BCG – Boston Consulting Group

By Ben Horner, Wouter van Leeuwen, Maggie Larkin, Julia Baker, and Stefan Larsson

SEPTEMBER 03, 2019

This is an excerpt from the report “Paying for Value in Health Care” published in September 2019, based on the chapter: “Varieties of Value-Based Payment, edited by Joaquim Cardoso.

(VBHC: Value Based Health Care)

Varieties of Value-Based Payment

Most health care providers want to do the best for their patients. But, too often, traditional activity-based payment models create disincentives to engage in the kind of clinical behaviors that improve health care value.

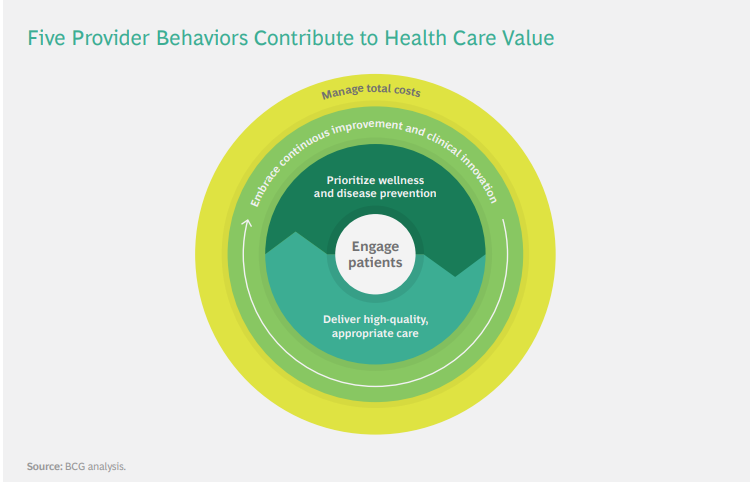

The purpose of value-based payment is to eliminate these obstacles and create financial incentives to encourage provider behaviors that improve the value delivered to patients. (See the sidebar “Five Provider Behaviors That Boost Health Care Value.”)

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

In the past, most health systems have relied on a typical division of labor. Payers were responsible for managing the costs to health systems, while providers were responsible for the quality of care delivered to patients (although often lacking the information to effectively measure it).

A core principle of value-based health care is that payers and providers should share accountability for and jointly manage costs and quality.

Payers have a key role to play because they have visibility across health systems and, therefore, are well positioned to monitor outcomes and costs for full cycles of care. However, providers are on the frontline of care delivery making the day-to-day decisions that affect patient care.

Therefore, they are in the best position not only to make informed tradeoffs about how best to deliver quality care in the most cost-effective way but also to innovate clinically to transcend those tradeoffs and deliver the same or better quality at a lower cost.

Three value-based payment models help create incentives for providers to achieve these goals:

- Pay-for-performance bonuses,

- bundled payments, and

- population-based payments.

1.Pay-for-Performance Bonuses

The simplest form of value-based payment is to pay a bonus to providers when they achieve a predetermined performance goal-for example, when they meet a defined threshold for quality care, effectively manage costs, follow clinical guidelines, or track and report health outcomes.

Bonuses can be used to introduce a value-based component to a traditional fee-for-service payment system.

They can be used in combination with other value-based payment models. They can be designed as a pure upside incentive to base compensation in order to limit provider risk, or some portion of that base compensation can be put at risk if providers do not achieve their performance targets.

The early results have been mixed.

ACOs that participate in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) of the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) typically outperform non-ACO providers on the quality measures tracked by CMS.[8]

And in 2017 (the most recent year for which data is available), 60% of the Medicare ACOs achieved savings relative to their historical benchmarks, with 34% saving enough to trigger shared-savings bonuses.9

However, the total cost savings generated by MSSP since its inception have been quite modest.

In fact, the program did not break even until 2017.

This was because the vast majority of ACO shared-savings contracts (roughly 92%) were established as upside only.

As a result, the total costs to Medicare (the combination of increased spending at ACOs that did not meet their benchmarks and the cost of shared-savings payments to those that did) have, until recently, been greater than the total savings generated.

Of course, this may change as ACOs gain experience at optimizing quality and costs and as CMS transitions ACOs to a two-sided risk model in which providers could lose money if they do not meet predefined cost and quality benchmarks.

The jury is still out as to whether the ACO model, developed in the context of the US health insurance system, is relevant to other national health systems.10

Some other countries have taken a simpler approach to using bonuses to reward providers for effectively managing the quality and total cost of care for their populations.

In Switzerland, for example, provider networks are given a relatively modest performance bonus without assuming financial risk. This policy has reduced total system costs by 17% while maintaining established quality standards. (See the sidebar “Using a Bonus to Manage Total Cost and Quality: The Swiss General-Practitioner Networks.”)

_________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

2.Bundled Payments

Another model that health systems are implementing to shift the focus to health care value is to establish a comprehensive fee for a clearly defined episode of care, rather than paying providers for each discrete service delivered in the care cycle.

Known as bundled payments, this model also typically makes a portion of provider compensation conditional on the ultimate health outcomes of patients well after the initial surgery or treatment.

This creates incentives for providers to factor in the downstream effect of their clinical decisions, strive to minimize complications and avoid medically unnecessary care, and make informed tradeoffs (such as whether to recommend expensive hospitalization or cost-effective outpatient care) at various points in the care cycle.

As health systems gain experience with bundled payments, they are developing increasingly sophisticated ways of designing and implementing them and spreading them across the entire health system.

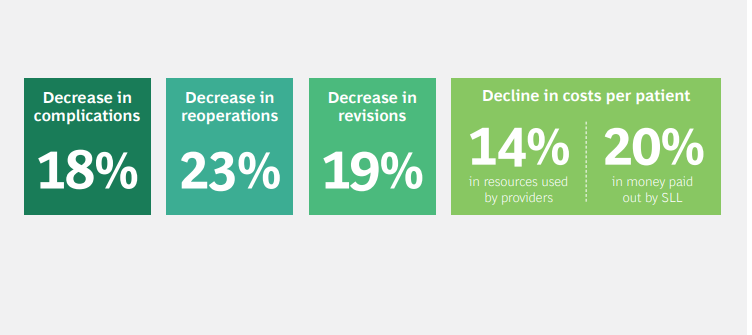

In Sweden, for example, a single pilot project that started in the Stockholm metropolitan area has spread to other regions over the past decade and, in some situations, delivered double-digit improvements in both health outcomes and costs. (See the sidebar “Sweden’s Expanding Program of Bundled Payments.”)

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

3.Population-Based Payments

A third value-based payment model pays a predetermined fee to cover all the health needs of each person in a given patient population. The classic example is capitation.

Capitation gives providers a powerful financial incentive to manage total system costs.

In effect, providers take on the financial risk of delivering cost-effective care. To the degree that they can keep costs under the capitated payment, providers benefit financially; to the degree that they cannot, providers suffer losses (although most capitated systems insure providers against extreme outlier cases).

In order to deliver improved health care value, however, capitation must be combined with systematic tracking of health outcomes for specific patient groups or paired with a bonus for delivering high-quality care.

This ensures that cost savings are not achieved through rationing or other practices that come at the expense of patient health outcomes.

Capitation has long been in place (often in combination with other forms of value-based payment models, such as bonuses or bundled payments) at US integrated payer-providers, such as Kaiser Permanente and Intermountain Healthcare, both of which are acknowledged as leaders in value-based health care.11

But implementing capitation is complex, and not every health system or provider group has sufficient capacity, scope, and the necessary managerial capabilities to administer it effectively. Because capitation requires providers to function akin to an insurer and manage financial risk, it works best when providers can manage the risk across a large population of patients. For example, early experiments in using capitation to manage system costs in the UK foundered because of the narrow scope of the initiatives.

Primary care providers assumed risk for the total cost of primary care but without any financial liability for downstream care in specialist or tertiary settings. As a result, capitation did not really function as an effective incentive for managing total system costs.12

Given this complexity, many health systems are experimenting with other ways to focus providers on population-wide quality and costs.

One approach is to use proxies for total population quality and costs, such as the ACO shared-savings program discussed above.

Another is to create targeted capitation payments for specific population groups (for example, healthy newborns or all patients suffering from diabetes).

Capitation is used in New Zealand for primary care, in the UK for mental health, and in the US by Medicare Advantage programs (which are offered to Medicare patients by US private insurers).

The latter have been shown to deliver better health outcomes than traditional fee-for-service Medicare programs at nearly one-third the cost.13

Originally published at https://www.bcg.com on January 8, 2021.

To download the PDF open the URL below:

http://image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-Paying-for-Value-in-Health-Care-September-2019_tcm9-227552.pdf