This is an excerpt of the white paper “The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2022”, with the title above, focusing on the topic in question.

Trust for America’s Health (FHAH)

Matt McKillop, MPP

Dara Alpert Lieberman, MPP

July 2022

Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public health policy, research, and advocacy organization that promotes optimal health for every person and community, and makes the prevention of illness and injury a national priority.

Executive Summary excerpt by:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

health transformation . institute

health economics unit

July 29, 2022

Executive Summary

Public health funding has not kept pace with public health needs. Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) has joined numerous leaders within the public health community in calling for an annual $4.5 billion investment in public health infrastructure at the state, local, tribal, and territorial levels.

As the world grapples with the third year of addressing the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is clear that while a number of factors — including misinformation, political division, and health inequities — caused the tragic impact of the pandemic, underfunding of the public health system was also a large contributor.

As the pandemic has illustrated, chronic underfunding of public health at both the federal and state levels has left the country ill-prepared for public health emergencies and impedes prevention of many of the major causes of illness and death in the United States.

Today, the public health infrastructure relies on

· antiquated data systems,

· understaffed departments,

· insufficient plans, and

· inadequate supplies of the medical countermeasures needed during an infectious disease outbreak or some other public health emergency.

Investments in public health are needed everywhere, particularly for people living in those communities — estimated to be about half of all U.S. residents — not currently protected by a comprehensive public health system.[1]

As Americans navigate the next stages of the pandemic and beyond, it is critical that the nation invest in:

· modernizing the public health data infrastructure,

· grow and further diversify the public health workforce,

· reduce health inequities, and

· address the social determinants of health (SDOH) that can either drive or limit a person’s ability to attain good health.

Underinvestment in health equity and SDOH contributes to high rates of chronic disease, which left certain population groups — including many communities of color, rural communities, and older adults — more vulnerable to severe health outcomes during the pandemic.[2]

The incidence of chronic diseases, including obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, has increased in many communities, in part due to health departments that lack the required resources to deliver prevention programs or that have cut programs for obesity and diabetes prevention altogether.

At the national level, the country spent $4.1 trillion on health in 2020, but only 5.4 percent of that spending targeted public health and prevention.

At the national level, the country spent $4.1 trillion on health in 2020, but only 5.4 percent of that spending targeted public health and prevention.

Notably, this share nearly doubled in 2020 (from 2.8 percent in 2019) due to significant infusions of short-term, emergency funding to respond to the pandemic.[3] [4]

However, if history holds true, these infusions of emergency response dollars are an anomaly and public health funding will again return to insufficient levels. This is a pattern that must change.

For over two decades, this report has tracked public health funding at federal, state, and local levels and has recommended policy actions to improve Americans’ health security.

During that time, TFAH has documented a chronic pattern of underfunding of vital public health programs and protections. Investments in public health that if made can be leveraged during an emergency.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made that underfunding and its deadly consequences abundantly clear, but infectious disease outbreaks are not the only risk.

For instance,

· over the past two years, many parts of the country experienced record-setting heat waves, wildfires, storms, and flooding,[5] and

· the nation saw historic increases in alcohol, drug, and suicide deaths,[6] all of which taxed a public health system already severely stressed by the pandemic.

Often, in order to respond to the pandemic, health departments had to pull staff and resources away from other critical work, including work focused on chronic disease prevention, childhood vaccinations, tobacco prevention and cessation programs, maternal and child health programs, HIV prevention, and behavioral health.

Mixed picture for recent funding

See the appendix (below)

WHY INVEST IN PUBLIC HEALTH?

The United States spends trillions of dollars annually on healthcare, but U.S. residents are not getting healthier and tend to experience worse health outcomes than residents of other high-income countries that spend comparably less money.[15] [16]

One reason is America’s lack of investment in programs to prevent illness.

Nearly half of all U.S. residents ages 55 or older have two or more chronic health conditions.[17]

Yet funding for CDC’s chronic disease prevention programs remains inadequate, as most funding lines do not receive enough funding to reach all states.

In addition, lack of attention to and investment in the SDOH (Social Determinants of Health) — factors such as where people are born, live, work, and age as well as their access to safe housing, jobs, quality education, and healthcare — exacerbate health inequities and increase the costs associated with treating preventable illness.

For example, there is strong evidence that public health programs focused on disease prevention and improving community health, including childhood vaccination and tobacco-cessation programs, can reduce these costs.[18] [19]

Increased funding for public health programs is an investment in less healthcare spending.

For example, there is strong evidence that public health programs focused on disease prevention and improving community health, including childhood vaccination and tobacco-cessation programs, can reduce these costs

WHAT ARE THE CORE CAPABILITIES OF A ROBUST PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM?

Keeping U.S. residents safe from diseases, disasters, the health impacts of climate change, and bioterrorism requires a public health system focused on prevention, equity, preparedness, and surveillance.

Investment to ensure foundational capabilities is key. Interagency and jurisdictional planning and cooperation are also critical, as are efforts to address the needs of population groups or communities at greatest risk.

All of these activities require dedicated and sustained funding and a well-resourced public health infrastructure, one that has the resources to deal with its everyday work and that is well-positioned to quickly pivot and scale up during emergencies.

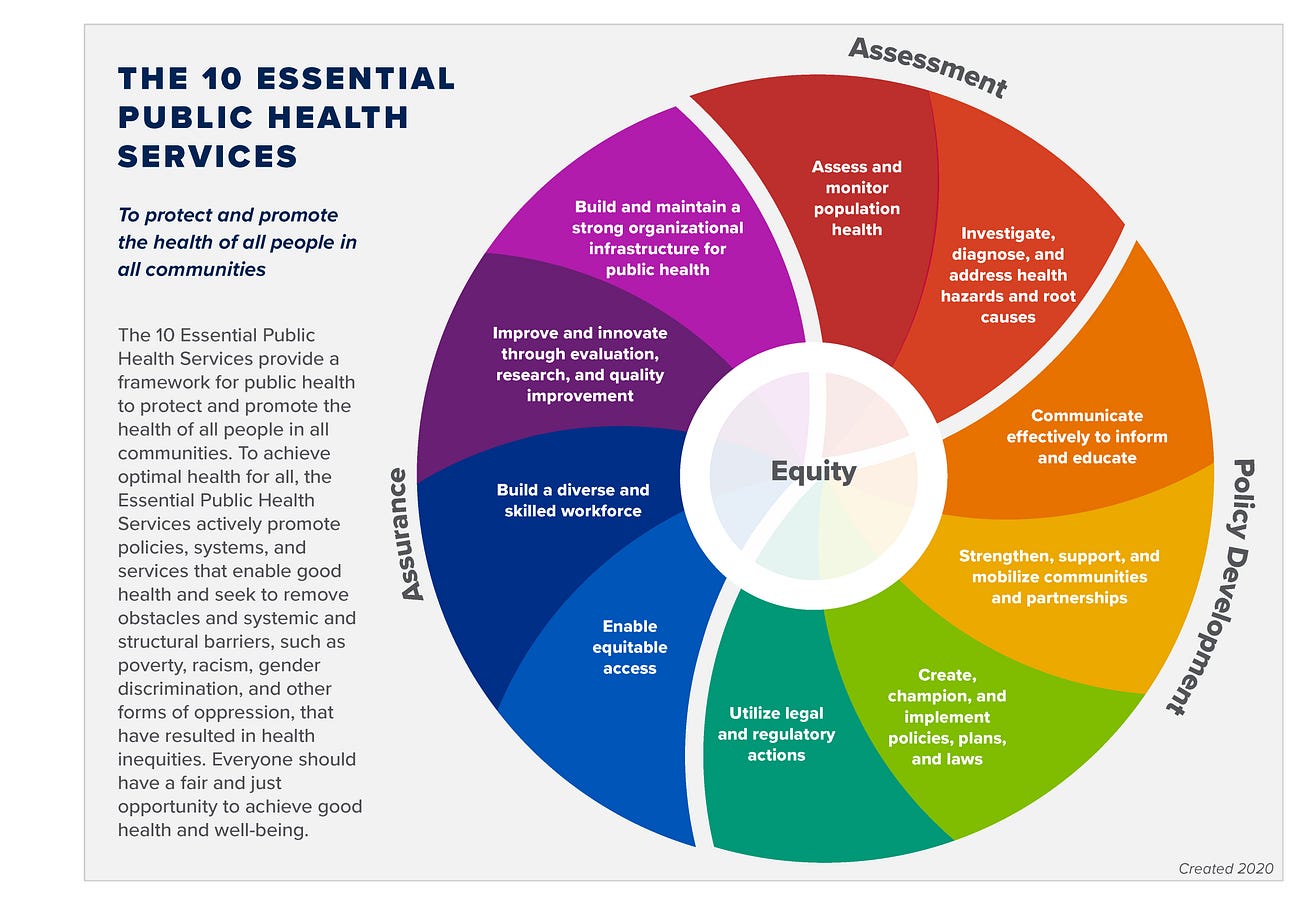

A robust public health system is one that provides the following essential public health services:[20]

· Assess and monitor population health status, factors that influence health, and community needs and assets.

· Investigate, diagnose, and address health problems and hazards affecting the population.

· Communicate effectively to inform and educate people about health, factors that influence it, and how to improve it.

· Strengthen, support, and mobilize communities and partnerships to improve health.

· Create, champion, and implement policies, plans, and laws that impact health.

· Utilize legal and regulatory actions designed to improve and protect the public’s health.

· Assure an effective system that enables equitable access to the individual services and care needed to be healthy.

· Build and support a diverse and skilled public health workforce.

· Improve and innovate public health functions through ongoing evaluation, research, and continuous quality improvement.

· Build and maintain a strong organizational infrastructure for public health.

In addition, to advance equity, successful systems promote structural conditions that support optimal health for all and work to remove systemic barriers that have resulted in health inequities.

And a strong public health system comprises federal, state, tribal, territorial, and local health agencies working with a network that includes healthcare providers, public safety agencies, human service and charity organizations, education and youth development organizations, recreation and arts-related organizations, economic and philanthropic organizations, and environmental agencies and organizations.[21]

BOX: PUBLIC HEALTH DATA MODERNIZATION AND STAFFING NEEDS — WHAT’S THE NEEDED LEVEL OF INVESTMENT?

Experts agree that increased and sustained funding to strengthen the country’s public health system is urgently needed, particularly in the areas of data infrastructure and staffing.

The Data: Elemental to Health campaign, the de Beaumont Foundation and Public Health National Center for Innovations have estimated needed levels of investment in both areas.

Data Modernization

There is strong consensus that the country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic was weakened by fractured and outdated public health data infrastructure.

Ensuring that the COVID19 pandemic experience is not repeated requires sustained investment in data systems that can deliver comprehensive, real-time data during the country’s next public health emergency.

Improved data systems are also a critical element of any efforts to address America’s multiple epidemics of chronic disease and substance misuse and suicide, as well as racial inequities.

The Data: Elemental to Health campaign has called on Congress to invest at least $7.84 billion over five years to modernize the public health data infrastructure, including by investing in five key pillars of data management:

1. Electronic Case Reporting

2. Laboratory Information Management Systems

3. Syndromic Surveillance

4. Electronic Vital Records

5. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System

Additionally, investments need to be made in the local public health workforce and systems compatibility as well as state-level data systems, leadership, management, and integration.[22]

Growing the Public Health Workforce

State, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments are essential to maintaining the security, safety, and prosperity of local communities, yet they are consistently underfunded, making residents more vulnerable to emerging infectious and chronic diseases, and other health threats.

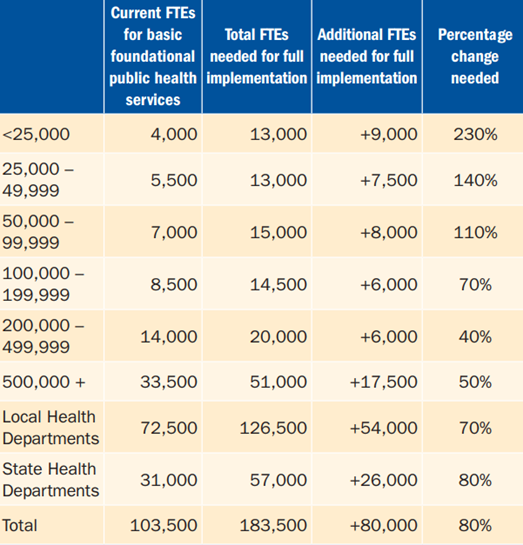

An October 2021 analysis conducted by the de Beaumont Foundation and the Public Health National Center for Innovations found that state and local public health departments need an 80 percent increase in workforce size to ensure comprehensive public health services for all U.S. residents.[23]

The de Beaumont Foundation issue brief, Staffing Up: Workforce Levels Needed to Provide Basic Public Health Services for All Americans, found that state and local public health departments collectively lost 15 percent of their workforce over the past decade and need to hire 80,000 additional full-time employees to establish an adequate foundational workforce and to deliver a minimum set of public health services to the nation. (See Figure 1.)

Specifically, due to existing staffing shortages, local health departments need to add approximately 54,000 full-time employees and state departments need to add 26,000 fulltime employees across differing levels of categories and areas of expertise. (See Figure 1.)[24]

Figure 1: New FTEs Needed by Population Served

NOTE: Estimates are rounded to nearest 500 FTEs and the nearest 10% change.

Source: Staffing Up: Workforce Levels Needed to Provide Basic Public Health Services for All Americans, de Beaumont Foundation[25]

Summary of Policy Recommendations

This report includes recommendations for policy action by the administration, Congress, and state and local officials within four issue areas. A full listing of the report’s recommendation begins on page 32.

1. Substantially Increase Core Funding to Strengthen Public Health Infrastructure and Workforce

Funding for public health must be increased, flexible, and sustained over time.

Critical funding needs include modernized health data and disease tracking systems that are interoperable and that disaggregate data collection and reporting. A second budget priority is a larger, more diverse public health workforce.

2. Invest in the Nation’s Health Security

The nation’s health security can be strengthened by investing in health emergency preparedness (including within the healthcare system), improving immunization infrastructure, growing efforts to address antimicrobial-resistant infections, and addressing the impacts of climate change and other environmental health threats.

3. Address Health Inequities and Root Causes of Disease

The conditions within which individuals are born, grow, live, work, and age are key drivers of their health.

These health drivers, also known as the SDOH, often determine if a community has the resources to support good health for its residents.

During an emergency, they also often mean the difference between resilience and recovery, on one hand, and illness and long-lasting harm, on the other hand. Policymakers should invest in programs that address SDOH, and federal agencies should ensure grants are reaching communities that are most in need.

4. Safeguard and Improve Health Across the Lifespan

Routine public health programs that promote health across the lifespan — ranging from maternal and infant health to disease prevention to support programs for older Americans — were slowed during the pandemic because of the demands on health departments nationwide.

Programs promoting health at all stages of life, including programs that stem chronic disease, prevent adverse childhood experiences, and support behavioral health and suicide prevention, should be a top priority.

The conditions within which individuals are born, grow, live, work, and age are key drivers of their health.

These health drivers, also known as the Social Determinants of Health, often determine if a community has the resources to support good health for its residents.

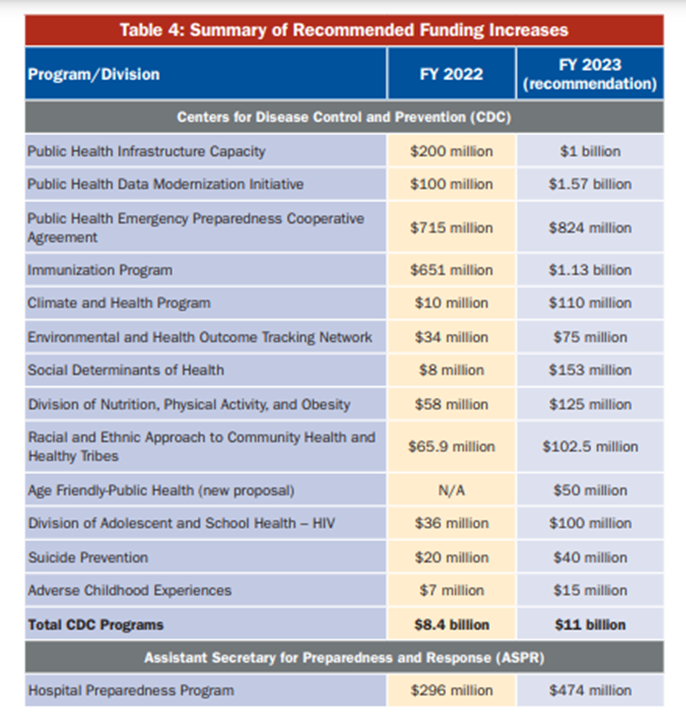

Summary of Recommended Funding Increases for FY 2023

This chart summarizes current funding (FY 2022) and TFAH recommended funding levels (FY 2023) for the CDC and ASPR programs associated with the report’s recommendations.

TFAH recommends that the CDC total funding for programs — encompassing programs discussed in this report and others — be $11 billion in FY 2023. For ASPR’s Hospital Preparedness Program, TFAH recommends increased funding for FY 2023 to $474 million.

References

See the original publication

APPENDIX: Mixed picture for recent funding

The past two years have presented dual realities for health agencies. While there were significant increases in funding during the year, in general those increases were onetime COVID19-specific appropriations and therefore could not be used to correct structural and long-standing funding deficiencies. Within the sphere of standing program budgets, there were both marginal increases and decreases, albeit with larger-than-usual topline increases in fiscal year (FY) 2022. Federal agencies received several infusions of discrete funding to fight the COVID19 pandemic, much of it redistributed to states (and their localities) and territories. However, in general, states and localities could not use this funding to shore up longstanding weaknesses in public health infrastructure, preparedness, and disease-prevention programs, as the funding was directed to immediate pandemic response only. Moreover, these emergency appropriations — while important — are inherently too late to bolster preparedness and prevention efforts. To address threats like COVID-19, the nation needs to sustain higher funding on a year-to-year basis and to invest in planning, workforce, and infrastructure for years before a crisis occurs. Failing to do so is akin to hiring firefighters and purchasing hoses and protective equipment amid a five-alarm fire.

Federal Funding

As the country’s leading public health agency and a primary source of funding for state, local, tribal, and territorial health departments, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is at the forefront of this preparatory work. However, the agency’s historically underfunded budget has not kept pace over the past decade with the nation’s growing public health needs and emerging threats. The CDC’s FY 2022 budget, which does not account for onetime infusions of money from pandemic-relief laws, is $8.4 billion, reflecting a $602 million year-over-year increase.[7]

A serious mismatch remains between documented public health needs and funding levels, as some successful prevention programs lack funding to reach all states. For example, funding to fight obesity has remained virtually flat for years, even as obesity rates continue to increase.

The CDC’s budget rose by 11 percent over the past decade (FY 2013–2022), after adjusting for inflation. However, this increase was not evenly distributed across the agency and its programs. A serious mismatch remains between documented public health needs and funding levels, as some successful prevention programs lack funding to reach all states. For example, funding to fight obesity has remained virtually flat for years, even as obesity rates continue to increase, leaving only enough money to support 16 states as they combat one of the leading drivers of health costs.[8]

The CDC’s annual funding for public health preparedness and response, which includes Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) programs in states, territories, and local areas increased slightly between FY 2021 and FY 2022, from $840 million to $862 million.[9] However, Congress has cut PHEP funding by just over one-fifth since FY 2002, or about half, after adjusting for inflation.

In response to the pandemic, the CDC received several tranches of supplemental money since March 2020. However, these short-term funds were not sufficient to bridge gaps created by the erosion of critical preparedness funds.[10]

· The Hospital Preparedness Program — administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response — is the primary source of federal funding to help healthcare systems prepare for emergencies, such as natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic. Its budget was $515 million in FY 2003 and just $296 million in FY 2022 — a nearly two-thirds cut, after adjusting for inflation.

· The Prevention and Public Health Fund, originally designed to expand and sustain the nation’s investment in public health and prevention, remains at about half the funding level Congress should have provided in FY 2022, due to the redirection of monies to other programs and legislation.[11]

Three other federal agencies with significant public health responsibilities, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Food and Drug Administration all also saw modest operating gains for FY 2022.

State Funding

At the state level, most states (at least 30 states and the District of Columbia) maintained or increased their funding for public health during the 2021 fiscal year, while at least 15 reduced that funding.[12] [13] These data were collected by TFAH for its annual Ready or Not: Protecting the Public’s Health from Diseases, Disasters, and Bioterrorism report. Five states did not report their funding data.[14] State health agencies play a key role in promoting public health and supporting local health departments. They directly engage in population-based primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, developing preparedness plans, coordinating emergency responses, and conducting lab testing, disease surveillance, and data collection.

All states received pandemic response funding, but while those recovery funds were critical to state-level response programs, they were onetime funds that will not provide the sustained support necessary to build the nation’s public health infrastructure.