Streamline Health Systems

To have efficient health systems, there needs to be synergy among all levels of providers, from community health workers to physicians to Ministries of Health.

Nyaya Health (later renamed Possible Health, and later still, the two became distinct organizations), a nonprofit founded in 2006 by U.S. medical students trying to find a way to deliver care to rural districts in Nepal, has grown to apply an integrated care approach based on strong public-private partnerships to provide coordinated and comprehensive care for rural and underserved populations.,

Nyaya Health initially focused on renovating and operationalizing abandoned government-owned hospitals in rural communities.

n the Achham district, for example, the Bayalapata district hospital had been abandoned for 30 years, leaving 260,000 people without access to a doctor and a 36-hour journey away from the major hospitals in the capital city of Kathmandu.

Nyaya Health built strong public-private partnerships and raised significant funds to renovate the Bayalapata Hospital, which reopened its doors in 2008.

Nyaya, with financial support from Possible, dedicated funds to improving management and care delivery through protocol standardization; hiring managers and staff for nonclinical duties; increasing accountability for health care providers to reduce overprescribing; and investing in project management technologies.

The approach has demonstrated success in providing affordable care and improving health outcomes in target areas.

Nyaya Health is able to provide community outreach to 245,000 people at a per capita cost of NPR340 (about US$3.05 in 2020).,

With fundraising support from Possible Health, government-funded grants, and other philanthropic partners they have an operating budget of about US$3.4 million (2019).

As of 2020, Nyaya Health has supported a cumulative 1 million patient visits since inception in 2008.

In the Bayalapata hub in the Achham district, the institutional birth rate was 30% in 2012 when efforts were made to increase maternal care and CHWs in the area, resulting in a rapid increase to 96% as of 2018.

Nyaya Health has also demonstrated a decrease in neonatal mortality per 1,000 live births from 14% in 2014 to 6% in 2016. Possible and Nyaya Health demonstrate not only the impact that integrated care delivery approaches can have, but also how local input should drive innovation and organizational changes.

One Family Health: Empowering Clinicians through Alternative Financing Models

The premise of its operational model centers on developing nurse franchisees who would own and operate their own clinic in rural communities.

As the franchisor, One Family Health provides financing, consistent medication supply, training, and quality assurance to each franchised clinic.

OFH was established as a public-private partnership with the Ministry of Health in Rwanda. With the support of the Ministry, localities across Rwanda that have low access to health services are identified and targeted for potential to establish a clinic.

OFH then sets out to recruit, interview, and train nurses who would be interested in working in that region.

These nurses are trained in providing basic primary care services, managing noncommunicable diseases, and setting up financial and business operations. Franchisee nurses are required to make a down payment (usually around US$500) to OFH to secure a health post, and then pay a percentage of revenues to OFH per month once the clinics are operational.

For context, the average annual salary of a nurse practitioner in urban areas of Rwanda is about US$3,000-US$5,000, and the cost of opening an OFH franchise is meant to signal financial and personal commitment from the nurses.

By the end of 2020, OFH will have established 130 health posts across 14 districts, serving more than 1.6 million patients.

Their goal is to establish 500 clinics across the country, yet they have faced some delays in expansion due to Covid-19-related restrictions and fundraising challenges.

This public-private partnership is estimated to save the Ministry of Health US$3,600 per clinic site per year, which will amount to US$9 million in savings when fully scaled.

This can represent a significant cost-saving given the entire primary care budget for Rwanda is approximately US$80 million (2019), and given that health centers and posts represent about 15% this budget.

To ensure affordability for the patients, OFH clinics participate in the community-based health insurance (Mutuelle de Santé), which covers about 90% of the population.

This allows insured members to pay about US$0.30 co-pay (which is similar to the amount paid at government health centers), with patients not covered through this insurance program paying between US$2-US$4 for the full cost of services.

Lessons Learned and Adapting Models for a U.S. Market

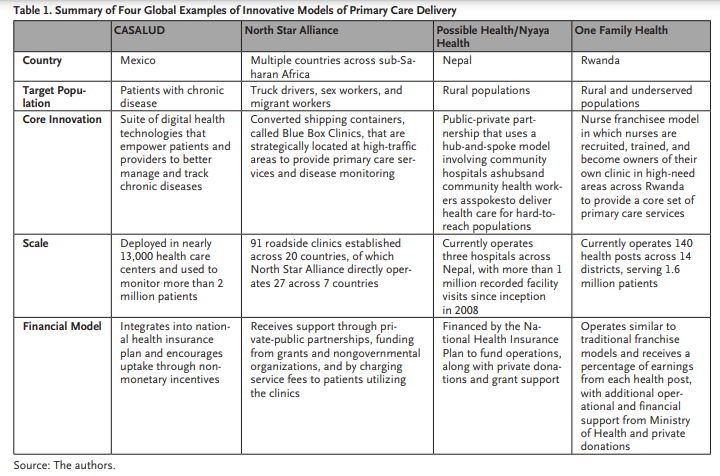

These innovations all are leading examples in their specific domain: delivery innovations, patient-centered organizational competencies, streamlined organizational policies, and alternative financing and payment models.

In addition, these four organizations share several key attributes that have facilitated their adoption and scale in their respective regions.

Given that the burden of diseases in these regions is distinct, each innovation has created solutions that are designed to be physically or virtually near the patient and to align with their behavior patterns.

The business models themselves provide standardization of operating procedures and reduction of variation in an effort to ensure quality, while keeping asset light to ensure effective scaling throughout geopolitical boundaries.

In addition, these solutions integrate data to drive decisions and insights, while providing patients with digital health technologies to better understand their health.

These PHC innovations all implemented a collaborative workforce that supports its delivery model.

The business models themselves provide standardization of operating procedures and reduction of variation in an effort to ensure quality, while keeping asset light to ensure effective scaling throughout geopolitical boundaries.

In addition, these solutions integrate data to drive decisions and insights, while providing patients with digital health technologies to better understand their health ( Table 2).

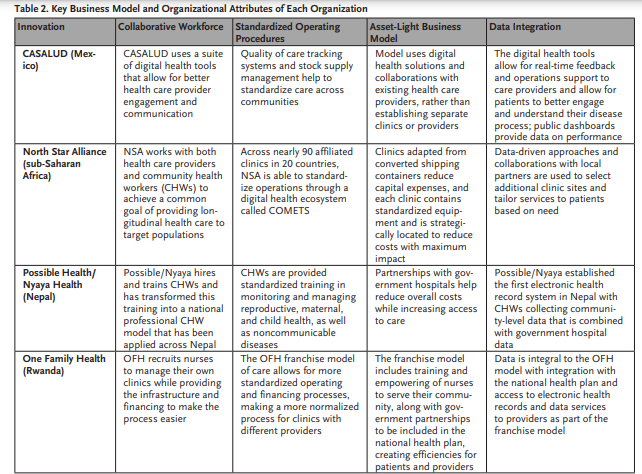

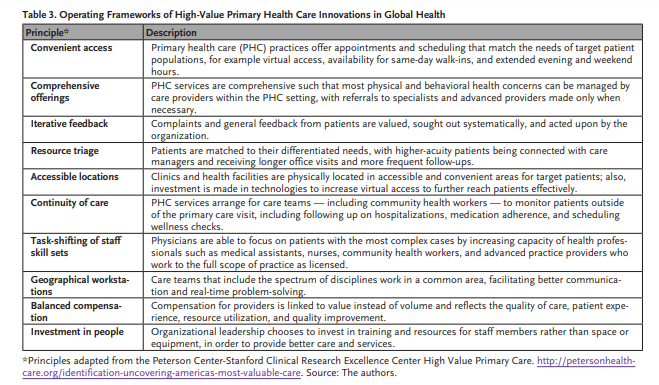

When adapting these lessons to the United States, there are several operating principles that can be applied to future health care delivery models.

While certain key indicators of successful primary care practices in the United States have been identified, our research team has adapted those characteristics to propose applications for a global framework for primary care delivery ( Table 3).

With these four examples of high-performing innovative PHC delivery and frameworks of high-value primary care, there are lessons and insights that we can apply to U.S. primary care delivery.

Health systems need to invest in clinical leadership while encouraging collaboration between providers and the community.

In addition, stakeholders may consider investing in interoperable technology infrastructure that provides longitudinal data and predictive insights, specifically for high-risk patients and their needs.

Pathways for multidisciplinary care could be made available to augment capabilities to care for patients in the community or home.

While there are other lessons that can be drawn from deep investigations of these innovative primary care models, these key lessons are critical elements for effective primary care in the United States.

Policy makers and payers can also benefit and learn from this global investigation of PHC delivery.

The four organizations each included well-defined financing structures as part of their business models that supported their mission and was in line with the needs of their target population.

For example, One Family Health utilized a nurse-franchise model and formed strategic partnerships with the Ministry of Health that allowed not only for expanded access to health services, but also the ability to offer those services at a lower rate while maintaining a sustainable business model.

Possible Health/Nyaya Health employs community health workers and data-driven decision-making that allows the CHWs to reach more patients and provide greater continuity while still keeping costs manageable.

Although operating these models in LMICs is significantly cheaper than a similar operation in the United States, there is still significant cost savings that can be gained by developing new modes of care delivery.

Policy makers and payers in the United States can create tools to track financial and health data to better monitor costs, revenues, and utilization rates that are correlated with health outcomes.

Additionally, they can provide stepwise, predictable approaches to payment model implementation that emphasizes higher value in care while developing evidence to guide future reform.

Of course, on a larger scale, there is a greater need to develop better paradigms that can effectively evaluate the impact of certain innovations.

Impact metrics such as number of lives saved are not commonly measured or reported globally. In addition, many reported outcome metrics are observational associations, and causational inferences are difficult to determine.

Given the variability in innovations and differences in measurement and evaluation of the spread and impact of organizations, there is need for future research to develop frameworks and evaluation metrics for health service innovations globally.

Looking Ahead

High-quality innovative approaches in primary health care are critically important to strengthen health systems and improve patient health outcomes.

By learning from leading examples of innovative global PHC models, health providers and key stakeholders can support the design of improved care delivery models at a lower cost burden to the health system and patients.

The future of primary health care will involve a patient-centric, connected health system supported by mobile technologies, and will align policies and financing to deliver high-quality care to more people.

About the authors

Pratik Pinal Doshi, BS, MS

- Medical Student, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Research Assistant, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke Global Health Innovation Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Satasuk Joy Bhosai, MD, MPH

- Chief of Digital Health and Strategy, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Associate Director, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke Global Health Innovation Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Don Goldmann, MD

- Chief Scientific Officer, Emeritus, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Professor of Pediatrics, Part-Time, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Professor of Epidemiology, Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Senior Advisor, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke Global Health Innovation Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Krishna Udayakumar, MD, MBA

- Founding Director, Duke Global Health Innovation Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Executive Core Faculty, Duke University Center for Health Policy, Durham, North Carolina, USA