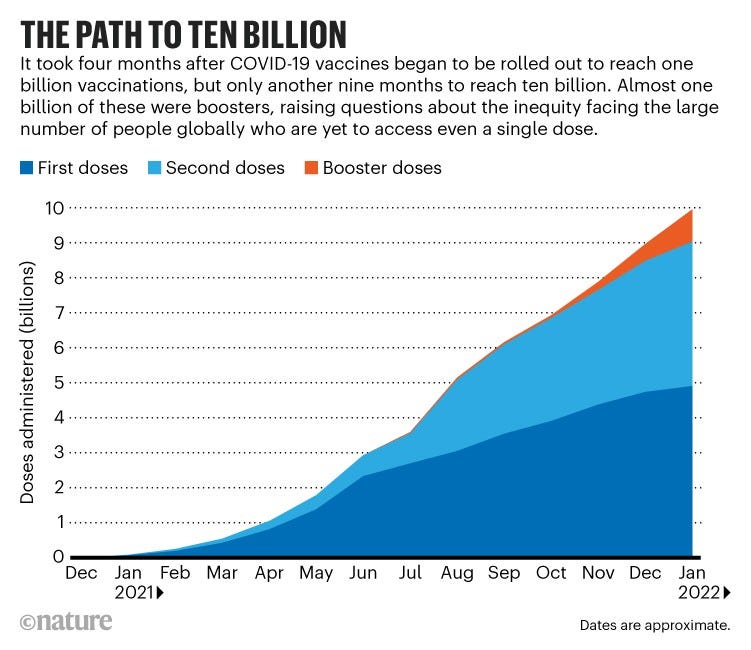

More than ten billion doses have gone into arms in a remarkably short period of time — but scientists warn that woeful inequities in access remain.

4.8 billion people — have received at least one dose of one of more than 20 different COVID-19 vaccines that have been approved by nations for use around the world.

But — as researchers warned last year when the first one billion doses had been administered — there are still huge inequities in access, with just 5.5% of people in low-income nations having received two doses.

Nature

Freda Kreier

January 31, 2020

More than ten billion doses have gone into arms in a remarkably short period of time — but scientists warn that woeful inequities in access remain.

In little more than a year, ten billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been administered globally, in what has become the largest vaccination programme in history.

Many nations began rolling out vaccines in late 2020 and early 2021, and since then more than 60% of the world’s population — 4.8 billion people — have received at least one dose of one of more than 20 different COVID-19 vaccines that have been approved by nations for use around the world.

“The world has never seen such rapid scale-up of a new life-saving technology,” says Amanda Glassman, executive vice-president of the Center for Global Development in Washington DC. “The effort under way is inspiring.”

“The world has never seen such rapid scale-up of a new life-saving technology,

But — as researchers warned last year when the first one billion doses had been administered — there are still huge inequities in access, with just 5.5% of people in low-income nations having received two doses.

‘Extreme inequity’

By contrast, many of the world’s high- and middle-income nations are now pushing ahead with progammes to deliver third, or even fourth doses (see ‘The path to ten billion’), with these boosters currently making up around one-third of all COVID-19 vaccine doses administered each day worldwide.

Some scientists caution that this continued inequity increases the risk of new SARS-CoV-2 variants emerging from poorly vaccinated populations.

“As an African, the real significance of reaching ten billion vaccines administered is the extreme inequity that exists in vaccine distribution between the global north and global south,” says Mosoka Fallah, founder of Refuge Place International, a public-health organization headquartered in Bassa Town, Liberia. “Until we correct this inequity, the world will continue to see new variants.”

Some scientists caution that this continued inequity increases the risk of new SARS-CoV-2 variants emerging from poorly vaccinated populations.

At present, just 16% of people across the entire African continent have received even one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Wealthy nations have been donating surplus vaccine doses to low-income nations, but Fallah says that if patents were to be waived on existing vaccines — an issue that is currently the subject of debate at the World Trade Organization in Geneva, Switzerland — it would allow more countries to make their own vaccines, increasing supply.

… if patents were to be waived on existing vaccines … it would allow more countries to make their own vaccines, increasing supply.

Despite these issues and the challenges with distribution, reaching the milestone of ten billion doses “is an unprecedented global moment,” says Soumya Swaminathan, chief scientist of the World Health Organization, based in Geneva.

“It is a huge scientific achievement that ten billion doses of vaccines to a new pathogen were developed in two years from its identification.”

Despite these issues and the challenges with distribution, reaching the milestone of ten billion doses “is an unprecedented global moment …

“It is a huge scientific achievement that ten billion doses of vaccines to a new pathogen were developed in two years from its identification.”

Originally published at https://www.nature.com.

Names mentioned

Amanda Glassman, executive vice-president of the Center for Global Development in Washington DC.

Mosoka Fallah, founder of Refuge Place International

Soumya Swaminathan, chief scientist of the World Health Organization,