The Health Transformation . Institute

research institute and knowledge portal

Joaquim Cardoso MSc*

Chief Researcher, Editor and Strategy Officer (CSO)

November 17, 2022

*MSc from London Business School — MIT Sloan Masters Program

Source: Financial Times

What are the key points?

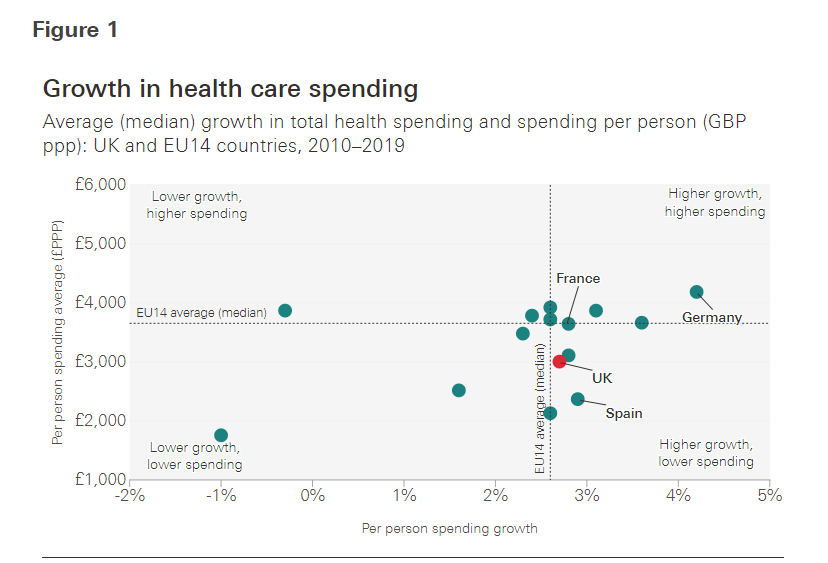

- This analysis examines how health care spending in the UK compares with EU countries in the decade preceding the pandemic. Taking a longer term view enables us to see how trends in spending may have impacted health care resilience today.

- Average day-to-day health spending in the UK between 2010 and 2019 was £3,005 per person — 18% below the EU14 average of £3,655.

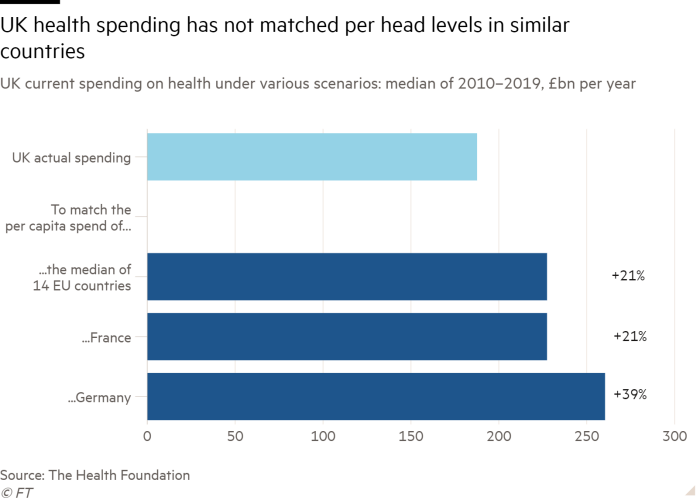

- If UK spending per person had matched the EU14 average, then the UK would have spent an average of £227bn a year on health between 2010 and 2019 — £40bn higher than actual average annual spending during this period (£187bn).

- Matching spending per head to France or Germany would have led to an additional £40bn and £73bn (21% to 39% increase respectively) of total health spending each year in the UK.

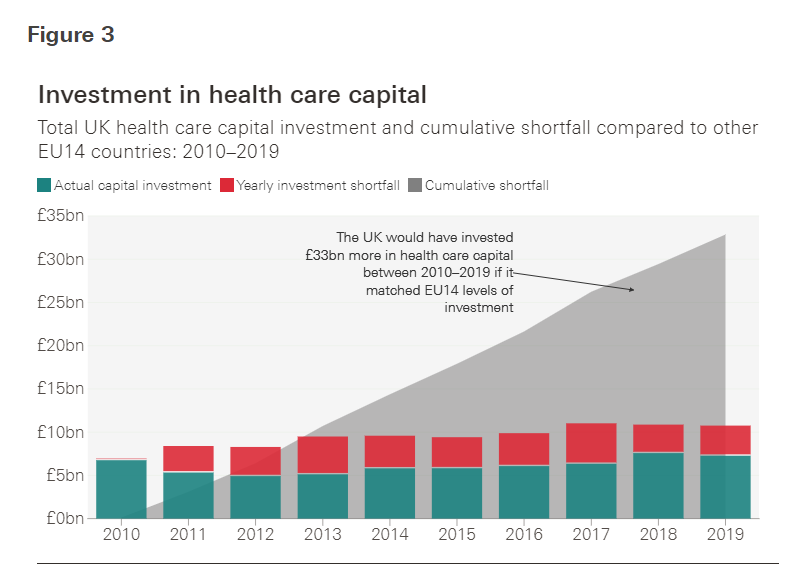

- Over the past decade, the UK had a lower level of capital investment in health care compared with the EU14 countries for which data are available.

- Between 2010 and 2019, average health capital investment in the UK was £5.8bn a year. If the UK had matched other EU14 countries’ average investment in health capital (as a share of GDP), …

- the UK would have invested £33bn more between 2010 and 2019 (around 55% higher than actual investment during that period).

Infographic

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

UK health spending over past decade lags Europe by £40bn a year

Financial Times

November 16, 2022

The UK has spent around 20 per cent less per person on health each year than similar European countries over the past decade, according to new research that shows how the NHS has been consistently starved of funding.

The data from the Health Foundation, which was shared with the Financial Times, found that health spending in the UK would have needed to rise by an average of £40bn per year in the past decade to match per capita health spending across 14 EU countries.

It comes as the government prepares to reveal its spending plans in Thursday’s Autumn Statement and casts fresh light on how a decade of austerity has affected the NHS, which is foundering as it braces for its hardest ever winter.

Last month the NHS’s finance chief warned the service was facing a £ 7bn black hole next year, in part due to the impact of inflation, which is eating into hard-won funding settlements.

Steve Barclay, health and social care secretary, hinted in a speech to the NHS Providers annual conference on Wednesday that the health service would receive more money in the Statement to help it cope with rising prices. “I can absolutely confirm we do need support to meet those inflationary pressures.”

Last month the NHS’s finance chief warned the service was facing a £ 7bn black hole next year, in part due to the impact of inflation, which is eating into hard-won funding settlements.

Meanwhile, the lag between the UK and similar countries in expenditure levels revealed in the Health Foundation data, is matched by a gulf in survival rates for some conditions.

In the UK, just 13 per cent of those diagnosed with lung cancer live for at least five years, according to 2014 data, the most recent available.

This is the lowest among the countries studied, with Japan at the top on 33 per cent.

In the UK, just 13 per cent of those diagnosed with lung cancer live for at least five years, according to 2014 data, the most recent available. This is the lowest among the countries studied, with Japan at the top on 33 per cent.

Meanwhile, 9 per cent of people in the UK who had the most common type of stroke died within 30 days in 2019, compared with 6.2 per cent in Germany.

Meanwhile, 9 per cent of people in the UK who had the most common type of stroke died within 30 days in 2019, compared with 6.2 per cent in Germany.

“Either we are going to have lower quality healthcare relative to other countries or we spend more,” said Anita Charlesworth, director of research for the Foundation, who led the work.

In the decade before the pandemic the UK spent on average around a fifth less on day-to-day health costs than the major EU countries studied.

During the Covid crisis, spending increased by 14 per cent compared to the EU14 average of just below 6 per cent.

However this high level of spending had been needed to compensate for years of attrition in the run-up to the crisis, Charlesworth said.

The UK’s total healthcare budget was £187bn per year, on average, between 2010 and 2019. It would have needed to have spent £227bn to match the average across the EU14 over the pre-pandemic decade.

The UK’s total healthcare budget was £187bn per year, on average, between 2010 and 2019. It would have needed to have spent £227bn to match the average across the EU14 over the pre-pandemic decade.

The increased funding meant that other countries were able to benefit from years of greater investment when the pandemic struck.

In Germany, for example, a larger number of beds and higher staffing ratios than in the NHS helped to ensure the crisis did not disrupt other healthcare.

Professor Heyo Kroemer, chief executive of the Charite hospital in Berlin, one of Europe’s biggest academic medical centres, said that although some elective work was postponed and other activity reduced, there was no wholesale halt to non-Covid treatment and large waiting lists had not built up in the way they had in the UK.

He added that even though significant numbers of staff were currently ill with Covid the wait for a hip replacement, for example, was no more than a couple of weeks: “That is still in a time which you can stand,” he pointed out. In contrast, the median waiting time for patients waiting to start such elective treatment in England at the end of September was 14 weeks.

The Health Foundation research shows that the UK would have had to spend an additional £73bn, or 39 per cent more, in every year between 2010 and 2019 to match Germany.

The Health Foundation research shows that the UK would have had to spend an additional £73bn, or 39 per cent more, in every year between 2010 and 2019 to match Germany.

Just four of the countries studied — Spain, Portugal, Italy and Greece — spent less per person than the UK over the same period.

However, Charlesworth pointed out that this shortfall mainly resulted from a lack of spending on social care, reflecting a southern European tradition of families caring for loved ones.

However, … this shortfall mainly resulted from a lack of spending on social care, reflecting a southern European tradition of families caring for loved ones.

The researchers also looked at Britain’s capital health spending on buildings, technology and equipment compared to its European neighbours.

Although the available data only allowed comparisons to be made for eight countries, it found that between 2010 and 2019, an additional £33bn in cumulative UK investment in capital health infrastructure would have been needed to match the total EU average invested over the period.

This would have required investment to be 55 per cent higher than it actually was.

… between 2010 and 2019, an additional £33bn in cumulative UK investment in capital health infrastructure would have been needed to match the total EU average invested over the period.

This would have required investment to be 55 per cent higher than it actually was.

The picture is not entirely bleak.

Extolling the NHS’s screening services and the low sums it spent on administration, Charlesworth said: “There are real structural strengths to our system which enable us to use the precious resources more efficiently than many other countries and try to extract good health outcomes for that spend.”

“There are real structural strengths to our system which enable us to use the precious resources more efficiently than many other countries and try to extract good health outcomes for that spend.”

However, she added that there was “only so far efficiency can take you”.

The Department for Health and Social Care said the NHS budget had been increased from £123.7bn in 2019–20 to more than £162bn in 2024–25.

The Department for Health and Social Care said the NHS budget had been increased from £123.7bn in 2019–20 to more than £162bn in 2024–25.

It added that it planned to spend more than £8bn over three years to support elective recovery, and £5.9bn on NHS capital “to provide new beds, equipment and technology”.

It added that it planned to spend more than £8bn over three years to support elective recovery, and £5.9bn on NHS capital “to provide new beds, equipment and technology”.

Originally published at https://www.ft.com on November 16, 2022.

APPENDIX: Excerpt

How does UK health spending compare across Europe over the past decade?

The Health Foundation

Icaro Rebolledo, Anita Charlesworth

16 November 2022

Why is the UK spending and investing less?

Some of the differences in spending may be a result of different demographic characteristics (for instance, 5% of the UK population is aged 80 years and older, compared with 6% in France and close to 7% in Germany).

Differences may also potentially arise from more efficient use of resources in the UK (administration costs in the UK are lower than the EU14 average, accounting for 1.9% of total current expenditure, compared with a 3% EU14 average as of 2020).

But the magnitudes of the yearly differences in spending and investment between the UK and these other countries may point towards sustained suboptimal spending per head on health care in the UK.

The knock-on impact of this underinvestment could affect access (longer waiting lists), quality (overstretched staff or lack of investment in technology), in turn leading to a less resilient system.

Even before the pandemic, the proportion of people in the UK self-reporting that they needed treatment but could not access it was one of the highest in Europe.

So, systems that are already running at capacity may become reliant on emergency funding or on having to redeploy resources and deprioritise certain services to deal with surges in demand.

Where does underspending and underinvestment leave the UK?

The key issue for health spending is what amount of actual resource (health care workers, medicines, diagnostics and beds) it buys.

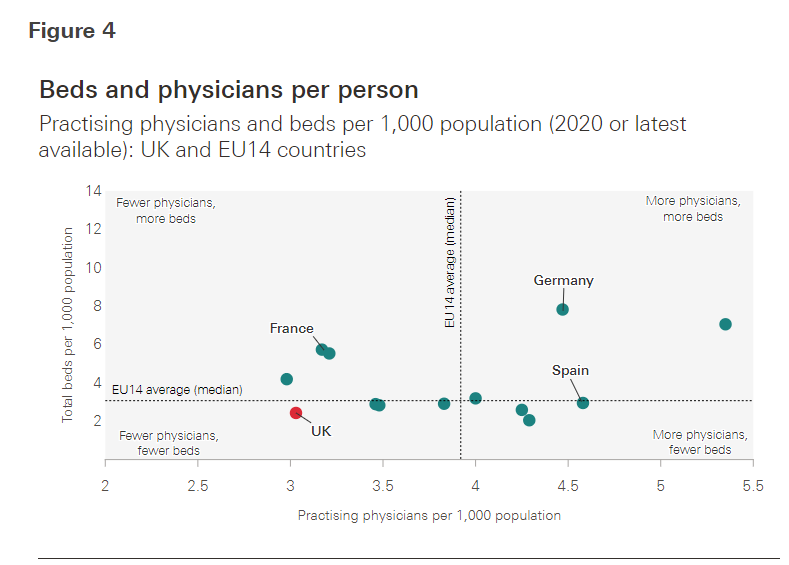

Figure 4 shows that the UK is also an outlier in terms of beds and doctors per head.

- The UK has fewer practising physicians per person and fewer hospital beds per person than the EU14 average.

- The Netherlands has similar beds than the UK but combines this with more staff, using a model where more care is provided in community-based settings.

- The UK therefore stands as an outlier in having both fewer beds and fewer doctors than average.

The UK therefore stands as an outlier in having both fewer beds and fewer doctors than average.

The skills mix could explain some of the differences in doctors per head, but the UK also has fewer nurses than average per head of population (8.7 nurses for every 1,000 inhabitants in the UK compared with 9.9 average nurses for every 1,000 inhabitants in the EU14).

the UK also has fewer nurses than average per head of population (8.7 nurses for every 1,000 inhabitants in the UK compared with 9.9 average nurses for every 1,000 inhabitants in the EU14).

- The UK has a similar number of pharmacists (0.85 for every 1,000 inhabitants in the UK compared with 0.88 average for every 1,000 inhabitants in the EU14)

- and similar total workforce (60.7 for every 1,000 inhabitants in the UK compared with 60.4 average for every 1,000 inhabitants in the EU14), because of different models of health care.

The UK has a similar number of pharmacists (0.85 for every 1,000 inhabitants in the UK compared with 0.88 average for every 1,000 inhabitants in the EU14)

and similar total workforce (60.7 for every 1,000 inhabitants in the UK compared with 60.4 average for every 1,000 inhabitants in the EU14), because of different models of health care.

What can we learn from this comparison?

This analysis shows that over the past decade the UK has spent less on both day-to-day care and investment spending on health care compared with the average EU14 countries.

This is mirrored by less capacity, fewer physical resources and therefore greater vulnerability to sudden surges in demand.

This meant the UK had to increase spending more rapidly than other countries to respond to the pandemic.

This meant the UK had to increase spending more rapidly than other countries to respond to the pandemic.

Of course, international comparisons also have limitations.

Population characteristics differ, and some countries may use resources more efficiently than others and there may be differences in how countries recorded COVID-19 spend.

Overall if the UK had matched EU14 levels of spending per person on health, day-to-day running costs would have been £39bn higher each year, on average, over the past decade (£30.5bn of which would have been additional government spending).

For capital spending, matching the cumulative EU14 average over the past decade would have resulted in the UK investing £33bn more in health-related buildings and equipment.

These are significant gaps in spending. Had UK spending kept up with European neighbours it is fair to assume the NHS would have been more resilient and had greater capacity to provide care during the pandemic and reduce the large backlog of care that is its legacy.

Originally published at https://www.health.org.uk

Names mentioned

Steve Barclay, health and social care secretary,

Professor Heyo Kroemer, chief executive of the Charite hospital in Berlin,