institute for

continuous health transformation (CHT)

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Chief Editor, Researcher

and Senior Advisor

January 12, 2023

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

British scientists have launched a new initiative, the Respiratory Virus and Microbiome Initiative, to expand the sequencing of common seasonal respiratory viruses …

… with the aim of developing an early warning system for new viral threats and help prevent future pandemics.

- The project, run in collaboration with the UK Health Security Agency and other scientists, will track and sequence the evolution of respiratory virus pathogens like SARS-Cov-2, …

- … as well as other coronaviruses, flu families, and respiratory syncytial viruses (RSV) in order to establish a “large-scale genomic surveillance system for respiratory viruses.”

- The program hopes to “supercharge” research efforts to fill the gap in scientific understanding of the transmission dynamics of respiratory bugs, and improve scientific understanding of the particular characteristics of individual strains that make up respiratory virus families.

- If the program succeeds, it could provide a blueprint for other countries to implement as part of their pandemic preparedness strategies.

If the program succeeds, it could provide a blueprint for other countries to implement as part of their pandemic preparedness strategies.

DEEP DIVE

UK Scientists Launch Genomic Surveillance System For Respiratory Viruses

Health Policy Watch

Stefan Anderson

12/01/2023

British scientists have launched a new initiative to expand the sequencing of common seasonal respiratory viruses with the aim of developing an early warning system for new viral threats and help prevent future pandemics.

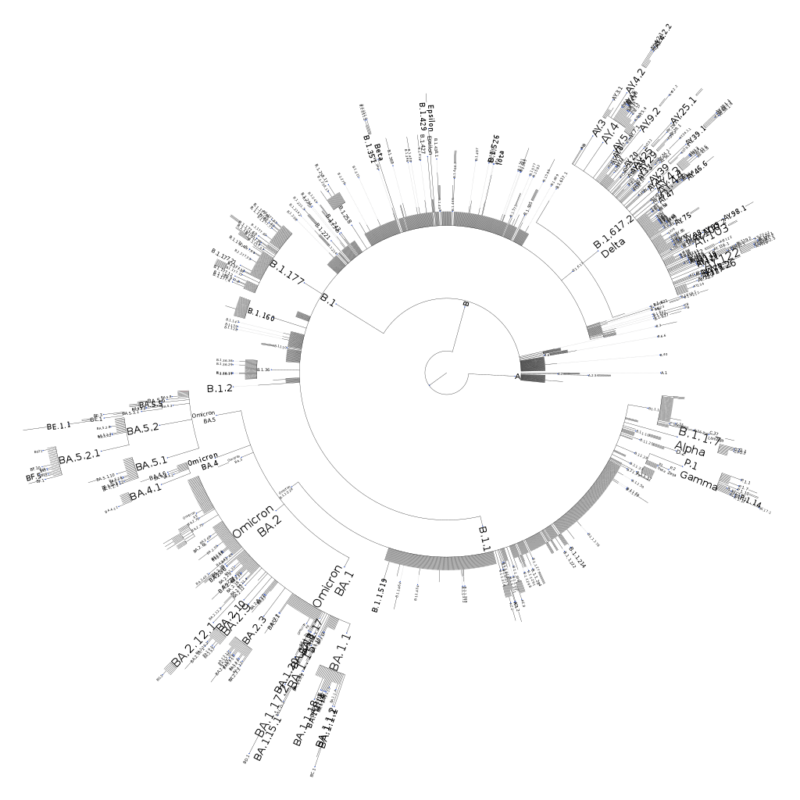

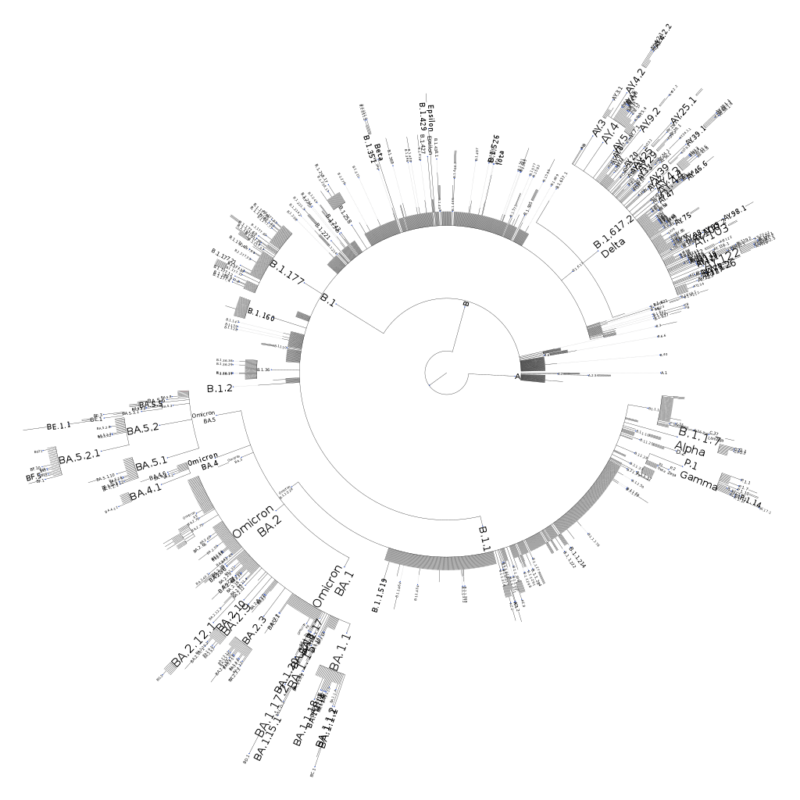

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, labs around the world were sequencing tens of thousands of Sars-CoV-2 genomes a day.

The data being shared from around the world allowed health authorities to keep pace with the evolution of the virus responsible for causing COVID-19, and identify where the next threat was coming from.

The Respiratory Virus and Microbiome Initiative launched on Tuesday by researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute aims to build on these lessons.

The project, run in collaboration with the UK Health Security Agency and other scientists, will track and sequence the evolution of respiratory virus pathogens like SARS-Cov-2, as well as other coronaviruses, flu families, and respiratory syncytial viruses (RSV) in order to establish a what it calls a “large-scale genomic surveillance system for respiratory viruses.”

“It comes out of the simple idea that what we’ve done for Covid, we should now be doing for all respiratory viruses because if we can establish a better understanding of these viruses, we can be in a better place to understand their transmission and how to develop vaccines against them,” Dr Ewan Harrison, who is leading the initiative, the Guardian.

“It comes out of the simple idea that what we’ve done for Covid, we should now be doing for all respiratory viruses because

Viral genome sequencing expanded significantly during the pandemic.

The public release of the Sars-CoV-2 sequence by Chinese scientists in January 2020 allowed the world to start developing diagnostics and vaccines within days, saving millions of lives.

To date, scientists have shared millions of Sars-CoV-2 sequences on public databases.

Influenza has attracted a lot of research interest over the years.

However, many other respiratory bugs, like rhinovirus or adenovirus, are poorly monitored, leading to a gap in scientific understanding of their transmission dynamics.

By providing large amounts of data for academics and public health officials to use in their work, the program hopes to “supercharge” research efforts to fill these blind spots and improve scientific understanding of the particular characteristics of individual strains that make up respiratory virus families.

By providing large amounts of data for academics and public health officials to use in their work, the program hopes to “supercharge” research efforts to fill these blind spots and improve scientific understanding of the particular characteristics of individual strains that make up respiratory virus families.

“Understanding which specific strains of each virus is causing disease in patients, and if there are multiple strains or multiple viruses present at any one time will hugely change our understanding of how viruses lead to disease, which viruses tend to coexist, and the severity of disease caused by each virus,” Dr Catherine Hyams, an expert in respiratory viruses at the University of Bristol.

If the program succeeds, it could provide a blueprint for other countries to implement as part of their pandemic preparedness strategies — and become a cornerstone of global defenses against viral threats in the future.

Image Credits: MinMaj.

Originally published at https://healthpolicy-watch.news on January 12, 2023.

People mentioned

Sanger Institute

Dr Ewan Harrison

Dr Catherine Hyams

Dr Antonia Ho

RELATED ARTICLE (The Guardian)

Existing UK surveillance programmes keep track of certain viruses, such as influenza and Covid, by testing a representative sample of patients with respiratory infections using virus-specific PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests. But PCR tests work by probing for known sequences of DNA from specific viruses. If you are not looking for that virus – or it’s DNA sequence has changed – it will not be detected.

Patients may also be tested for specific viruses if their symptoms are severe enough to warrant hospital treatment, to help guide their care. However, there is currently no single test that can detect all respiratory viruses, and patients can have more than one infection at one time, meaning other infections may be missed.

So-called “metagenomic sequencing” gets around this problem by reading out the sequences of all of the genes that are present in a sample, with no assumptions about what to expect. These sequences are then compared to genetic databases to identify which organisms are present.

“It allows you to detect known viruses, but also perhaps new viruses, or viruses that have mutated and are therefore no longer picked up by [standard PCR tests],” said Dr Antonia Ho, a consultant in infectious diseases and clinical senior lecturer at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research.

…

Monitoring for new strains that could escape current treatments or vaccines should also enable scientists to develop new strategies to contain their spread, including better tests, treatments and modified vaccines.