COVID-19 has taken advantage of a world in disorder. The IMF predicts that advanced economies will recover more quickly from COVID-19 than emerging market and developing ones.

Chapter 2 of the Report — From Worlds Apart to a World Prepared: GPMB 2021 Annual Report

GPMB

Mr Elhadj As Sy, Co-Chair

October, 2021

This is an excerpt from the report “From Worlds Apart to a World Prepared: GPMB 2021 Annual Report”, focusing on the “Chapter 2 — A Broken World”, edited by the author of the blog.

COVID-19 has exposed a broken world

- one in which access to countermeasures depends on ability to pay rather than need;

- where governments, leaders, and institutions are too often unaccountable to their populations;

- and in which societies are becoming increasingly fragmented, nationalism is growing, and geopolitical tensions are rising.

This broken world failed to prepare for the COVID-19 pandemic and responded inadequately and inequitably once it began.

Unless we can repair these ruptures, the response to the next pandemic is unlikely to be any better.

Inequitable World

The rift between the worlds of “the haves and the have-nots” is growing and is clearly seen in the response to COVID-19.

While countries speak of solidarity and equity, they are collectively unable to deliver on it. The world experienced similar inequities in its response to past health emergencies, such as HIV/AIDS and Ebola.

While some actions were taken, for example, the establishment of The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in relation to the AIDS emergency, and the WHO Health Emergency Programme and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations following Ebola, there was no systemic reform following these crises.

It should therefore come as little surprise that the same inequities persist. If we want meaningful change, we must take a different approach and ‘design for equity’.

The most prominent example of inequality in 2021 has been the imbalance of vaccine and treatment availability.

Access to vaccines and good quality treatment has been determined not by need or equity, but by nationality and position in society.

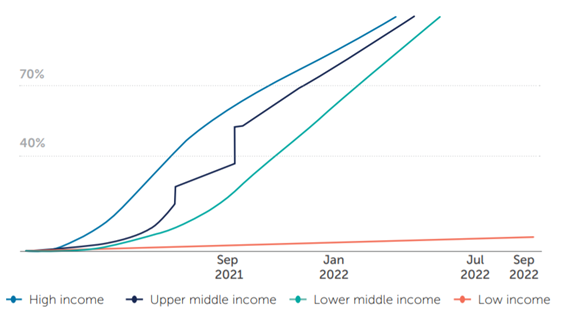

- In fact, rates of vaccine distribution almost perfectly track with country income rankings.[1]

- While vaccines have been available to nearly everyone in high-income countries since mid-2021, LMICs still lack sufficient doses to vaccinate even the most vulnerable, including health care workers — and vaccines may not be available to their whole populations for years.[2]

Unequal purchasing power, trade barriers, and insufficient domestic production capacity have created multiple challenges for LMICs around access to medical supplies, including diagnostics and treatments.[3]

The gap also includes everything from personal protective equipment to oxygen to health workers. Higher-income countries outbid their poorer counterparts for essential medicines resulting in severe shortages in countries that were already under resourced.[4] LMICs have lacked access to quality-assured diagnostic tests while high-income countries (HICs) have enjoyed an array of options.[5]

A key contributing factor has been the geographic concentration of R&D and manufacturing, leaving large areas of the world vulnerable to export bans, transportation bottlenecks, and other distribution obstacles.[6]

Similarly, the clustering of science infrastructure in HICs renders them better equipped to discover, develop, and produce new technologies such as mRNA vaccines.[7]

The problems of inequity are not limited to medical countermeasures.

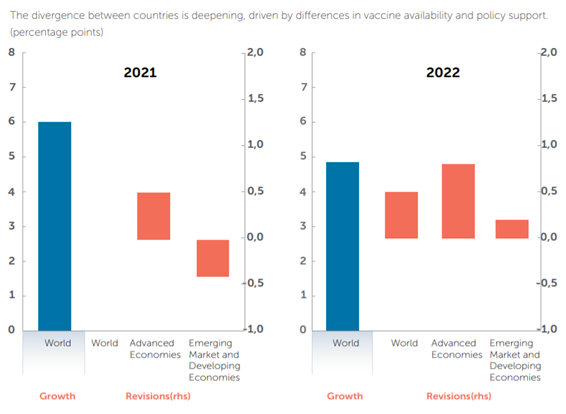

- While the global economy is expected to expand by 5.6% in 2021, it is driven by sharp rebounds in some major economies

- while emerging markets and developing economies continue to flounder.[8]

The World Bank Group has found that this “recovery is underpinned by steady but highly uneven global vaccination and the associated gradual relaxation of pandemic-control measures in many countries, as well as rising confidence.”[9]

Figure 2 | Lopsided recoveries

The IMF predicts that advanced economies will recover more quickly from COVID-19 than emerging market and developing ones. Source: IMF.

Economic inequality has been reflected in country and community capacity to mitigate the impact of COVID-19.[10]

- Job and income losses have impacted lower-skilled and uneducated workers the hardest.[11]

- Women bore the brunt of job losses, seeing a five per cent rise in employment in 2020, compared to 3.9% for men.[12]

- Additionally, 90% of women who lost their jobs in 2020 exited the labour force, which suggests that their working lives are likely to be disrupted over an extended period unless appropriate measures are adopted.[13]

- Young people also have suffered. The effects of missed school — estimated at more than 1.8 trillion hours of in-person learning — are likely to impair some children socially and economically for life.[14]

- Many young adults were unable to successfully transition from school to the workplace in 2020–2021.[15]

Figure 3 | Employment losses in 2020

Decomposition of employment losses in 2020 into changes in unemployment and inactivity, by sex and age group (percentages)

Women and youth have been disproportionately affected by unemployment and inactivity associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Source: ILO

The capacity to provide social protection support has had a big impact on countries’ ability to control the pandemic and mitigate its impacts. Lockdowns, quarantines, and public health and safety measures have been essential to fighting a disease for which we initially had no vaccines or treatments.

Safely implementing and maintaining many of these measures depends on access to basic necessities — including safe drinking water and food, adequate sanitation, reliable energy, access to information or communications technology, and a source of income — a challenge in many parts of the world.[16]

Lower-income countries have had fewer resources to implement public health and safety measures, and mitigate their impact on individuals.

They have therefore had to make harsh tradeoffs between controlling the pandemic and protecting their economies.[17]

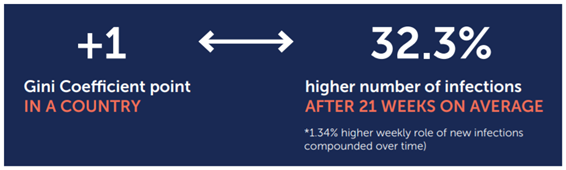

Studies have found a strong correlation between measures of inequality (e.g. the GINI index) and the rate of new COVID-19 cases.[18]

Figure 4 | Correlation between income inequality and rate of weekly new cases

A country’s income inequality is strongly associated with rates of COVID-19 infection. Source: NYU Center on International Cooperation.

Despite the obvious need, multilateral efforts to equalize the response have fallen short. Lacking sustainable, flexible funding sources and grappling with a surge of national self-interest and geopolitical dynamics, multilateral organizations have struggled to ensure equity and solidarity in the global response.[19]

COVAX, the international pooling mechanism designed to support equitable global access to COVID-19 vaccines, has faced a variety of challenges including procurement problems, delays resulting from export bans, market challenges due to the bilateral deals made between many high-income countries and vaccine producers, and the resulting reliance on vaccine donations.[20]

The Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator, ACT-A, was short US $16 billion by mid-October.[21]

WHO set a target of vaccinating at least 10% of the population in each country by the end of September 2021, at least 40% by the end of the year, and 70% of world population by the middle of 2022.

Almost 90% of HICs have now reached the 10% target and two thirds have reached the 40% target. Yet not a single low-income country has reached either target.[22]

Figure 5 | Projected share of population that has received at least one dose

NOTE: Projections based on 7-day rolling average of daily rate of first doses administered. Data as of September 9, 2021 to account for any lag in country reporting.

China reported its first record of number of people who have received at least one dose on June 10, 2021, resulting in a large increase from previous lower-bound calculations. Additionally, China reports data periodically, with report on August visualized once income group has reached 100% coverage. Source: Our World in Data, World Bank, United Nations

Low-income countries are far less likely to meet global vaccination targets than their higher-income peers. Source: KFF, Our World in Data, World Bank and the United Nations

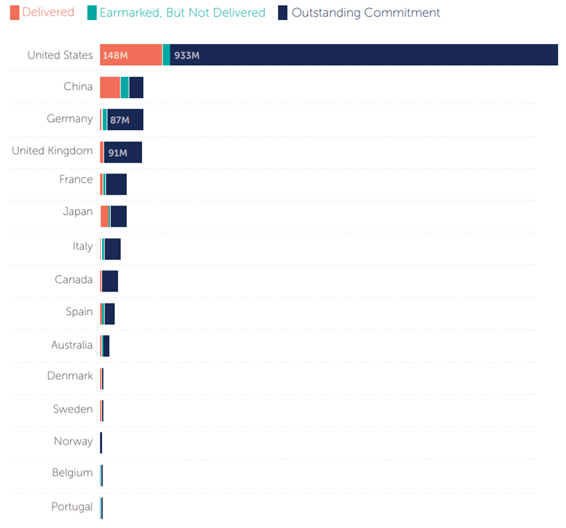

There is some progress — donors have committed a little more than 2 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccine — but this remains significantly below the 11 billion doses needed to vaccinate 70% of the population in all countries.

Further, most of the committed doses have not yet been delivered.[23] Despite the severe shortfall in much of the developing world, some high-income countries are already authorizing third COVID shots as boosters for their general populations.[24]

Figure 6 | Country follow up on vaccine commitments

Several countries, such as Italy, Japan, Spain, and the United States, significantly increased commitments on September 22, 2021.

Chart: CFP/Samantha Kiernan

The large majority of vaccine commitments remain to be fulfilled. Source: CFR: Samantha Kiernan

Many have called for technology transfers that would better distribute manufacturing capabilities and improve global vaccine access.[25]

For example, COVAX partners are working with a consortium of South African vaccine manufacturers, universities, and the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to establish the continent’s first COVID mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub.[26]

But the lack of global equity is also caused by longstanding systemic inequities in the global health emergency ecosystem and the broader international system, and a fundamental misunderstanding of global solidarity as based simply on goodwill and aid, rather than equity and common interest.

Rich countries continue to offer donations of medical countermeasures rather than supporting manufacturing capabilities, technology transfers, and fairer intellectual property (IP) provisions.

For instance, under the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework Standard Material Transfer Agreement 2, vaccine manufacturers can choose to donate doses or transfer technology to LMICs, among other options. Around 420 million doses of pandemic influenza vaccines have been secured, but no company has yet agreed to a technology transfer. ACT-A was built on an often-rigid IP and market-driven model of R&D, with inadequate flexibilities for health emergency preparedness.

International financing of health emergency preparedness and response is based largely on ad hoc, bilateral and multilateral development assistance, rather than a burden-sharing and global common goods approach.

This means that LMICs do not necessarily have a voice and representation in priority-setting and financing is often unpredictable, earmarked, and inflexible, not sustained, and dependent on political cycles, leading to fragmentation, gaps, and incoherence in global preparedness, further amplifying inequities.

In addition, the world lacks effective global and national strategies to involve communities and civil society in decision-making and to better understand and address their needs, marginalizing vulnerable communities.

Unaccountable World

Despite the substantial long-run benefits, leaders have consistently failed to adequately invest in preventing pandemics, instead waiting for a pandemic to arrive before taking action, and thus paying a far higher price.

The GPMB’s 2020 report noted that, even if the world raised its investment in preparedness to adequate levels, it would still take 500 years to spend as much on preparedness as the world is losing due to COVID-19.

Even once a health emergency or pandemic strikes, it often takes countries far too long to respond and when they do it is “too little, too late.”

Leaders make statements and commit to international obligations but do not always follow through.

Although the legally-binding International Health Regulations (IHR), adopted more than 15 years ago, require countries to meet core capacity requirements, in the latest self-assessment only two-thirds of countries reported having full enabling legislation and financing to support needed health emergency prevention, detection, and response capabilities.[27]

A combination of political factors and leadership challenges have been powerful barriers to change.

Polarization, geopolitical conflicts, nationalism, and skepticism of multilateralism have meant that many countries raise the drawbridge rather than seek global solutions.

Due to political cycles, many leaders lack a longer-term vision and fail to give preparedness the continuous resources and attention it requires.

There is frequently a lack of alignment between global and national priorities, as well as across different stakeholders, leading to gaps in investment in important areas of preparedness and an overall incoherent approach to preparedness and response.

The response to health emergencies is not sufficiently multisectoral and is overly focused on medical solutions. There are limited mechanisms to ensure accountability

Despite the universal recognition that pandemics are global problems that require global solutions, the world has failed to take collective action to ensure the delivery of global common goods related to health emergency preparedness.

Nearly 75 years ago, countries established WHO, giving it an extraordinarily ambitious objective of “the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health.”[28]

However, subsequent commitments have not matched the Organization’s lofty founding goal.

Numerous reviews have called for strengthening WHO, and some significant reforms have been made, including the establishment of the WHO Health Emergencies Programme.[29]

However, countries have failed to take the most important step of ensuring WHO has the adequate, predictable, and sustainable financing that would enable it to fulfill its purpose.

As a result, the health emergency ecosystem is complex, inefficient, and lacks agility. It does not deliver a coherent and effective international, regional, and national response to health emergencies.

Divided World

COVID-19 erupted into a polarized world characterized by heightened nationalism, distrust, and inequality.[30] [31] [32] It has only accelerated those trends.[33] [34] [35]

Worse, while the key to containing the pandemic and preparing for the next is collective action, current processes to reform the health emergency ecosystem threaten to exacerbate the existing fragmentation.

The inadequacies start at the top. The UN General Assembly, UN Security Council, World Health Assembly, G7 leaders and G20 leaders, have met over the last year, but with little to show for it other than declarations of intent, and limited evidence that they had a significant impact on the trajectory of the pandemic.

In the most glaring example of dysfunction, division and competition among countries have increased vaccine inequity which contributed to the emergence of new variants, including the devastating surge in the delta variant.

There is no doubt that leaders do want change. Momentum is building around the need for stronger governance, effective systems, and sustainable financing for pandemic preparedness and response through a Financial Intermediary Fund at the World Bank Group.

Proposals are being considered in working groups of WHO Member States, in the G20 under the leadership of the Italian presidency, and by a consortium of nearly 50 countries and several international organizations and institutions, led by the USA and Norway.

However, most of these discussions are taking place in forums that are not always fully inclusive, with limited engagement of some of the countries, communities, and sectors that are expected to contribute to and benefit from these solutions. And as yet, there is limited evidence of the collective will and solidarity that will be essential to deliver effective solutions.

COVID-19 has offered us all a particularly stark view into the severe, widespread health, social, and economic damage pandemics can create.

However, the world’s attention is already beginning to drift to other issues. We have a brief window to make meaningful change, but it is closing fast.

Current efforts are fragmented, involving multiple processes across different forums. There is a grave risk that the geopolitical divides, inequities, and competition that have characterized the COVID-19 response and are playing out again in these discussions, will lead to solutions that perpetuate the existing divisions rather than bridge them.

Reform will require cohesive action. Leaders will have to break through political barriers to build a coherent, inclusive, long-term vision that fully embraces our mutual dependence and shared vulnerabilities in order to achieve a world prepared.

References

See the original publication.

“[The COVID-19 pandemic] has demonstrated the fragility of highly interconnected economies and social systems, and the fragility of trust.

It has exploited and exacerbated the fissures within societies and among nations. It has exploited inequalities, reminding us in no uncertain terms that there is no health security without social security.

COVID-19 has taken advantage of a world in disorder.”

GPMB, A World in Disorder: 2020 Report COVID-19

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

Originaly published at https://www.gpmb.org