The New York Times

July 18th, 2021

IBM’s artificial intelligence was supposed to transform industries and generate riches for the company. Neither has panned out.

Now, IBM has settled on a humbler vision for Watson.

A decade ago, IBM’s public confidence was unmistakable. Its Watson supercomputer had just trounced Ken Jennings, the best human “Jeopardy!” player ever, showcasing the power of artificial intelligence. This was only the beginning of a technological revolution about to sweep through society, the company pledged.

“Already,” IBM declared in an advertisement the day after the Watson victory, “we are exploring ways to apply Watson skills to the rich, varied language of health care, finance, law and academia.”

But inside the company, the star scientist behind Watson had a warning: Beware what you promise.

David Ferrucci, the scientist, explained that Watson was engineered to identify word patterns and predict correct answers for the trivia game.

It was not an all-purpose answer box ready to take on the commercial world, he said. It might well fail a second-grade reading comprehension test.

His explanation got a polite hearing from business colleagues, but little more.

“It wasn’t the marketing message,” recalled Mr. Ferrucci, who left IBM the following year.

It was, however, a prescient message.

IBM poured many millions of dollars in the next few years into promoting Watson as a benevolent digital assistant that would help hospitals and farms as well as offices and factories. The potential uses, IBM suggested, were boundless, from spotting new market opportunities to tackling cancer and climate change. An IBM report called it “the future of knowing.”

IBM’s television ads included playful chats Watson had with Serena Williams and Bob Dylan. Watson was featured on “60 Minutes.” For many people, Watson became synonymous with A.I.

And Watson wasn’t just going to change industries. It was going to breathe new life into IBM — a giant company, but one dependent on its legacy products. Inside IBM, Watson was thought of as a technology that could do for the company what the mainframe computer once did — provide an engine of growth and profits for years, even decades.

Watson has not remade any industries. And it hasn’t lifted IBM’s fortunes. The company trails rivals that emerged as the leaders in cloud computing and A.I. — Amazon, Microsoft and Google. While the shares of those three have multiplied in value many times, IBM’s stock price is down more than 10 percent since Watson’s “Jeopardy!” triumph in 2011.

The company’s missteps with Watson began with its early emphasis on big and difficult initiatives intended to generate both acclaim and sizable revenue for the company, according to many of the more than a dozen current and former IBM managers and scientists interviewed for this article. Several of those people asked not to be named because they had not been authorized to speak or still had business ties to IBM.

Manoj Saxena, a former general manager of the Watson business, said that the original objective — to do pioneering work that was good for society — was laudable. It just wasn’t realistic.

“The challenges turned out to be far more difficult and time-consuming than anticipated,” said Mr. Saxena, who is now executive chairman of Cognitive Scale, an A.I. start-up whose investors include IBM.

Martin Kohn, a former chief medical scientist at IBM Research, recalled recommending using Watson for narrow “credibility demonstrations,” like more accurately predicting whether an individual will have an adverse reaction to a specific drug, rather than to recommend cancer treatments.

“I was told I didn’t understand,” Dr. Kohn said.

The company’s top management, current and former IBM insiders noted, was dominated until recently by executives with backgrounds in services and sales rather than technology product experts. Product people, they say, might have better understood that Watson had been custom-built for a quiz show, a powerful but limited technology.

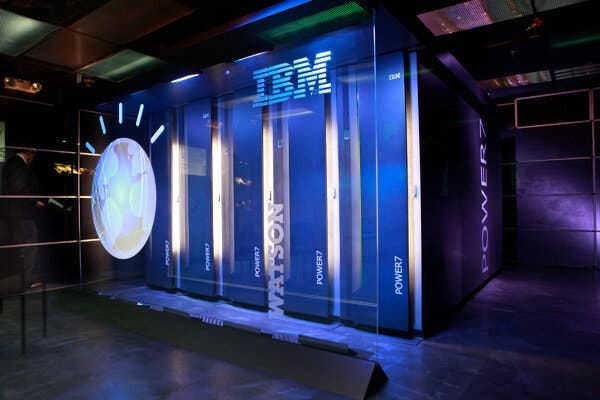

Watson, ready for its “Jeopardy!” appearance, in 2011. Credit… Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times

IBM describes Watson as a learning journey for the company. There have been wrong turns and setbacks, IBM says, but that comes with trying to commercialize pioneering technology.

“Innovation is always a process,” said Rob Thomas, the executive in charge of the Watson business in the past few years. Mr. Thomas, who earlier this month was named senior vice president for global sales, sees the A.I. development at IBM in three stages: the technical achievement with “Jeopardy!,” the years of “experimentation” with big services contracts and, now, a shift to a product business.

IBM insists that its revised A.I. strategy — a pared-down, less world-changing ambition — is working. The job of reviving growth was handed to Arvind Krishna, a computer scientist who became chief executive last year, after leading the recent overhaul of IBM’s cloud and A.I. businesses.

But the grand visions of the past are gone. Today, instead of being a shorthand for technological prowess, Watson stands out as a sobering example of the pitfalls of technological hype and hubris around A.I.

The march of artificial intelligence through the mainstream economy, it turns out, will be more step-by-step evolution than cataclysmic revolution.

Time and again during its 110-year history, IBM has ushered in new technology and sold it to corporations. The company so dominated the market for mainframe computers that it was the target of a federal antitrust case. PC sales really took off after IBM entered the market in 1981, endorsing the small machines as essential tools in corporate offices. In the 1990s, IBM helped its traditional corporate customers adapt to the internet.

IBM executives came to see A.I. as the next wave to ride.

Mr. Ferrucci first pitched the idea of Watson to his bosses at IBM’s research labs in 2006. He thought building a computer to tackle a question-answer game could push science ahead in the A.I. field known as natural language processing, in which scientists program computers to recognize and analyze words. Another research goal was to advance techniques for automated question answering.

After overcoming initial skepticism, Mr. Ferrucci assembled a team of scientists — eventually more than two dozen — who worked out of the company’s lab in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., about 20 miles north of IBM’s headquarters in Armonk.

The Watson they built was a room-size supercomputer with thousands of processors running millions of lines of code. Its storage disks were filled with digitized reference works, Wikipedia entries and electronic books. Computing intelligence is a brute force affair, and the hulking machine required 85,000 watts of power. The human brain, by contrast, runs on the equivalent of 20 watts.

All along, the company’s goal was to push the frontiers of science and burnish IBM’s reputation. IBM made a similar — and successful — bet with its chess-playing Deep Blue computer, which beat the world chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1997. In a nod to the earlier project, the scientists originally called their A.I. computer DeepJ! But the marketers stepped in and decided to name the machine for IBM’s founder, Thomas Watson Sr.

When Watson triumphed at “Jeopardy!,” the response was overwhelming. IBM’s customers clamored for one of their own. Executives saw a big business opportunity.

Clearly, there was a market for Watson. But there was a problem.

IBM had little to sell.

Executives got to work figuring out how to turn a business out of its new star. One possibility kept coming up: health care.

Health care is the nation’s largest industry and spending is rising worldwide. It is a field rich in data, the essential fuel for modern A.I. programs. And the social benefit is undeniable — the promise of longer, healthier lives.

Ginni Rometty, IBM’s chief executive at the time, described the big bet on health care as the next chapter in the company’s heritage of tackling grand challenges, from counting the census to helping guide the Apollo 11 mission to the moon.

“Our moon shot will be the impact we have on health care,” Ms. Rometty said. “I’m absolutely positive about it.”

IBM started with cancer. It sought out medical centers where researchers worked with huge troves of data. The idea was that Watson would mine and make sense of all that medical information to improve treatment.

At the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, one of IBM’s partners, the difficulties soon became apparent. The oncologists, having seen Watson’s “Jeopardy!” performance, assumed it was an answer machine. The IBM technologists were frustrated by the complexity, messiness and gaps in the genetic data at the cancer center.

“We thought it would be easy, but it turned out to be really, really hard,” said Dr. Norman Sharpless, former head of the school’s cancer center, who is now the director of the National Cancer Institute. “We talked past each other for about a year.”

Eventually, the oncologists and technologists found an approach that suited Watson’s strength — quickly ingesting and reading many thousands of medical research papers. By linking mentions of gene mutations in the papers with a patient’s genetic profile, Watson could sometimes point to other treatments the physicians might have missed. It was a potentially useful new diagnostic tool.

But it turned out to be not useful or flexible enough to be a winning product. At the end of last year, IBM discontinued Watson for Genomics, which grew out of the joint research with the University of North Carolina. It also shelved another cancer offering, Watson for Oncology, developed with another early collaborator, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Another cancer project, called Oncology Expert Advisor, was abandoned in 2016 as a costly failure. It was a collaboration with the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. The aim was to create a bedside diagnostic tool that would read patients’ electronic health records, volumes of cancer-related scientific literature and then make treatment recommendations.

The problems were numerous. During the collaboration, MD Anderson switched to a new electronic health record system and Watson could not tap patient data. Watson struggled to decipher doctors’ notes and patient histories, too.

Physicians grew frustrated, wrestling with the technology rather than caring for patients. After four years and spending $62 million, according to a public audit, MD Anderson shut down the project.

“They chose the highest bar possible, real-time cancer diagnosis, with an immature technology,” said Shane Greenstein, a professor and co-author of a recent Harvard Business School case study on the Watson project at MD Anderson. “It was such a high-risk path.”

IBM continued to invest in the health industry, including billions on Watson Health, which was created as a separate business in 2015. That includes more than $4 billion to acquire companies with medical data, billing records and diagnostic images on hundreds of millions of patients. Much of that money, it seems clear, they are never going to get back.

Now IBM is paring back Watson Health and reviewing the future of the business. One option being explored, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal, is to sell off Watson Health.

Many outside researchers long dismissed Watson as mainly a branding campaign. But recently, some of them say, the technology has made major strides.

In an analysis done for The New York Times, the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence compared Watson’s performance on standard natural language tasks like identifying persons, places and the sentiment of a sentence with the A.I. services offered by the big tech cloud providers — Amazon, Microsoft and Google.

Watson did as well as, and sometimes better than, the big three. “I was quite surprised,” said Oren Etzioni, chief executive of the Allen Institute. “IBM has gotten its act together, certainly in these capabilities.”

The business side of Watson also shows signs of life. Now, Watson is a collection of software tools that companies use to build A.I.-based applications — ones that mainly streamline and automate basic tasks in areas like accounting, payments, technology operations, marketing and customer service. It is workhorse artificial intelligence, and that is true of most A.I. in business today.

A core Watson capability is natural language processing — the same ability that helped power the “Jeopardy!” win. That technology powers IBM’s popular Watson Assistant, used by businesses to automate customer service inquiries.

The company does not report financial results for Watson. But Mr. Thomas, who now leads worldwide sales for IBM, points to signs of success.

It is early for A.I. in the corporate market, he said, the market opportunity will be huge and the key at this stage is to hasten adoption of the Watson software offerings.

IBM says it has 40,000 Watson customers across 20 industries worldwide, more than double the number four years ago. Watson products and services are being used 140 million times a month, compared with a monthly rate of about 10 million two years ago, IBM says. Some of the big customers are in health, like Anthem, a large insurer, which uses Watson Assistant to automate customer inquiries.

“Adoption is accelerating,” Mr. Thomas said.

Five years ago, Watson, a nerdy, disembodied voice from the A.I. future, chatted and joked in advertisements with the tennis superstar Serena Williams. Today, the TV ads proclaim the technology’s potential to save time and work in offices and on factory floors.

Watson, one TV ad says, helps companies “automate the little things so they can focus on the next big thing.”

The contrast in ambition seems striking. That’s fine with IBM. Watson is no longer the next big thing, but it may finally become a solid business for IBM.

Originally published at https://www.nytimes.com on July 16, 2021.