This is a republication of the article below, with the title above. The second part of this post, contains a “rapid response” just published at the BMJ.

England going smoke-free by 2030 depends on No 10 willpower

The Guardian

Andrew Gregory Health editor

June 8, 2022

cityam

Key messages

by Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Health Revolution

Institute for Health Strategy and Digital Health

June 9, 2022

3 billion people globally still use tobacco products.

- They kill 8 million people every year, and

- more than one million of whom die from exposure to second-hand smoke.

In an effort to finally stamp out its use, and eradicate its associated harms, many western countries have announced bold tobacco policies with the aim of going smoke-free before the end of this decade. Some are going further and faster than others.

New Zealand is one of those leading the race after it announced it will outlaw smoking for the next generation, so that those who aged 14 and under today will never be legally able to buy tobacco.

- The legislation means the legal smoking age will increase every year, to create a smoke-free generation of New Zealanders.

- Other measures aimed at reaching its goal of making the country smoke-free by 2025 include:

- reducing the legal amount of nicotine in tobacco products to very low levels;

- reducing the number of shops where cigarettes can legally be sold; and

- increasing funding to addiction services.

In England, health officials are considering radical ways to reduce the number of smokers from the estimated total of 6 million.

The question is not what is in the Khan review but whether its recommendations will be implement

England going smoke-free by 2030 depends on No 10 willpower

The Guardian

Andrew Gregory Health editor

June 8, 2022

While much has been made recently of the danger posed by soaring obesity levels, tobacco remains the biggest public health threat the world has ever faced.

Despite its risks being known for decades, 1.3 billion people globally still use tobacco products. They kill 8 million people every year, and more than one million of whom die from exposure to second-hand smoke.

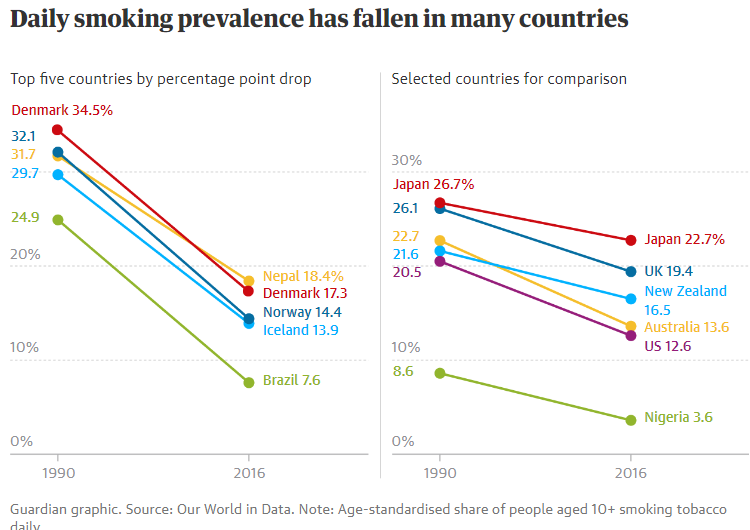

In an effort to finally stamp out its use, and eradicate its associated harms, many western countries have announced bold tobacco policies with the aim of going smoke-free before the end of this decade. Some are going further and faster than others.

… many western countries have announced bold tobacco policies with the aim of going smoke-free before the end of this decade. Some are going further and faster than others.

New Zealand

New Zealand is one of those leading the race after it announced it will outlaw smoking for the next generation, so that those who aged 14 and under today will never be legally able to buy tobacco.

New Zealand is one of those leading the race after it announced it will outlaw smoking for the next generation, so that those who aged 14 and under today will never be legally able to buy tobacco.

The legislation means the legal smoking age will increase every year, to create a smoke-free generation of New Zealanders.

Other measures aimed at reaching its goal of making the country smoke-free by 2025 include:

- reducing the legal amount of nicotine in tobacco products to very low levels;

- reducing the number of shops where cigarettes can legally be sold; and

- increasing funding to addiction services.

England

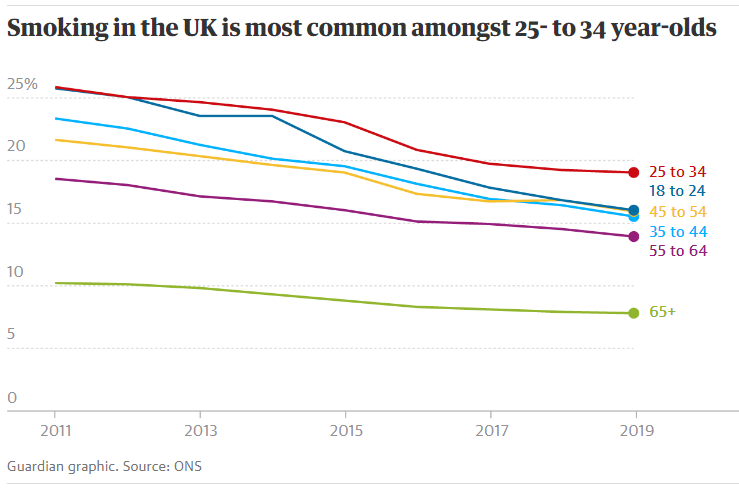

In England, health officials are considering radical ways to reduce the number of smokers from the estimated total of 6 million.

On Thursday, an independent review commissioned by the health secretary, Sajid Javid, and led by Javed Khan, a former chief executive of the children’s charity Barnardo’s, will be published.

In England, health officials are considering radical ways to reduce the number of smokers from the estimated total of 6 million.

The Guardian understands the recommendations could include

- raising the legal age of smoking to 21 and

- introducing further taxes on tobacco companies.

The review is also likely to recommend the NHS increase efforts to encourage smokers, particularly among pregnant women, to switch to vaping and e-cigarettes.

The minimum age for tobacco purchases was last raised from 16 to 18 in England, Scotland and Wales in 2007.

Smoking in enclosed public spaces and workplaces was made illegal in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in the same year.

Scotland brought in legislation in 2006.

The Khan review into smoking was commissioned to provide independent, evidence-based advice to the government to help reduce inequalities linked to smoking.

Khan was also tasked with identifying the “most impactful interventions” to cut uptake of smoking and support people quitting.

The government announced in 2019 its ambition to go smoke-free in England by 2030.

Some sources have suggested the review, which was commissioned in February, is “political cover” for Javid to prevent the risk of Downing Street ditching the 2030 target, amid fears the Conservatives may be accused of trying to implement a “nanny state”.

David Canzini, the influential deputy chief of staff in No 10, has advised Boris Johnson to scrap as many policies as possible that may be unpopular with Tory MPs or traditional Conservative voters.

The Conservatives will also be keen not to lose the ground made with red wall voters, something they may fear would be at risk if tight tobacco policies are suddenly thrust on them.

Javid, who quit smoking after becoming health secretary last year, is understood to be in favour of significant changes to the government’s tobacco policy.

He is said to have examined policies in the US, where the legal age is 21, as well as countries such as New Zealand, and considered tightening rules on sales.

But there is scepticism among other members of the cabinet and Johnson about raising the legal age, or introducing new taxes.

Cancer Research has previously warned that England is expected to miss its target of being smoke-free by 2030 because so many poorer people are still using cigarettes.

Whether or not England can hit the target will depend not on the size or shape of the policies recommended on Thursday, but on whether the government is prepared to implement them.

The question is not what is in the Khan review but whether its recommendations will be implement

Originally published at https://www.theguardian.com on June 8, 2022.

Names mentioned

health secretary, Sajid Javid

Javed Khan, a former chief executive of the children’s charity Barnardo’s

RELATED PUBLICATION

Legal smoking age in England should rise every year, review recommends

BMJ 2022; 377

doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o1432

(Published 09 June 2022)Cite this as: BMJ 2022;377:o1432

Rapid Response:

The Javed Khan review — time to make smoking obsolete

Dear Editor

We welcome the publication of Javed Khan’s Independent Review into smoking and urge the Government to heed his call for immediate investment of £125 million in tobacco control to deliver its Smokefree 2030 ambition [1].

Up to two thirds of smokers die prematurely, losing on average 10 years of life [2].

Achieving the Smokefree 2030 ambition[3] of adult smoking rates of 5% or less, would at a stroke deliver the Levelling Up mission to extend healthy life expectancy by 5 years [4].

Targeted investment to tackle inequalities in smoking rates across society is desperately needed.

Smoking is a far greater source of difference in life expectancy than socio-economic status, and these differences can only be eliminated if we achieve the Government’s goal of making smoking obsolete [5].

We agree with the Secretary of State for Health, that it is a “moral outrage” [6] that England’s richest people live on average up to a decade longer than the poorest.

It is time for the Government to match words with deeds, outrage with action.

That’s what the public wants too, with a substantial majority supporting a range of Government interventions, and only 6% thinking the Government is doing too much [7].

No time is to be lost, if current trends continue we will miss the target by 7 years, and around double that for the poorest communities [8].

Ministers have recognised the need to “floor it” on public health [9], but that requires fuel in the tank.

The Tobacco Control budget has been cut by a third in real terms since 2015 [10], and additional investment is desperately needed, alongside tougher regulation.

If the Government cannot find the necessary funding, then, as Khan says, it should ‘make the polluter pay’.

If the Government cannot find the necessary funding, then, as Khan says, it should ‘make the polluter pay’.

This was also the recommendation of the APPG on Smoking and Health, which urged the Government to strictly control the profitability of the tobacco transnationals [11].

Reducing net profit margins from around 50% to no more than 10%, in line with the average for other businesses[12], could release £700 million excess profits a year [13] which should be used to fund tobacco control and other Levelling Up measures.

Reducing net profit margins from around 50% to no more than 10%, in line with the average for other businesses[12], could release £700 million excess profits a year [13] which should be used to fund tobacco control and other Levelling Up measures.

Smoking is not a lifestyle choice, it is an addiction usually starting in childhood.

Stopping smoking benefits hard-pressed families, reducing poverty by increasing disposable household income; creating jobs; increasing productivity; reducing NHS waiting lists; and improving health and wellbeing.

The £12 billion a year spent on tobacco [14] has greatest impact on poorer communities where smoking rates are highest, exacerbating the cost of living crisis.

In addition to the £2.4 billion smoking costs the NHS; and £1.2 billion for social care; a further £13 billion accrues from lost productivity due to premature death, disease and disability [14].

In addition to the £2.4 billion smoking costs the NHS; and £1.2 billion for social care; a further £13 billion accrues from lost productivity due to premature death, disease and disability [14].

The Government rightly wants to make smoking obsolete [3].

If this were achieved, it is estimated that UK jobs would increase by 500,000 as smokers spent their money on other goods and services [15].

The net benefit to public finances would be around £600 million for England alone [15].

Nationally around 14% of adults smoke but rates in social housing, where a third of smokers live, are double that [16].

Around 25% of people with depression and anxiety [17] and over 40% of those with severe mental illness smoke[18].

Smoking is the single biggest modifiable risk factor for cancer [19] and COPD, as well as for miscarriages, stillbirth, premature birth and birth anomalies [20].

Women in the most deprived group are five times more likely to smoke in pregnancy than the least deprived.

Around 25% of people with depression and anxiety [17] and over 40% of those with severe mental illness smoke[18].

Smoking is the single biggest modifiable risk factor for cancer [19] and COPD, as well as for miscarriages, stillbirth, premature birth and birth anomalies

Every day the Government fails to act more than 200 people in England die from smoking [21] and 280 children under 16 have their first cigarette [22].

Two thirds of those smoking one cigarette will go on to become addicted, daily smokers[ 23], taking on average thirty attempts before they successfully quit [24].

The Health Disparities White Paper is due shortly, a fully-funded comprehensive Tobacco Control Plan to make smoking obsolete must follow swiftly on its heels.

The Health Disparities White Paper is due shortly, a fully-funded comprehensive Tobacco Control Plan to make smoking obsolete must follow swiftly on its heels.

Nicholas S. Hopkinson, chair, Action on Smoking and Health

Helen Stokes-Lampard, chair, Academy of Medical Royal Colleges

Jim McManus, president, Association of Directors of Public Health UK

Sarah Woolnough, chief executive, Asthma+Lung UK

Charmaine Griffiths, chief executive, British Heart Foundation

David Strain, chair, BMA Board of Science

Ian Walker, executive director, Cancer Research UK

Maggie Rae, president, Faculty of Public Health

Jennifer Dixon, chief executive, The Health Foundation

Gill Walton, chief executive, Royal College of Midwives

Eddie Morris, president, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Andrew Goddard, president, Royal College of Physicians

Adrian James, president, Royal College of Psychiatrists

Linda Bauld, director, SPECTRUM

Pat Cullen, general secretary & chief executive, Royal College of Nursing

Martin Marshall, president, Royal College of General Practitioners

Carol Black, chair, Centre for Ageing Better

References

See the original publication

Originally published at https://www.bmj.com

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

The Khan review

Making smoking obsolete

Independent review into smokefree 2030 policies

Dr Javed Khan OBE

Published 9 June 2022