BMC Health Services Research

Pierre-Yves Brossard, Etienne Minvielle & Claude Sicotte

31 January 2022

datapine

ABSTRACT

Background

As the uptake of health information technologies increased, most healthcare organizations have become producers of big data.

A growing number of hospitals are investing in the development of big data analytics (BDA) capabilities.

If the promises associated with these capabilities are high, how hospitals create value from it remains unclear.

The present study undertakes a scoping review of existing research on BDA use in hospitals to describe the path from BDA capabilities (BDAC) to value and its associated challenges.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted following Arksey and O’Malley’s 5 stages framework. A systematic search strategy was adopted to identify relevant articles in Scopus and Web of Science. Data charting and extraction were performed following an analytical framework that builds on the resource-based view of the firm to describe the path from BDA capabilities to value in hospitals.

Results

Of 1,478 articles identified, 94 were included. Most of them are experimental research ( n=69) published in medical ( n=66) or computer science journals ( n=28).

The main value targets associated with the use of BDA are

- improving the quality of decision-making ( n=56) and

- driving innovation ( n=52)

- which apply mainly to care ( n=67) and

- administrative ( n=48) activities.

To reach these targets, hospitals need to adequately combine BDA capabilities and value creation mechanisms (VCM) to enable knowledge generation and drive its assimilation.

Benefits are endpoints of the value creation process. They are expected in all articles but realized in a few instances only ( n=19).

Conclusions

This review confirms the value creation potential of BDA solutions in hospitals.

It also shows the organizational challenges that prevent hospitals from generating actual benefits from BDAC-building efforts.

The configuring of strategies, technologies and organizational capabilities underlying the development of value-creating BDA solutions should become a priority area for research, with focus on the mechanisms that can drive the alignment of BDA and organizational strategies, and the development of organizational capabilities to support knowledge generation and assimilation.

Background

There is a strong belief that health information technologies (HIT) are essential for improving the performance of health care organizations (HCOs) [ 1].

Convinced by the potential benefits — either clinical, operational or economic — of these new technologies, policy-makers and public agencies in Europe and North America have been committing significant financial resources to accelerate the HIT uptake in HCOs [ 2].

Today, most HCOs use HIT intensively, becoming de facto producers of large volumes of data in digital form.

These digital data come from the different components of local health information systems (HIS), including electronic medical records (EMR) and can be either structured or unstructured [ 3]. These data can be labelled as big data.

As first formalized by Laney [ 4], big data are “high-volume, high-velocity, and/or high-variety information assets that require new forms of processing to enable enhanced decision making, insight discovery, and process optimization”.

This definition is also known as the 3Vs paradigm. The abundance of data confers importance to big data analytics (BDA) that encompass the technologies and techniques that support the processing of these 3Vs [ 5] to derive knowledge that can drive improvements in quality, security and efficiency of care delivery [ 6].

Today, the application of BDA is identified as a key success-factor in health care reforms or transformations [ 7].

In this environment, and as BDA technologies and techniques have become widely available, a growing number of hospitals invest in the development of BDA capabilities (BDAC).

With these investments, hospitals hope to generate knowledge that will help them drive change in their strategies, practices and organizations and better cope with internal and external pressures [ 8].

Hospitals’ investments in BDA are increasing at a rapid pace and are focused on the acquisition and implementation of BDA technologies.

These investments can prove risky and lead to important financial losses if they do not deliver on their promises, especially in an environment exposed to budgetary and organizational constraints like those hospitals are confronted with.

The research question

Our main research question is to understand how value is created from the use of BDA in hospitals.

Answering this question requires to map the path from BDA capabilities to value, gathering evidence on the BDA capabilities that are leveraged, the mechanisms that mediate value creation, the value targets that are pursued and, eventually, the generated benefits. Exploring the path from BDA to value in a diverse set of hospital contexts can help understand challenges hospitals are facing when investing in BDA technologies.

To fill this gap in understanding, we decided to conduct a scoping review, in which we systematically searched, reviewed and analyzed the content of scholar articles covering BDA applications in hospital contexts to propose a comprehensive overview of research on BDA use in hospitals and map the components of the value creation process from BDA.

We opted for a scoping rather than a systematic review because scoping reviews are exploratory in nature [ 12] and particularly relevant to provide a comprehensive overview of the diversity of approaches that characterize a broad topic like the one we study [ 13].

To better deal with the diversity of hospitals’ contexts, strategies, organizations and practices, we followed a descriptive analytical method [ 14] examining all studies in relation to a common analytical framework defining the components of the path from BDA to value. We developed this framework building on the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm [ 15, 16, 17],

By synthesizing the knowledge on how hospitals leverage the BDA capabilities they invest in, our ambition is to help health authorities and hospital managers gain a better understanding of how value is created from big data to better steer their BDA strategies and projects.

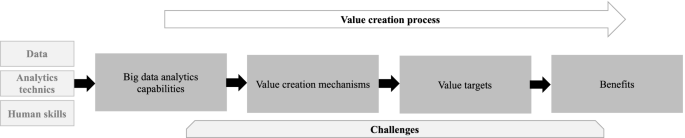

An analytical framework for analyzing the literature

To systematically explore the literature on BDA applications in hospitals, we developed an analytical framework building on the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm [ 15, 16, 17].

RBV is the most frequently used management theory in big data research [ 18].

According to RBV, resources owned by firms are inputs that cannot generate value by themselves [ 16, 17, 19].

Competitive advantage derives from the strategic bundling of valuable resources into capabilities. These capabilities, which are firm-specific constructs and difficult to imitate, will support value creation and competitive advantage.

Hospital managers are currently investing in data assets, analytics technologies and techniques, and human skills to develop the infrastructure on which to develop BDA capabilities [ 20].

These capabilities are essential to manage the volume, variety and velocity of available data and to generate valuable results from their analysis [ 21].

A challenge for hospital managers is to select which bundling strategies to operate in order to develop the capabilities that will deliver valuable outputs [ 22, 23] and justify the investments made.

Based on the work by Wang and Hajli [ 24], the main BDA capabilities to support value creation in healthcare are:

a) traceability,

b) interoperability

c) analytical capability,

d) predictive capability,

e) decision support capability.

According to the RBV theory, once developed, these capabilities can support multiple value-creating needs for hospitals.

This study expands the RBV to question how BDA capabilities support value creation and for what benefits. The exploration of the value creation process from BDA capabilities starts with the mechanisms which mediate the link between BDAC and value. These value creation mechanisms (VCM) are sources of value but not value themselves as it is sometimes mistaken in the literature [ 10, 25]. It is important to reposition VCMs in the debate for what they are: Enablers of value creation and organizational transformation. Building on existing literature [ 25], we identified and adapted to the hospital context five value creation mechanisms: creating process and outcomes transparency, enabling discovery and experimentation, supporting customization of actions through segmentation, enabling optimization through prediction, and enabling real time monitoring of activities and outcomes [ 25, 26].

These mechanisms are expected to enhance hospital professionals’ abilities to drive change in their practices and organizations. Looking into the selected literature, the review describes what are the value targets set by hospital professionals.

Eventually, reaching these targets can generate benefits for hospitals.

We distinguished expected and measured benefits based on a classification adapted from the framework developed by Shang and Seddon [ 27] which defines 4 types of benefits:

- operational,

- organizational,

- managerial and

- strategic.

By applying the framework summarized in Fig. 1 to review the literature on BDA applications in hospitals, we aim at shedding a light into the black box between BDAC and value.

If RBV asserts that capabilities are essential to support value creation, a better understanding of how these capabilities are realized is needed.

Methods

See the original publication

We will answer it by investigating a set of secondary questions related to the different components of our analytical framework:

- What are the BDAC leveraged by hospitals to create value?

- What are the mechanisms that mediate the link between capabilities and value?

- What are the value targets and benefits?

- What are the challenges associated with value creation from BDAC?

Results

Our findings are presented in the next sections. We first describe the study characteristics (1) before exploring more thoroughly the value creation process from BDAC (2) and its associated challenges (3).

Study characteristics

Big data analytics emerged in the healthcare research literature in 2008 with the volume of articles exploding in 2014 [ 9].

With 95% of articles published between 2014 and 2019 our initial search results (1,478 articles) are aligned with this trend. This dynamic is also confirmed in our final dataset with 57 of 94 articles being published in 2018 and 2019.

Most articles are experimental ( n=69). They are proofs of concepts of different BDA functionalities and techniques to deal with hospital-specific clinical or administrative challenges. They cover both theoretical and practical contributions. Twenty two articles are case studies investigating the realization of BDA capabilities in hospitals, or groups of hospitals, that position themselves as early-adopters of these new technologies [ 30].

Using the All-Science Journal Classification (ASJC), we categorized the selected articles by research fields. Medicine and computer science are associated respectively with 66 and 28 articles. Other fields are engineering ( n=9), nursing ( n=6), decision science ( n=6). Business and management are marginal, accounting for only 4 articles.

The summary of study articles and the description of the path-to-value from BDAC are presented in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 in Appendix.

Value creation process from BDA capabilities

Big data analytics capabilities

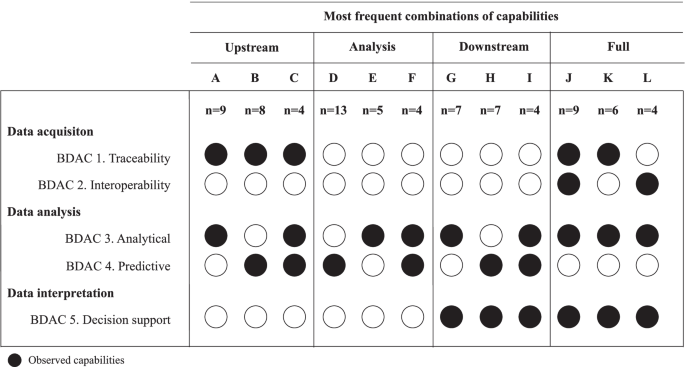

The 5 types of capabilities we classified are associated with the 3 main steps of the BDA process [ 31]:

- data acquisition,

- data analysis and

- data interpretation.

Data acquisition (n=54)

Traceability and interoperability are two types of BDAC associated with this first step of the BDA process. They are respectively mentioned in 43 and 28 articles.

Interoperability is essential to aggregate data from multiple sources and locations and to integrate them into a single data structure [ 6]. This capability is essential to support the constitution of databases from different sources [ 35] and the linking of databases from different parts of the HIS [ 36, 37].

Data analysis (n=94)

Analytical capability and predictive capabilities are both focused on data analysis.

Analytical capability is the most frequently mentioned capability in our research ( n=58).

It is the ability to use descriptive data analytics techniques such as data mining, text mining and statistics to generate new knowledge. For example, natural language processing techniques can help automate the extraction of disease-specific risk factors from unstructured data [ 38] or explore patients’ verbal complaints to identify text patterns that can be further analyzed to be associated with specific conditions [ 39]. The use of advanced statistics enables to describe population characteristics [ 40], characterize the features of a condition [ 41] or identify correlation between two dimensions such as staffing level and clinical outcomes [ 42].

Interpretation

To acquire, analyze and interpret data, the literature indicates that hospitals do not rely on a single capability but on combinations. 28 articles present combinations of capabilities that are focused on the upstream part of the big data analytics process (data acquisition and data analysis), 18 on the downstream part (data analysis and data interpretation) and 26 on the full process (data acquisition, data analysis and data interpretation). In Figure 3, we present the most frequent combinations of capabilities and their frequency.

Value creation mechanisms

As value creation mechanisms were not explicitly identified in the selected articles, we deducted them following existing classifications developed by Manyika [ 26].

Creating process and outcomes transparency (VCM1) is identified in 42 articles.

It is a fundamental source of value from BDA for hospitals which can gain complete and consistent visibility on processes and outcomes.

Process transparency ( n=17) enables change in practices and organizations.

For example, the adoption of a comprehensive data analytics platform enables clinical and administrative staffs to better identify variations in clinical outcomes, supplies, labor and costs and support the redefinition of practices and organizations for operational gains [ 48].

Outcomes transparency ( n=25) can support quality improvement initiatives.

For example, BDA can facilitate the development of risk-adjusted quality assessment models that can be applied to benchmark performance between services, institutions or healthcare systems and act as a driver of change [ 32].

Enabling optimization through prediction can mediate value creation (VCM4). The ability to determine the best path from the use of BDA appeared in 19 articles.

Data-driven determination of probabilistic outcomes paves the way for prescriptive analytics whose ambition is to prescribe action plans to increase the likelihood of the occurrence of a desired outcome [ 6].

For example, by outperforming human judgement in the prediction of patient flow, statistical models can contribute to recommend optimized resource allocation strategies to avoid wastage and unnecessary spending [ 54].

Enabling real time monitoring of activities and outcomes (VCM5) is mentioned in 25 articles.

Monitoring patients or activities come with a heavy burden of information processing that is time consuming for resource-restrained hospitals.

BDA applications not only unload staff members from these activities, but offer the opportunity to increase the volume and the depth of data sources to monitor.

Activities which would normally be beyond human capacity such as real-time monitoring of drug-drug interactions [ 33] or monitoring health status of neonatal patients from devices-generated data [ 55] are made possible by BDA applications to enable responsiveness.

It is interesting to note that these five mechanisms are different in nature.

With transparency, value comes with the availability. With discovery, it comes from the content. With segmentation, prediction and monitoring, the value comes from the format.

In many instances, these value creation mechanisms need to be combined to put knowledge into actions.

Analyzing the combinations confirms discovery as being the cornerstone of value creation from BDAC as it appears in the three most commonly observed combinations

a) VCM2-VCM3 [ 46],

b) VCM1-VCM2 ( n=41) and

c) VCM2-VCM5 [ 23].

These combination are associated with different logics. The association of discovery and transparency is focused on knowledge generation. It enables hospitals to increase their knowledge stock that can later be transferred to practice and decision-making settings. It is an exploratory approach to value creation from BDAC with the ambition being to find change opportunities and define targets. The combinations of discovery and segmentation or monitoring are focused on knowledge assimilation. The objective is to make knowledge applicable to drive changes in practices and organizations. It is an operational approach to value creation from BDAC. The targets to reach are known and BDA is leveraged to support practical changes required to reach them.

Value targets

BDA is a versatile technology that can apply to hospitals’ main activity domains which are

- care ( n=67),

- administration ( n=48) and

- research ( n=8).

In each of these domains, a variety of value targets can be set and reached. These targets differ in nature and serve a wide range of objectives.

We identify 3 targets:

- improving quality of decision-making (VT1),

- driving innovation (VT2) and

- improving process performance (VT3).

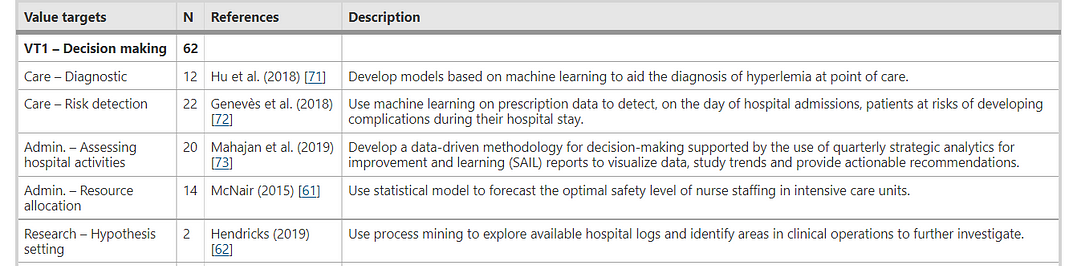

Improving the quality of decision-making (VT1) is the most frequent value target pursued in the literature ( n=62).

The ability to generate and disseminate knowledge from available data coupled with incentives to act on these data or developing tools to augment human capability can enable improvement of decision-making.

In care, BDA applications can facilitate disease diagnosis ( n=12) and risk detection ( n=22) by accelerating the decision-making process or improving its precision.

- For example, BDA can enable the development of a personalized diagnostic model [ 56]

- or support the design of rapid diagnosis at point of care [ 57].

- BDA techniques can also enable the identification of patients at risks of complications after surgery [ 43] or at risks of readmission after inpatient stays [ 58].

By enabling outcomes and process transparency, BDA can support administrative teams in assessing hospital activities ( n=20).

- It can enable managers to gain visibility on the quality of care [ 32],

- assess performance of new organizations [ 59] and

- engage in consensus-building with clinical teams to drive operational changes [ 48].

BDA can also contribute to improving decision-making on resource allocation ( n=14).

Predictive analytics solutions can support optimization of hospital wards usage and management [ 45] or predict patient volumes to adapt staffing levels [ 60] or optimize safety stock of nurses staffing [ 61].

Regarding research activities, BDA can facilitate hypothesis-setting ( n=2) with BDA tools enabling researcher in preliminary investigation to test the relevance of their research question or identify new research opportunities [ 62, 63].

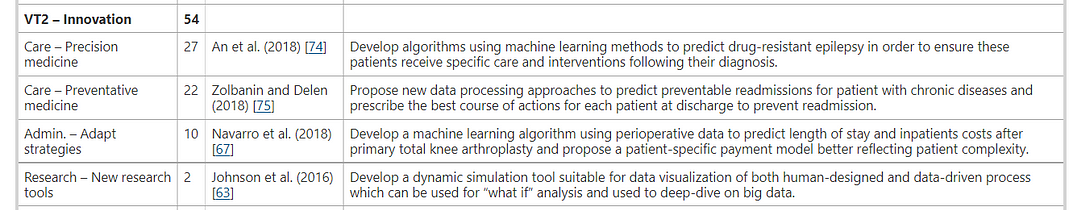

The second value target is driving innovation (VT2)

It appears in 54 articles. By analyzing new insights, hospitals’ clinical, administrative and research staffs can better identify opportunities for innovation that will drive changes in their practices and organizations.

In care, the two main types of innovation pursued are precision medicine, which consists in personalizing care for better outcomes ( n=27), and preventative medicine ( n=22), which consists in changing the course of actions to avoid the occurrence of adverse events.

BDA can support the emergence of precision medicine by enabling physicians to identify patients who will benefit more from specific therapies [ 64] or to predict prognosis to adapt the course of treatment [ 41].

BDA can create the conditions for innovative approach to risk management in care by enabling the identification of patients at risks of surgical complications ahead of intervention [ 65] or at risks of pressure ulcer during inpatient stays [ 66].

For managers, BDA can be used as a tool to adapt strategies ( n=10).

It can support the design of new payment models for patient subgroups by predicting costs of care [ 67].

The interest of these models is two-fold: secure operational margin and cost control and revenue level, and impact competitors that will need to adapt to new delivery and financing schemes.

For research teams ( n=2), BDA can enable the development of innovative tools to support the emergence of new clinical trial designs and facilitate the identification of patient selection for recruitment [ 68], contributing to reinforcing the competitiveness of research activities.

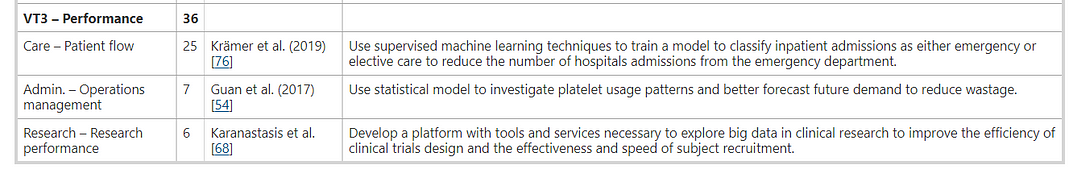

The last value target we identified is performance improvement (VT3)

Enabling process transparency and facilitating continuous monitoring of activities can contribute to process improvement all along the hospital value chains ( n=36).

Optimization of patient flow in care units is a common value target in care ( n=25) as BDA can support patient waiting-time reduction by optimizing scheduling [ 45], or improve inpatient capacity usage through continuous prediction of inpatients length of stays [ 67].

This also applies to research ( n=6), where the use of BDA has considerably

- facilitated patient screening and

- selection to perform retrospective studies [ 68].

BDA applications and their value targets are presented in Table 2.

See the original publication

Table 2 Distribution by value targets

Benefits

Hospital professionals associate benefit expectations with the definition and pursuit of value targets. These benefits are detailed in the Supplementary Table 4 in Appendix.

The benefits that are the most frequently expected are operational ( n=83).

BDA is expected to help improve the quality of clinical decisions ( n=34) [ 39, 45, 57, 77] and outcomes ( n=27) [ 37, 53, 54, 58, 61, 78].

It is also expected to enable cost-reduction ( n=38) by reducing unnecessary care [ 41, 56, 64, 79, 80, 81] and admissions [ 58, 82, 83]; productivity gains ( n=26) by optimizing resource usage in care and administrative units [ 32, 84, 85];

or service improvement ( n=27) by providing healthcare professionals new operational tools to support their practices [ 44, 82].

Organizational benefits are expected from BDA in 62 articles.

These changes are observed in individual practices (it may be diagnosis, prescription, orientation) [ 34, 86] with BDA acting as an enabler of learning and skills development ( n=21).

It can also support changes in work patterns to drive new care organizations (coordination, pathways, access to technical resources) ( n=41) [ 67, 76, 87].

Finally, BDA can enable better communication and collaboration to change ways of working (collectively, cross-functionally) ( n=17) [ 63, 75].

Finally, the contribution of BDA to managerial and strategic benefits are expected in respectively 52 and 26 articles.

The optimization of resource management [ 44, 54, 69, 88] is the main managerial impact considered in the reviewed articles ( n=31),

followed by performance improvement ( n=22) [ 30, 48, 89]

and improved decision-making ( n=18) [ 90, 91, 92].

As for strategic benefits, the main feature is differentiate hospitals from other healthcare organizations ( n=12) as mentioned by Ramkumar [ 79], Karanastasis [ 68] and McNair [ 61].

BDA can also be leveraged to support business innovation ( n=9), which translates into the capacity to offer new value propositions to internal or external stakeholders, by either financing [ 79, 93], or way of working [ 30].

Improved strategic positioning ( n=7) is another feature. It can take the form of increased attractiveness of care resources [ 30, 61] or reinforced influence over internal and external stakeholders [ 66, 89, 94].

If expectations are numerous, measured benefits are scarce.

Only 19 articles quantify or describe benefits of BDA applications. This observation is not surprising given the experimental nature of the literature reviewed.

Most of the measured benefits are operational ( n=13) with

- cost-reduction being monitored in 6 articles [ 30, 48, 53, 59, 79, 82],

- quality improvements [ 47, 79, 95, 96] and service improvement in 4 articles each [ 79, 85, 97, 98] and

- productivity gains in 2 articles [ 95, 99].

Organizational benefits are assessed in 6 articles with focus on changing work patterns ( n=4) [ 63, 90, 96, 99] and improving communication and collaboration ( n=3) [ 79, 86, 96].

Finally, managerial and strategic benefits appeared, respectively, in 6 and 4 articles.

The limited focus on managerial and strategic impact is coherent with the nature of the literature reviewed.

Most articles in our datasets discuss BDA applications at a micro level, hence setting their focus on micro benefits that translate into operational and organizational perspectives.

Challenges to value creation

Many challenges hinder the value creation process described in the previous sections.

These challenges impact

- the generation of valuable knowledge ( n=79),

- the transformation of knowledge into actions ( n=42), and

- eventually the ability to the develop a BDA strategy ( n=21).

Generation of valuable knowledge

Developing BDAC to generate valuable knowledge require to properly orchestrate data, technologies and human resources.

Data-related challenges are the main source of concerns in selected articles. As obvious as it may sound, the generation of valuable knowledge from BDAC start with data access and quality.

Access challenge to data sources is mentioned in 48 articles. Access issues are observed between institutions [ 54, 58], different units in the same organizations [ 83] and different IT components [ 52].

They can be caused by organizational complexity [ 99], limited incentives to share data [ 99] or a lack of shared standards [ 42].

Data quality is mentioned 33 times with veracity of data being in question.

Veracity is defined as “uncertainty due to data inconsistency and incompleteness, ambiguities, latency, deception, model approximations” [ 100].

Inconsistencies are caused by data collection systems and processes that are different from one site to the other [ 54], inconsistent use of medical terminology [ 49], and variance in coding practices between sites or within teams [ 50, 101].

Most datasets are incomplete [ 102] with missing variables [ 32, 103, 104] and values [ 105, 106] or underreporting of certain conditions [ 66].

Capitalizing on BDA infrastructures, also requires hospitals to develop multi-disciplinary teams [ 38] associating technological experts and clinicians.

Engaging with clinical teams in BDA projects often proves challenging as finding the right level of engagement to build trust [ 37] is made difficult by the heavy workload required [ 50] and the limited time these professionals can dedicate to such initiatives [ 94].

Hospital teams are also dealing with methodological challenges ( n=16).

When hospitals manage to create knowledge, the value of this knowledge is put in doubt.

The validity of models is often in question and needs to be demonstrated before generalization [ 79].

Knowledge generated from the use of retrospective data would need to be confirmed with prospective studies [ 47, 76].

Experiments performed on a single site expose models and results to the influence of the context of experiment and introduce variability and hinder their reproducibility [ 99].

Solutions should be tested on multiple datasets to ensure a similar level of performance can be achieved at independent sites [ 108] which is a prerequisite to portability, adaptability and economic viability of BDA models [ 43, 84].

Finally, the lack of talents, or inability to engage them in data analysis activities restricts the ability to create valuable insights ( n=17).

Many organizations are facing difficulties to attract data scientists [ 30] and, as a consequence, lack the necessary skills to properly analyze and exploit data [ 81].

Developing BDA solutions to generate knowledge requires bringing clinical and technical expertise together.

Setting up these multidisciplinary teams is complex [ 48] as it is often difficult to engage clinical experts in these activities [ 37] because that would result in a heavy workload for professionals who already have limited availability [ 50, 94].

Transforming knowledge into actions

Knowledge generation from BDA can trigger in-depth changes that can eventually contribute to the reconfiguration of hospitals’ organizational capabilities [ 30].

Despite the strong technological advances in leading hospitals, there still is a considerable gap between BDA expectations in the healthcare field, and the benefits actually realized on the ground [ 109].

This gap can be explained by the complexity of BDA solutions ( n=19).

Developing BDA solutions expose hospitals to a set of organizational challenges among which is the ability to produce intensive cross-organization efforts to develop and implement BDA projects [ 68].

The complexity of these projects requires time and budget [ 63].

It is a long-term process that goes beyond the initial phase of knowledge generation [ 95].

It requires change management efforts with the conception of integrated package to drive change efficiently [ 82].

For hospitals investing in BDA, acceptance of BDA solutions is a major challenge ( n=33) as one of the main risks is to see professionals walk away from these new technologies.

Discontent starts with the perception of BD as a burden, with data collection being often considered as a tedious task [ 32].

The results generated often lack interpretability [ 41] with a growing number of algorithms being designed as black boxes [ 97, 101].

Lack of transparency negatively impacts trust of practitioners in models [ 77].

Usability of solution is another major challenge [ 44] underlining the importance of participatory design.

Hospitals need to create an enabling infrastructure [ 86] to improve acceptance.

It requires to be transparent on the limitations of these technologies [ 51, 103], to train and educate clinicians on BDA [ 86, 95], involve them in the design of solutions [ 55] and ensure they understand the gains [ 110]. Change teams should be considered to engage in peer learning [ 86] and educate staffs on changes induced by BDA [ 48].

Challenges for hospital to invest in BDA strategies

The main challenge for hospitals investing in BDA strategies is to balance costs and benefits of BDA implementation and use [ 35].

A set of economic challenges ( n=13) question the viability of BDA investments.

The development of a BDA platform [ 68], the integration of data sources [ 37], their maintenance [ 95] and their analysis [ 87] are all heavy direct costs.

Indirect costs can also be very significant as professionals need to invest time in solution development, which impacts clinical resources usage, and consequently, activity level and revenues [ 68].

If the costs are well defined, the benefits of investing in BDA are unclear and need to be assessed [ 89].

Our research sample underlines the difficulty to measure the impacts generated by the use of BDA.

As such, calculating the ROI is only possible a posteriori, letting hospitals confronted with uncertainty.

If hospitals are expected to invest in BDA, few incentive programs reward the use of BDA solutions financially [ 30]. There is a strong need for advocacy and lobbying to build political partnerships to adopt new approaches and support the emergence of incentives [ 79].

Discussion

In our scoping review, we aimed to explore how value is created from the use of BDA in hospitals.

We found that if the use of BDA in hospitals has gained interest in the research community, most of the work done on the subject is technology-focused and has as main goals to demonstrate the relevance of BDA to solve medical or organizational challenges in hospitals, or the feasibility and validity of BDA solutions.

Apart from a handful of references, value creation is approached as a by-product of BDA-driven knowledge generation and not a primary research objective.

From our review, there is evidence on the versatility of BDA to create value for hospitals.

BDA can contribute to reach a large scope of value targets in all of hospital activity domains, and it can do so in a myriad of ways.

We observe that value creation from BDA relies on a combinatory approach of resources, capabilities and mechanisms.

BDAC are developed from the combination of data assets, technologies, techniques and skills, while knowledge is generated from the combination of BDACs.

Hospital managers are facing countless possibilities to approach knowledge generation and address value-creating needs.

Their challenge is to properly orchestrate resources to develop a set of BDACs that can support the right value creation mechanisms, with the objective of turning these capabilities into core competencies [ 111] which will eventually drive value creation and competitive advantage.

These outlooks on the value creation potential of BDA are particularly interesting as hospitals are exposed to internal and external pressures from regulatory changes, innovation or professional dynamics to which they need to adapt [ 112].

However, expectations regarding the realization of benefits from the use of BDA [ 6, 113] are far from being reflected in the literature.

We observe a significant gap between the value creation potential of BDA solutions in hospital and their actual impacts. Evidence on the difficulties to realize value from investments made in BDAC building can be found applying the RBV’s Value-Rarity-Imitability-Organization (VRIO) framework [ 114].

There is no doubt that BDAC are valuable, rare and difficult to imitate.

They are valuable as they enable hospitals to generate knowledge that can meet value creating needs.

They are rare as data resources are, in most cases, hospital-specific [ 34], as skills are difficult to aggregate [ 30, 38, 92] and results generated from BDA solutions are often non-generalizable [ 44, 56, 115] from one context to the other.

Finally, they are difficult to imitate as they are path-dependent, relying on previous HIT investments [ 51] and data collection practices, and socially complex as they cannot be managed in a systematic way [ 48] with each hospital leveraging its BDAC to adapt a specific context.

However, in most articles reviewed, BDAC lack organizational embeddedness which is the fourth dimension of the VRIO framework.

This lack of organizational embeddedness is observed at different levels. At the micro level, BDAC are dependent on individual practices.

The generation of valuable knowledge can be hindered by poor data collection practices [ 66, 101] and inconsistent use of medical terminologies [ 49].

At the meso level, the lack of budget dedicated to BDA initiatives [ 68, 81], of change management to promote the cross-functional efforts needed [ 30, 86], of data culture in the organization [ 48, 95], can negatively impact the ability to develop BDAC, the value of the knowledge generated from BDAC or the acceptance and assimilation of this knowledge [ 36].

Finally, at the macro level, the lack of incentives to share data or invest in BDAC [ 42, 99] and the lack of institutional recognition of BDA-generated knowledge can factor in the realization of expected benefits.

These organizational factors are as many weak links that can derail the value creation process from BDAC despite significant investments. It underlines that if BDAC can be valuable sources of knowledge, they cannot create value in isolation. They need to be combined harmoniously with other resources and capabilities to realize their potential and deliver on the value proposition hospitals are investing in [ 114, 116, 117].

While most of current research on BDA in hospitals is tactical, focusing on technological and technical dimensions and on narrow applications of BDA solutions, it appears essential to draw the attention of researchers and practitioners on strategic challenges.

The debate should not stay on the potential of BDA applications and their ability to generate knowledge, but on how hospitals should get organized to acquire, process and use knowledge generated from BDAC while minimizing the weak links in the value creation process.

The strategic challenges faced by hospitals are twofold:

- they need to align their BDA strategy with hospitals’ long term views,

- they need to adapt their organizational capabilities to be able to move along the value creation process.

From an alignment perspective, if the development and implementation of BDAC is IT-oriented, given the costs and complexity of the operation, hospitals BDA strategy must be aligned with the institutions’ strategy and must be integrated in it.

Managers need to combine mechanisms to drive this alignment.

These mechanisms can be, among others, governance, procedures, data cultures.

From an organizational perspective, hospitals need to develop the capabilities that will enable them to explore knowledge generation opportunities, recognize relevant knowledge and assimilate it into their processes to generate impacts.

The organization has to be able to articulate knowledge generation and assimilation.

The challenge for hospital managers is to define a context in which knowledge generation meet the objectives of the organization. This perspective is not covered in the existing literature.

Empirical studies on how hospitals align their BDA and organizational strategies, and develop their organizational capabilities to create value are needed.

Given the characteristics of BDA, the goal of hospitals professionals should be to generate impact from BDAC while minimizing the costs of development and appropriation.

Strengths and limitations

See the original publication.

Conclusion

This scoping review is the first study that explores how value is created from BDA in hospitals. Its contribution is twofold.

On the one hand, it confirms the versatility and value creation potential of BDA capabilities in hospital. Articles reviewed demonstrate the technological feasibility of BDA-driven knowledge generation solutions that can address value creation needs in all of hospitals’ main activity domains.

On the other hand, it points at a glaring gap between the value creation potential of BDA solutions and their actual impacts. Availability of BDA capabilities and BDA-generated knowledge are necessary and yet insufficient conditions for value creation.

In many cases, BDA capabilities are built independently of organizational characteristics and goals and are unable to trigger the value creation mechanisms that will enable hospitals move along the path-to-value.

The configuring of strategies, technologies and organizational capabilities around which the movement towards value realization is orchestrated should become a priority area for research.

In that sense, we encourage future empirical work on the mechanisms that can drive the alignment of BDA and organizational strategies, and on the development of organizational capabilities required to support knowledge generation and assimilation in ways that support the realization of BDA potential.

We hope this review will encourage hospital professionals to reflect upon the factors needed to develop BDA strategies and that our analytical framework will be the basis of a practical tool to explore facilitators and barriers in the development of BDA in hospitals.

Availability of data and materials

See the original publication

Author information

- Arènes (CNRS UMR 6051), Institut du Management, Chaire Prospective en Santé, École des Hautes Études en Santé Publique, Rennes, France

Pierre-Yves Brossard & Claude Sicotte - i3-Centre de Recherche en Gestion, Institut Interdisciplinaire de l’Innovation (UMR 9217), École polytechnique, Palaiseau, France

Etienne Minvielle - Institut Gustave Roussy, Patient Pathway Department, Villejuif, France

Etienne Minvielle - Department of Health Management, Evaluation and Policy, University of

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Claude Sicotte

References

See the original publication

Originally published at https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com on January 31, 2022.