BCG – Boston Consulting Group

By Ben Horner, Wouter van Leeuwen, Maggie Larkin, Julia Baker, and Stefan Larsson

SEPTEMBER 03, 2019

This is an excerpt from the report “Paying for Value in Health Care” published in September 2019, based on the chapter: “Characteristics of Succesful Payment Initiatives” edited by Joaquim Cardoso.

(VBHC: Value Based Health Care)

Characteristics of Successful Payment Initiatives

Of the 30 value-based payment initiatives we studied,

- about half reported quantified improvements in both quality and costs,

- a quarter reported improvements but without rigorous assessment, and

- another quarter reported mixed results or no improvement in health care value.

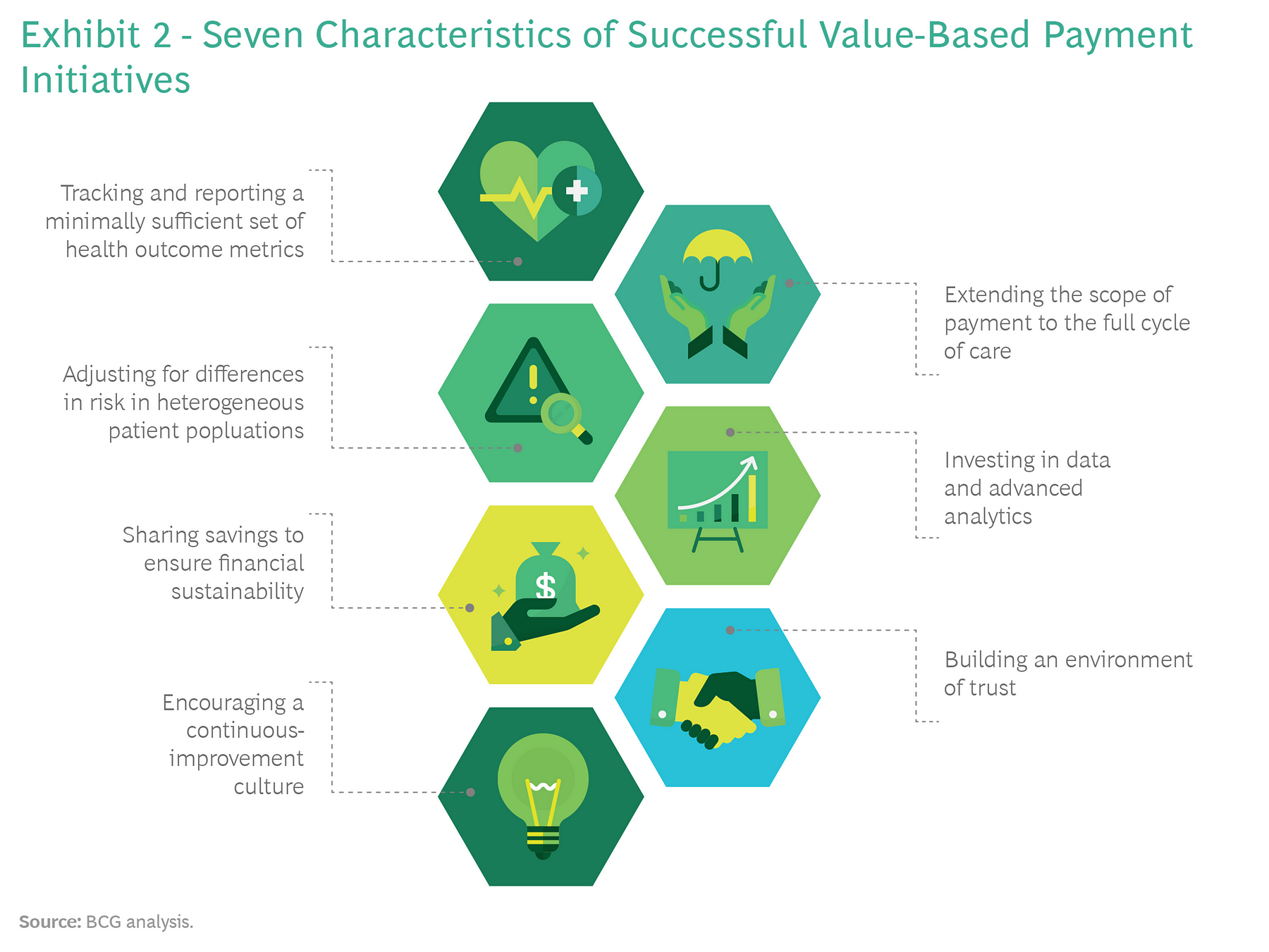

When we looked closely at these case studies, we identified seven characteristics that were common to successful value-based payment initiatives-regardless of the payment model-and that distinguished them from the rest. (See Exhibit 2.)

- 1.OUTCOMES – Tracking and Reporting a Minimally Sufficient Set of Health Outcome Metrics

- 2.VALUE BASED PAYMENT – Extending the Scope of Payment to the Full Cycle of Care

- 3.RISK ADJUSTMENT – Adjusting for Differences in Risk in Heterogeneous Patient Population

- 4.DATA & ANALYTICS – Investing in Data and Advanced Analytics

- 5.SHARED SAVINGS – Sharing Savings to Ensure Financial Sustainability

- 6.TRUST – Building an Environment of Trust

- 7.CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT – Encouraging a Continuous-Improvement Culture

1.OUTCOMES – Tracking and Reporting a Minimally Sufficient Set of Health Outcome Metrics

Value-based health care is all about delivering better health outcomes for the same, or a lower, cost. Therefore, measuring and reporting the health outcomes that matter to patients is a prerequisite for achieving sustainable value-based payment reform.

The most successful initiatives that we studied supplement their traditional metrics-such as adherence to process standards and compliance with treatment guidelines-with metrics that reflect the health outcomes delivered to patients. Indeed, some of the most successful initiatives include financial incentives for providers to report outcomes; others mandate reporting outcomes as part of a national health policy.

When tracking health outcomes, it’s important to strike the right balance between too many metrics and too few. Too many, and the metrics will provide weak signals that have minimal impact on provider behavior; too few, and they risk missing relevant outcomes.

Consider the example of prostate cancer. If a health system tracks only long-term mortality (say, five-year survival rates), then the system is likely to miss large variations in outcomes that matter to patients-for instance, whether or not they suffer from incontinence or severe erectile dysfunction a year after surgery.

Organizations such as the International Consortium of Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) have made significant progress in defining minimally sufficient sets of the relevant health outcomes for specific diseases and conditions.15 Notes: 15 ICHOM has assembled international working groups of clinicians and patient representatives that have agreed on minimally sufficient standard sets for the relevant outcomes to track 28 common medical conditions. For more information, see www.ichom.org.

2.Extending the Scope of Payment to the Full Cycle of Care

For many of the initiatives we studied, the effort to improve health care value failed because value-based payments were limited to only a subset of the care required to achieve desired patient outcomes. In such situations, the payment model did not create incentives for providers to innovate across the full chain of care delivery or manage the total cost of care.

By contrast, successful initiatives extended the scope of value-based payments to the full cycle of care (for example, expanding payments to include diagnostics, surgery, and physical therapy), so that providers have an incentive to share information, cooperate with one another to redesign care pathways, and provide the highest-quality care in the most cost-effective manner.

3.Adjusting for Differences in Risk in Heterogeneous Patient Populations

One of the unintended consequences that designers of value-based payment models need to guard against is inadvertantly creating incentives that encourage providers to cherry-pick only the healthiest patients. Effective value-based payment systems include robust risk adjustment in order to account for patient mix, eliminate adverse selection, and set prices that are fair to all providers, including those managing the most complex and expensive-to-treat cases.

Although risk adjustment has historically been prohibitively complex, it is now more accurate and easier to implement, given the advances in computing power, the increasing availability of large data sets, and improvements in predictive analytics.

4.Investing in Data and Advanced Analytics

To meet the growing need for more comprehensive tracking of outcomes and costs, to have value-based payments cover the full cycle of care, and to implement multiple types of payments at scale, successful initiatives develop advanced-analytics platforms. These platforms integrate data from several sources and continuously feed information to all stakeholders on how they are performing on value. Typically, individual providers do not have either the data or the analytics capabilities to develop such systems on their own. In contrast, because payers have visibility across the entire system, they are usually better positioned to develop the data and analytics platform and then provide it as a shared service to providers. Sweden’s SVEUS program, which provides comprehensive and nearly real-time data with sophisticated risk management, is one example of how these analytics platforms are developing.

5.Sharing Savings to Ensure Financial Sustainability

Another pattern we observed is that, too often, value-based payment models are implemented by payers as a means to reduce costs in the face of immediate budget pressure. Not enough attention is given to the long-term financial sustainability of the programs. Providers may share in the savings in the short term, but those near-term savings then become the justification for budget reductions in subsequent years. When this happens, it is difficult for providers to see a long-term path to success. For example, a chief criticism of the ACO model in the US is that since the cost benchmarks are based on the previous year’s spending, any savings an ACO achieves are immediately factored in to the subsequent year’s benchmark.

An alternative approach was recently announced for the Blue Premier program, a collaboration of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina (the largest payer in the state) and five major provider systems.

Blue Premier has built in mechanisms that protect long-term financial sustainability by ensuring that providers are not penalized in subsequent years for cost improvements in previous years.17 Notes: 17 See J.P. Sharp, et al., “ Engineering a Rapid Shift to Value-Based Payment in North Carolina: Goals and Challenges for a Commercial ACO Program,” NEMJ Catalyst, January 23, 2019.

6.Building an Environment of Trust

In order for value-based payment models to drive changes in clinical practice, they need to be introduced in an environment of trust among providers, payers, and patients.

That may sound like a tall order given the long history of adversarial relations between payers and providers due to the misaligned incentives of fee-for-service reimbursement models. Still, health systems can take a number of steps to build that trust and ensure sufficient buy-in for value-based payment reform.

For example, payers can make clear that the focus of initiatives is not just cost containment but also improvement in outcomes. And providers should be heavily involved in the design, implementation, and refinement of payment models, including defining outcomes and reviewing performance bonus criteria.

Furthermore, shadow budgets can be employed for a predefined period of time before the implementation of a new payment model to gather feedback, optimize the approach to risk adjustment and claims management, and increase confidence in and understanding of the payment model to ensure a smooth transition.

7.Encouraging a Continuous-Improvement Culture

Finally, successful health systems recognize that implementing value-based payments is not a one-time event. Rather, it is part of an ongoing transformation of clinical practice.

The successful implementation of value-based payments benefits from a learning mindset in which organizations commit to experimentation, innovation, and continuous improvement over time.

Indeed, in some situations, it may even involve eliminating value-based payments when the norms and practices of a genuinely value-based organizational culture are firmly entrenched. (For an example, see the sidebar “Why Geisinger Got Rid of Its Value-Based Bonus.”)

Originally published at https://www.bcg.com on January 8, 2021.

To download the PDF of the full version of the report, open the URL below:

http://image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-Paying-for-Value-in-Health-Care-September-2019_tcm9-227552.pdf