THE HEALTH ARGUMENT FOR CLIMATE ACTION

In memory of Ella Kissi-Debrah — and all other children who have suffered and died from air pollution and climate change.

World Health Organization

October, 2021

Nigel Topping, COP26 High-Level Climate Action Champion

The development and production of this report were led by Arthur Wyns, Marina Maiero, Alexandra Egorova and Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum from the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health, WHO.

Foreword

Extreme heat, floods, droughts, wildfires and hurricanes: 2021 has broken many records. The climate crisis is upon us, powered by our addiction to fossil fuels. The consequences for our health are real and often devastating.

Climate change impacts health in all countries, but it hits people in low- and middle-income countries the hardest, especially small island developing states, whose very existence is under threat from rising sea levels. Any delay in acting on this global health threat will disproportionately affect the most disadvantaged around the world. The COVID-19 pandemic is a visceral example of the inequitable impacts of such a global threat. To fully address the urgency of both these crises, we need to confront the inequalities that lie at the root of so many global health challenges.

Health and equity are central to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement and to making COP26 a success. Protecting health requires action well beyond the health sector, in energy, transport, nature, food systems, finance and more. The ten recommendations outlined in this report — and the action points, resources and case studies that support them — provide concrete examples of interventions that, with support, can be scaled up rapidly to safeguard our health and our climate.

The recommendations are the result of extensive consultations with health professionals, organizations and stakeholders worldwide, and represent a broad consensus statement urging governments to act to tackle the climate crisis, restore biodiversity, and protect health.

Putting that into practice means investing in a healthier, fairer, and more resilient world. Advanced economies, in particular, have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to demonstrate true global solidarity, both in supporting an equitable response to COVID-19, and by making health central to the implementation of the renewed climate commitments that they are making at COP26. It is the only way for us to get out of the current health crisis and prevent future ones.

The health arguments for rapid climate action have never been clearer. I hope this report can guide policymakers and practitioners from across sectors and across the world to implement the transformative changes needed.

Let’s get to work.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

Director-General

World Health Organization

Foreword

As the last two years have shown us, public, planetary and economic health are inextricably linked. The race to a zero-emissions economy before 2050 is, therefore, a race to a healthy, clean and resilient future.

The race to a zero-emissions economy before 2050 is … a race to a healthy, clean and resilient future.

As highlighted by the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report published earlier this year, we need to halve greenhouse gas emissions between 2020 and 2030 while reversing nature loss in order to reach net zero and limit global warming to a 1.5°C.

But time is running short, and every fraction of a degree threatens to cause more death and economic destruction.

This is going to require full systems change and collaboration across all sectors.

- As highlighted by this report, these include energy, transport, built environment and agriculture amongst multiple other sectors.

- However, we also need to act within the healthcare sector given the scale of the economy and emissions it represents.

The World Health Organization estimates that globally the spending on health reached 10% of GDP in 2018, and Health Care Without Harm estimates that in 2019 the sector was responsible for 4.4% of net global emissions.

… in 2019 the sector was responsible for 4.4% of net global emissions.

- We have seen good progress to date on the UN Race to Zero, where 46 healthcare institutions representing over 3,200 healthcare facilities across 18 countries have joined.

- In addition to this, over 28% of major pharmaceutical and medical technology companies by revenue have joined the campaign.

But we need to keep accelerating our efforts to both cut emissions and build resilience to the impacts of climate change, and move from ambition to action within the 2020s.

As the healthcare sector is already demonstrating, health can enable transformational change in other sectors.

At the same time, we must adapt to thrive in spite of impacts such as floods, droughts and extreme temperatures.

Through the UN Race to Resilience, by 2030 we are mobilising businesses, investors, cities and regions to build the resilience of the 4 billion people most at risk.

On top of that, we need to continue to improve the quality and delivery of accessible healthcare across the globe.

The future of healthcare needs to be reimagined, where we can build a world that is zero carbon, resilient, and healthy for all.

The future of healthcare needs to be reimagined, where we can build a world that is zero carbon, resilient, and healthy for all.

In this future, there is clean air, food security, more access to nature — a world where our children can thrive. I welcome the clear recommendations from this report which show the steps we must take together to build that future.

In this future, there is clean air, food security, more access to nature — a world where our children can thrive.

Nigel Topping

COP26 High-Level Climate Action Champion

Executive Summary

The 10 recommendations in the COP26 Special Report on Climate Change and Health propose a set of priority actions from the global health community to governments and policy makers, calling on them to act with urgency on the current climate and health crises.

The recommendations were developed in consultation with over 150 organisations and 400 experts and health professionals. They are intended to inform governments and other stakeholders ahead of the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and to highlight various opportunities for governments to prioritise health and equity in the international climate movement and sustainable development agenda. Each recommendation comes with a selection of resources and case studies to help inspire and guide policymakers and practitioners in implementing the suggested solutions.

The next few years present a crucial window for governments to integrate health and climate policies in their COVID-19 recovery packages (recommendation 1) and international climate commitments (recommendation 2). While nearterm pandemic responses will largely set the pace and direction of health and climate goals, ambitious national climate commitments will be crucial to sustain a healthy recovery in the mid- to long-term. To achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, health and equity need to be placed at the centre of the United Nations climate negotiations going forward.

The health benefits from climate actions (recommendation 3) are well documented and offer strong arguments for transformative change — and this is true across many priority areas for action: adaptation and resilience (recommendation 4), the energy transition (recommendation 5), clean transport and active mobility (recommendation 6), nature (recommendation 7), food systems (recommendation 8) and finance (recommendation 9). The health sector and health community are a trusted and influential — but often overlooked — climate actor that can enable transformational change to protect people and planet (recommendation 10).

Recommendations on climate change and health:

- Commit to a healthy recovery.

Commit to a healthy, green, and just recovery from COVID-19. - Our health is not negotiable.

Place health and social justice at the heart of the UN climate talks. - Harness the health benefits of climate action.

Prioritise those climate interventions with the largest health-, social- and economic gains. - Build health resilience to climate risks.

Build climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable health systems and facilities, and support health adaptation and resilience across sectors. - Create energy systems that protect and improve climate and health.

Guide a just and inclusive transition to renewable energy to save lives from air pollution, particularly from coal combustion. End energy poverty in households and health care facilities. - Reimagine urban environments, transport, and mobility.

Promote sustainable, healthy urban design and transport systems, with improved land-use, access to green and blue public space, and priority for walking, cycling and public transport. - Protect and restore nature as the foundation of our health.

Protect and restore natural systems, the foundations for healthy lives, sustainable food systems and livelihoods. - Promote healthy, sustainable, and resilient food systems.

Promote sustainable and resilient food production and more affordable, nutritious diets that deliver on both climate and health outcomes. - Finance a healthier, fairer, and greener future to save lives.

Transition towards a wellbeing economy. - Listen to the health community and prescribe urgent climate action. Mobilise and support the health community on climate action.

The health impacts of climate change

Climate change is the single biggest health threat facing humanity[1], and health professionals worldwide are already responding to the health harms caused by this unfolding crisis[2].

Climate change is the single biggest health threat facing humanity[1], and health professionals worldwide are already responding to the health harms caused by this unfolding crisis[2].

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has concluded that to avert catastrophic health impacts and prevent millions of climate change-related deaths, the world must limit temperature rise to 1.5°C[3].

Past emissions have already made a certain level of global temperature rise and other changes to the climate inevitable.

Global heating of even 1.5°C is not considered safe, however; every additional tenth of a degree of warming will take a serious toll on people’s lives and health[4].

While no one is safe from these risks, the people whose health is being harmed first and worst by the climate crisis are the people who contribute least to its causes, and who are least able to protect themselves and their families against it — people in low-income and disadvantaged countries and communities[5].

The climate crisis threatens to undo the last fifty years of progress in development, global health, and poverty reduction, and to further widen existing health inequalities between and within populations[6] (6).

It severely jeopardises the realisation of universal health coverage (UHC) in various ways — including by compounding the existing burden of disease and by exacerbating existing barriers to accessing health services, often at the times when they are most needed[7] (7).

Over 930 million people — around 12% of the world’s population — spend at least 10% of their household budget to pay for health care.

With the poorest people largely uninsured, health shocks and stresses already currently push around 100 million people into poverty every year, with the impacts of climate change worsening this trend[8] [9].

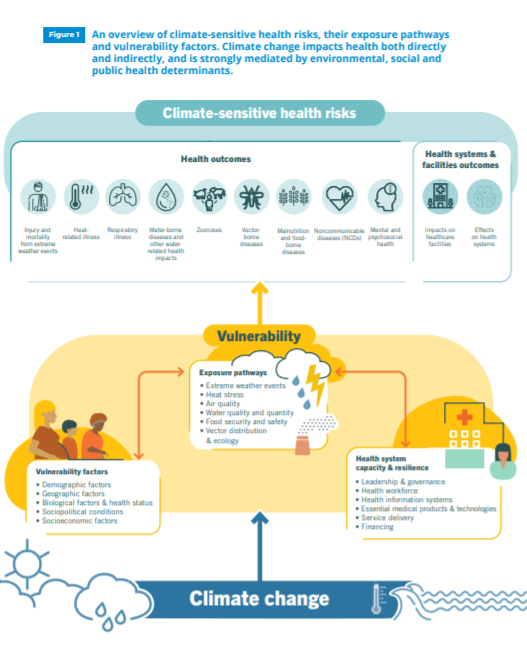

Climate change is already impacting health in a myriad of ways, including by leading to death and illness from increasingly frequent extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, storms and floods, the disruption of food systems, increases in zoonoses and food-, water- and vector-borne diseases, and mental health issues.

Furthermore, climate change is undermining many of the social determinants for good health, such as livelihoods, equality and access to health care and social support structures (Figure 1).

These climate-sensitive health risks are disproportionately felt by the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, including women, children, ethnic minorities, poor communities, migrants or displaced persons, older populations, and those with underlying health conditions[10] [11].

Although it is unequivocal that climate change affects human health, it remains challenging to accurately estimate the scale and impact of many climate-sensitive health risks. However, scientific advances progressively allow us to attribute an increase in morbidity and mortality to human-induced warming[12], and more accurately determine the risks and scale of these health threats[13].

In the short- to medium-term, the health impacts of climate change will be determined mainly by the vulnerability of populations, their resilience to the current rate of climate change and the extent and pace of adaptation[14].

In the longer-term, the effects will increasingly depend on the extent to which transformational action is taken now to reduce emissions and avoid the breaching of dangerous temperature thresholds and potential irreversible tipping points[15].

Figure 1 An overview of climate-sensitive health risks, their exposure pathways and vulnerability factors. Climate change impacts health both directly and indirectly, and is strongly mediated by environmental, social and public health determinants.

The health argument for climate action

Taking rapid and ambitious action to halt and reverse the climate crisis has the potential to bring many benefits, including for health.

Co-benefits are defined as: the positive effects that a policy or measure aimed at one objective might have on other objectives, thereby increasing the total benefits for society or the environment[16].

The public health benefits resulting from ambitious mitigation efforts would far outweigh their cost[17].

Strengthening resilience and building adaptive capacity to climate change, on the other hand, can also lead to health benefits by protecting vulnerable populations from disease outbreaks and weather-related disasters, by reducing health costs and by promoting social equity.

The health co-benefits from climate change actions are well evidenced, offer strong arguments for transformative change, and can be gained across many sectors, including in energy generation, transport, food and agriculture, housing and buildings, industry, and waste management[18] [19].

For example, many of the same actions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions also improve air quality, and support synergies with many of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)[20] (16).

Some measures — such as facilitating walking and cycling — improve health through increased physical activity, resulting in reductions in respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, some cancers, diabetes and obesity[21].

Another example is the promotion of urban green spaces, which facilitate climate mitigation and adaptation while also offering health co-benefits, such as reduced exposure to air pollution, local cooling effects, stress relief, and increased recreational space for social interaction and physical activity[22] [23].

A shift to more nutritious plant-based diets in line with WHO recommendations, as a third example, could reduce global emissions significantly, ensure a more resilient food system, and avoid up to 5.1 million diet-related deaths a year by 2050[24].

Research has shown that climate action aligned with Paris Agreement targets would save millions of lives due to improvements in air quality, diet and physical activity, among other benefits[25].

However, many climate decision-making processes currently do not account for health co-benefits and their economic valuation.

The 2021 WHO Health and Climate Change Global Survey of governments found that less than 1 in 5 countries have conducted an assessment of the health co-benefits of national climate mitigation policies[26], while a 2021 WHO review of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) found just 13% of current NDCs commit to quantifying or monitoring the health co-benefits of climate policies or targets[27].

… only 1 in 5 countries have conducted an assessment of the health co-benefits of national climate mitigation policies

While there are significant health co-benefits available for various climate interventions, which can act as important ethical and economic incentives, some climate mitigation and adaptation policies may not maximise health gains or may potentially cause harm.

Additionally, several challenges and barriers remain for the comprehensive inclusion of health in the cost assessment of climate policies[28].

It is therefore critical that health and other experts are fully involved in climate decision-making processes at all levels, to ensure health and equity considerations are well understood and accounted for when developing climate policies[29].

WHO Expert Working Group on the Health Benefits of Climate Change Mitigation

In recognition of the growing field of research on the public health gains of climate change mitigation, and the importance of this evidence to catalyse global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, WHO has established an Expert Working Group on the Health Benefits of Climate Change Mitigation as part of its Global Air Pollution and Health Technical Advisory Group (GAPH-TAG).

The Working Group brings together global experts to review and advise on actions that both address climate change and improve human health, primarily through improved air quality. As part of its work, the GAPH-TAG will provide guidance and tools to national stakeholders to carry out assessments of the health benefits or harms associated with interventions to reduce carbon emissions.

By emphasising the health implications of climate mitigation policies and providing recommendations on best practices, the initiative will empower national health policymakers to elevate the health argument for ambitious climate action, and ensure health is represented in national and global planning processes[30].

Case study

Building a healthy, resilient future in Small Island Developing States

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) face a particular set of urgent health threats. They are uniquely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, making up two thirds of the countries that suffer the highest relative losses from climate disasters each year. At the same time, they carry heavy burdens of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), malnutrition, and now also the impacts of COVID-19. Together these threats are contributing to unprecedented economic, and even existential, crises for these States. Most SIDS are classified economically as middle-income or above, though they face severe economic vulnerabilities and lack access to external support relative to their needs[31].

In the face of all these challenges, SIDS have shared strengths. They are leaders in the international negotiations on climate change, have well-established regional support mechanisms and collaborative bodies, and have a rich history of commitment to health and sustainable development[32].

Any effort to ensure a healthy future for SIDS must allow their people to survive and thrive by reducing global carbon emissions to mitigate climate impacts. It must also strengthen the resilience of health systems and health-determining sectors, such as food and nutrition, water and sanitation, and social protection, to protect and enhance the health and wellbeing of the people of SIDS in the face of a changing climate.

WHO launched a Special Initiative on Climate Change and Health in SIDS at the 23rd Conference of the Parties (COP23) of the UNFCCC held in Bonn in 2017, in collaboration with the UNFCCC Secretariat and the Fijian Presidency of the COP23[33]. WHO, with SIDS Member States, developed a Global Plan of Action, which sets out key actions to ensure all health systems in SIDS will be resilient to climate change by 2030[34]. The SIDS have been among the leaders globally in assessing risks and setting national agendas for climate change and health[35].

WHO is reinforcing its strategic actions to support SIDS in addressing their top health threats. In June 2021, WHO hosted a SIDS Summit for Health that brought together SIDS heads of states, ministers of health, and others, to frame priority actions and intensify collaboration.

In the outcome statement of the Summit, the representatives of SIDS put forward their commitments and calls to action to achieve a healthy, resilient future in SIDS[36]. These include fully addressing health in the climate change movement, scaling up integrated care for NCDs and mental health needs, enabling healthy diets and biodiversity, pursuing equity in access to vaccines and other innovations, more equitable and resilient health systems, stronger workforces and supply systems, as well as sustainable financing for climate and health goals. They called for WHO to support a SIDS Leaders Group for Health and SIDS Voices for Health Forum, to amplify SIDS voices, promote collaborative action and galvanise targeted support[37].

The efforts of SIDS highlight that governments can put forward a joint vision for health and development that addresses the acute needs of this critical time, prioritising the most vulnerable and disadvantaged regions and communities.

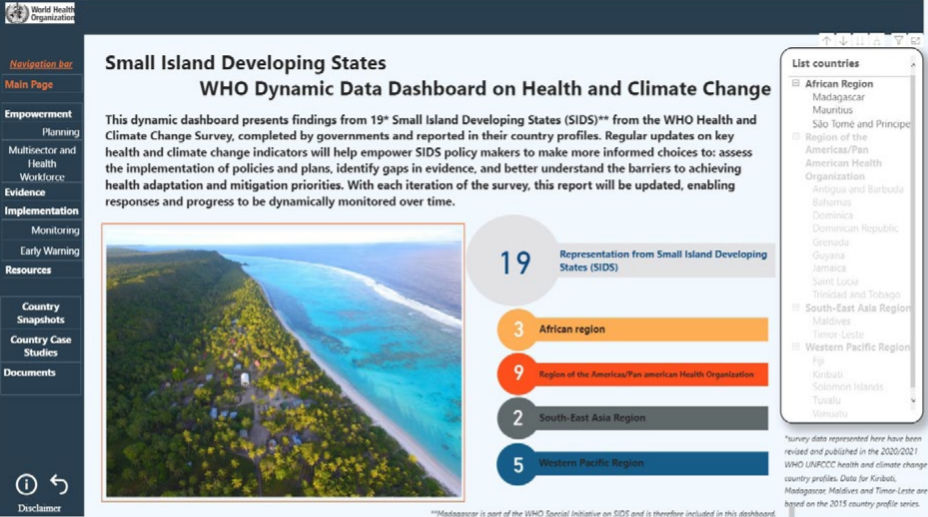

Monitoring the progress and barriers on climate change and health in SIDS

The Health and Climate Change Country Profiles, developed by WHO and the UNFCCC Secretariat, are a key mechanism in WHO’s efforts to monitor national progress on health and climate change. Country profiles are prepared in collaboration with ministries of health and other partners such as ministries of the environment and national meteorological services. They allow countries to strengthen their national evidence base for decision-making and measure progress in building climate-resilient health systems. Close to 100 country profiles have been developed, including for many SIDS.

As part of WHO’s monitoring efforts and the WHO Special Initiative on Climate Change and Health in SIDS, a series of SIDS country profiles were created, illustrating the progress made by island states to date in responding to the health threats of climate change. A dynamic data dashboard visualises the country profile data and allows SIDS policy makers to monitor key health and climate change indicators, including to assess the implementation of policies and plans, identify gaps in evidence, and better understand the barriers to achieving health adaptation and mitigation priorities, including for implementation and monitoring.

Recommendations for climate change and health

The recommendations outlined in the COP26 Special Report have been developed by health professionals, organisations and stakeholders worldwide, and represent a broad consensus statement by the global health community on the actions that are needed to tackle the climate crisis, restore biodiversity, and protect health.

The recommendations were developed in consultation with over 150 organisations and over 400 experts and health professionals, through a series of consultations and workshops in all six WHO regions. They are intended to inform governments and other stakeholders ahead of the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

COP26 is considered a crucial moment for the world’s governments to commit to collective action on limiting climate change. The conference aims to operationalise the Paris Agreement on climate change, and Parties to the agreement are expected to bring forward national climate plans reflecting their highest possible ambition.

The ten recommendations, and their respective action points, highlight the urgent need and numerous opportunities for governments to prioritise health and equity in the international climate movement and the sustainable development agenda. Each recommendation is accompanied by a selection of resources and case studies to help inspire and guide policymakers and practitioners in implementing the proposed solutions.

Acknowledgements

The World Health Organization (WHO) would like to express its gratitude to all Member States, organizations and individuals that participated in the WHO Regional Consultations on Climate Change and Health. These consultations were hosted by the WHO Civil Society Working Group to Advance Action on Climate Change, co-chaired by WHO and the Global Climate and Health Alliance, and in partnership with WHO regional offices and other health partners. The generous contributions of all the participants to the consultations were essential in developing the recommendations contained in this report.

The development and production of this report were led by Arthur Wyns, Marina Maiero, Alexandra Egorova and Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum from the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health, WHO.

More than 150 organizations and 400 experts and practitioners contributed to this report through participation in workshops, peer review and the provision of insights and text.

For the complete list of acknowledgments, refer to the full publication.

References

See the original publication

Suggested citation

COP26 special report on climate change and health: the health argument for climate action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

Originally published at https://www.who.int