World Economic Forum

In collaboration with Boston Consulting Group

January 2020

Foreword

Four years after world leaders met in Paris to agree on the historic Paris Climate Agreement, it is time to take an honest look at the progress on global climate action to date.

This World Economic Forum and Boston Consulting Group report examines what corporations, governments and civil society have achieved since the accord was drafted in 2015 and assesses the current state of global climate action. This full report, The Net-Zero Challenge: Fast-Forward to Decisive Climate Action, follows “The Net-Zero Challenge: Global Climate Action at a Crossroads” Briefing Paper published in December 2019.

The findings for this report are based on quantitative and qualitative assessments of governments, corporations, investors and societies. We conducted interviews with 13 climate experts and 24 CEOs and executives of leading companies across all sectors — from energy and industrial firms with high direct emissions, to technology, service and consumer businesses with significant influence over the emissions of their supply chains and products. We analysed corporate data from CDP, a non-governmental organization that collates voluntary emissions disclosures from nearly 7,000 large companies, monitors global emissions and assesses policy frameworks from governments. Our analysis was supplemented with additional research from the Energy Transitions Commission (Mission Possible), International Energy Agency, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, United Nations Environment Programme, Climate Action Tracker and World Resources Institute, as well as previous work by Boston Consulting Group.

At this year’s World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos-Klosters, climate change is high on the agenda. The year 2020 marks the fifth anniversary of the Paris Agreement, and there are high expectations that the 26th UN Conference of the Parties (COP26) in 2020 will deliver a meaningful international response to the climate crisis. With this crucial milestone ahead, we have an opportunity to build a strong, unified call for accelerated action among business and government leaders.

We must turn the trajectory of greenhouse gas emissions around to ensure that global warming stays within safe limits. While the risks of inaction are mounting, it is still possible to prevent the worst effects of global warming. The costs of abatement are falling and the technological solutions needed to decarbonize our economies are available.

It is within everyone’s power and responsibility to act. This report aims to help clarify the path ahead and encourage the decisive acceleration of climate action.

Patrick Herhold

Managing Director and Partner, Centre for Climate Action, Boston Consulting Group

Emily Farnworth

Head of Climate Change Initiatives, World Economic Forum

Executive summary

In 2015, world leaders met in Paris and agreed to limit a global temperature rise by the end of the century to well below 2°C and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5°C. In the past decade, however, emissions have continued to increase at a rate of 1.5% per annum. A reduction of approximately 3–6% per annum between now and 2030 is needed to limit global warming to 1.5–2°C.[1]

Key messages:

- Progress on climate action to date has been limited

- Since progress in international negotiations is disappointing, corporations and governments need to move unilaterally.

- Corporations can accelerate individual action and commit to meaningful short- and long-term reductions

- Ecosystem actions can overcome barriers, through collaborations along value chains or with industry peers.

- Investor action can enable transparency and support long-term decarbonization plans

- Governments can unilaterally enact national regulation to reduce emissions immediately

- Individuals need to drive climate action in their roles as consumers, voters, leaders and activists

- The world is at a crossroads: We must fast-forward to decisive and cohesive action

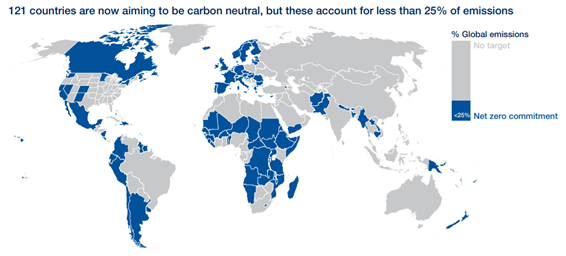

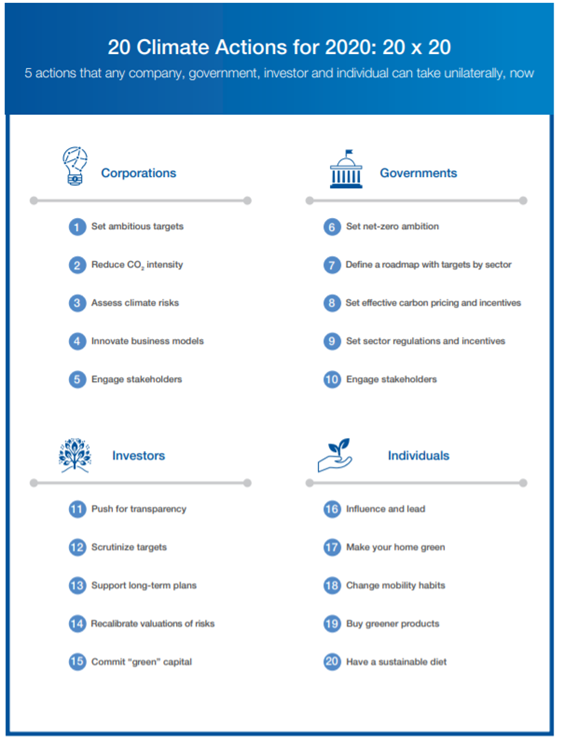

Progress on climate action to date has been limited. On the government side, while 121 countries have now committed to be carbon neutral by 2050,[2] they account for less than 25% of emissions. None of these countries are among the top five emitters, and few, in spite of the commitment, have enacted policies that are robust enough to produce the desired effects. On the corporate side, only a minority of companies fully disclose their emissions. Even fewer have emissions targets or are in the process of making reductions in line with the Paris Agreement trajectory.[3] And while investors have begun to recognize the importance of assessing climate-related risks, liabilities and opportunities, much of their day-to-day decision-making continues to be dominated by an emphasis on short-term performance. In light of this global inertia, public pressure and global activism have surged in recent years, especially among the youth and in Western countries. However, public education on the threat of climate change and related climate action is still insufficient to make this a global phenomenon.

Since progress in international negotiations is disappointing, corporations and governments need to move unilaterally. The world needs cohesive and swift global policy action — and progress is urgently needed at the Annual Meeting in Davos-Klosters and the COP26 this year. But with the slow pace of international climate negotiations to date and the complex political context, the reality is that a global consensus will very likely not be established soon enough to counter the crisis. Individual governments and corporations can and should move ahead with unilateral initiatives; it is about realizing savings from efficiency improvements, managing risks, pursuing new opportunities and maintaining the long-term licence to operate. While no single actor can halt global warming alone, efforts by leading industrial nations or large corporations can have a multiplier effect.

Corporations can accelerate individual action and commit to meaningful short- and long-term reductions. Companies in all sectors can do much more to reduce the emission intensity of their business and supply chains through measures that cost them little or nothing, and can offset residual emissions. All should actively monitor and manage their climate-related risks and increase their efforts to achieve a 1.5–2°C world (for example, with internal carbon pricing), anticipating a future with more stringent policies and greater societal mobilization. Most can develop new business models that contribute to achieving a low-carbon economy and capitalize on the new value pools for “green” products and services.

Ecosystem actions can overcome barriers, through collaborations along value chains or with industry peers. It will take a joint effort to overcome existing transformation barriers in sectors where decarbonization costs are too high for individual companies to bear alone. Through cooperation in coalitions, companies can share the risks of technology development and coordinate related investments in the development of low-carbon solutions. They can generate a demand signal through joint commitments or standards, and set up self-regulating bodies in areas where government policies fall short.

Investor action can enable transparency and support long-term decarbonization plans. Investors can coordinate to define and apply standards for disclosure and reporting. Such efforts can encourage companies to address their climate-related risks. Even more importantly, investors can increase scrutiny on long-term climate risks and opportunities, and encourage asset managers to set long-term targets and strategies towards netzero emissions.

Governments can unilaterally enact national regulation to reduce emissions immediately. Many countries can benefit economically from carbon abatement investments. To deliver on the net-zero ambition, they would need to enact ambitious policy frameworks that include a meaningful price on greenhouse gas emissions. However, while carbon pricing is regarded as an effective and necessary lever, it is unlikely to be sufficient. For one thing, abatement costs differ widely across sectors, which implies that carbon prices incentivize some sectors to move earlier than others — while practically all sectors would need to start abating today. Alongside carbon pricing, sector-specific regulations and incentives would promote remedies such as a switch from fossil fuels to renewable energies, electric mobility, efficiency, green building standards — supported by accelerated innovation. As long as the world as a whole is moving slowly, national efforts will also require measures to protect emission-intensive industries from high-carbon, low-cost competition, through mechanisms like cross-border carbon taxes and low-carbon product standards.

Individuals need to drive climate action in their roles as consumers, voters, leaders and activists. The transition to a net-zero economy will be a transformational shift for all of society. Individuals have to take the lead in inciting governments, businesses and every part of society to move.

The world is at a crossroads: We must fast-forward to decisive and cohesive action. The coming decade will determine whether humanity retains a fighting chance to limit warming to 1.5°C or even 2°C. The later action is taken, the more dire our position will become. The technologies for a low-carbon transformation are largely available, the barriers to action are vastly overstated and the consequences of inaction are well known. Climate action is still too often perceived as a cost or a trade-off with other priorities. In light of the facts, it should be viewed as an opportunity for businesses, countries and individuals to create an advantage in building a better, more sustainable world.

Contents

Foreword

Executive summary 5

1. The world needs to get to net zero, yet emissions continue to rise

2. Companies and investors should accelerate individual action — in their own interest

3. Ecosystem actions can help overcome barriers to transform

4. A call for unilateral government regulation

5. Individuals need to lead the change as consumers, voters and leaders

6. The way forward: An action plan for all stakeholders

Methodology

Contributors

References

Endnotes

1.The world needs to get to net zero, yet emissions continue to rise

The UN Environment Programme’s Emissions Gap Report 2019 found that global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, including from land-use changes such as deforestation, hit a new high of 55.3 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2 equivalent in 2018.[4] Despite commitments from individual governments and companies over the past decade, emissions have risen by 1.5% per year. Should this pattern continue, the world is projected to warm by 3°C to 5°C by 2100, with catastrophic effects on human civilization.

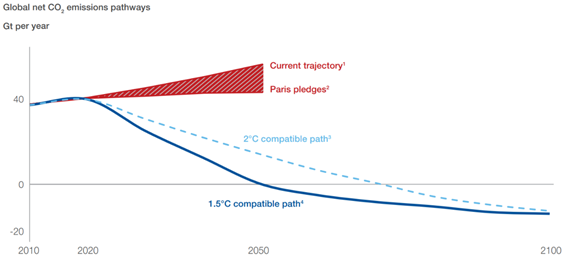

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), limiting global warming to 1.5°C requires net human-caused carbon dioxide (CO2 ) emissions to fall by 45% by 2030 and to reach net zero by 2050[5] (see Figure 1). Even limiting the temperature rise to 2°C will require CO2 emissions to fall by 25% by 2030, requiring a turnaround of the present trend.

Figure 1: The world needs to move to “net zero”, 2010–2100

1. Assumes CO2 emissions grow from 2018 to 2050 at the same rate as the Current Policies Scenario in UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report 2019 (1.1% compound annual growth rate); 2. Assumes countries decarbonize beyond the same annual rate that was required to achieve their INDCs between 2020 and 2030; 3. Assumes a 25% reduction by 2030 and net zero by 2070; 4. Assumes a 45% reduction by 2030 and net zero by 2050. Note: Other GHG emissions are also to be reduced by more than 50% in pathways limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

Sources: IPCC; UNEP, Emissions Gap Report 2019; BCG analysis

Globally, emissions are stagnating or rising in all major economic sectors. Based on today’s policies, this dynamic is not forecast to change over the next 10 to 20 years (see Figure 2). For example:

1. Demand for energy continues to increase — and hydrocarbons are meeting much of the demand. Global energy demand rose by 2.3% in 2018 and is expected to continue to grow by more than 25% between now and 2040.[6] A large part of the energy consumption is coming from emerging economies that are investing in carbon-heavy projects to boost economic growth.

2. Volume growth in emission-intensive industry sectors is projected to continue, for example in cement (growth of 30% by 2040) and steel (growth of 10–15% by 2040). These sectors have few low-carbon alternatives, and those that exist are costly. The demand for plastics, another high-emission industry with limited economically viable low-carbon production alternatives, could increase by up to 150% by mid-century.[7]

3. Hard-to-abate transportation sectors are also still growing considerably. By 2050, freight demand is expected to triple, and demand in aviation will likely more than double.[8]

Figure 2: Major turnaround in emissions trajectories is needed across all sectors, 2015–2050

1. IEA Reference Technology Scenario; 2. IEA Current Policies Scenario only estimates emissions to 2040 — From 2040 to 2050, same compound annual growth rate assumed for each trajectory as from 2020 to 2040; 3. Buildings includes heat, electricity and cooking.

Sources: IEA, Tracking Clean Energy Progress; BCG analysis

A major turnaround in emissions trajectories is needed in all sectors to limit the rise in surface temperatures. The world needs to achieve a net-zero emissions level in order to prevent catastrophic climate change effects.

Governments: Commitments and policies are dramatically insufficient

Before COP25, only 67 of the UN’s 193 member states had a net-zero ambition in place. The number has now increased to 121,[9] showing signs of progress. However, Note: 8 US States — California, New York, Hawaii, Washington, New Mexico, Nevada, Colorado, Minnesota (Washington, New Mexico, Colorado, Minnesota & Nevada committed to 0 carbon energy). Sources: COP25; CAIT data from World Resources Institute and Eurostat; BCG analysis between them, these countries account for less than 25% of global emissions (see Figure 3).

Many of the world’s largest CO2 emitters, in particular, are not doing enough to address the problem. China, which is responsible for a quarter of current global emissions, has reportedly resumed construction of the world’s largest pipeline of new coal power plants. In the United States, which is responsible for the planet’s largest share of accumulated atmospheric CO2, senior government officials are openly denying climate science and backtracking on previous regulations and international commitments, including the country’s commitment to the Paris Agreement.[10]

Figure 3: Few countries have a net-zero ambition to date

Note: 8 US States — California, New York, Hawaii, Washington, New Mexico, Nevada, Colorado, Minnesota (Washington, New Mexico, Colorado, Minnesota & Nevada committed to 0 carbon energy).

Sources: COP25; CAIT data from World Resources Institute and Eurostat; BCG analysis

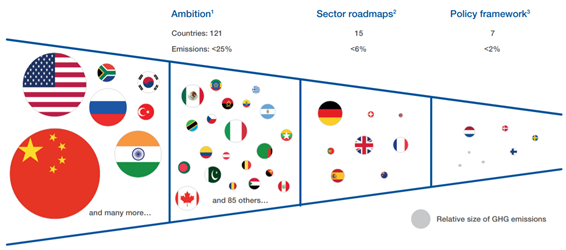

Even the front runners are off track. Of the 121 countries with net-zero goals, only seven have actually broken this target down into intermediate sector-level targets and roadmaps, and have policies in place that could realistically trigger the reductions.[11] Although these seven help point the way for others, their combined GHG emissions account for less than 2% of the world’s total (see Figure 4).

Nordic countries have been among the few to take truly decisive steps, supported by favourable public opinion and social contexts. For example, Sweden’s climate act of 2018 enforces annual reporting, sets targets at 1.5°C or below and calls for forceful climate policy through the country’s dedicated Climate Policy Council.[12] Sweden has set the highest carbon tax in the world, at €114 per tonne,[13] is engaging industry in sector-specific dialogue to create meaningful policies and has invested heavily in R&D and new technology pilots,[14] along with climate-resilient development projects through the UN Green Climate Fund.[15]

The Netherlands has also taken decisive steps, putting in place a Climate Agenda[16] and ambitious targets for renewables, reinforced by subsidies and biofuel mandates. The country has regulations on new building energy performance and aims to phase out gas boilers by 2050, supported by tax breaks and subsidies. Industrial sectors are also subject to energy efficiency and best available technique (BAT) standards.[17]

A number of emerging economies, too, are starting to set ambitious renewable targets, even if they do not yet have a full carbon-neutrality plan. India is currently implementing the largest renewable power programme in the world — targeting 175 GW of installed capacity by 2022. Morocco has developed the world’s largest concentrated solar farm, with the objective of making more than 50% of its electricity generation renewable in just 10 years.[18]

Regions and cities are also moving ahead. Around the world, 398 cities have joined the alliance to achieve net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050,[19] recognizing the benefits of the transition to a low-carbon society. Cities account for more than 70% of global energy-related CO2 emissions and are therefore critical to delivering a climate safe future. Megacities under Deadline 2020,[20] as well as local cities under the Argentine Network of Municipalities — representing over 660 million people — are following a pathway that would deliver emission reductions consistent with 1.5°C.[21] In the United States, eight states are now aiming for zero-carbon energy systems by 2050, including California.

Still, the vast majority of governments have held back from taking decisive action. Despite the positive business case for many countries to act, even if unilaterally,[22] nations often have to overcome considerable barriers, whether perceived or real, including vested interests, polarized electorates and the fear of damaging economic competitiveness.

Figure 4: Only a few countries have a roadmap and robust policies to deliver net-zero ambition

1. Countries with a net-zero ambition; 2. Ambition translated into sector roadmaps with targets; 3. Targets supported by an effective policy framework. Note: Countries with emissions >40 million tonnes and those with emissions >75 million tonnes with a net-zero ambition are represented graphically by a flag.

Sources: Emissions data from CAIT (from the World Resources Institute) and Eurostat; Policy analysis by BCG, referencing the IMF, Climate Action tracker and government websites; BCG analysis

Corporations: Only a minority are taking the lead, but the group is growing

The apparent failure of governments to act increases the responsibility for corporations to fill the void. Recognizing the beneficial business case of taking action early, a number of companies have produced ambitious plans to decarbonize their operations and supply chains, thereby safeguarding future licences to operate, preparing for more demanding future regulation or developing innovative business models. More companies are disclosing their emissions and more are signing up to ambitious reduction targets:

– The Science Based Targets initiative, which recently surpassed 300 member companies — The Business Ambition for 1.5°C pledge, which has reached 177 members[23]

– Commitments, after COP25, of over 500 B Corps to reach net-zero emissions by 2030.[24]

However, these examples constitute a minority, frequently driven by a CEO’s personal convictions and intentions to secure an executive legacy, or by a particularly engaged workforce or investor group. Of the millions of corporations worldwide, only close to 7,000 disclosed climate-related data via CDP.[25] Of those that do report their numbers to CDP, only a third provide full disclosure, only a quarter set any type of emission reduction target, and only an eighth actually reduce their emissions year-on-year (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Too few companies are acting decisively

1. Do not disclose/only disclose partial emissions data; 2. Say there is no facility/source of Scope 1 or 2 emissions excluded from disclosure; 3. Have any form of emission reduction target; 4. Have reduced emissions vs last year.

Note: >250m tonne and < 100 tonne disclosures are excluded, as likely data errors.

Sources: CDP data (2018); BCG analysis

And even where companies do report targets, most still fall below the requirements set in the Paris Agreement. Around 65% of all company targets reported to CDP are short term with an end date of no more than five years. On average, both short-term and long-term targets are about half of what would be needed for a 1.5°C world; short-term targets aim for minus 15% instead of minus 30%, while longer-term targets look for 50% reductions instead of carbon neutrality.[26]

In addition, the lack of common reporting standards makes it hard to compare targets. Companies report very different base and end years. When they commit to targets, they might be referring to absolute emission reduction, emission intensity, renewable energy use, or any other measure, and the volume metrics they use are inconsistent. As a result, to date no robust way of benchmarking corporate climate action exists even among industry peers. This lack of transparency makes it too easy for companies to display policies that are mostly window dressing instead of actually investing in meaningful emission reductions.

Companies are even less rigorous in tracking and addressing the indirect emissions produced by their value chains and products, known as Scope 3. Fewer than one in 10 companies reporting to CDP has a target on these emissions. However, given the potentially enormous leverage large companies have on supplier behaviour, recent announcements that such companies as Apple and Walmart will scrutinize supply chain emissions offer encouragement.

“Climate change is the single greatest threat that humanity faces. Businesses that don’t take climate action will be punished by their stakeholders as well as by the planet.”

Alan Jope, Chief Executive Officer, Unilever, United Kingdom

Investors: Action on long-term climate risks and opportunities is still limited

Investors are in a unique position in the climate debate, given their short-term financial exposure to long-tail carbon-related risks. Corporations will feel the effects of global warming when their markets are disrupted or their assets are stranded, whether due to a climate-change-related disaster, regulatory changes, public pressure or legal action. But well before cataclysmic events become more common — as the general public and financial markets become more aware of climate-related risks to corporate balance sheets — investors are likely to see valuations decline.

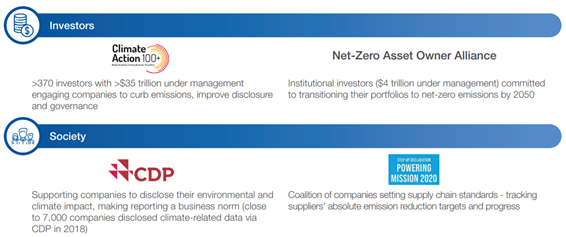

To mitigate this risk, investors have started to put pressure on companies to better understand and disclose their carbon-related risks and develop resilience strategies — individually or through activist groups. For example, Climate Action 100+ has brought together a consortium of investors managing a total of $35 trillion to push for disclosure and emission reductions in their portfolio companies.[27] Private equity firms are beginning to screen corporations for climate-related risks that could lower their value to potential buyers. The UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance has brought together investors managing a total of $4 trillion in assets committed to transitioning their portfolios to net-zero emissions by 2050.[28] There has also been considerable growth in the appetite for green finance products. The issuance of sustainable debt in 2019 is expected to hit a high of $350 billion, 30% above 2018.[29]

On a global scale, however, the impact of investor pressure is still not sufficient. In one-on-one interviews, CEOs say the pressure to deliver short-term returns by far exceeds any demands for long-term decarbonization.[30] Unless this trend changes, CEOs will have little incentive to take decisive action.

Similarly, financial market supervisory boards have yet to take a clear stance on best practices for the low-carbon era. The lack of consistent corporate reporting or a reliable framework for assessing climate risk has been a major barrier to progress. Investors are faced with a plethora of environmental, social and governance (ESG) frameworks, which one major bank CEO described as leading to “real confusion and little action” in the investment world. So far, the voluntary adoption of standards has been no substitute for regulated carbon accounting conventions.

The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which aims to develop voluntary, consistent climate-related financial risk disclosure standards, has seen a steady stream of supporters sign up but, at over 930 organizations to date,[31] still represents a minority of the investment world. To trigger the acceleration that is needed, the adoption of disclosure standards would need to be mandatory.

Public opinion: Pressure is mounting, but not fast enough

Over the past few years, the inertia on the part of the public and private sectors has caused frustration among citizens’ groups throughout the world, triggering a surge in protest and climate activism. Movements like Fridays For Future regularly mobilize millions of people, and the headline-grabbing acts of groups like Extinction Rebellion have helped to build momentum, especially among the youth. Such movements are likely to persist and multiply.

But while pressure from citizens and consumers may be mounting in some geographies, especially in Europe, climate change does not yet alarm the vast majority. Only 16% of adults globally consider climate change to be one of their top three societal concerns, ranking well below unemployment, crime and corruption, according to a September 2019 survey by the market research firm Ipsos MORI (see Figure 6).[32] While the trend is increasing, with a steady rise from 8% in 2016 and 11% in 2018, in many countries it still does not appear among the issues that worry people the most. Moreover, two out of three respondents globally did not even rank it among their top three environmental issues; air pollution, waste generation and deforestation were larger worries, especially in emerging economies.[33] In most cases, citizens are not linking trends in these environmental areas to GHG emissions and the interdependency with global warming.

Until public education on climate challenges catches up, citizen pressure is not likely to be strong enough to force all governments to the table. And by the time climate change starts to have a more visible impact in the daily lives of people around the world, it may already be too late.

Figure 6: Climate change is still not a top concern globally, and engagement varies country-by-country

1. Turkey ranks climate change 16th out of the possible 17 concerns. Note: Representative sample of adults aged 18–74 in the US, South Africa, Turkey, Israel and Canada, and aged 16–74 in all other countries. September 2019: 19,531.

Sources: IPSOS, Global Advisor; BCG analysis

Nevertheless, progress has been made. Many governments are gradually increasing their long-term ambitions and are beginning to implement more rigid emission policies. A number of corporate success stories provide lighthouse examples for others to follow. Companies increasingly disclose emissions, set more ambitious targets and see climate as a driver for business innovation. More have introduced low-carbon business models to provide consumers with a sustainable alternative. Investors are increasing their scrutiny of long-term carbon risk and putting more capital into green financing vehicles. Public awareness around the urgency of the issue is increasing and, with it, broader support for policy measures and evolving customer behaviours. But the most important indicator remains global emissions. As long as these continue to rise, the scale, pace and extent of progress is simply insufficient.

“There is a lot of misinformation about the transition: we need to educate people about the causes of climate change and the solutions.”

Francesco Starace, Chief Executive Officer, ENEL, Italy

2. Companies and investors should accelerate individual action — in their own interest

Companies can and should do much more to bring down their own emissions. Beyond retaining their social licence to operate, this is mainly about companies managing risks, preparing for anticipated changes in regulations and preparing their business models for a low-carbon future.

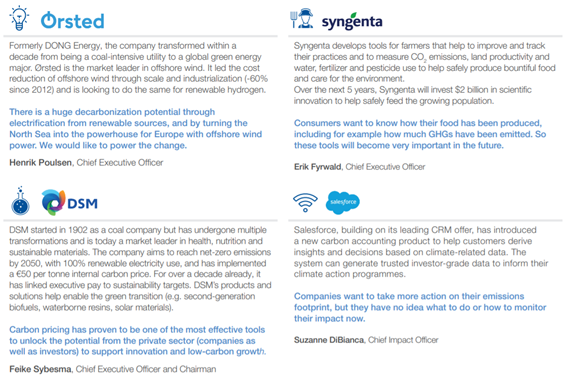

For this report, 24 CEOs and executives and 13 climate experts were interviewed. Selected through their affiliation with the World Economic Forum, these leaders represent a wide range of sectors and geographies — from energy-intensive industrial goods companies, to tech and consumer goods and services firms, from developing as well as developed economies.[34]

All of the executives shared the view that acting on climate is not only a responsibility, but also a source of competitive advantage in their respective sectors — in terms of reducing cost, fulfilling the needs of future customers and attracting the greatest possible talent (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: First movers in every sector are building a competitive advantage

Source: Corporate interviews conducted by BCG in Q3–4 2019; most interviewees are part of the World Economic Forum Alliance of CEO Climate Leaders; Bank of America and Maersk were added according to public statements

Across all sectors, three major levers can enable corporates to radically reduce their emissions and prepare for a decarbonized world, gaining a competitive advantage in the shift to a greener economy (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Corporates need three major levers to tackle climate change

Sources: CEO interviews; BCG analysis

Companies in all sectors can reduce their emission intensity at little or no cost

By accelerating the switch to renewable energy, improving energy and process efficiency in their own operations, and leveraging their buying power to ensure that their suppliers decarbonize, most companies can significantly reduce their own emissions and those of their partners.

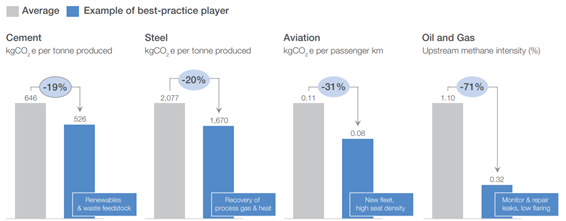

Most companies — even in energy-intensive sectors — can still realize energy and process efficiency gains in the range of 20% (see Figure 9) at little or no cost. Notably, for example, the most efficient oil and gas companies have approximately 70% less methane intensity than the upstream average for the industry, and an International Energy Agency (IEA) analysis shows that more than 50% of fugitive methane emissions can be abated with a positive return.[35] In many instances, such improvements actually provide attractive cost savings opportunities with comparatively short payback periods, and often a viable business case for the expenditure. The Carbon Trust, a global organization that helps businesses develop sustainable operating strategies, has found that among its partners, investments designed to save around 15% of energy consumption yield an average internal rate of return of 48%.[36] Implementing these sorts of levers is a no-regret move for all companies to pursue.

Similarly, most companies can accelerate the transition to renewables by directly procuring renewable power. For example, RE100,[37] an initiative that more than 215 large companies have signed up to, has been instrumental in pushing commitments to 100% renewable energy among leading companies. At a time when the costs of renewable power generation continue to fall, the transition frequently results in net cost savings, or at least works economically, given typical carbon price levels imposed by governments or internally within corporations.[38]

Figure 9: The efficiency potential is still significant in all sectors

Note: The averages for cement and steel are an average across four large players with available data (among the top 10 by revenue); the averages for aviation and oil and gas are reported industry averages; for oil and gas, the best-practice player is a self-reported upstream average across the 13 members of the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative.

Sources: CDP data; Oil and Gas Climate Initiative data; company annual reports; company sustainability reports; BCG analysis

Even where measures are only near-economic, companies should implement them as a means of future-proofing their business against growing external pressure from the public, regulators and investors. Already today, companies with lower emission intensities are traded at higher valuation multiples on stock markets. A recent BCG analysis across a range of high-emission industries found that top-quartile companies in specific ESG metrics (including emission intensity and environmental impact) trade at a premium vs the industry median.[39]

Beyond reducing their own emissions, most companies can do much more to decarbonize their supply chains. By leveraging their significant buying power, many large corporations are able to reduce volumes of GHG emissions that are a multiple of their own operations at limited cost — especially in low-emission industries, such as services and consumer goods. CDP estimates that the Scope 3 emissions (that is, emissions through the supply chain and from the use of products) are on average four times higher than the direct emissions of the companies that report to them.[40] By setting standards on supplier emissions, efficiency or renewable energy consumption, companies can help mobilize the overall decarbonization of the economy and reach the “long tail” of suppliers that otherwise might be too under-the-radar to feel the direct pressure of consumer scrutiny.

This also means that many companies should increasingly be prepared to track and disclose end-to-end emissions to consumers who increasingly demand greater transparency on the products they buy, and to governments that may impose stricter regulations on the carbon content of products sold in their jurisdictions.

Companies in a range of sectors are already moving ahead. For example, Dalmia Cement has achieved the least carbonintensive cement production in the world (approximately 500 kg CO2 e per tonne of cement) by rigorously investing in process efficiency, finding clinker substitutes and increasing the use of renewables.[41] Going forward, Dalmia Cement has the ambition to become the world’s first carbon negative cement company by turning to alternative binders and investing in carbon capture, utilization and storage technology.[42] On upstream emissions, Walmart has launched Project Gigaton that aims to reduce one gigatonne of GHG emissions from its supply chain between 2015 and 2030 (cumulatively), half of which is expected to come from suppliers operating in China. In 2017, Walmart launched a sustainability toolkit to help suppliers track and reduce emissions. In the first two years since the launch, the initiative reported over 93 million tons of avoided CO2 e.[43]

For residual, harder-to-abate emissions, companies can look at offset measures with real additionality[44] and impact. This can be a useful lever particularly in the initial, transition phase.

Companies should de-risk their investments to avoid stranded assets

At the same time, companies should aim to de-risk their investments for the low-carbon transition. In ambitious abatement scenarios, nearly all current investments in coal, and an increasing share of investments in oil, gas and related infrastructure, could be challenged. This increases the risk of investments becoming stranded. Even for industrial companies, the investments they make in new assets, long-life asset upgrades or new product development should be carried out with a low-carbon/carbon-neutrality target in mind to avoid potential future write-offs.

According to the intergovernmental International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), a global 2°C pathway would result in an approximately $5–10 trillion decline in coal, oil and gas infrastructure value until 2050.[45] The risk of retrofit costs to industrial plants and building developers, which rely on fossil fuels for heat or cooking, is valued at another $5–10 trillion over the coming decades.[46]

To better align their investment decisions to this risk, companies are starting to implement internal carbon prices. For example, Unilever[47] has been pricing emissions from its manufacturing operations since 2016 by deducting costs from business divisions’ capital budgets. Divisions in turn compete to use the funds (currently about €50 million annually) to instal clean technology at operating sites.

“To date, several of our sites have now achieved the feat of 100% renewable energy for both heat and power by investing funds from our internal carbon pricing in clean technologies, increasing our energy efficiency, and in switching to renewable energy sources. This future-proofs our business from future carbon taxes and regulation.”

Alan Jope, Chief Executive Officer, Unilever, United Kingdom

Enel has fully integrated sustainability into its strategy and operating model to deliver long-term value and become the largest global operator of renewables and networks.[48] The energy company aims to spend 50% of proceeds within the plan period (by 2022) to accelerate the deployment of new renewable capacity and progressively substitute coal generation.[49] Enel has also increased its use of sustainable finance, to reach approximately 43% of total company debt by 2022 and 77% by 2030 (today: 22%). The bonds have allowed the company to sharply reduce its financing costs.[50]

“Enel is now a more sustainable, efficient and profitable organization, with a substantially lower risk profile and a greater capability to rapidly adapt to change.”

Francesco Starace, Chief Executive Officer and General Manager, Enel, Italy

Companies should innovate to realize opportunities from low-carbon business models

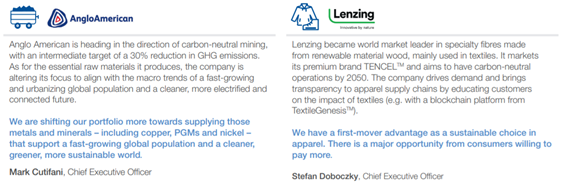

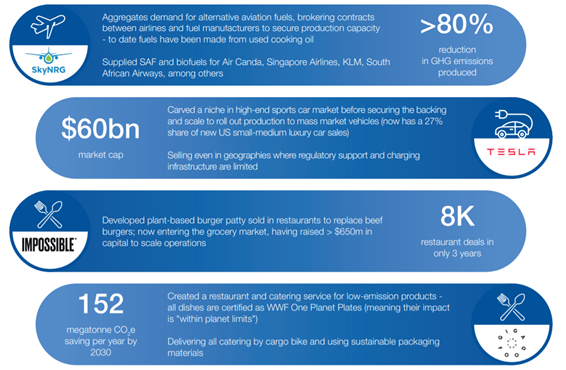

Moving to a Paris-compatible pathway would imply a significant, and sometimes existential, transformation for companies in many industries. And while many companies would not be able to realize this full transformation alone, most can accelerate progress by offering low-carbon products and services and by involving willing consumers in their decarbonization journey. Even in the harder-to-abate sectors, companies can turn a first-mover disadvantage into an opportunity.

In the wake of growing global consciousness about the climate crisis and consumers’ desire to limit the impact of their consumption footprint, new markets for lower-carbon products are taking shape. A wealth of examples have been available from companies in recent years, which are generating significant value from credibly serving these markets — by decarbonizing rapidly, by offering consumers a “green choice” or by innovating to help customers bring down their own emissions (see Figures 10 and 11). Digital technologies are key enablers of this innovation.

“The revenue uplift from introducing new climate-friendly products and services represents a major opportunity for forward-looking businesses, and investors and customers are showing a preference for innovative companies that are tackling climate change. The use of mobile technologies, such as machine-to-machine (M2M) and the internet of things (IoT), enabled a global reduction in GHG emissions of more than 2 billion tonnes last year.”

Mats Granryd, Director-General, GSMA, United Kingdom

While existing technologies can decarbonize most emissions, innovation is still needed to achieve a net-zero emissions target by 2050. Companies and institutions should proactively pursue innovation-delivering solutions that meet society’s needs in new ways. At the COP21 in Paris in 2015, Mission Innovation was launched with the specific objective to support the accelerated uptake of clean energy and related infrastructure; it is now developing a framework to identify those innovations that are compatible with a 1.5°C world.[51]

In energy, for example, a wide range of potential opportunities is arising from energy transitions: large-scale or decentralized renewables, advanced mobility and new fuels, energy efficiency solutions, circular economy business models, carbon capture usage and storage (CCUS), and hydrogen technologies. Energy incumbents can look to diversify or reposition their portfolio towards new technologies and business models, becoming key actors and partners of climate action. However, they should also consider the specific capabilities required and the materiality and scale of returns offered.

The transition to net zero will offer huge opportunities for entrepreneurs and businesses to address societal needs in new, improved ways.

Figure 10: Companies are shifting to greener business models

Source: Specific companies’ office for sustainability or external communications

Figure 11: Innovators are seizing opportunities to start new businesses

Source: BCG analysis

Investors are a critical enabler of corporate climate action

Investors have a pivotal role to play in triggering and facilitating the adaptation of corporate strategies, given their inherent interest to “de-risk” the terminal value of their investments. Growing investor scrutiny has motivated a number of companies to accelerate climate action, but the momentum needs to increase further, providing clear guidance to management teams around shareholder expectations.

Investors should issue a much stronger call for transparency and disclosure. Too many companies lack awareness of their economic efficiency potential, as well as of the climate-related risks to their business model. Rigorous disclosure demands would force companies to create this awareness and to develop resilience strategies for a 1.5°C or 2°C world. It also makes assessing these risks more straightforward for investors and creates better comparability across companies within an industry, hence increasing the efficiency of capital markets.

Moreover, investors should themselves recalibrate their risk assessments. They need to be sure that they understand the impact of various warming scenarios on their assets, from operational disruption to health and safety or site closure risks, and that the long tail risks of both climate change and climate action are fairly reflected in the valuations they assign to companies. For example, an estimate by Citigroup shows that under a 2°C path, fossil fuel reserves valued today at around $100 trillion would need to remain in the ground.[52] Similarly, ambitious decarbonization investments may not contribute much to a company’s short-term returns, but may significantly de-risk long-term earnings.

Finally, investors can direct investments into zero- and low-carbon technologies and offerings. A growing appetite for green bonds and other sustainable finance products sends a powerful signal that there is support for decarbonization initiatives, and has enabled some of the companies profiled in this report to move forward. In the future, even more investors may recognize the opportunities for businesses in the transition.

Some leading examples of action are Bank of America’s Environmental Business Initiative and Santander’s Responsible Banking Targets. Bank of America has committed to invest an additional $300 billion in capital by 2030 in sustainable energy and transportation, climate resiliency and clean water with the belief that this will support innovation towards a low-carbon, sustainable economy and enable it to deliver long-term value. Santander aims to facilitate €220 billion of financing linked to the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, with an emphasis on green finance to help tackle climate change.[53]

Another example is UBS, a leader in global wealth and asset management, which is actively addressing the growing investor appetite for directing capital into climate solutions. UBS has developed, for example, a selection of products allowing its institutional clients to identify the carbon intensity of their investments and reducing exposure to, rather than excluding, companies with higher carbon risk, in order to pursue strategic engagement with these companies. Furthermore, UBS has committed to integrating ESG assessments, including a dedicated climate dimension, into all fund and exchange-traded fund onboardings for its private clients.

“We want to be a leading financial provider enabling investors to mobilize capital towards the achievement of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and the orderly transition to a low-carbon economy.”

Sergio Ermotti, Group Chief Executive Officer, UBS, Switzerland

To enable or amplify their actions, companies should engage in ecosystems and with policy-makers

Even today, companies can — and should — do a lot more individually to decarbonize, to realize savings, to de-risk their asset base and to start the transformation of their business models with strong positive business cases and shareholder return stories. For many, even full decarbonization is possible without significant (relative) cost to their business.

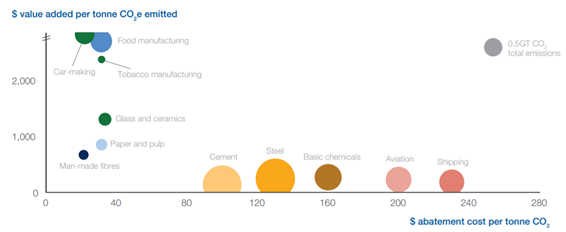

But this does not hold true for all. For companies in hard-to-abate sectors like steel, cement, chemicals, aviation and shipping, investments in ambitious emission reduction targets are an enormous financial challenge and can be an existential risk. These sectors create comparatively low value per tonne of CO2 emitted. At the same time, abatement is much more expensive, not least given that the needed technologies are often still in early development stages (see Figure 12). In steel and cement, alternative processes or materials — hydrogen-based direct reduction process for steel, innovative binders for cement, CCUS for both — are still in the research or pilot stage, and entail around 100% additional cost per tonne.[54] For aviation and shipping, hydrogen-based synthetic fuels like green ammonia and e-kerosene are yet untested and very far from economically feasible, entailing costs that are likely more than double those of traditional fuels.[55] The chemical industry would need to convert many high-temperature processes for producing base chemicals, adding a cost burden of at least 50% — and could face an even larger challenge if it were to replace fossil fuels from its feedstock.

Figure 12: Some high-emissions sectors face a huge financial challenge

Note: Total emissions for chemicals refer to basic chemicals and fertilizers; glass and ceramics total emissions size reflects China only due to data availability; lower bound of total emissions for food manufacturing shown can be up to 2.4Gt CO2.

Sources: Energy Transitions Commission, Mission Possible (2018); company reports; IEA; Oxford Economics; Carbon Trust; Our World In Data; “Energy Consumption and Carbon Dioxide Emissions of China’s Non-Metallic Mineral Products Industry” (Sustainability, vol. 6, 8012–8028, 2014); “Cigarette Smoking: An Assessment of Tobacco’s Global Environmental Footprint Across Its Entire Supply Chain” (Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 52, no. 15, 8087–8094, 2018); BCG analysis

To make it possible for companies in these sectors to decarbonize, and to accelerate emission reduction activities in all others, a number of barriers to action still need to be overcome (see Figure 13). Many countries still lack adequate carbon pricing and supportive regulation to motivate full decarbonization. Technology development in some applications still needs to accelerate. Moreover, a lack of transparency, uncertainty about consumers’ willingness to pay and fear of investor focus on short-term results still keep many companies from moving faster to decarbonize their operations and supply chains, or innovating to create greener products.

But while these barriers may prevent companies from moving to net zero today, all industries should understand the circumstances that can make it possible to get there. Accordingly, even some companies in hard-to-abate sectors have come forward with ambitious commitments. For example, while acknowledging that there is not yet an economically feasible path for doing so, both the container shipping company MAERSK and the steel producer ThyssenKrupp have announced plans to move to carbon neutrality by 2050, as well as to implement ambitious medium-term targets. Repsol has become the first oil and gas company to set a net-zero ambition by 2050, with stringent intermediate targets and, in the chemicals sector, LANXESS is aiming to be carbonneutral by 2040 and has linked management bonuses to its emissions goals.

Figure 13: Significant barriers to broader and bolder corporate climate action

Source: Corporate interviews conducted by BCG in Q3–4 2019; most interviewees are part of the World Economic Forum Alliance of CEO Climate Leaders

Ultimately, companies can increase their climate ambition in the very interest of their business. But significant barriers must be met to achieve a net-zero emissions target. For broader and bolder climate action, business leaders will need to work with their peers, suppliers, customers and governments.

3. Ecosystem actions can help overcome barriers to transform

Ecosystem initiatives can help overcome economic and other structural barriers by fostering collaboration within sectors or across value chains. This is particularly true for those sectors where commercial risks significantly limit the room for individual corporate action. By enabling willing actors to overcome restrictions on individual companies and agree on risk-sharing mechanisms, they can create the competitive level playing field necessary for companies to act. More generally, such ecosystems can help accelerate the speed and scale of change.

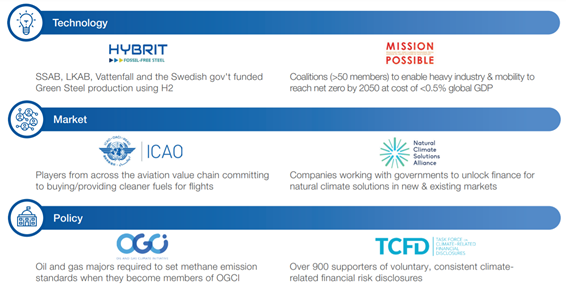

Where there is technology uncertainty and the costs of new technology expansion are high, ecosystem collaborations can allow players within a sector or across a value chain to share the costs and risks (see Figure 14). For example:

The Hybrit initiative has brought together players across the value chain to produce zero-carbon steel with hydrogen-based direct reduction technology (DRI). The initiative’s pilot plant is co-funded by Vattenfall, which provides renewable electricity for green hydrogen electrolysis; LKAB, which supplies direct reduction iron ore pellets; and SSAB, which will manufacture the steel. The project aims to start full production by 2035.[56]

The Mission Possible Platform,[57] developed by the Forum and the Energy Transitions Commission, is building similar ecosystem initiatives to develop viable decarbonization pathways for transport, aluminium, chemicals and cement, as well as similar projects in steel. Coalitions of leading companies within each sector are being established to provide the critical scale needed for financing technology pilot projects, and they are inviting co-investment from governments in public-private partnerships.

In sectors where the market for low-carbon products is uncertain, causing corporations to hesitate to commit capital, ecosystem collaboration can create a critical demand signal to kick off a market. For example:

Clean Skies for Tomorrow,[58] an initiative developed by the International Civil Aviation Organization and the Mission Possible Platform, brings players in the aviation industry together with large-scale aviation customers and fuel suppliers to build critical demand for synthetic aviation fuels through coordinated offtake commitments. This enables fuel providers to commit the needed investments in production capacity and airports to provide the necessary infrastructure.

Initiatives like Renewable Energy 100 (RE100)[59] and Electric Vehicle 100 (EV100), in which member companies commit to procuring 100% renewable power and electric vehicles, respectively, have been successful in accelerating demand for green technologies and developing supporting infrastructure (e.g. for vehicle charging).[60]

Similarly, the Natural Climate Solutions Alliance aims to increase nature-based solutions to climate change by developing a market for credible carbon credits based on agricultural and forestry measures. Corporate commitments to buy carbon credits provide the incentive for farmers to change their practices and create a market for forestry management solutions to develop and grow.

Where a lack of climate policies has led to inertia among businesses that are concerned about abating their emissions while competitors continue to pollute, industry coalitions can overcome this paralysing competitive dynamic, either through self-regulation or by coordinating support for more ambitious government policy. For example:

The Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) commits its member companies (13 of the largest global oil and gas majors) to joint emission reduction targets with regular monitoring and reporting. Members have agreed to reduce collective average methane intensity from 0.32% to 0.25% by 2025, saving 600,000 tonnes of methane emissions annually (15 million tonnes CO2 e).[61]

The Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition[62] brings together leading companies that advocate for carbon pricing. In the absence of ….sufficiently stringent pricing imposed by governments, many members of the coalition impose internal carbon prices to prepare for likely regulation, and voluntarily realign their investment strategy with a decarbonized world. More momentum behind this initiative would build support for what is widely considered the most effective decarbonization policy lever available to governments.

The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)[63] encourages companies to voluntarily commit to comprehensive and consistent climate-related financial risk disclosure standards, which so far are not a mandatory element of financial disclosure. Currently over 900 supporters strong, TCFD provides the most widely-accepted guidance on how companies should report their climate risks. It thereby creates much needed transparency for investors, and forces companies to develop strategies that are resilient to a 2°C world.

Building on the transparency from initiatives such as TCFD, investor coalitions can put pressure on companies to align their strategies with a low-carbon world and invest in de-risking their portfolio and asset base. For example:

The Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance,[64] a coalition of institutional investors with nearly $4 trillion under management, has committed to transition its portfolios to net-zero emissions by 2050. Members include some of the largest insurers and pension funds in the world, building critical scale to support longer-term decarbonization investments and the development of low-carbon business models.

Climate Action 100+,[65] a group of more than 370 investors with $35 trillion in assets under management, engages companies to commit to climate-related disclosure, to curb their own emissions and to develop more rigid internal carbon governance.

Finally, ecosystem action can help to leverage the power of public scrutiny in building momentum for emission reductions, and to signal commitments to action among large firms. For example:

CDP[66] is a not-for-profit organization that supports companies to disclose their environmental and climate impacts. It aims to make environmental reporting and risk management a business norm, and to drive disclosure, insight and action towards a sustainable economy. In 2018, nearly 7,000 companies answered CDP questionnaires, disclosing data on emissions and their broader approach to climate change.

The Step Up Coalition[67] secures commitments from corporates to decarbonize their supply chains (Scope 3 emissions). Scaling up this effort could provide a huge lever for emission reductions, especially in consumer-facing companies under increasing public scrutiny to improve the environmental credentials of the products they sell to customers.[68] Considering the relatively lower cost increases borne by consumers of “greener” products vs the cost increases for producers of those products, aligning the supply chain from the demand side could make decarbonization more feasible all along the value chain (see Figure 15), and will become increasingly important as consumers demand more transparency and better carbon credentials from firms in the future.

Figure 14: Ecosystems can help overcome barriers

Source: BCG analysis

Figure 15: End consumer cost increases of “green products” are limited

1. Ethylene case study, which assumes $1,000 per tonne of ethylene, but the price can vary greatly.

Source: Energy Transitions Commission, Mission Possible (2018)

As long as governments are failing or unwilling to regulate, ecosystem action can help amplify the impact of individual companies — by creating otherwise unattainable scale, by de-risking investments, by focusing buying power and by increasing public scrutiny. Nonetheless, even large private-sector coalitions cannot be long-term substitutions for robust policy measures. Such initiatives still rely on willing and committed individual actors, and the risk remains that there will be too few of these or that their commitment will be limited. These efforts are a great accelerator of change but are unlikely to deliver on the needed net-zero ambition on a global scale.

Therefore, major policy action from governments will be needed to solve this challenge, in the form of carbon pricing and much more stringent sector-level regulation.

4. A call for unilateral government regulation

In the end, Paris Agreement targets will be achievable only with serious policy action. Despite the significant progress from corporate — and individual — frontrunners, the individual case for change will likely remain too small for many to act, especially at the pace that would be required to deliver on Paris commitments. Getting to net zero therefore requires a serious increase in government action, through meaningful carbon pricing, accompanied by sector-specific regulations. And as long as progress in multilateral negotiations remains slow, the best hope for achieving meaningful short-term progress is through governments acting unilaterally. For many countries, doing so would actually benefit their sector, and the risks of losing industrial competitiveness are overstated. Providing regulatory clarity now will actually help corporations to plan the transition ahead of time. However, for those countries that do move ahead unilaterally, protective action would be needed to shield a few emission-intensive industries from international high-carbon competition.

The Paris targets are achievable only with serious policy action

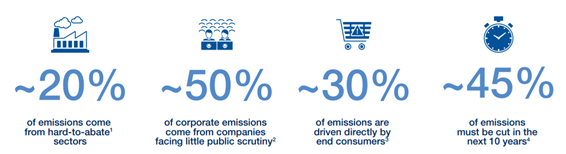

In certain high-emitting sectors in industry and transport, decarbonization costs will remain high. These sectors account for approximately 20% of global emissions[69] and will require government regulation to support their transition to low- or zero-carbon technologies. Agricultural emissions are equally hard to address, given the fragmentation of suppliers and the price-competitive nature of a large share of their products.

While many large companies have been motivated to act progressively on climate change thanks to public scrutiny and the desire to differentiate their brands vis-à-vis consumers, employees and investors, the long tail of companies that undergo little or no public scrutiny is significant. Companies that do not have strong end-customer brands, are only medium-sized or operate in countries with a limited focus on climate make up a significant share of emissions — 50% of corporate emissions are not disclosed to CDP[70] — but have far fewer incentives to move unless they face regulatory pressure.

A significant share of emissions are directly driven by individuals — through their choice of transportation, home energy sources, food and daily purchases. To achieve Paris targets, billions of people around the globe will need to make different choices, often against microeconomic incentives. Only regulation can shift these consumer habits on the scale needed.

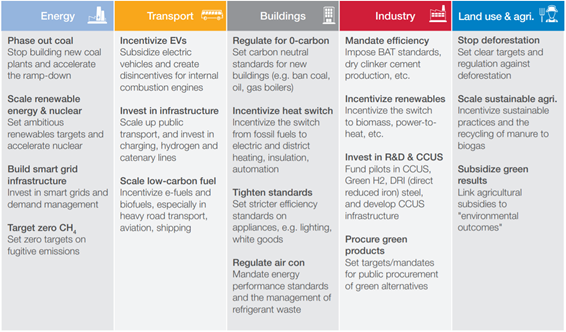

Ultimately, time has run out. Past inaction has dramatically increased the pace at which the world needs to decrease emissions. Complying with 1.5–2°C pathways would require drastically reducing emissions in the next decade. Voluntary action and unregulated markets will not deliver that shift. Hence, governments need to step in to drive the change (see Figure 16).

“We need to halve emissions in the next 10 years. For that we urgently need bold political and corporate leadership and action.”

Henrik Poulsen, Chief Executive Officer, Ørsted, Denmark

Figure 16: Paris targets are not achievable without policy action

1. The hard-to-abate sectors are considered to be cement, steel, iron and other metals (including aluminium), aviation, shipping and chemicals (as per CAIT and IEA emissions data); 2. Emissions from companies that do not disclose to CDP (corporate emissions taken as all those that are not related to buildings, agriculture and light road transport); 3. End consumer emissions are considered to be emissions from buildings (cooking, power, heating/cooling), light road transport and agriculture (as per CAIT and IEA emissions data); 4. The IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming (2018) highlights the need to cut emissions by 45% by 2030 to keep warming below 1.5°C.

Sources: CDP 2018 emissions data; CAIT (World Resources Institute), latest data available at the country level; IEA, Tracking Clean Energy Progress 2017; BCG analysis

Governments need to act now, even if that means acting unilaterally first

Of course, cohesive multilateral policy coordination would be the best solution for halting the climate crisis; decisive progress is therefore needed at COP26 in Glasgow in late 2020. But given the slow pace of multilateral progress, including at the latest COP25,[71] and the complex current geopolitical context, the reality is that a global consensus will very likely not be established soon enough to counter the crisis. Individual governments therefore need to act unilaterally to achieve meaningful progress. And while this will not be sufficient to achieve global climate ambitions in the long run, it is the only realistic path to accelerating emission reductions today.

The good news is that fear of a “first-mover disadvantage” for countries that take early action on carbon abatement is largely unfounded. Remarkable advances in low-carbon technologies are putting emission reductions in many sectors well within technical and economic reach. For many countries, the benefits of higher investment activity and saved reductions in fossil fuel imports outweigh microeconomic costs. This effect holds stronger if a country is highly dependent on fossil fuel imports and the cheap cost of capital. As a result, there are a number of natural “willing actors” who would actually have an incentive to step forward unilaterally, including some of the largest emitters on the planet (Europe, the United States, China, and others).[72] The latest proposal of the European Green Deal, presented in December 2019 during COP25, is an example of decisive unilateral action (by a small, coordinated coalition of countries).[73]

The fear of losing economic competitiveness is overstated

One of the most common arguments against ambitious unilateral emission regulation is that it puts industry competitiveness at risk. When companies are forced to pay high carbon taxes in one country but not in others, they might move abroad to protect their competitiveness, thereby shifting the overall emissions but doing nothing to reduce them — a dynamic commonly known as “carbon leakage”. In countries that regulate, this would harm competitiveness and hence economic growth, whereas countries that do not regulate might even flourish from more industrial companies relocating there — a classic “prisoner’s dilemma”.

But while this threat is certainly real in principle, its extent is commonly overstated.

First, a 2019 report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing and Competitiveness recently found that setting appropriate sector-specific carbon taxes has only negligible impact on competitiveness.[74] More importantly, a significant share of emissions is generated in sectors in which regulation has very manageable “leakage risks”, or none at all. For example, transportation, buildings and power generation are largely local sectors that are not in regional or global competition.

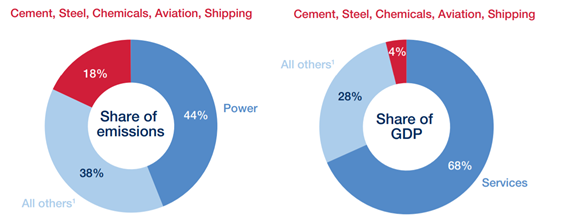

Second, the risk of losing competitiveness mostly affects only a few, very emission-intensive industry sectors; steel, primary metals and base chemicals are the industries most impacted. These are followed by cement, which has more limited leakage risk given the adverse economics of longer distance transport. For aviation and shipping, the risk of refuelling elsewhere is larger than the risk of full relocation. Taken together, these “leakable” sectors make up around 20% of global emissions, but less than 4% of world GDP[75] (see Figure 17).

This is not to say that leakage risk can be ignored. In the absence of a global level playing field, progressive countries will need to safeguard affected industries by imposing protective measures against high-carbon competition or supporting their emission reduction journeys. But a problem that affects less than a 20th of any country’s GDP should not prevent global climate progress. Most countries are economically strong enough to support the decarbonization of these industries. And the industries are few enough in number that individual, tailored solutions can be implemented. Carbon pricing has proven to be one of the most effective tools to unlock the potential from the private sector (companies as well as investors) to support innovation and low-carbon growth.

“Carbon pricing is only one of many elements determining global competitiveness and plays a smaller role than other factors, for instance, labour and infrastructure.”

Feike Sybesma, Chief Executive Officer and Chairman of the Managing Board, Royal DSM, Netherlands

Figure 17: Carbon leakage risk affects a small part of the economy

1. All others includes construction and manufacturing of clay, glass, man-made fibres, plastics, rubber, as well as auto parts, which are downstream of some “at risk” sectors (e.g. steel, cement).

Sources: IEA; CAIT; UNEP, Emissions Gap Report 2018; OECD; IPCC; Oxford Economics; BCG analysis

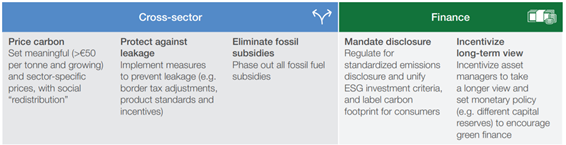

The need for meaningful carbon pricing and sector-level regulations and incentives is urgent

So how can governments regulate emissions most effectively? Unfortunately, no single silver-bullet solution exists. An ambitious policy framework would need to include meaningful carbon pricing, but also a number of sector-specific regulations and incentives promoting remedies such as a switch from fossil fuels to renewable energies, electric mobility, efficiency, green building standards — supported by accelerated innovation. To ensure public acceptance, the policy framework would also need to ensure a fair distribution of the burden and protect the few industry sectors that suffered competitive imbalances otherwise.

The first and most effective mechanism for governments to enact is a meaningful price on carbon emissions. Carbon pricing is widely recognized to be the most impactful and cost-effective way to decarbonize the economy[76] and is endorsed by every major multilateral institution, including the International Monetary Fund, the UN and the World Bank. Studies suggest that to exert sufficient impact, the price of carbon needs to be set at levels of around $40–80 per tonne, escalating to $50–100 by 2030.[77] It is more effective if price development is planned in advance to provide investment security. And given that abatement costs differ structurally sector-by-sector, sector-specific pricing might actually be the most effective strategy, even though there are different schools of thought.[78]

Despite such widespread endorsement, only a minority of countries currently have carbon pricing in place — and many of those have not set it at a sufficiently high level. In a 2018 assessment, the OECD found that in 42 countries that have carbon prices in place, they are “falling well short of their potential to improve environmental and climate outcomes”.[79] The World Bank has demonstrated that less than 5% of emissions are currently priced at levels consistent with reaching the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement.[80]

One of the reasons governments so far have been loath to implement strong carbon pricing schemes is fear of a lack of public acceptance — as witnessed by the gilets jaunes riots in France that began in November 2018. This concern should be taken seriously. Consequently, ambitious carbon pricing schemes have worked best in places where governments have combined them with mechanisms that ensured “fair” (for lack of a better word) social burden sharing and a just transition, through progressive phasing and effective redistribution mechanisms, as well as support for workers in industries more heavily impacted by the transition.

For example, Policy Exchange, a centre-right UK policy think tank, demonstrated that under a “carbon tax plus — per capita — carbon dividend” policy, the poorest citizens would actually be net beneficiaries, given they generate comparatively lower emissions than high earners do.[81] While the transition implies job losses for fossil fuel workers, jobs will be created as new abatement technologies grow (the renewables industry now employs 10 million people globally, a rise of 50% since 2012[82]).

And yet, carbon pricing is by no means sufficient to fully steer the needed decarbonization of all economic sectors (see Figure 18). It is unlikely that the market will solve this challenge alone — unless carbon prices become significantly higher than what is currently being discussed. There are several reasons:

Carbon pricing is typically progressive, but the abatement costs of innovative technologies are not. To support the scale-up phase (for example of electric vehicles), carbon prices therefore do not set an adequate incentive.

Abatement costs differ quite significantly across sectors. This means that carbon prices incentivize some sectors to move earlier than others, while in reality all would need to start moving today to achieve carbon neutrality in 2050.

Sectors also differ in the way their emission reduction measures need to be incentivized over time. A faster shift to electric vehicles needs significant regulatory support today, but much lower incentives going forward, due to strongly declining battery prices. On the other hand, incentives for citizens to isolate their residential buildings and change from fossil fuels to electric heating need to remain very constant over time, given natural renovation and reinvestment cycles.

Carbon prices are unlikely to incentivize the significant investments in new infrastructure that will be required to sustain a low-carbon economy. Given the high pace of the needed transition, there is a risk that the speed of infrastructure transformation will be insufficient.

Finally, some market barriers are not easy for carbon pricing to overcome. For example, appliance efficiency has in the past proven to be more effectively regulated through product standards. Similarly, the “owner-tenant problem” could prevent principally economic investments in the building stock, unless specific instruments can address it.

Figure 18: A carbon price is needed, as are sector-level regulations

Sources: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment; IPCC; IEA; IRENA; interviews conducted by BCG in Q3–4 2019; BCG analysis

Governments therefore need to implement a suite of sector-level regulations to manage the transition efficiently and to enable the full scale and pace of decarbonization that is required.[83] Policy-makers need to factor in financial support for research and the expansion of innovative lowcarbon technologies (such as new processes or materials for steel and cement, hydrogen-based green fuels or CCUS), investments in low-carbon infrastructure (such as charging infrastructure, overhead lines, hydrogen or power transmission) and subsidies for technologies that are still on a learning curve (such as electric vehicles).[84] They must also include incentives for the transition to renewables and/ or nuclear in the power sector, while maintaining sufficient backup capacity for periods with no wind and no sun, as well as the use of rare biomass in the applications where it is most valuable. Ultimately, they likely also need to include standards (e.g. on efficiency) and technology bans (such as on oil and gas heaters) to avoid stranded investments.[85]

Finally, as long as the world as a whole is not moving in unison, ambitious national efforts will necessarily require measures to protect emission-intensive industries from high-carbon, low-cost competition.[86] Especially as technologies to decarbonize industries like steel, chemicals and others are still in the testing stage, this could happen through direct public support (for example via “contracts for difference”). In the medium term, carbon border tax adjustments for the most important products could ensure that carbon price differences between countries and trading blocs are eliminated.

Alternatively, countries can impose “product standards” for high-emission products sold on their territory, for example by imposing a share of zero-carbon steel that needs to be used in the construction or automotive industries. These would transfer the cost burden from industries where this makes a significant relative difference (e.g. steel, cement, plastics) to industries where it does not (e.g. automotive, construction, soda sales). As a report by the Energy Transitions Commission demonstrates, even very high additional costs from low-carbon materials for producers (e.g. +100% for cement) have an almost negligible impact on downstream cost increases for the ultimate consumers (e.g. +3% for a house built with green cement) (see Figure 15 in the previous section).[87]

Such “climate protectionism” measures will be necessary as long as no global level playing field exists, at least on the level of the G20. Ideally, however, these proposed measures are only a means to an end, designed to help realign global policies in line with the Paris Agreement goals that the world community has agreed to pursue.

In parallel, a push for action on the world stage is needed

Many countries can move individually with ambitious national policies that unite emission reductions with economic prosperity and growth. Where national governments are stalling, state, regional or city authorities can make a difference by pushing action locally and through alliances.[88] Nonetheless, climate change is a global problem that ultimately demands a unified, global solution.

It is therefore vital to continue to reinforce multilateral efforts in parallel to unilateral ones. These efforts need to recognize the diverse challenges that countries in different parts of the world are facing and to distribute the financial burden fairly. Multilateral initiatives need to incentivize compliance and disincentivize “free riding” by individual actors. But the more governments move, both on their own and within trading blocs, and the more they make visible progress instead of just committing to ambitious long-term targets without follow-through, the higher the pressure on others becomes to follow suit. After the lack of progress at the COP25 negotiations in Madrid in 2019, COP26 in Glasgow will be a vital test.

5. Individuals need to lead the change as consumers, voters and leaders

Consumers and voters — and public opinion in general — are the ultimate stakeholders of corporations and governments. Without a supportive societal context, corporations are unlikely to perceive the demand from customers and employees to reduce emissions or develop greener products, and governments are unlikely to enact much-needed climate policy and regulations. Conversely, consumer and voter concern about climate change has a strong impact on the way corporations operate. In many Scandinavian countries, for example, a favourable social context and evolving customer behaviours are driving politicians and CEOs to adopt net-zero targets and to develop ambitious strategies that deliver on those targets.

Lifestyle choices can help reduce emissions

Individuals can impact their own emissions through lifestyle choices, and reward companies that provide a “green choice” through their consumption decisions. Everyone can adopt such practices as:

– Low-carbon homes. Better insulation, electric heating, more efficient appliances (especially air conditioning) and a switch to renewable power can enable “zero-carbon living” already today. For example, double-glazing, loft and cavity wall insulation can reduce a semi-detached household’s footprint by up to 20% (2 tonnes of CO2 every year).[89]

– Different mobility habits. By flying less (especially long haul) and switching to e-cars, public transport or bikes, average Westerners can address a significant share of their carbon footprint. One round-trip flight from London to Hong Kong SAR emits 2.9 tonnes of CO2 , as does a half-year of commuting 30 km to and from work in an average internal combustion engine car.[90]

– Sustainable consumption. Changing consumer behaviours in product purchasing (e.g. in fashion, consumables) or services (e.g. sharing economy) can aggregate to affect corporate strategies and business models. Such habits show companies that they can profit from serving their customers more sustainably.

– More sustainable diets. Switching to a plant-based diet would reduce the personal carbon footprint of an average US citizen by more than 40%. Substituting red meat with chicken alone would reduce food-related CO2 emissions by more than 20%.

Individuals can make a difference in organizations and societies

Many emerging stories of progress are the result of entrepreneurial initiative. From CEOs aligning their investors and employees to ambitious net-zero targets, to young leaders forming global protest movements, there are plenty of examples of individuals taking action on climate change and leading the organizations or societies that they are part of.