Africa urgently needs to guarantee its own health security

Five steps:

- Invest in health and disease

- Build regional control and capability

- Accelerate translational research and development

- Invest in early-warning systems

- Build centralized governance.

Nature, Comment

Christian T. Happi & John N. Nkengasong

03 January 2022

Researchers receive diagnostics training at the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID) in Ede, Nigeria.Credit: ACEGID

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Africa’s rapid and coordinated response, informed by emerging data, was remarkable. Now, in 2022, as vast vaccination campaigns have enabled the global north to gain some control over the pandemic, Africa lags behind.

Since the 1960s, when many African countries gained independence, the continent has largely depended on the outside world for its health-security commodities: diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines, as well as personal protective equipment and other medical supplies. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed how easily international cooperation and multilateral agreements can dissolve, especially in the face of a global crisis — and just how vulnerable this dependence leaves Africa. In 2017 and 2018, more than 120 disease outbreaks were reported on the continent.

In our view, leaders of the 55 African Union member states face a stark choice.

In principle, Africa could build on the astonishing gains it has made in surveillance and public-health responsiveness to outbreaks in recent years.

It could sufficiently invest in commodities to ensure its health security, and position itself as a world leader in fighting infectious diseases.

The alternative? There really isn’t one.

If the continent does not work towards guaranteeing self-sufficiency, it will fail to address the infectious-disease threats of the twenty-first century. It will thereby be unable to achieve the development goals encapsulated in the African Union’s Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. This is a blueprint for transforming the continent into a global powerhouse, laid out in 2013.

What Africa got right

In 2017, following the 2014–16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the African Union launched the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) to help prepare the continent for epidemics and pandemics.

Millions of dollars of investment by members of the African Union and organizations such as the Africa Development Bank, the World Bank, partner nations and foundations have bolstered the capability of the Africa CDC and its Regional Collaborating Centres to handle disease outbreaks. The regional centres are networks of public-health institutions hosted in Egypt, Kenya, Zambia, Gabon and Nigeria for the northern, eastern, southern, central and western regions, respectively.

Just days after the first case of COVID-19 was reported in Egypt in mid-February 2020, the African Union and the Africa CDC convened an emergency meeting of all ministers of health in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Attendees agreed to a Joint Continental Strategy, whereby African Union member states would cooperate, collaborate, coordinate and communicate their efforts. The Africa CDC had already established the Africa Task Force for Coronavirus (AFTCOR) in early February 2020 to help achieve this.

In early March 2020, as cases of COVID-19 spread across the continent, countries took immediate and drastic measures, including implementing lockdowns and other restrictions designed to reduce transmission. This continent-wide collaboration was sustained. Since March 2020, AFTCOR has conducted bi-weekly meetings. The Bureau of the Assembly of the African Union Heads of State and Government (a body that coordinates the affairs of the African Union between the union’s yearly summits) has also convened nearly every month to review Africa’s response to the pandemic, with the Africa CDC providing technical guidance.

So far, 12 initiatives have been launched because of this coordination.

These include the Partnership to Accelerate COVID-19 Testing in Africa, which has helped to secure diagnostics; the Africa Medical Supplies Platform, which has enabled the purchasing of crucial medical supplies; and the African Vaccine Acquisition Task Team (AVATT), a centralized purchasing agent established in November 2020 to make it easier for African Union member states to secure vaccines. So far, AVATT has enabled the continent to obtain 400 million doses of vaccines.

Meanwhile, Africa’s centres for genomics have achieved impressive feats in surveillance.

Coordination has come from the Africa CDC and national public-health institutions, such as the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control in Abuja. In March 2020, the first African SARS-CoV-2 genome was sequenced in Nigeria, only 48 hours after a sample (from a patient who had travelled from Italy) arrived at the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID) in Ede, with results released after 72 hours (see go.nature.com/3ywdobt).

In October that year, the Beta variant was discovered within days of a sample reaching the Network for Genomic Surveillance South Africa consortium, a collaboration of laboratories, researchers and academic institutions across the country. In November 2021, the heavily mutated Omicron variant was spotted in genome-sequencing data from Botswana and identified by researchers in South Africa.

Indeed, the best-resourced genomic centres have supported many other countries besides their own.

So far, ACEGID (which C.T.H. directs), for instance, has sequenced samples from around 30 African countries. Researchers working at the centre have also trained more than 1,300 geneticists and public-health workers and officials from other countries in diagnostics and genomics for infectious diseases. After three weeks, trainees return to their own countries and apply what they have learnt, even though their equipment might be more basic than ACEGID’s.

All of these sequencing efforts continue to guide local, regional, national and international public-health responses.

Between April and July 2020, for instance, sequencing information obtained in Nigeria revealed that people were obeying lockdown restrictions during the day, but did so less at night. Most recently, alerting the world to the Omicron variant has spurred intensified surveillance in Africa and an explosion of new immunology and sequencing research, as well as changes to public policy in the global north.

Such feats in coordination and collaboration — which have enabled many African nations to make the best use of available resources — stand in contrast to the inflexibility seen in other parts of the world.

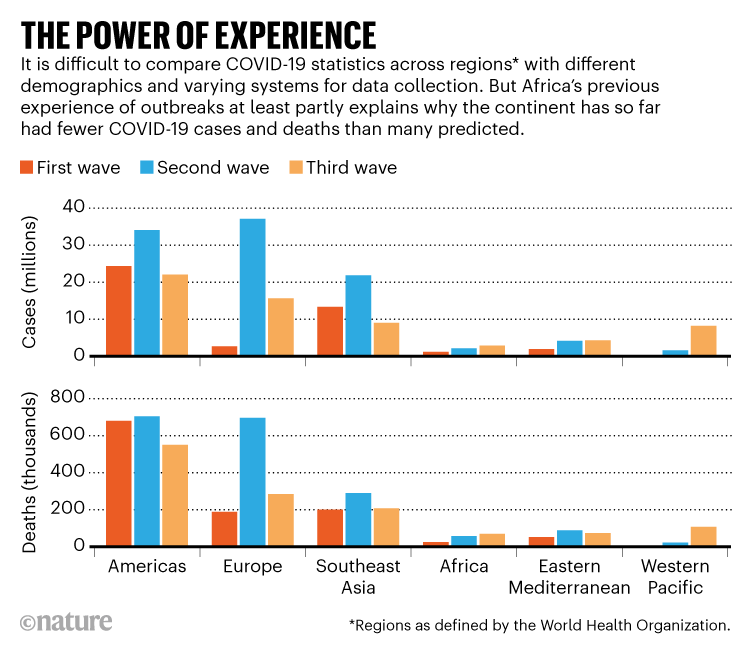

Indeed, Africa’s achievements, especially in the early phase of the pandemic, are at least part of the reason the continent was able to mitigate the first and, to some degree, the second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic (see ‘The power of experience’).

As of 13 December 2021, around 8.9 million cases of COVID-19 and nearly 225,000 deaths had been reported across Africa ( https://africacdc.org/covid-19).

This is in contrast to early models from public-health experts and epidemiologists, which had predicted that up to 70 million Africans would be infected with SARS-CoV-2 by June 2020, with more than 3 million people dying.

What’s happened since?

In the early months of the pandemic, more than 70 countries imposed restrictions on the export of medical materials — including the raw materials needed to make diagnostics.

It wasn’t until the African Union established the Africa Medical Supplies Platform in June 2020 that the continent was able to start procuring medical supplies at a pace that better met demand.

Now, leaders of African countries are desperately trying to access COVID-19 vaccines.

Around 47% of people have been fully vaccinated globally, and many countries in the world are giving a further (booster) dose to their citizens. Yet Africa is still struggling — it has achieved full coverage in only about 7% of eligible people (currently, those who are 18 or older).

This is despite the promises of donors to make two billion vaccine doses available to people living in low- and middle-income countries by the end of 2021 through COVAX — an initiative launched in April 2020 by the World Health Organization, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and CEPI, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations.

The inequity of the COVID-19 pandemic is reminiscent of the moral catastrophe that occurred during the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the mid-1990s, as one of us (J.N.N.) warned in these pages more than a year ago.

Before the establishment of programmes such as the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, more than ten million Africans died needlessly because they couldn’t obtain the antiretroviral drugs that were readily available in wealthy nations.

What has happened during the COVID-19 pandemic should be a stark reminder to African leaders of the fragility of international cooperation and multilateralism. But the lessons it holds for Africa go deeper even than this.

What has happened during the COVID-19 pandemic should be a stark reminder to African leaders of the fragility of international cooperation and multilateralism. But the lessons it holds for Africa go deeper even than this.

The downsides of aid

Historically, efforts to assist Africa have tended to be siloed.

They take a top-down approach, with decision-making coming from a central body outside the continent, not from African institutions and experts. Efforts have generally focused on short-term crisis management, not on the kinds of sustainable systems, such as manufacturing capability for diagnostics, that could help Africa to take charge of its health security.

Take the 2014–16 Ebola epidemic. The outbreak wasn’t formally classified as a global health emergency until nearly 2,000 cases and nearly 1,000 deaths had already been reported in West Africa. Many more lives might have been saved had there been institutions in Africa, working directly with first responders on the ground, that were empowered to alert the world. When international aid did arrive from numerous countries, the many organizations involved — with their different messaging and ways of working — heightened people’s confusion about the source of the virus and how best to combat it.

Ultimately, Africa’s dependence on the outside world sustains a lack of confidence in Africa — both within and outside the continent.

Certainly, Africa’s successes in the COVID-19 pandemic have not been reported in the mainstream media in a way that could enable the world to learn from them. Instead, the conversation has focused mainly on whether problems with data collection, demographics, climate or other factors could explain why far fewer cases and deaths have been reported than epidemiologists and others predicted,.

Five steps

- Invest in health and disease

- Build regional control and capability

- Accelerate translational research and development

- Invest in early-warning systems

- Build centralized governance

Multilateralism will always be crucial to preventing and responding to epidemics and pandemics.

But Africa will be able to benefit from the advances it has made in disease surveillance only if its approach to public health is reconfigured towards self-reliance.

This could be achieved in five steps.

1.Invest in health and disease.

African leaders must honour their commitments to allocate at least 15% of their annual budgets to the health sector, as they agreed to do in 2001 at a meeting on HIV and other diseases in Abuja. Today, spending on health across the continent ranges from 0.1% to 2% of a nation’s gross domestic product.

Renewing this commitment is especially urgent as the goals articulated in the Agenda 2063 begin to be realized. For instance, the African Continental Free Trade Area agreement, which came into force in January this year, creates a trade area including 1.3 billion people across 55 countries. Likewise, the African Union’s Protocol on Free Movement of Persons in Africa will enable people to move around the continent without a visa. Both of these steps are crucial to economic development. They also come with major public-health implications.

2.Build regional control and capability.

This means strengthening national public-health institutions, such as the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and the Zambia National Public Health Institute in Lusaka.

It also means strengthening and empowering the Africa CDC and its five Regional Collaborating Centres. These are the ‘Africa-owned institutions’ that are crucial to prevent, detect and respond to public-health threats.

Ultimately, both national public-health institutions and regional centres must be the command centres for the control of disease outbreaks.

3.Accelerate translational research and development.

Currently, Africa imports 70–90% of its drugs; there is almost no biotechnology sector.

For comparison, China and India, with comparable populations, import 5% and 20%, respectively.

There is also a severe shortage of human resources.

There are currently only around 1,900 epidemiologists in Africa — far fewer than the 6,000 needed, as stipulated by the Global Health Security Agenda. (The Global Health Security Agenda is an international effort to accelerate the implementation of health regulations, particularly in developing countries, to improve capacity in preventing and responding to infectious-disease threats.)

Governments, philanthropists and the private sector, such as the African Export-Import Bank and Africa Development Bank, must provide sustainable funding for research and development, with a focus on

- diagnostics,

- therapeutics and

- vaccines for infectious and non-communicable diseases.

Such investment will be crucial to lure back the thousands of African scientists, clinicians, nurses and other skilled medical health workers who have gone overseas for training or employment.

Accelerating translational research and development will also require continued investment in the existing genomics hubs of academic excellence in Africa.

4.Invest in early-warning systems.

Ultimately, Africa — and the world — needs effective surveillance to detect and characterize deadly pathogens before they spread across the globe.

Some promising initiatives are being developed in Africa, such as SENTINEL (see ‘A sentinel for disease’), which one of us (C.T.H.) is leading.

To be effective in the long term, such schemes must be integrated into Africa’s public-health institutions.

Too many projects on health and disease in Africa are pursued in silos and funded only for as long as the principal investigator spearheading the project can persuade investors.

The Regional Integrated Surveillance and Laboratory Network (RISLNET) was launched by the Africa CDC in 2017 to enable the rapid detection and prevention of emerging public-health threats.

Surveillance networks consisting of genomics laboratories and National Public Health Laboratories have already been established in Central Africa, and efforts are ongoing to expand these in southern, eastern and western Africa.

In principle, systems such as SENTINEL could be incorporated into RISLNET to ensure that they are in line with what the African Union members envision for the continent, and that they have institutionalized and politicized backing.

Such systems must integrate the surveillance of disease in people, animals and the environment.

Since February 2020, those involved in the One Health programme at the Africa CDC have been trying to foster this holistic approach — mainly by bringing together people working in these different areas.

5.Build centralized governance.

An African Pandemic Preparedness and Response Authority, as proposed by the African Union in October 2021, could empower the Africa CDC to coordinate pandemic responses across borders.

This agency could be modelled on the European Health Emergency preparedness and Response Authority (HERA).

A signed treaty would mean leaders have to cooperate, share data and so on.

Likewise, the continent could capitalize on practices and tools born out of the COVID-19 crisis.

The African Union COVID-19 Response Fund, established in March 2020, has enabled countries to pool funds to buy medical commodities, such as personal protective equipment. In principle, this could be upgraded to an African Disease Threat Fund.

Similarly, AVATT could be used as a platform for acquiring other vaccines for the continent.

The way ahead

Unlike in previous disease outbreaks, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Africa has been a key player in the acquisition of scientific knowledge that has guided the global response.

For two years, hundreds of geneticists across the continent have worked seven days a week, often through the night, to sequence strains of SARS-CoV-2. And companies worldwide have used these data (most of which are available in public repositories such as GISAID) to develop COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics. For those contributing so much to the global effort to curb this pandemic, it is galling to watch Africa continue to struggle in the acquisition and roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines.

The new way of doing public health that we set out here offers a different future.

Embracing it is an imperative for Africa’s security and economic survival. It will also benefit the world — as so powerfully demonstrated in November 2021 by the discovery of the Omicron variant.

BOX: A sentinel for disease

An early-warning system being developed in Africa could transform people’s ability to prevent and respond to disease outbreaks throughout the world.

One of us (C.T.H.) has been working on the SENTINEL initiative6, in collaboration with geneticist Pardis Sabeti at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, since January 2020. The project has three goals.

Detection. The idea is to use a series of three new diagnostic techniques to detect diseases. The first uses CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing to detect known viruses in a simple, inexpensive test for the highest-priority pathogens in a region. This can be used wherever a patient is receiving care — even in their own home. If this test fails to identify a pathogen, a blood sample taken at a primary-care facility and sent to a local hospital would be subject to a more expensive test. This detects hundreds of viruses and viral strains simultaneously. If this also fails to detect a known pathogen, a sample would then be sent to a regional sequencing centre for metagenomic sequencing. There, every virus — known and unknown — can be identified and tracked by sequencing all the DNA in the sample.

So far, researchers at ACEGID and the Broad have validated three CRISPR-based diagnostics — for Ebola, Lassa fever virus and SARS-CoV-2 (ref. 7). These technologies have also been incorporated into a single test that can detect up to 169 viruses simultaneously in a single sample7,8.

Connection. Alongside better tools for the detection and surveillance of disease, researchers at the Broad and at ACEGID are building tools to enable the integration of all sorts of data sources — from diagnostic and clinical data obtained by health-care workers, to genomic surveillance data gathered across a continent. The aim is to make all these data streams available (and connected in real time) on a continent- or region-specific cloud-based dashboard. Given the limited resources in Africa, and in many of the other regions where SENTINEL could operate, many of these tools are being designed specifically for scientists, laboratory staff and public-health workers who might have limited computational experience or on-site hardware resources.

Empowerment. Diagnostic and informatics technologies are futile unless they are used to guide clinical care and public-health interventions. To be effective, SENTINEL must empower every stakeholder, whether governments and public-health officials, front-line health-care workers, scientists or communities and individual patients.

Training people in genomic sequencing, diagnostics, bioinformatics and advanced genomic surveillance (metagenomics sequencing) will be crucial for SENTINEL to be effective in the long term. So far, researchers at the Broad and at ACEGID have trained more than 1,300 local health-care workers and scientists to use SENTINEL’s diagnostic and surveillance tools. Ultimately, tens of thousands will need to be trained.

Originally published at https://www.nature.com.

Christian T. Happi

- Christian T. Happi is director at the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID) and professor of molecular biology and genomics, Redeemer’s University, Ede, Nigeria; and visiting professor in the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

John N. Nkengasong

- John N. Nkengasong is director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, African Union, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.