e.g.Black men are disproportionately diagnosed with, and die from, prostate cancer …

Eliminating disparities in routine examinations will require outreach, availability and cultural consideration

Scientific American

By Melba Newsome

December 1, 2021

Executive Summary

by Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Health Revolution Institute

Cancer Revolution Unit

April 20, 2022

What is the problem?

- Men with a PSA level between 4 and 10 have about a one-in-four chance of having prostate cancer. That risk goes to one in two if the level is above 10.

- Black men like Ford are disproportionately diagnosed with, and die from, prostate cancer …

- His experience illustrates two things: cancer screening can save lives, and cancer screening is not accessible for everyone who needs it.

What are the causes?

- Cost and lack of access, health illiteracy, implicit bias, and both cultural and structural barriers all play a role,

- as do disparities in cancer risk and vast differences in how screenings are integrated into patient care.

What are the consequences?

- The result is that too many cancers are detected too late, leading to too many avoidable deaths.

- “The screening for breast, colon, prostate and lung cancer is way below what it should be in the African-American and Latino populations.

One size does not fit all

Medical societies and expert panels constantly reassess their screening guidelines in response to new research, using updated models and the most recent data. The result, however, may be confusing and seemingly inconsistent guidelines

- It can mean huge variations in how these screenings are implemented — among both individual physicians and large health systems — as well as in how insurance companies reimburse for them.

- It can also mean huge variations in which patients receive the screenings they need.

What are the causes?

- This does not acknowledge that Black women tend to have a more aggressive type of breast cancer that strikes at younger ages,…For this group, those researchers recommend starting annual screening at age 40.

- Perhaps even more concerning, researchers such as Schaeffer say, is that medical groups often have homogeneous guidelines that do not account for variations among racial groups

Similar disparities exist in cervical cancer.

- The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 32 percent higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnic group.

- Limiting screening options could undermine cancer-prevention programs in vulnerable populations.

- That is troubling for some clinicians, who attribute disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality to lower access to screening.

Screening guidelines strongly influence who gets referred for screening and what tests insurance providers will cover for whom.

- The trouble is that those guidelines are based on clinical trials conducted with subjects who are predominantly white.

- Research shows that Black people are at a higher risk of lung cancer even if they smoke less over time, and their inclusion in clinical trials could have a significant impact on any screening guidelines that result

Gaps in clinical trials

- In the 2011 National Lung Cancer Screening trial,…fewer than 5 percent of their participants were Black.

- In The European trial on the same topic, the NELSON lung cancer study,…the researchers made no mention of people of African ancestry.

- Clinical trials investigating the benefits of prostate cancer screening also excluded Black men, despite greater incidence and mortality in this population.

Closing the gap

- But some researchers are finally beginning to acknowledge the importance of diversity both in clinical trial participation and in establishing more relevant screening guidelines.

- The USPSTF cited the study earlier this year as a factor in lowering its recommended screening age for lung cancer, from age 55 to 50, and reducing the number of pack years (years of smoking multiplied by the number of packs smoked per day) from 30 to 20, greatly expanding potential access.

- Nevertheless, only 5.7 percent of those at high risk are actually screened, in part because of the dearth of screening centers and lack of awareness.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

La Shawn Ford has always been meticulous about his health. He ate well, exercised regularly and never smoked. But last year, when the 48-year-old Illinois state representative learned that actor Chadwick Boseman had died of colon cancer, he decided to take his health-care game up a notch. In October 2020 Ford scheduled an appointment with his primary care physician for a colonoscopy and, while he was at it, a prostate cancer screening, too.

The colonoscopy came back clean, but his doctor refused to order the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, saying Ford wasn’t in the recommended age range for screening. Although Ford had no indication that anything was amiss, he found another doctor to help him get the simple blood test.

Men with a PSA level between 4 and 10 have about a one-in-four chance of having prostate cancer. That risk goes to one in two if the level is above 10. Ford’s was 11, so high that his physician ran the test again to confirm. This time it registered a PSA of 12.

Men with a PSA level between 4 and 10 have about a one-in-four chance of having prostate cancer. That risk goes to one in two if the level is above 10.

Black men like Ford are disproportionately diagnosed with, and die from, prostate cancer, says Edward M. Schaeffer, chair of the urology department at the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine.

“I’m surprised that if you’re a Black man and you say to your doctor ‘I want to get screened for prostate cancer because I’m at higher risk’ that they would say no,” he says.

“That’s kind of shocking to me, but I do see people like Representative Ford in my clinic not that infrequently.”

Black men like Ford are disproportionately diagnosed with, and die from, prostate cancer …

“I’m surprised that if you’re a Black man and you say to your doctor ‘I want to get screened for prostate cancer because I’m at higher risk’ that they would say no,” he says.

Ford’s subsequent blood work and MRI found further irregularities, and a biopsy confirmed that he had prostate cancer.

Schaeffer performed a radical prostatectomy to remove Ford’s entire prostate gland. Months later he was declared cancer-free.

“My cancer was already in an aggressive stage. It covered a lot of my prostate, but fortunately it was still contained,” he says. “If I had not advocated for myself and waited until I was 50, it could have been too late.”

His experience illustrates two things: cancer screening can save lives, and cancer screening is not accessible for everyone who needs it.

People of color, those of low wealth and residents of rural areas tend to be most vulnerable to screening disparities for reasons that are complex and often interrelated.

Cost and lack of access, health illiteracy, implicit bias, and both cultural and structural barriers all play a role, as do disparities in cancer risk and vast differences in how screenings are integrated into patient care.

The result is that too many cancers are detected too late, leading to too many avoidable deaths.

His experience illustrates two things: cancer screening can save lives, and cancer screening is not accessible for everyone who needs it.

Cost and lack of access, health illiteracy, implicit bias, and both cultural and structural barriers all play a role, as do disparities in cancer risk and vast differences in how screenings are integrated into patient care.

The result is that too many cancers are detected too late, leading to too many avoidable deaths.

According to a report on cancer disparities from the American Association for Cancer Research, people of color receive significantly fewer recommended examinations than white people and are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced disease, lowering their chances of survival.

“Cancer screening has huge inequities in this country,” says Derek Raghavan, president of the Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte, N.C.

“The screening for breast, colon, prostate and lung cancer is way below what it should be in the African-American and Latino populations. If we could fix that, we could improve the death rate from cancer dramatically.”

“The screening for breast, colon, prostate and lung cancer is way below what it should be in the African-American and Latino populations.

ONE SIZE DOES NOT FIT ALL

Medical societies and expert panels constantly reassess their screening guidelines in response to new research, using updated models and the most recent data.

The result, however, may be confusing and seemingly inconsistent guidelines about who should be screened and how often, leaving many primary care providers unaware of the latest recommendations.

It can mean huge variations in how these screenings are implemented — among both individual physicians and large health systems — as well as in how insurance companies reimburse for them.

It can also mean huge variations in which patients receive the screenings they need.

Medical societies and expert panels constantly reassess their screening guidelines in response to new research, using updated models and the most recent data.

The result, however, may be confusing and seemingly inconsistent guidelines

It can mean huge variations in how these screenings are implemented — among both individual physicians and large health systems — as well as in how insurance companies reimburse for them.

It can also mean huge variations in which patients receive the screenings they need.

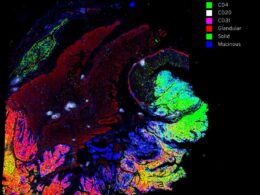

Perhaps even more concerning, researchers such as Schaeffer say, is that medical groups often have homogeneous guidelines that do not account for variations among racial groups.

With breast cancer, for instance, recent studies indicate that the incidence rate is higher in Black women younger than 45 and among white women older than 60.

Yet the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and several other medical groups do not differentiate by race and recommend mammography screenings begin at age 50 for those at average risk.

This does not acknowledge that Black women tend to have a more aggressive type of breast cancer that strikes at younger ages, argue researchers in a recent report in the Journal of Breast Imaging. For this group, those researchers recommend starting annual screening at age 40.

This does not acknowledge that Black women tend to have a more aggressive type of breast cancer that strikes at younger ages,…For this group, those researchers recommend starting annual screening at age 40.

Perhaps even more concerning, researchers such as Schaeffer say, is that medical groups often have homogeneous guidelines that do not account for variations among racial groups

“The data surrounding the disparate incidence of breast cancer in Black women under 40 is compelling and must be considered as we look at cancer screening and diagnosis through the lens of health equity,” says Monique Gary, chief medical adviser for Touch, the Black Breast Cancer Alliance and medical director of the cancer program at Grand View Health in Pennsylvania.

“The current guidelines are an example of what happens when we ‘don’t see color.’ They potentially place an already vulnerable group at significant risk for greater harm.”

Similar disparities exist in cervical cancer. In 2018 both the USPSTF and the American Cancer Society (ACS) were recommending that women between the ages of 21 and 65 get a Pap smear every three years.

Similar disparities exist in cervical cancer.

Women between 30 and 65 were advised to have both a Pap and an hrHPV test, which screens for the presence of high-risk human papillomavirus — a major risk factor for cervical cancer — every three (ACS) to five (USPSTF) years.

As though that weren’t confusing enough, the ACS changed its stance in September 2020.

Because cervical cancer is so rare in younger women, it suggested testing for hrHPV only and starting at age 25 rather than 21.

The reasoning was that getting the more accurate HPV test every five years can reduce the risk of cervical cancer more effectively than a Pap test done every three.

That is troubling for some clinicians, who attribute disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality to lower access to screening.

The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 32 percent higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnic group.

Limiting screening options could undermine cancer-prevention programs in vulnerable populations.

If the new guidelines — which increase the suggested age of first screening — are widely adopted, insurers are likely to change reimbursements to match, something that could further decrease screening rates in the most underserved communities.

The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 32 percent higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnic group.

Limiting screening options could undermine cancer-prevention programs in vulnerable populations.

That is troubling for some clinicians, who attribute disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality to lower access to screening.

As Ford discovered last fall, screening guidelines strongly influence who gets referred for screening and what tests insurance providers will cover for whom.

The trouble is that those guidelines are based on clinical trials conducted with subjects who are predominantly white.

screening guidelines strongly influence who gets referred for screening and what tests insurance providers will cover for whom.

The trouble is that those guidelines are based on clinical trials conducted with subjects who are predominantly white.

Research shows that Black people are at a higher risk of lung cancer even if they smoke less over time, and their inclusion in clinical trials could have a significant impact on any screening guidelines that result.

Raghavan points to the 2011 National Lung Cancer Screening trial, which studied more than 53,000 current or former heavy smokers to determine the cost and effectiveness of a form of screening called low-dose computed tomography (LDCT).

Fewer than 5 percent of their participants were Black.

A European trial on the same topic, the NELSON lung cancer study, also studied LDCT screening with 7,557 participants. The researchers made no mention of people of African ancestry.

Research shows that Black people are at a higher risk of lung cancer even if they smoke less over time, and their inclusion in clinical trials could have a significant impact on any screening guidelines that result.

In the 2011 National Lung Cancer Screening trial,…fewer than 5 percent of their participants were Black. In The European trial on the same topic, the NELSON lung cancer study,…the researchers made no mention of people of African ancestry.

Clinical trials investigating the benefits of prostate cancer screening also excluded Black men, despite greater incidence and mortality in this population.

These trials, which consisted exclusively of white men, showed little or no benefit from PSA screening.

As a result, in 2012 the USPSTF — concerned about overdiagnosis and treatment of small, benign or slow-growing cancers — recommended against using prostate cancer screening for anyone.

The organization partially reversed its decision in 2018, recommending instead that for men age 55 to 69, screening decisions should be left up to the individual.

Clinical trials investigating the benefits of prostate cancer screening also excluded Black men, despite greater incidence and mortality in this population.

But some researchers are finally beginning to acknowledge the importance of diversity both in clinical trial participation and in establishing more relevant screening guidelines.

A 2019 study in JAMA Oncology found that fewer Black smokers with lung cancer met the criteria for screening than white smokers with the disease.

That is because Black smokers develop lung cancer at younger ages and at higher rates than white smokers.

The researchers found that 68 percent of Black smokers were ineligible for screening at the time of their diagnosis, whereas 44 percent of white smokers were.

But some researchers are finally beginning to acknowledge the importance of diversity both in clinical trial participation and in establishing more relevant screening guidelines.

A 2019 study in JAMA Oncology found that fewer Black smokers with lung cancer met the criteria for screening than white smokers with the disease.

That is because Black smokers develop lung cancer at younger ages and at higher rates than white smokers.

The USPSTF cited the study earlier this year as a factor in lowering its recommended screening age for lung cancer, from age 55 to 50, and reducing the number of pack years (years of smoking multiplied by the number of packs smoked per day) from 30 to 20, greatly expanding potential access.

Nevertheless, only 5.7 percent of those at high risk are actually screened, in part because of the dearth of screening centers and lack of awareness.

The USPSTF cited the study earlier this year as a factor in lowering its recommended screening age for lung cancer, from age 55 to 50, and reducing the number of pack years (years of smoking multiplied by the number of packs smoked per day) from 30 to 20, greatly expanding potential access.

Nevertheless, only 5.7 percent of those at high risk are actually screened, in part because of the dearth of screening centers and lack of awareness.

Originally published at https://www.scientificamerican.com

Names mentioned

Edward M. Schaeffer, chair of the urology department at the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine.

Derek Raghavan, president of the Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte, N.C.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

Monique Gary, chief medical adviser for Touch, the Black Breast Cancer Alliance and medical director of the cancer program at Grand View Health in Pennsylvania.