This is an excerpt of the publication above, focusing on the overview of the project.

IDB and Healthcare Israel

Amir Gilboa and Luis Tejerina

2022

Edited by

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

The Health Revolution Institute

Research Institute for “Better Health and Care for All, at a lower cost”

June 15, 2022

Structure of the publication

- Preface

- Executive Summary

- Background

- Introduction

- The Need for the HIE, and the Challenges it Addresses

- The Israeli National HIE Solution

- The Israeli National HIE Implementation

- Evaluation of Results

- Reflections and Recommendations

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Health Information Exchange (HIE) is one of the main national digital health infrastructures of Israel’s digital health strategy, which is led by the MOH.

From the early stages of the HIE’s planning, the MOH emphasized the importance of not only technology but also the health system’s structure and budget constraints to generate higher HIE usage rates and, therefore, better results for patients.

When the HIE was conceptualized, most Israeli health organizations used electronic medical records (EMRs).

This situation had three main limitations:

(1) a patient’s complete medical history was not available to all caregivers and providers, as EMRs contained only an individual organization’s data,

(2) the absence of patients’ complete medical histories led to providers requesting unnecessary tests and procedures, and

(3) the absence of complete medical histories also meant that medical teams providing emergency care did not have access to life-saving information about the correct course of treatment for patients needing specialized care.

Moreover, the incorporation of EMRs into an HIE involves technical, terminology- and security-related challenges.

For example, different organizations may use different names for the same diagnosis or procedure, but it is important that all organizations using the HIE speak the same “language” if an HIE is going to function.

Also, privacy and security issues must be considered to be sure that medical information is shared in only the most secure way that prevents private patient data from reaching the wrong hands.

Israel’s first implemented an HIE, called Ofek, in the hospitals of Clalit Health Systems, which is Israel’s largest health maintenance organization (HMO), and then expanded it to community care providers and, ultimately, national use.

Ofek contained a minimal dataset that was decided on by Clalit’s physicians and medical teams in its hospitals and community clinics in an effort to make the HIE more accurate and efficient.

Using the lessons learned from Ofek’s structure and implementation, which revealed gaps and missing data, Israel’s second HIE version — Eitan — was developed with expanded capabilities and data.

Using the lessons learned from Ofek’s structure and implementation, which revealed gaps and missing data, Israel’s second HIE version — Eitan — was developed with expanded capabilities and data.

The Eitan implementation was challenging and included very close collaboration with all stakeholders.

But stakeholders’ understanding of the HIE’s importance has been the main reason that all health organizations in Israel now use it as part of their day-to-day work.

To help organizations meet the costs of implementing the HIE, the MOH offered a financing incentives program.

Since the implementation, clear improvements in the measurements that affect health organizations and each patient in Israel are visible.

To help organizations meet the costs of implementing the HIE, the MOH offered a financing incentives program.

The HIE’s architecture accounts for organizational concerns about data ownership, privacy and security, and, of course, the Israeli healthcare system’s structure.

Furthermore, Israel has invested in addressing problems with differing terminologies within partnering systems to ensure fluent, smooth operations at each point of care.

Following the success of the nationwide HIE design, build, and implementation, work continues on monitoring and improving the platform, including adding new capabilities.

The MOH’s plan for the future of the HIE contains new developments and features, and that plan is revised each time the MOH updates the national digital health strategy, that is updated from time to time according to the developments in the field.

PREFACE

Healthcare Israel as part of The Israeli Healthcare System

Healthcare Israel (HCI) is a government agency created by Israel’s Ministry of Health (MOH) in 2016 to deliver lifesaving and cost-saving healthcare innovations, technology, and expertise to the world — government to government (G2G).

Its mission is to promote broad and long-standing cooperation between the MOH and partner governments and increase health system exports through tri-sectoral collaborations between governments, health systems, and the healthcare industry to make the world a healthier place.

Healthcare Israel (HCI) is a government agency created by Israel’s Ministry of Health (MOH) in 2016 to deliver lifesaving and cost-saving healthcare innovations, technology, and expertise to the world — government to government (G2G).

HCI is a public agency with a start-up’s soul.

It brings life-saving Israeli healthcare technology and innovation together with the policies and regulations required to move them forward; the training, systems, and expertise needed to implement them; and the foreign governments that have the desire and resources to acquire them.

HCI also brings Israeli private sector healthcare leaders and public health organizations under the government’s umbrella to shorten the tendering process, facilitate multilayered partnerships, and deliver unique G2G solutions.

Given Israel’s small size, many of the international governments and countries that HCI works with are much larger geographically, with much bigger populations and far bigger national budgets.

Israel has created a world-class healthcare system: it has a 90 percent patient satisfaction rate at home, top-tier rankings by international health measures, one of the world’s lowest costs per patient, and a world-class community and primary care system.

Israel has created a world-class healthcare system: it has a 90 percent patient satisfaction rate at home, top-tier rankings by international health measures, one of the world’s lowest costs per patient, and a world-class community and primary care system.

The country has also become a leading developer and exporter of life-saving healthcare technology, training, systems, policies, medical equipment, and expertise.

Hagai Dror

Managing Director at Healthcare Israel

1.BACKGROUND

The Israeli HIE model is deeply rooted in the country’s healthcare system. To understand the importance and success of the HIE, it is necessary to understand its evolution into its current structure. This knowledge will help countries adopting the HIE understand the steps involved in bringing the HIE to a national scale.

1.1 The Israeli Healthcare System

Israel has created a world-class healthcare system. All healthcare services are provided by HMOs (officially called “health funds”), which have about a 90 percent patient satisfaction rate (Myers-JDC-Brookdale, 2020)[1], top-tier rankings according to international health indicators, and impressive treatment statistics — Israel’s life expectancy is among the highest worldwide.

The highly developed primary care system has also been praised by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as “excellent” (OECD, 2012)[2].

Israel also led the world in introducing open access to COVID-19 vaccines for every citizen.

The following Israeli health indicators are from OECD Data (2021):[3]

· Life expectancy: 82.8 years (Men 80.7, Women 84.8) (2020)

· Infant mortality: 3.1/1,000 live births (2019)

· Years of potential life lost: 3,175/100,000 inhabitants (2018)

· % of daily smokers: 16.4 percent (2019)

· Overweight or obese: 56 percent (2020)

1.1.1. Organization

The National Health Insurance Law ensures each resident access to universal healthcare that includes a comprehensive basket of health services regardless of a patient’s gender, religion, age, location, ethnic background, income, or current state of health.

The MOH is responsible for the health system’s policy setting, regulation, budgeting, planning, and control, and it runs the public health services.

The provision of health services is delegated to four not-for-profit HMO-like organizations (Ministry of Health, n.d.a.)[4].

Each Israeli resident is registered in one of the four and can readily move between them, regardless of the individual’s medical conditions or income level.

The HMOs provide two types of medical services — primary care services and community services — that are determined by the National Health Insurance Law and are updated yearly.

Primary care services and ambulatory specialist care are provided and financed by the HMOs in a community.

Primary care is usually delivered by family medicine specialists, primary internists, and gynecologists, and according to Rosen (2011)[5], the services are readily accessible.

Community services include primary care physicians, specialists, other community-based services, and emergency centers that operate 24/7, which relieves the burden on hospitals’ emergency rooms.

Primary care services and ambulatory specialist care are provided and financed by the HMOs in a community.

Primary care is usually delivered by family medicine specialists, primary internists, and gynecologists, and … the services are readily accessible.

Community services include primary care physicians, specialists, other community-based services, and emergency centers that operate 24/7, which relieves the burden on hospitals’ emergency rooms.

Most general hospitals are non-private and owned by the MOH, HMOs, or other NGOs.

The clinical quality of the general hospitals in Israel and their facilities are very good.

One Israeli hospital has been selected by the magazine Newsweek as one of the world’s 10 best hospitals of 2021 (Newsweek, 2021)[6].

There are a few private general hospitals that, as of 2021, make up about 3 percent of Israel’s total number of hospital beds (Ministry of Health, 2021)[7].

The rehabilitation, geriatric, and psychiatric hospitals are owned by public or private organizations and accept mostly public patients.

1.1.2. Financing

The healthcare system is financed primarily through a combination of general taxes and health-specific payroll taxes.

The taxes are collected by the government, which then pools the resources and allocates them to the HMOs according to a capitation formula.

The formula considers the number of patients in each HMO and the patients’ age mix, gender, and place of residence to distribute health resources adequately, fairly, and efficiently.

The health payroll tax is usually 5 percent of the individual’s income, with a discount for low-income families.

Citizens pay small co-payments for ambulatory services and prescription drugs, and there is a cap on co-payments for heavy users of services and medications (Commonwealth Fund 2020)[8].

The health payroll tax is usually 5 percent of the individual’s income, with a discount for low-income families.

Hospitals are financed through the services they supply to the public, which are paid for by the HMOs and some government subsidies.

Some NGO-owned hospitals (which are not part of HMOs) are allowed to accept private patients.

1.1.3. Quality Measurement

Israel measures how well its healthcare system serves patients and publicly publishes quality measurements, (Ministry of Health, 2019)[9] service indicators (such as waiting times), and patient satisfaction rates (Ministry of Health, 2019)[10].

Patient satisfaction across all HMOs is regularly monitored and averages around 90 percent. (Myers-JDC-Brookdale, 2020)[11]

Primary care is periodically assessed through national quality indicators, and the results are transparent to the public.

The OECD observed that “Israel’s primary care services focus on preventive care and patient follow-ups based on extensive quality monitoring indicators, providing an exemplary model to other countries” (OECD, 2016)[12].

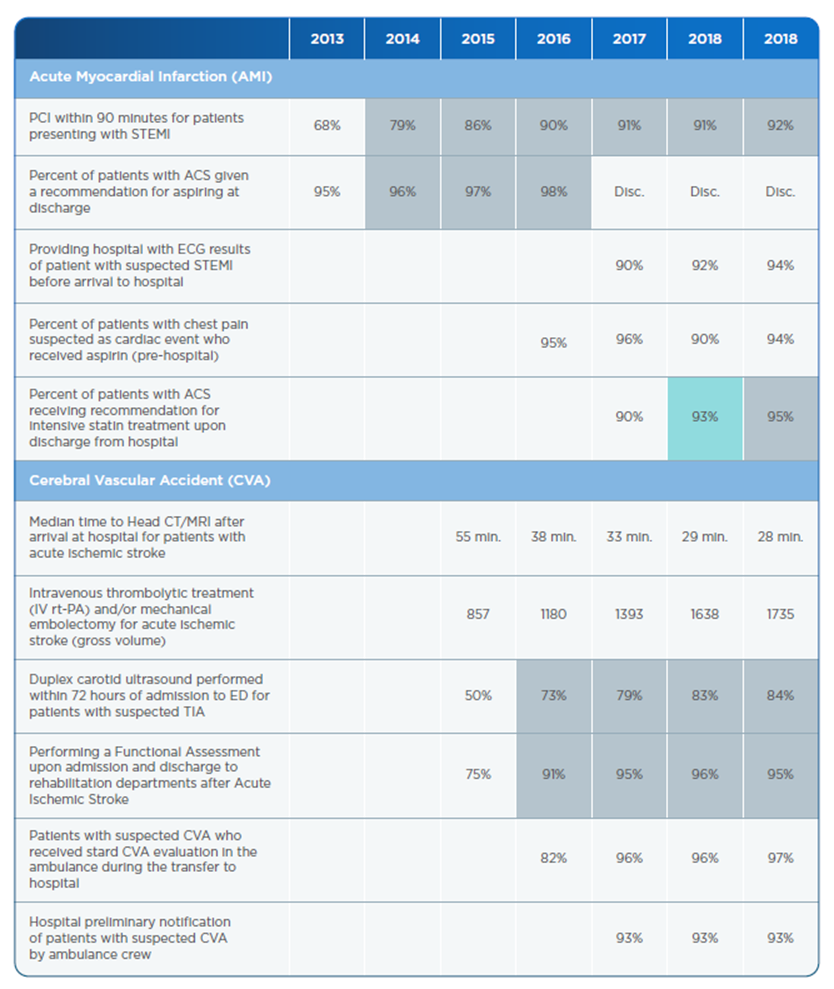

The government-designed quality indicators that hospitals use are determined yearly (Table 1), and patients and health professionals can access the quality results online to review a hospital’s ranking in relation to other organizations.

This process gives patients a voice and a choice in the quality of their healthcare and gives providers the incentive to improve.

In summary, the combination of universal care through the National Health Insurance Law, the wide package of services, strong community care, and excellent hospitals led by the MOH and the four HMOs makes the Israeli healthcare model unique in quality, cost-effectiveness, efficiency, patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, and world rankings.

In summary, the combination of universal care through the National Health Insurance Law,

the wide package of services, strong community care, and excellent hospitals led by the MOH and the four HMOs

makes the Israeli healthcare model unique in quality, cost-effectiveness, efficiency, patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, and world rankings.

TABLE 1: A Sample of Hospital Quality Indicators Program Data, 2013–2019

Source: The National Program for Quality Indicators (MOH 2020)[13].

2. INTRODUCTION

2.1 The Israeli Digital Health Strategy

To achieve Israel’s digital health transformation, the MOH built a national strategy for digital health, which was approved in 2018 through a government resolution (Ministry of Health, 2018b)[14].

The strategy’s implementation included building a core infrastructure, as designed by the ministry, to support the strategy.

To achieve Israel’s digital health transformation, the MOH built a national strategy for digital health, which was approved in 2018 through a government resolution

2.1.1. The Core Infrastructure of the Digital Health Transformation

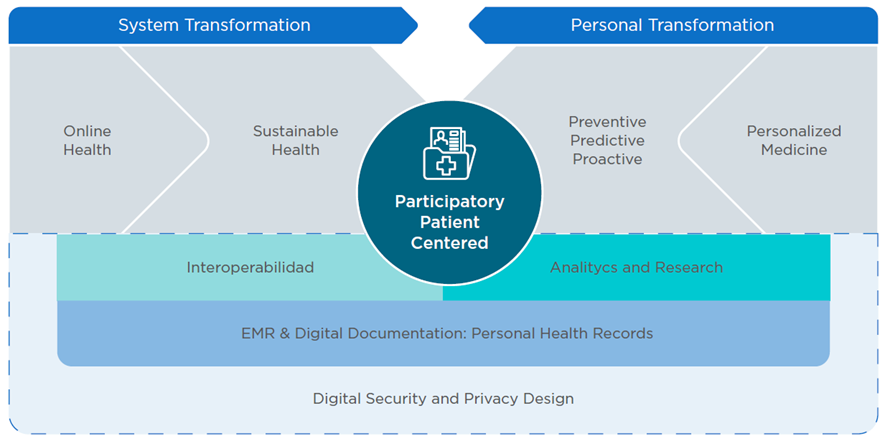

The national strategy for digital health centers on the digital health transformation.

The main goal is to achieve participatory, patient-centered health that establishes patient health as a partnership between healthcare providers and patients.

Patient-centered health includes exploring data and communication-based methods and options to empower patients to make more informed choices regarding behavior and treatment options that are suited to their condition and play a more active and participatory role in their healthcare.

This means providing patients and the public access to information that until recently was available only to health professionals.

The main goal is to achieve participatory, patient-centered health that establishes patient health as a partnership between healthcare providers and patients.

Patient-centered health includes: exploring data and communication-based methods and options to empower patients to make more informed choices regarding behavior and treatment options

that are suited to their condition and play a more active and participatory role in their healthcare.

The core transformations consist of the following four major healthcare service principles (Figure 1):

- Personalized Medicine

- Health Promotion (Preventive, Proactive, Predictive Health)

- Sustainable Health

- Online Health

Personalized Medicine is the ability to provide medical care that is tailored to the needs of individual patients.

This type of medical care presupposes two complementary components:

· Research based on Big Data that allows retrospective identification of correlation patterns between successful treatment protocols using large data aggregations

· Accessibility of the data concerning a specific patient and his/her medical history

The two components combine to make it possible to compare a single patient’s data with patterns identified across a data set or an entire population.

Access to this data prevents inappropriate diagnoses and treatments, reduces unnecessary patient suffering and negative outcomes, and enhances the effectiveness of treatment — while reducing costs (Ministry of Health, n.d.b)[15].

Health Promotion (Preventive, Proactive, and Predictive) — reflects the idea that healthcare is moving away from the artificial, binary distinction of health or sickness toward a broader concept of a spectrum of health.

At each point along this spectrum, it is possible to promote patient health, reduce the risks of specific illnesses, or delay the onset of medical crises as long as possible to improve quality of life.

The key is to use data to predict, prevent, and provide proactive medicine before patients suffer unnecessary or preventable medical crises.

Health Promotion (Preventive, Proactive, and Predictive) reflects the idea that healthcare is moving away from the artificial, binary distinction of health or sickness toward a broader concept of a spectrum of health.

Sustainable Health — is a healthcare transformation that maximizes the benefits of existing resources within a healthcare system in sustainable ways.

Examples include using telemedicine or changing work procedures in emergency rooms based on a quantitative assessment of processes and an understanding of blockages and bottlenecks.

Online Health — empowers health professionals, health providers, and patients by making digital health information available online.

As an example, the country’s insurance organizations have online sites[16] for people to access their medical records. Figure 1 shows the infrastructure that supports the four cores of digital health transformations.

2.1.2. Digital Security and Privacy by Design

The digital security and privacy layer of the national digital health strategy includes cybersecurity and privacy considerations that are taken into account as each of the above transformations is implemented.

This layer has two goals. The security goal is to ensure that the system is working as expected at all times so that core intellectual property is not infringed upon.

The privacy goal is to ensure that patient data and intellectual property are kept according to relevant standards (HIPAA [Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act], GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation], etc.).

Therefore, we incorporate privacy and security standards at all phases of system design, from the planning stage through to implementation.

While cybersecurity is an integral part of every project, some cybersecurity elements need to be addressed independently.

These elements, which mainly exist on the national level under the responsibility of the INCD and the MOH as part of the national health cyber infrastructure, include:

· Formulating and issuing guidelines and policies for managing privacy and security risks

· Implementing general IT security standards focused on cloud security, endpoint protection, DOS (denial-of-service) threats, and ransomware mitigation.

· Setting up designated sectoral C4I (command, control, communication, computers, and intelligence) capacities such as having a security operation center, gathering cyber-intelligence, monitoring organizational networks (including specialized protocols and IoT devices), distributing IOC (indicators of compromise) and sharing sectoral information, and ensuring interoperability with peer and national cyber agencies.

· Establishing situational digital awareness by having a playbook of cyber situations to be ready for.

· Offering awareness training for the general workforce and designated capacity building for cybersecurity teams on topics such as phishing attacks, secured passwords, social networks, and more.

· Using incident response (IR) teams and building their capabilities, with each organization responsible for its IR team.

FIGURE 1: Core Digital Health Transformations

Source: Internal Ministry of Health presentation.

2.1.3. Building the Digital Health Transformation’s Infrastructure

It is widely accepted that digital health transformations offer dramatic changes and great benefits to citizens, health care ecosystems, and the governments that invest billions of dollars in them.

At the core of the digital health strategy are three gradual, information-based transformations:

- Collecting medical information in EMRs and digital documentation.

- Ensuring the medical systems’ interoperability.

- Analyzing and researching health data.

The foundation for all subsequent digital health transformations is the collection of medical information in EMRs and digital documentation for every point of a patient’s care.

The clinical information is collected by EMRs and administrative information systems (ATD\ADT) at hospitals, community clinics, primary care physicians, specialist clinics, and other settings.

There is a wide spectrum of EMR and ATD systems in Israel and other countries, from small open-source solutions for doctors or specialist clinics to huge commercial solutions for hospitals networks and HMOs, so specifying the requirements and choosing the right solution is very important for a successful transformation.

Privacy and security considerations should also be put into place regarding collecting, saving, and using the data.

The second transformation is ensuring the medical information systems’ interoperability.

Interoperability has a lot to do with all relevant stakeholders in the healthcare system being able to share clinical information, but it also has to do with allowing the stakeholders to operate in seamless, continuous integration from the patient’s point of view.

This ability is crucial if medical systems are to achieve continuity of care and give doctors a full picture when treating a patient.

Health systems’ interoperability requires the use of solutions like the HIE platform.

The HIE implementation can be at the city, region, state, or country level.

The third transformation — analyzing and researching health data — involves analyzing relevant information for data-driven decision-making …

… while making long-term decisions based on trends or ad hoc decisions based on online data and when researching the data to develop new treatments, protocols, medications, and the like based on Big Data tools.

Those analytics and research platforms can support doctors in decision-making and support policy design through the vast array of available information-based tools (artificial intelligence, decision support systems).

In Israel, the MOH published widespread regulations regarding the use of medical data, with emphasis on the secondary use of data (Ministry of Health, 2018a)[17].

Any clinical research involving personal data is subjected to prior approval by a Helsinki Committee that guarantees patient consent and understanding of the nature and risks of the study.

Israel’s HIE does not allow interorganizational clinical research across its platform.

2.2. The Role of the HIE in National Digital Health Architecture

The interoperability of medical information systems is what makes Israel’s digital health strategy work.

As mentioned above, the foundation of medical information systems is the proper digital collection of medical information.

The foundation for interoperability is the national HIE, which is why it is a fundamental part of the nation’s healthcare architecture.

The HIE enables all stakeholders in the Israeli health system to access necessary medical information when and where it is needed to serve patients.

The HIE enables all stakeholders in the Israeli health system to access necessary medical information when and where it is needed to serve patients.

Just as public transportation and roads allow people to travel throughout a country, a modern healthcare system should provide digital infrastructure for patients’ medical information to travel along with them.

On the roads, all drivers are tested and licensed, and in the digital realm, all HIE operators must meet strict regulatory requirements.

The Israeli digital health strategy sees the HIE as the first step toward a properly functioning digital health system.

Once the HIE platform is in place, advanced services can be added, including data collection for researchers and smart algorithms to support decision-makers.

Even without adding advanced services, the Israeli experience shows the value that comes from sharing medical information through the HIE.

Once the HIE platform is in place, advanced services can be added, including data collection for researchers and smart algorithms to support decision-makers.

Even without adding advanced services, the Israeli experience shows the value that comes from sharing medical information through the HIE.

References

See the original publication

About the authors

Written by: Amir Gilboa.

Technical edition: Luis Tejerina.

The author wishes to thank the following people for their contributions and remarks:

• Hagai Dror — Managing Director, Healthcare Israel

• Dr. Izhak Zaidise — Chief Medical Officer, Healthcare Israel

• Mrs. Mali Shapira — HIE Division Manager, IT Department, Israeli MOH

• Tziel Ohayon — Sr. Sales Engineer, PH Solutions Architects, DB Motion — All Scripts

Originally published at https://publications.iadb.org