HealthSystems — transformation institute

Joaquim Cardoso MSc*

Chief Researcher, Editor and Strategy Officer (CSO)

November 16, 2022

*MSc from London Business School — MIT Sloan Masters Program

Source: Alzheimer’s & Dementia — Diagnosis,Assessment &DiseaseMonitoring, Wyllians Vendramini Borelli MD et al

What is the message?

- The prevalence of SCD in Brazil was 29.21% (28.22%–30.21%), varying according to region, sex, and age.

- The prevalence of SCD in Brazil is higher than in high-income countries

- SCD was strongly associated with hearing loss, low education, psychological distress, Brown/Pardo and Black races.

- Hearing loss complaint was the most robust factor associated with SCD.

What are the recommendations?

- Public strategies that target SCD may help mitigate the incidence of dementia.

Infographic

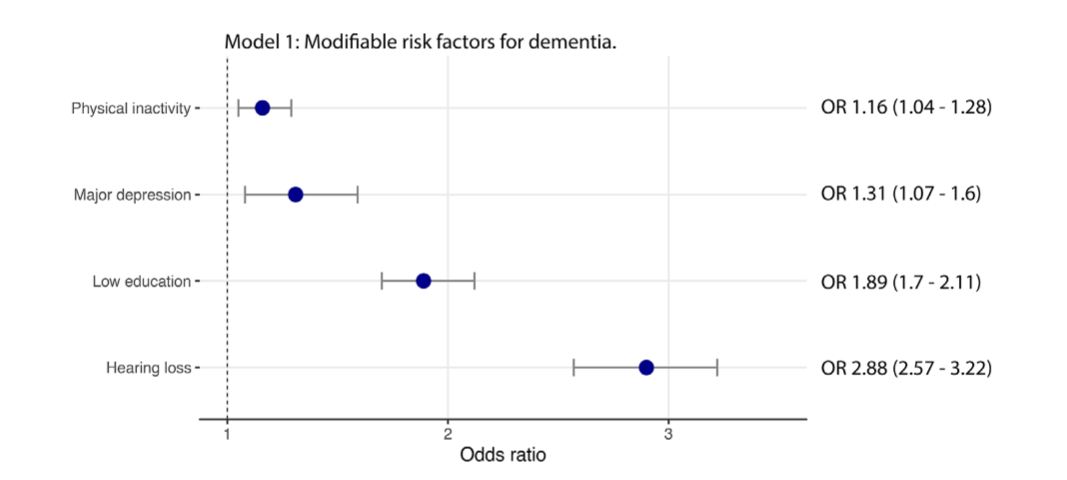

FIGURE 3 Odds ratio of identified riskfactors associated with subjective cognitive decline in this sample.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (excerpt version)

Subjective cognitive decline in Brazil: Prevalence and association with dementia modifiable risk factors in a population-based study

Alzheimer’s & Dementia (AAIC)

Wyllians Vendramini Borelli MD, PhD,Eduardo R. Zimmer PhD,Andrei Bieger BSc,Bruna Coelho,Tharick A. Pascoal MD, PhD,Márcia Lorena Fagundes Chaves MD, PhD,Rebecca Amariglio PhD,Raphael Machado Castilhos MD, PhD

14 November 2022

Abstract

Introduction

- Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) may be an early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease.

- We aimed to estimate the prevalence of SCD in Brazil and its association with dementia modifiable risk factors.

Methods

- We used data of 8138 participants from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil), a population-based study that included clinical and demographic variables of individuals across the country.

- We calculated the prevalence of SCD and its association with dementia modifiable risk factors.

Results

- We found that the prevalence of SCD in Brazil was 29.21% (28.22%–30.21%), varying according to region, sex, and age.

- SCD was strongly associated with hearing loss, low education, psychological distress, Brown/Pardo and Black races.

We found that the prevalence of SCD in Brazil was 29.21% (28.22%–30.21%), varying according to region, sex, and age.

SCD was strongly associated with hearing loss, low education, psychological distress, Brown/Pardo and Black races.

Discussion

- The prevalence of SCD in Brazil is higher than in high-income countries.

- Brown/Black races and dementia modifiable risk factors were associated with SCD.

- Public strategies that target SCD may help mitigate the incidence of dementia.

The prevalence of SCD in Brazil is higher than in high-income countries. Brown/Black races and dementia modifiable risk factors were associated with SCD.

Public strategies that target SCD may help mitigate the incidence of dementia.

1 BACKGROUND

Because life expectancy is increasing worldwide, a growing number of older individuals presenting cognitive decline is expected in the coming decades.

By 2050, the global estimate of dementia is ∼150 million cases.1

Among the strategies to mitigate the social and economic burden associated with dementia, the identification of the earliest manifestations of cognitive syndromes is essential.2

Modifiable risk factors of dementia should be prioritized in individuals with the earliest signs of cognitive decline, such as hearing loss and physical inactivity.3

In this context, the construct of subjective cognitive decline (SCD) has been shown to be useful in identifying individuals at greater risk of cognitive decline, especially in the context of the Alzheimer’s disease continuum.4, 5

SCD is usually defined as a self-reported cognitive complaint in persons with normal cognition, and it has been suggested as a predictor of dementia.6

In addition, SCD appears to be associated with a broader risk of dementia.7

Thus identifying individuals with SCD may help target preventable risk factors for dementia and guide the decisions of policymakers in public health.8

A recent meta-analysis indicates that the prevalence of SCD varies from 5% to 58% according to age, sociocultural background, and the criteria used.9

Most of these estimations come from studies conducted in high-income countries — especially Europe and North America — whereas, paradoxically, two-thirds of all individuals with dementia live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).10

Although many of the modifiable risk factors for dementia are frequent in LMIC populations, such as low education and higher cardiovascular burden,11 the frequency of these risk factors in SCD is still poorly understood.

One study identified that older age, thyroid disease, and minimal anxiety symptoms among others are risk factors of SCD, but the prevalence of well-known risk factors of dementia in SCD remains unclear.12

Determining the profile and risk factors for SCD in the Brazilian population is both crucial and difficult for several reasons.

First, Brazil is the largest Latin American country with more than 30 million older adults.13

Second, it is a multicultural nation, composed of a myriad of racial groups.

Third, Brazil has high rates of low education and unequal access to medical care.14

Finally, Brazil is globally known for its unified health care system (Sistema Único de Saúde [SUS]), which provides an opportunity to study and organize public health strategies.

Herein, we aimed at investigating the prevalence of SCD individuals in Brazil and its associated risk factors.

To this end, we obtained data from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil),15 a nationwide epidemiological taskforce.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

- Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional sources, meetings, and presentations. We did not find any study that evaluated the prevalence of subjective cognitive decline (SCD) and its associated risk factors in Brazil or even in Latin America.

- Interpretation: Our findings are higher than the prevalence found in studies from high-income countries. Hearing loss, psychological distress, and Brown/Pardo and Black races are strongly associated with SCD.

- Future directions: The identification of individuals with SCD and knowing of its risk factors can lead to the elaboration of public health strategies aimed at reducing the impact of modifiable risk factors for dementia. Our findings may also help to understand the social and racial inequalities regarding the early diagnosis of dementia.

2 METHODS (and other sections)

See the original publication (this is an excerpt version only)

3 RESULTS

We included 8138 Individuals from the ELSI-Brazil cohort in the final analysis with a mean age of 62.6 (± 9.4) years, 56% female, and mean education of 5.6 (± 4.3) years.

The subsample excluded by the incomplete responses (n = 1274) had demographic and clinical characteristics that were similar to those of the whole sample (Table S5).

In addition, the sensitive analysis showed that this subsample was similarly associated with the independent variables (Table S6).

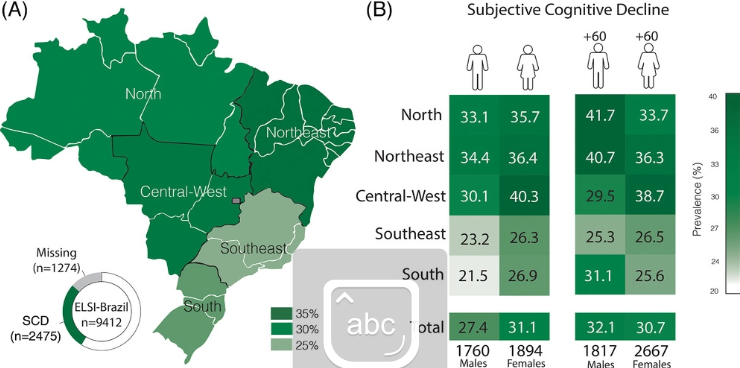

Overall prevalence of SCD was 29.21% (95% confidence interval [CI] 28.22% to 30.21%), and this prevalence varied according to age, sex, and region (Figure 2 and Table S7).

From all individuals that met the study criteria, 2475 were classified as SCD (Table 1), and those without memory complaint (4212) were classified as CU.

Compared with CU individuals, those with SCD presented a higher frequency of female individuals, lower family income, and increased frequency of Black individuals.

FIGURE 2

(A) Prevalence of subjective cognitive decline (SCD) according to each Brazilian region. (B) Prevalence of subjective cognitive decline (SCD) according to age and sex in each Brazilian region

TABLE 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample, divided between cognitively unimpaired (CU) and subjective cognitive decline (SCD) subjects

CU (n = 4212)SCD (n = 2475)Age (years)62.4 (± 9.4)62.7 (± 9.3)Sex (F)2102 (49.9%)1408 (56.9%)Education (years)6.3 (± 4.5)4.8 (± 3.9)Illiterate914 (21.7%)753 (30.5%)Family income5.1 (± 3.7)4.2 (± 2.7)Race/color skinWhite1739 (42.7%)824 (34.3%)Black375 (9.2%)256 (10.7%)Brown/Pardo1821 (44.8%)1247 (52.0%)Asian40 (1.0%)18 (0.8%)Indigenous94 (2.3%)54 (2.3%)Urban zone3627 (86.1%)2027 (81.9%)

The frequency of well-known risk factors for dementia was different between groups (Table 2).

Compared with the CU, the SCD group showed increased rates of low education, with a higher percentage of illiterates and higher frequency of physically inactive individuals (p < 0.001 for both).

Frequency of hearing loss was substantially higher in SCD (p < 0.0001), but the frequency of hearing aids use was similar to among CU individuals (p > 0.05).

The SCD group also presented increased psychological distress, specifically higher symptoms of depression and frequent feeling of loneliness (p < 0.0001).

Sleep quality was also worse in SCD when compared with CU (p < 0.001).

Regarding sex-specific differences, men with SCD showed increased frequency of hearing loss, heavy drinking, active smoking, but women with SCD had a higher frequency of hypertension, obesity, depression, and physical inactivity (Table S8).

TABLE 2. Modifiable risk factors for dementia, and clinical and mental health conditions of the sample

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify the association between well-known modifiable risk factors for dementia and SCD (Figure 3).

- Low education (odds ratio [OR] 1.9, 95% CI 1.7 to 2.1),

- hearing loss (OR 2.9, 95% CI 2.6 to 3.2),

- depression (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.6), and

- physical inactivity (OR 1.2, 95% CI 1 to 1.3) were significant predictors of SCD.

A second regression model (Model 2) accounted for variables that presented statistically significant in univariate analysis (Table 2).

This model revealed that hearing loss was the strongest predictor of SCD, while low education, female, poor sleep quality, and frequent feeling of loneliness were also predictors (Figure 3).

Black and Brown/Pardo races presented increased odds (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.7 and OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.6, respectively) of SCD compared to White individuals (OR 1, reference).

Odds ratio of identified risk factors associated with subjective cognitive decline in this sample. Model 1: established modifiable risk factors for dementia. Model 2: univariate-based analysis of variables included in the study

4 DISCUSSION

This study provides epidemiological estimates of SCD in a continental-sized country.

As a large LMIC with very low education attainment, Brazil’s population shares many similarities with most older adults living with cognitive decline around the globe.11

These findings may support strategies applicable in public health systems in LMICs worldwide, with focus on modifiable risk factors for dementia in individuals with SCD.

Our findings might guide multidomain lifestyle-intervention studies to control risk factors for dementia, such as clinical trials focused on dementia prevention.23

Herein we used the most recent definition of SCD,6 which is characterized by consistent cognitive complaints in cognitively normal individuals.

We found an estimated prevalence of SCD of 29.21% among Brazilian older adults, with variations related to sex, age, and region of the country.

Comparatively, our estimate of SCD is higher than the prevalence calculated for the United States24 of 11.1%, and in a Chinese cohort, ranging from 14.4% to 18.8%.25

Other studies performing harmonization of 15 different cohorts found a prevalence of SCD ranging from 5% to 58%,9, 26 which may be explained by the use of different diagnostic criteria and cultural perception of memory complaints.

Some studies also in high-income countries have found higher estimates of cognitive complaints in the elderly, ranging from 50% to 80%.27, 28

We found an estimated prevalence of SCD of 29.21% among Brazilian older adults, with variations related to sex, age, and region of the country.

Comparatively, our estimate of SCD is higher than the prevalence calculated for the United States24 of 11.1%, and in a Chinese cohort, ranging from 14.4% to 18.8%.25

Some studies also in high-income countries have found higher estimates of cognitive complaints in the elderly, ranging from 50% to 80%.

The prevalence of SCD varied across ages, genders, and regions. We demonstrated that women present increased frequency of SCD.

In general, women presented higher rates of SCD than men in both adults and older adults and in all regions.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Alzheimer’s disease is more present in women than men29, 30 and that female sex is also a risk factor for SCD.12

In addition, depression and anxiety are more prevalent in women worldwide31 and in Brazil,32 which could account for a higher rate of SCD.

The strength of the association is higher in women for some risk factors, such as hypertension33 and diabetes,34 which indicates that there are differences between the sexes in the impact of some cardiovascular risk factores on cognitive complaints.35

We also found that older adults (60 years of age or older) presented a higher frequency of SCD than adults (between 50 and 60 years old) in this cohort, which is expected as cognitive complaints increase with age, together with the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.10

The prevalence of SCD varied across ages, genders, and regions. We demonstrated that women present increased frequency of SCD.

The strength of the association is higher in women for some risk factors, such as hypertension33 and diabetes,34 which indicates that there are differences between the sexes in the impact of some cardiovascular risk factores on cognitive complaints.35

We also found that older adults (60 years of age or older) presented a higher frequency of SCD than adults (between 50 and 60 years old) in this cohort, which is expected as cognitive complaints increase with age, together with the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.10

Modifiable risk factors for dementia were also identified as predicting likelihood of SCD.

The evaluation of these risk factors in individuals with SCD may represent a unique opportunity for preventive interventions and with guiding policy-making decisions.7

We observed a particular increased frequency of low educational attainment, hearing loss, and physical inactivity in this study, as related to SCD.

These findings were similar to those found by a Chinese SCD cohort.25 In fact, educational level was inversely related with the prevalence of SCD in our study, which corroborates previous findings.24

Although ideally all individuals should be targeted to control risk factors for dementia, individuals with SCD may be prioritized for aforementioned risk factor control due to an optimal momentum of intervention, that is, patients that looked for medical assistance with cognitive complaints.

We observed a particular increased frequency of low educational attainment, hearing loss, and physical inactivity in this study, as related to SCD.

Our findings suggest that hearing loss was the most robust predictor of SCD in the ELSI-Brazil sample.

The association of hearing loss with SCD has been poorly explored in previous studies, but it was observed in a large US SCD cohort.36, 37

This finding has not yet been described in LMIC populations, where most individuals with hearing loss reside.38

Age-related hearing loss poses a complex interaction with depression and cognitive decline39 and potential mechanisms explaining this link include social deprivation as a result of reduced interaction with others and increased cognitive load to compensate for diminished hearing (such as lip-reading).38

Moreover, male individuals presenting SCD had a higher frequency of hearing loss along with other factors than female individuals, which corroborates previous findings.36, 40

Our findings suggest that hearing loss was the most robust predictor of SCD in the ELSI-Brazil sample.

Early identification and treatment of hearing loss complaints are cornerstones in avoiding complications associated with this condition.

In this context, public health strategies focused on primary care are likely to be more appropriate for the early identification of this condition.

Individuals characterized as SCD presented worse depressive symptoms and feelings of loneliness.

Increased psychological distress symptoms may reflect the mental health status of this population. E4

ven though we excluded individuals with a previous diagnosis of depression, the association of the depressive score with SCD could mean undiagnosed depression.

We also found an association of SCD with feelings of loneliness and poor sleep quality.

Feeling of loneliness41 and self-reported poor sleep quality have been increasingly associated with cognitive decline42 and sleep dysregulation has been repeatedly pointed to as a risk factor for dementia.43

Further studies may clarify whether these factors are predictors of future cognitive decline.

Feeling of loneliness41 and self-reported poor sleep quality have been increasingly associated with cognitive decline42 and sleep dysregulation has been repeatedly pointed to as a risk factor for dementia.43

Along with the established risk factors for dementia, SCD was robustly associated with self-identified race.

It is notable that Brown/Pardo and Black races were associated with increased frequency of SCD in our study.

Not only poor cardiovascular health, but also racial inequalities and social background disparities may favor the increase in risk of SCD among Brown/Pardo and Black individuals, which corroborated previous data associating ethnicity disparities with dementia risk.44

These populations are particularly vulnerable to worse health outcomes,45 such as increased mortality rates during the pandemic in Brazil.46

This analysis may support an action by Brazilian authorities to consider special strategies to better protect populations more vulnerable to incident dementia.

It is notable that Brown/Pardo and Black races were associated with increased frequency of SCD in our study.

There are some limitations in this study.

Due to the high frequency of missing data of some variables we used to define SCD in this sample, many individuals were excluded from the analysis.

However, the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the excluded individuals were similar to those of the analyzed subsample, which suggests that these findings may have national representativeness, and a sensitivity analysis confirmed that missing data were not substantial (Table S6). In addition, data collected must be carefully interpreted.

As information of each participant was self-reported, the possibility of a memory bias cannot be excluded and may have impacted the results.

Because data were self-reported, individuals may over- or underestimate their cognitive complaint according to their mood level at the time of data collection. Another limitation is related to SCD definition.

The exclusion of depression to fulfill SCD criteria is a matter of debate, since depression can cause cognitive complaints and also may indicate an earlier manifestation of Alzheimer’s pathology.47, 48

Nevertheless, the association of depressive symptoms and SCD could help improve the understanding of the causes of cognitive complaints in Brazil.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, SCD is frequent in Brazil, varying according to sex, age, and country region.

Individuals with SCD presented a higher frequency of low education, hearing loss, physical inactivity, and psychological distress when compared with cognitively unimpaired individuals.

Hearing loss complaint was the most robust factor associated with SCD.

Findings presented here can provide valuable insights for public health strategies across the country that may mitigate the negative effects of preventable risk factors for dementia in this population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by an Alzheimer’s Association Grant (AACSFD-22–928689). RMC is funded by the Alzheimer’s Association Grant (AARGD-21–846545).

References and additional information

See the original publication https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

About the authors & affiliations

Wyllians Vendramini Borelli MD, PhD,Eduardo R. Zimmer PhD,Andrei Bieger BSc,Bruna Coelho,Tharick A. Pascoal MD, PhD,Márcia Lorena Fagundes Chaves MD, PhD,Rebecca Amariglio PhD,Raphael Machado Castilhos MD, PhD

1CognitiveandBehavioralNeurologyCenter,NeurologyService,HospitaldeClínicasdePortoAlegre,PortoAlegre,RioGrandedoSul,Brazil

2GraduateResearchPrograminBiologicalSciences:PharmacologyandTherapeutics,FederalUniversityofRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),PortoAlegre,RioGrandedoSul,Brazil

3GraduateResearchPrograminBiologicalSciences:Biochemistry,FederalUniversityofRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),PortoAlegre,RioGrandedoSul,Brazil

4DepartmentofPharmacology,FederalUniversityofRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),PortoAlegre,RioGrandedoSul,Brazil

5FederalUniversityofPelotas,Pelotas,RioGrandedoSul,Brazil

6DepartmentofNeurologyandPsychiatry,UniversityofPittsburghSchoolofMedicine,Pittsburgh,Pennsylvania,USA

7DepartmentsofNeurology,MassachusettsGeneralHospitalandBrighamandWomen’sHospital,HarvardMedicalSchool,Boston,Massachusetts,USA

8GraduatePrograminMedicine,FederalUniversityofRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),PortoAlegre,RioGrandedoSul,