This is an excerpt of the paperbelow, with the title above, preceded by an Executive Summary by the Editor of the “The Health Revolution — Research Institute”.

Measuring the availability of human resources for health and its relationship to universal health coverage for 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019:

A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019

The Lancet

GBD 2019 Human Resources for Health Collaborators †

May 23, 2022

talentproindia

This is an excerpt of the paper above, preceded by an Executive Summary by the Editor of the “The Health Revolution — Institute”.

Executive Summary

by Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Health Revolution — Institute

Multidisciplinary Institute to achieve the vision of “Better Health for All”

May 25, 2022

What is the context?

The importance of addressing workforce gaps is underscored by studies linking HRH to population-level health outcomes 11, 12 and research suggesting that investing in health workforces promotes economic growth.13

The COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed the importance of health workers for an effective pandemic response.

Additionally, WHO has outlined an ambitious agenda for expanding and improving the quality of health workforces by 2030.16

What is the problem with HRH studies?

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the WHO Health Workforce 2030 strategy have drawn attention to the importance of HRH for achieving policy priorities such as universal health coverage (UHC).

Despite this attention, comprehensive national health workforce estimates based on comparable data and standard methods are not available.

What are the aims of the study?

- to use comparable and standardised data sources to estimate levels of HRH for 16 health worker cadres across 204 countries and territories for a complete time series from 1990 to 2019, and

- to examine the relationship between a subset of HRH cadres and UHC effective coverage performance.

What are the findings?

The authors estimated that, in 2019, the world had

- 104·0 million health workers,

- including 12·8 million physicians,

- 29·8 million nurses and midwives,

- 4·6 million dentistry personnel, and

- 5·2 million pharmaceutical personnel.

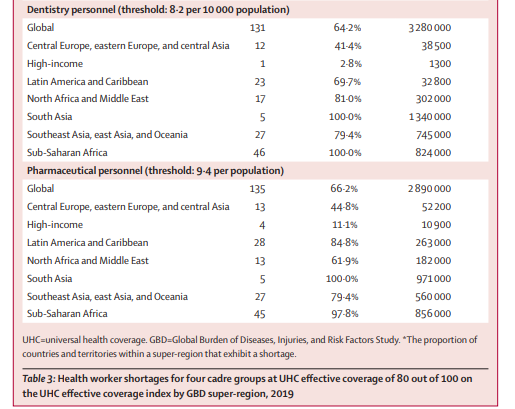

Based on minimum threshold estimates for reaching a UHC effective coverage of 80 out of 100, national health workforce shortages in 2019 amounted to daunting totals [43.2 million in total]

- approximately 6·4 million physicians,

- 30·6 million nurses and midwives,

- 3·3 million dentistry personnel, and

- 2·9 million pharmaceutical personnel.

Interpretation

Considerable expansion of the world’s health workforce is needed to achieve high levels of UHC effective coverage.

The largest shortages are in low-income settings, highlighting the need for increased financing and coordination to train, employ, and retain human resources in the health sector.

Actual HRH shortages might be larger than estimated because minimum thresholds for each cadre of health workers are benchmarked on health systems that most efficiently translate human resources into UHC attainment.

Discussion

Globally, HRH steadily increased between 1990 and 2019; yet, for all cadres, substantial differences persisted both within and across GBD super-regions.

These differences translate into substantial health-worker shortages worldwide compared to estimated workforce levels necessary for achieving high levels of UHC effective coverage.

Shortages in the GBD super-regions of sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia alone accounted for more than half of the global shortfall in each cadre; this finding aligns with shortage estimates published in recent WHO reports on nursing in 2020 and midwifery in 2021.

Minimum density thresholds represent a compromise between the ongoing demand from policy communities for standardised workforce benchmarks and the reality that considerable variation in skill mix undermines the utility of inflexible global targets.

A goal of 80 out of 100 in the UHC effective coverage index reflects a high performance level that still falls within the spectrum of observed attainment among a diverse set of countries examined, making the corresponding thresholds broadly useful for health-system strengthening efforts.

The study observed the greatest shortages in 2019 in densities of physicians, nurses and midwives, dentistry personnel, and pharmaceutical personnel in the super-regions of sub-Saharan Africa, south Asia, and north Africa and the Middle East.

These areas contend with high rates of disease burden as well as expanding health-care needs due to the increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases 40 and due to population growth.

Countries with rapidly growing populations and workforce shortages face a greater challenge.

At the same time, these regions are home to countries and territories with some of the lowest indices of health-care access and quality, reflecting the clear association between adequate HRH densities and health service delivery.

These workforce shortfalls might exist because of gaps in both supply and demand for health workers.

Gaps in supply might be due to insufficient educational capacity.

Limited demand for HRH can occur when there is insufficient employment capacity to absorb available workers.

These dynamics are further exacerbated by a range of issues, including

- the out-migration of health workers, also known as a “brain drain”,45, 46 as well as absenteeism,47

- wars and political unrest,48

- violence against health workers,49, 50, 51 and

- insufficient financial and non-financial incentives to retain health workers.52

What are the recommendations?

Efforts to scale up HRH will need to take into account the complex and varied causes of health worker shortages. WHO’s Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health makes this clear.16

For example, it calls for different policy responses in locations with sizeable health worker out-migrations in contrast to locations with large in-migrations.

And it emphasises that countries will need to address both the supply and the demand factors that produce gaps in HRH.

This is a sizeable task that involves considering the scale and scope of training, education, and the broader workforce, as well as how far or close a country is to the minimum thresholds we estimate.

Progressive realisation of UHC and the health workforce required to achieve UHC is a long-term effort.

High-income locations can adopt responsible recruitment practices detailed in WHO’s global code of practice on the international recruitment of health personnel to avoid further contributing to workforce gaps in GBD super-regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia.53

Responsible international recruitment will need to be coupled with appropriate workforce planning strategies to ensure domestic health-care needs are met.

Middle and low SDI locations seeking to increase HRH might continue to test and pursue retention strategies and incentives to reduce losses from out-migration.54, 55

The time and expenses involved in scaling up the training required for HRH means that expansion of educational opportunities can only be a long-term solution.

Additionally, scaling up educational infrastructure alone will not help if large out-migrations of health-care personnel persist.

In the shorter term, countries can direct funding towards expanding employment capacity.

Underlying most of these policy possibilities is the need to bolster health information systems that can better assess the size and composition of the workforce.

The WHO National Health Workforce Accounts implementation guide 56, 57 recommends multisectoral action to improve standardised data collection on health workforce characteristics.

Our finding that there is substantial variation in UHC effective coverage attainment at given levels of HRH suggests that increasing HRH should be just one element in a broader strategy to increase health coverage.

Achieving UHC will require working conditions where health workers can thrive, boosting engagement, satisfaction, and ultimately workforce productivity.

Other evidence-based strategies might include training physicians to work in rural locations,58 expanding public health programmes, and increasing access to essential medicines.59

A strong health workforce is recognised as being crucial to a range of policy priorities, yet HRH estimates across countries show there are considerable disparities in HRH.

This analysis illuminated widespread shortages in HRH whose elimination will be necessary — albeit insufficient on its own — in global efforts to achieve effective UHC for all people.

As the WHO Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health 16 suggests, successful policy solutions will vary across contexts to address the local drivers of insufficient workforce supply and demand.

Taking these diverse factors seriously is important not only to extending effective health-care coverage in the present, but also to ensuring global health security in the future.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (excerpt)

Measuring the availability of human resources for health and its relationship to universal health coverage for 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019:

A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019

The Lancet

GBD 2019 Human Resources for Health Collaborators †

May 23, 2022

Summary

Background

Human resources for health (HRH) include a range of occupations that aim to promote or improve human health. The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the WHO Health Workforce 2030 strategy have drawn attention to the importance of HRH for achieving policy priorities such as universal health coverage (UHC). Although previous research has found substantial global disparities in HRH, the absence of comparable cross-national estimates of existing workforces has hindered efforts to quantify workforce requirements to meet health system goals. We aimed to use comparable and standardised data sources to estimate HRH densities globally, and to examine the relationship between a subset of HRH cadres and UHC effective coverage performance.

Methods

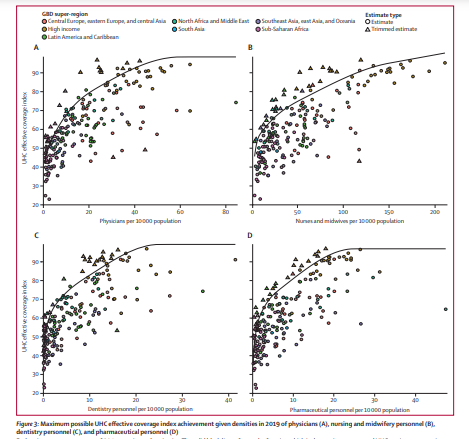

Through the International Labour Organization and Global Health Data Exchange databases, we identified 1404 country-years of data from labour force surveys and 69 country-years of census data, with detailed microdata on health-related employment. From the WHO National Health Workforce Accounts, we identified 2950 country-years of data. We mapped data from all occupational coding systems to the International Standard Classification of Occupations 1988 (ISCO-88), allowing for standardised estimation of densities for 16 categories of health workers across the full time series. Using data from 1990 to 2019 for 196 of 204 countries and territories, covering seven Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) super-regions and 21 regions, we applied spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression (ST-GPR) to model HRH densities from 1990 to 2019 for all countries and territories. We used stochastic frontier meta-regression to model the relationship between the UHC effective coverage index and densities for the four categories of health workers enumerated in SDG indicator 3.c.1 pertaining to HRH: physicians, nurses and midwives, dentistry personnel, and pharmaceutical personnel. We identified minimum workforce density thresholds required to meet a specified target of 80 out of 100 on the UHC effective coverage index, and quantified national shortages with respect to those minimum thresholds.

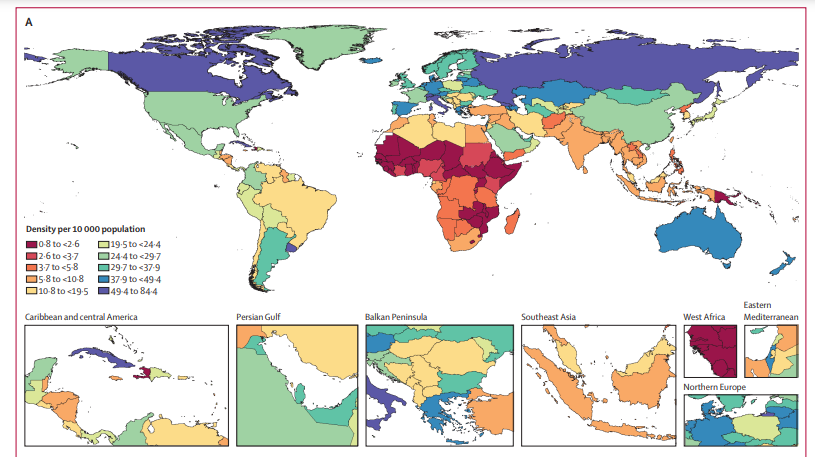

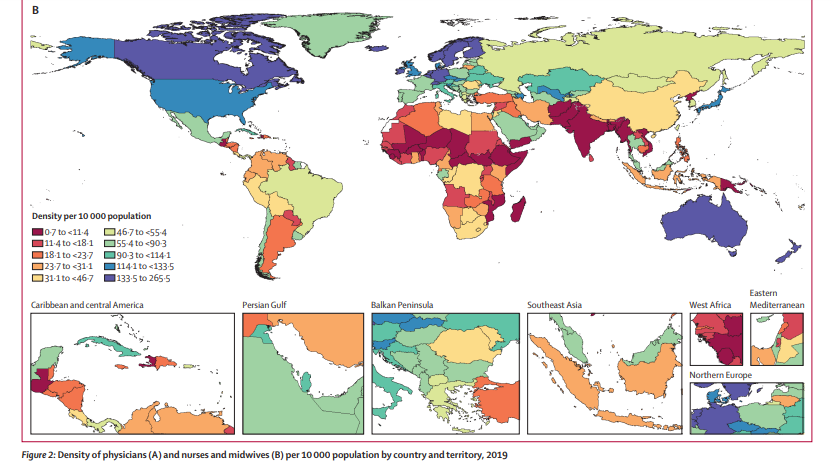

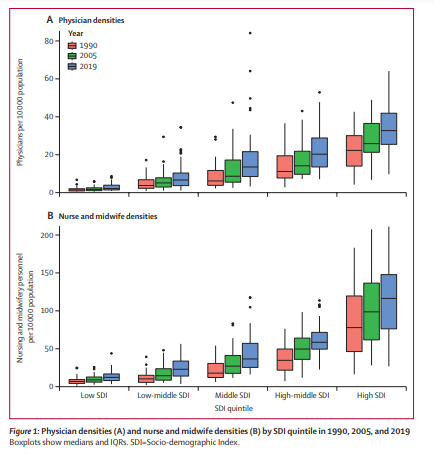

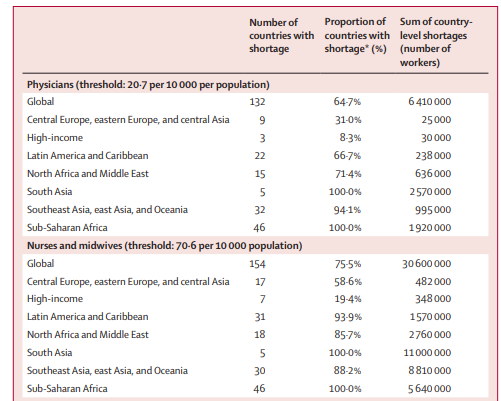

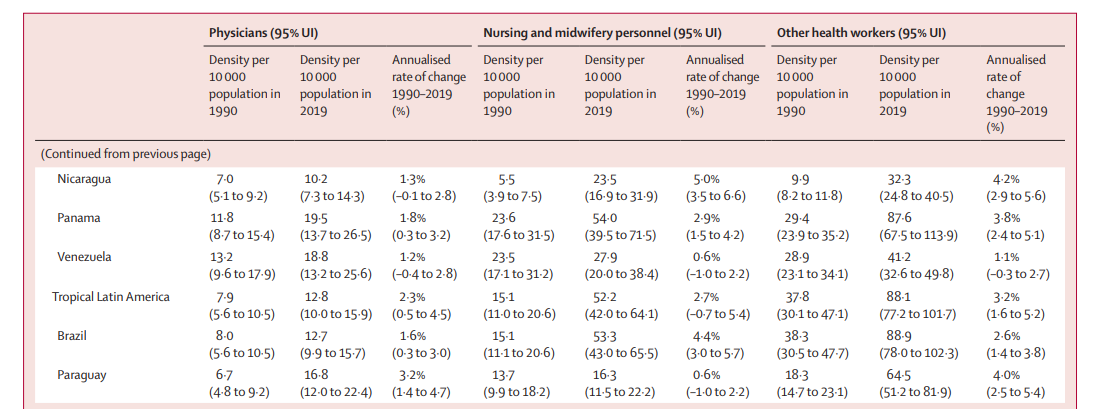

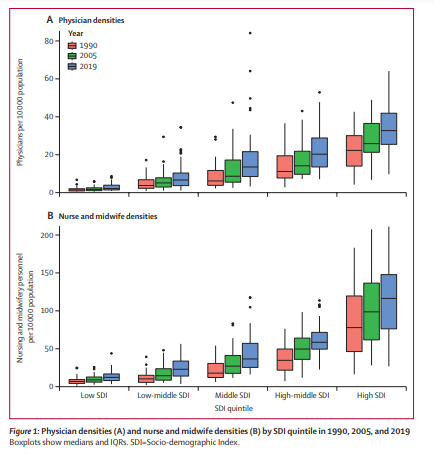

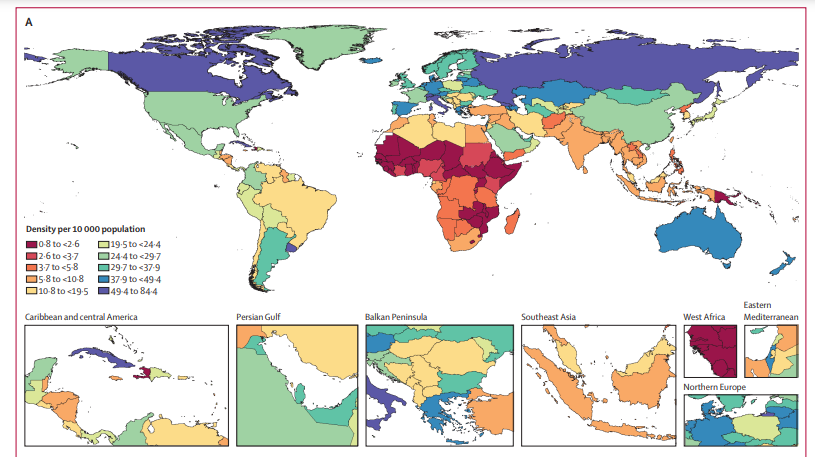

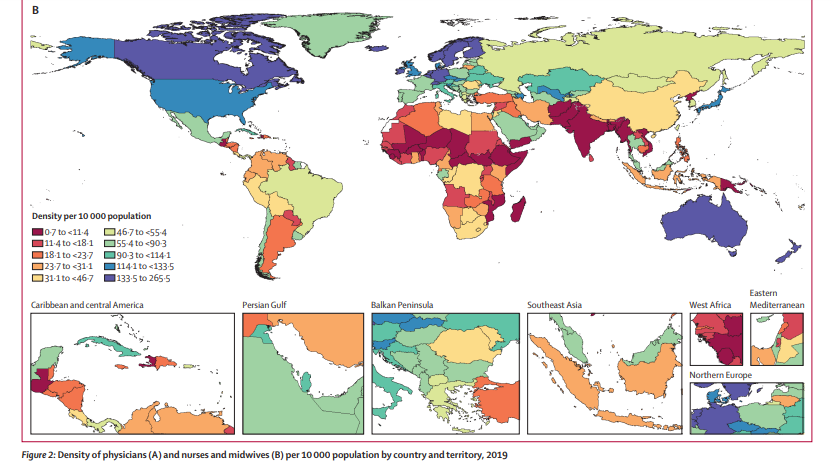

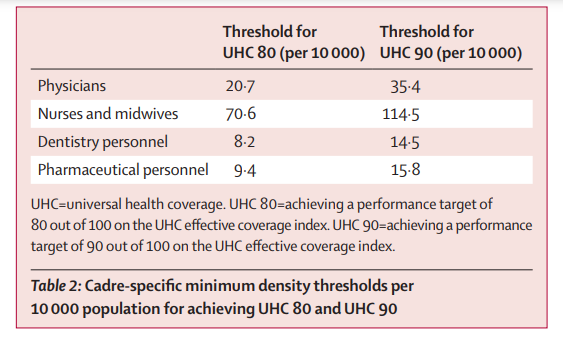

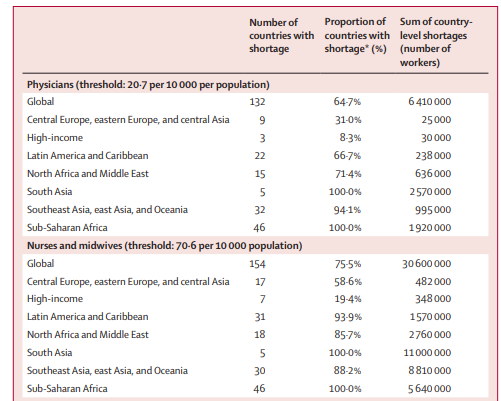

Findings

We estimated that, in 2019, the world had 104·0 million (95% uncertainty interval 83·5–128·0) health workers, including 12·8 million (9·7–16·6) physicians, 29·8 million (23·3–37·7) nurses and midwives, 4·6 million (3·6–6·0) dentistry personnel, and 5·2 million (4·0–6·7) pharmaceutical personnel. We calculated a global physician density of 16·7 (12·6–21·6) per 10 000 population, and a nurse and midwife density of 38·6 (30·1–48·8) per 10 000 population. We found the GBD super-regions of sub-Saharan Africa, south Asia, and north Africa and the Middle East had the lowest HRH densities. To reach 80 out of 100 on the UHC effective coverage index, we estimated that, per 10 000 population, at least 20·7 physicians, 70·6 nurses and midwives, 8·2 dentistry personnel, and 9·4 pharmaceutical personnel would be needed. In total, the 2019 national health workforces fell short of these minimum thresholds by 6·4 million physicians, 30·6 million nurses and midwives, 3·3 million dentistry personnel, and 2·9 million pharmaceutical personnel.

Interpretation

Considerable expansion of the world’s health workforce is needed to achieve high levels of UHC effective coverage. The largest shortages are in low-income settings, highlighting the need for increased financing and coordination to train, employ, and retain human resources in the health sector. Actual HRH shortages might be larger than estimated because minimum thresholds for each cadre of health workers are benchmarked on health systems that most efficiently translate human resources into UHC attainment.

Funding

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Interpretation

Considerable expansion of the world’s health workforce is needed to achieve high levels of UHC effective coverage.

The largest shortages are in low-income settings, highlighting the need for increased financing and coordination to train, employ, and retain human resources in the health sector.

Actual HRH shortages might be larger than estimated because minimum thresholds for each cadre of health workers are benchmarked on health systems that most efficiently translate human resources into UHC attainment.

Considerable expansion of the world’s health workforce is needed to achieve high levels of UHC effective coverage.

Funding

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Selected images

Excerpt of table 1

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (excerpt)

Introduction

Human resources for health (HRH) are crucial to health-system functioning,1, 2, 3, 4 but previous studies have found considerable differences in HRH densities across countries.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

The importance of addressing workforce gaps is underscored by studies linking HRH to population-level health outcomes 11, 12 and research suggesting that investing in health workforces promotes economic growth.13

The COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed the importance of health workers for an effective pandemic response.14

The importance of addressing workforce gaps is underscored by studies linking HRH to population-level health outcomes 11, 12 and research suggesting that investing in health workforces promotes economic growth.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed the importance of health workers for an effective pandemic response.14

Health worker density and distribution is indicator 3.c.1 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), helping to track the “recruitment, development, training, and retention of health workforce[s]”.15

Additionally, WHO has outlined an ambitious agenda for expanding and improving the quality of health workforces by 2030.16

Despite this attention, comprehensive national health workforce estimates based on comparable data and standard methods are not available.

Numerous studies of health workforces have been done at the national, regional, and subnational levels,17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 but these do not present a comprehensive assessment of all or most countries and territories.

WHO’s Global Health Observatory releases workforce density data for various countries and cadres, including physicians, nurses and midwives, dentists, pharmacists, and other groupings.26

Gaps in the data and lack of standardisation across sources, however, restrict the comparability of these numbers.27, 28 T

he Global Health Observatory acts as a repository and WHO density numbers are based on an array of data sources that might differ in their definitions of HRH cadres across contexts.

Additionally, many WHO sources are country reports, which might not capture health workers employed in the private sector and might rely on payroll lists from different providers that count the same health worker more than once.29

Estimates of how many health workers are needed to achieve health-system goals such as universal health coverage (UHC) have been affected by these data limitations as well as by other methodological choices.30

In 2006, WHO based minimum thresholds of skilled health workers (physicians, nurses, and midwives) on the mean workforce levels observed in countries achieving a skilled birth attendance of 80%.6

In 2016, WHO adopted a new method that quantified how many health workers are needed to achieve a median performance on an SDG index composed of 12 tracer indicators.31 WHO’s aggregate density thresholds might not be sufficiently specific in that they do not identify nursing and midwifery needs separately from those of physicians, and they do not identify additional cadres that might contribute to the achievement of health outcomes.

They also imply a 1:1 substitutability between health workers in different cadres that might not always be accurate.

Finally, the WHO thresholds are estimated with respect to crude coverage indicators that might not reflect health service quality, and could pertain to factors beyond the direct activities of health systems (eg, the prevalence of tobacco smoking).32

The present study had two aims:

- to use comparable and standardised data sources to estimate levels of HRH for 16 health worker cadres across 204 countries and territories for a complete time series from 1990 to 2019, and

- to examine the relationship between a subset of HRH cadres and UHC effective coverage performance.

Our study focused on the core cadres highlighted in SDG indicator 3.c.1 metadata: physicians, nurses and midwives, dentistry personnel, and pharmaceutical personnel.

Quantification of the densities and minimum thresholds of HRH required for UHC effective coverage allows us to estimate where there are health workforce shortages that should be addressed.

This manuscript was produced as part of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) Collaborator Network and in accordance with the GBD Protocol.

Discussion

Globally, HRH steadily increased between 1990 and 2019; yet, for all cadres, substantial differences persisted both within and across GBD super-regions.

These differences translate into substantial health-worker shortages worldwide compared to estimated workforce levels necessary for achieving high levels of UHC effective coverage.

Based on minimum threshold estimates for reaching a UHC effective coverage of 80 out of 100, national health workforce shortages in 2019 amounted to daunting totals: approximately 6·4 million physicians, 30·6 million nurses and midwives, 3·3 million dentistry personnel, and 2·9 million pharmaceutical personnel.

Shortages in the GBD super-regions of sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia alone accounted for more than half of the global shortfall in each cadre; this finding aligns with shortage estimates published in recent WHO reports on nursing in 2020 and midwifery in 2021.9, 10

Minimum density thresholds represent a compromise between the ongoing demand from policy communities for standardised workforce benchmarks and the reality that considerable variation in skill mix undermines the utility of inflexible global targets.

Rather than identifying ideal levels of HRH intended to pertain to all contexts, our density thresholds suggest a minimum health workforce common denominator; they represent the minimum human resources needed to achieve UHC performance goals.

A goal of 80 out of 100 in the UHC effective coverage index reflects a high performance level that still falls within the spectrum of observed attainment among a diverse set of countries examined, making the corresponding thresholds broadly useful for health-system strengthening efforts.

Since our study fit workforce thresholds independently to each cadre, the minimum density value for a given HRH category is driven by countries that achieve high UHC with skill mixes that are relatively less reliant on that cadre.

Other locations with skill mixes more reliant on a particular cadre are therefore likely to need workforce densities beyond these minimums.

Consequently, these thresholds and their implied shortages should still apply to locations whose HRH skills mixes heavily favour certain cadres, including other allied health professionals such as community health workers.

Summing the minimum density thresholds calculated for physicians and for nurses and midwives at a UHC effective coverage index of 80 out of 100, the combined threshold is 91·3 per 10 000 population, more than double the WHO threshold of 44·5 for the aggregate of these same cadres.31

Another recent analysis similarly found that WHO methods might underestimate — by nearly double — the true scale of the midwife shortage.44 Unlike WHO’s thresholds, ours are based on a more ambitious health-system performance target, and are primarily driven by locations with maximal, rather than median, translation of HRH to health coverage.

As such, locations with lower productive efficiencies or additional challenges such as sparse population distribution might well need even larger numbers of health workers than those identified in these minimum thresholds.

We observed the greatest shortages in 2019 in densities of physicians, nurses and midwives, dentistry personnel, and pharmaceutical personnel in the super-regions of sub-Saharan Africa, south Asia, and north Africa and the Middle East.

These areas contend with high rates of disease burden as well as expanding health-care needs due to the increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases40 and due to population growth.

Countries with rapidly growing populations and workforce shortages face a greater challenge.

At the same time, these regions are home to countries and territories with some of the lowest indices of health-care access and quality, reflecting the clear association between adequate HRH densities and health service delivery.

These workforce shortfalls might exist because of gaps in both supply and demand for health workers.

Gaps in supply might be due to insufficient educational capacity.

Limited demand for HRH can occur when there is insufficient employment capacity to absorb available workers.

These dynamics are further exacerbated by a range of issues, including

- the out-migration of health workers, also known as a “brain drain”,45, 46 as well as absenteeism,47

- wars and political unrest,48

- violence against health workers,49, 50, 51 and

- insufficient financial and non-financial incentives to retain health workers.52

Efforts to scale up HRH will need to take into account the complex and varied causes of health worker shortages.

WHO’s Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health makes this clear.16

For example, it calls for different policy responses in locations with sizeable health worker out-migrations in contrast to locations with large in-migrations.

And it emphasises that countries will need to address both the supply and the demand factors that produce gaps in HRH.

This is a sizeable task that involves considering the scale and scope of training, education, and the broader workforce, as well as how far or close a country is to the minimum thresholds we estimate.

Progressive realisation of UHC and the health workforce required to achieve UHC is a long-term effort.

By doing a stochastic frontier analysis, we sought to improve UHC — in terms of both access and quality — by improving the allocation of resources.

A realistic understanding of the gaps in UHC provides countries with a clearer picture of what is desirable, even though it might not always be possible to achieve.

High-income locations can adopt responsible recruitment practices detailed in WHO’s global code of practice on the international recruitment of health personnel to avoid further contributing to workforce gaps in GBD super-regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia.53

Responsible international recruitment will need to be coupled with appropriate workforce planning strategies to ensure domestic health-care needs are met.

Middle and low SDI locations seeking to increase HRH might continue to test and pursue retention strategies and incentives to reduce losses from out-migration.54, 55

The time and expenses involved in scaling up the training required for HRH means that expansion of educational opportunities can only be a long-term solution.

Additionally, scaling up educational infrastructure alone will not help if large out-migrations of health-care personnel persist.

In the shorter term, countries can direct funding towards expanding employment capacity.

Underlying most of these policy possibilities is the need to bolster health information systems that can better assess the size and composition of the workforce.

The WHO National Health Workforce Accounts implementation guide 56, 57 recommends multisectoral action to improve standardised data collection on health workforce characteristics.

Our finding that there is substantial variation in UHC effective coverage attainment at given levels of HRH suggests that increasing HRH should be just one element in a broader strategy to increase health coverage.

Achieving UHC will require working conditions where health workers can thrive, boosting engagement, satisfaction, and ultimately workforce productivity.

Other evidence-based strategies might include training physicians to work in rural locations,58 expanding public health programmes, and increasing access to essential medicines.59

Our analysis has a number of strengths.

First, this study estimated health worker densities by use of standardised census and survey data and administrative or registry-based sources adjusted to be consistent with population-based sources. Adjustments were crucial to ensuring estimates were comparable across countries. Administrative and registry data rely on national health information systems that might omit workers in the private sector and double-count public sector workers with multiple positions. Furthermore, such sources do not adhere to a common process for classifying and collecting data on HRH cadres, which compromises comparability across locations. By using all possible data sources, our models included data from 96% of all 204 locations in our study.

Second, our approach to estimating the frontier of UHC effective coverage at a given level of HRH also has important advantages. Traditional stochastic frontier analysis requires specifying the functional form of the relationship between input and output. Our SFM approach avoided this requirement by fitting a production frontier with a flexible semi-parametric model. SFM also incorporated additional information on the uncertainty intervals of the dependent variable directly in the likelihood function to aid in frontier estimation. Additionally, including trimming within the likelihood prevented a small number of outliers from substantially shifting the frontier. This approach could be useful in other health-system performance or efficiency analyses. Future versions of the SFM model could include uncertainty in the fitted frontier and allow for flexible splines on more than one input variable, allowing direct estimation of substitution effects between cadres.

Third, we believe our new health workforce minimum threshold approach will be broadly useful for health-system strengthening efforts. We believe the thresholds for each cadre — physicians, nurses and midwives, pharmacists, and dentists — can be used to promote greater access to or better performance of the health system. We are not suggesting these minimum thresholds are compulsory, but rather aspirational. Each policy maker can take their own experience and use the threshold as a reference. Some locations have better UHC with fewer HRH, and vice versa; some with worse UHC have more HRH. The threshold is a convenient and innovative new metric for trying to determine the gaps. It is a not just a matter of quantity, but also quality.

This study has several limitations.

First, some characteristics of our input data restricted our analysis. Some surveys had relatively small samples sizes for estimating the small prevalence values characteristic of health-worker densities in many places and times. This resulted in large sampling errors. These are not systematic sources of bias, however, because they are just as likely to result in overestimation as underestimation of a given indicator. For most data sources, the level of detail available in standard coding systems was also restricted, precluding disaggregation of some cadres into distinct professions (eg, community health workers and midwives) or by subspecialty (eg, specialist versus generalist physicians). Some of these limitations are inherent to even the most recent versions of such coding systems, whereas others reflect the preponderance of data coded to older versions of a system, such as ISCO-88. Mapping across coding systems and splitting aggregate codes during data preparation resulted in some loss of precision and conditioned the validity of estimates from less granular three-digit input data on the accuracy of available four-digit sources. The self-report nature of sources presents the potential for misclassifying occupations due to response bias or miscoding by interviewers. Our data sources also did not permit us to track whether health workers are employed in full-time or part-time positions, or whether they are professionals or associate professionals. The latter is an important limitation because the skills and competencies of associate professionals tend to be less advanced than those of professionals. Another limitation of the input data is the treatment of nurses and midwives as a single occupational grouping. Nursing and midwifery are separate disciplines that are not interchangeable and ideally require separate analysis. Additionally, available input data rarely provided information beyond the national level, precluding investigation of subnational heterogeneities in the supply and demand for HRH.

Second, this study’s frontier analyses did not account for potential substitution effects between cadres. In practice, roles and responsibilities among various cadres can overlap, particularly for task-shifting subgroups such as nurse practitioners. Consequently, the thresholds identified in this analysis probably underestimate true workforce requirements, because countries driving the frontier for one cadre might be compensating with higher densities in another. For instance, the low physician densities driving a frontier might only be possible with an unusually high density of nurses. In this way, our minimum density thresholds might collectively mask some workforce needs. Densities at or above the minimum threshold for any cadre might also mask deficits of specialists within that cadre grouping. It should also be noted that the UHC index does not include any particular input related to dentistry, although it might broadly represent better performance in dentistry correlated with the inputs. This is important when considering the minimum thresholds for dentistry. More precise estimates of the effective coverage of dentistry needs could improve the precision of minimum thresholds for dentistry.

Third, our analysis does not take into account some crucial characteristics of health workforces. For example, we do not currently produce estimates of the health workforce by age or sex. Analysing human resources for health in the context of gender is vital to discussions of economic development, equity advancement, and gender equity in health systems. We believe this topic both merits and requires a dedicated, separate analysis to appropriately address gender inequities in HRH and UHC. Such an analysis splitting health worker cadres by sex was outside the scope of the existing analysis but is a natural future extension of our research, as detailed below.

Last, we did not consider other important health workforce characteristics. Specifically, we did not examine variations in either the adequacy of workforce training or in workforce performance. Understanding both training and performance globally would require substantial improvements in country-level process-oriented data collection. Nor did we attempt to analyse the proportion of trained workforces that is unemployed, employed in non-health occupations, or that has emigrated from the country. Information on the prevalence of unemployment, non-health employment, and out-migration among workers with health-care training could, however, provide crucial insight into the mechanisms underlying low workforce densities and the relative potential of efforts to expand workforces by increasing supply and training as opposed to demand and retention.60 Our data sources did not allow us to assess either unpaid informal care providers, such as family members, or temporary health workers, such as international humanitarian workers. Regarding the contexts in which health workers practice, our global thresholds are not sensitive to differences in national disease burdens or to varying population densities and distributions, both of which are likely to affect required workforce levels.

This study suggests several avenues for future research.

First, further research should examine key characteristics of health workforces. Research should recognise additional cadres that contribute to UHC attainment across locations and extend the threshold analysis accordingly. Understanding the contributions of specialists, such as obstetricians, paediatricians, and surgeons, is another essential avenue. Work is also needed to quantify when surpluses in some cadres can compensate for deficits in others. Such research could identify the specific contextual factors that make training community health workers and shifting health-care tasks better options for expanding UHC than attempting to increase the density of physicians or of other cadres traditionally emphasised in global policy dialogue.

Second, further study of health workforce composition is warranted. Disaggregating HRH densities by sex and examining differences in the sex distribution among and within cadres is crucial for examining the gendered nature of health work. To provide effective coverage, health systems explicitly rely on women’s paid labour. Notably, nurses and midwives comprise the largest health worker cadre globally, and in some countries more than 90% of nurses and midwives are women.61 In the paid workforce, underemployment, unemployment, and labour wastage continue to be gendered phenomena that disadvantage female health workers.62 Additionally, the provision of effective health care implicitly relies on unpaid labour. Results from the Global Valuing the Invaluable analysis indicate that unpaid labour accounts for 31–49% of women’s total contribution to the health sector, depending on the valuation method,61 and women contribute a disproportionate amount of informal, unpaid labour to the health sector compared to men due to domestic caregiving norms.63 Systematic gender-based discrimination affects female health workers’ paid and unpaid labour, and future research must examine gender differences in the health workforce to empower health workers and promote initiatives that improve gender equity.

Third, the threshold analysis could account for other population health needs and health system goals. For instance, as more countries obtain higher levels of UHC, it will be possible to establish reliable minimum thresholds of HRH with respect to even higher targets of UHC effective coverage. Some work has also assessed HRH densities in relation to disease and injury burden.63 Such research could help societies avert health loss, particularly from non-communicable diseases that are on the rise globally. Information on the availability of gerontologists could help societies prepare to care for ageing populations, for instance, and understanding the prevalence of psychologists, psychiatrists, and other mental health professionals could facilitate efforts to address the global burden of depression and suicide. Research on how the size and composition of the health workforce affect pandemic preparedness is also clearly of paramount importance. The 2014 west Africa Ebola virus outbreak and the more recent spread of this disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo showed how shortfalls in HRH bear not only on UHC but also on global health security more generally.64, 65, 66 The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the crucial importance of addressing these shortfalls for disaster responses and health-system resilience.67

Fourth, additional research above and below the national level would be fruitful. Analyses by region or type of health system could yield more precise HRH targets by taking into account prevalent skill mixes. More granular research is also important because national-level estimates could mask considerable subnational disparities and shortages in health workers and health outcomes. Previous work has highlighted how HRH tend to concentrate in urban areas,68 leaving shortfalls in rural and remote areas that could be rectified through national attention and policies.

Fifth, there is substantial opportunity for investigating how total national health expenditure69 corresponds to the gaps and shortfalls in HRH documented here. In many countries, human resources make up a major part of health sector expenditures, and understanding how these resources are balanced against other demands, such as capital investments in buildings and equipment, as well as drugs and devices, is crucial. Similarly, the allocation of expenditure for HRH is crucial, as investments in different levels of HRH will have different ramifications for both the amount of resources spent as well as the care that can be provided.

Finally, future research could build on existing forecasts of future workforce needs.9, 10, 52 Forecasts could incorporate trends in migration, technology, health financing, and health worker training capacity. This would enable decision makers facing resource scarcities to make timely investments in training and recruitment in anticipation of future scenarios.

A strong health workforce is recognised as being crucial to a range of policy priorities, yet HRH estimates across countries show there are considerable disparities in HRH.

This analysis illuminated widespread shortages in HRH whose elimination will be necessary — albeit insufficient on its own — in global efforts to achieve effective UHC for all people.

As the WHO Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health 16 suggests, successful policy solutions will vary across contexts to address the local drivers of insufficient workforce supply and demand.

Taking these diverse factors seriously is important not only to extending effective health-care coverage in the present, but also to ensuring global health security in the future.

Taking these diverse factors seriously is important not only to extending effective health-care coverage in the present, but also to ensuring global health security in the future.

About the authors

Correspondence to: Dr Rafael Lozano, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA

First names in the list only

GBD 2019 Human Resources for Health Collaborators

Annie Haakenstad, Caleb Mackay Salpeter Irvine, Megan Knight, Corinne Bintz, Aleksandr Y Aravkin, Peng Zheng, Vin Gupta, Michael R M Abrigo, Abdelrahman I Abushouk, Oladimeji M Adebayo, Gina Agarwal, Fares Alahdab, Ziyad Al-Aly, Khurshid Alam, Turki M Alanzi, Jacqueline Elizabeth Alcalde-Rabanal, Vahid Alipour, Nelson Alvis-Guzman, Arianna Maever L Amit, Catalina Liliana Andrei, …

Originally published at

References and additional information

See original publication