the health strategist

institute for strategic health transformation

& digital technology

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Chief Research and Strategy Officer (CRSO),

Chief Editor and Senior Advisor

October 17, 2023

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Highlights

- We develop a framework to reconcile different approaches towards value-based health policies.

- We focus on value created by the health system as a whole.

- Actors within the health system make different contributions to value.

- We discuss a range of policy levers promoting different aspects of value.

Abstract

A variety of methodologies have been developed to help health systems increase the ‘value’ created from their available resources.

- The urgency of creating value is heightened by population ageing, growth in people with complex morbidities, technology advancements, and increased citizen expectations.

This study develops a policy framework that seeks to reconcile the various approaches towards value-based policies in health systems.

- The distinctive contribution is that we focus on the value created by the health system as a whole, including health promotion, thus moving from value-based health care towards a value-based health system perspective.

- We define health system value to be the contribution of the health system to societal wellbeing.

We adopt a framework of five dimensions of value,

- embracing health improvement,

- health care responsiveness,

- financial protection,

- efficiency and

- equity, which we map onto a society’s aggregate wellbeing.

Actors within the health system make different contributions to value, and we argue that their perspectives can be aligned with a unifying concept of health system value.

- We provide examples of policy levers and highlight key actors and how they can promote certain aspects of health system value.

- We discuss advantages of value-based approach based on the notion of wellbeing and some practical obstacles to its implementation.

Infographic

Conclusions [from the excerpt]

This study has provided a new framework that seeks to reconcile the various approaches towards value-based health care.

We do so by defining value to be the contribution of the health system to societal wellbeing.

Our distinctive contribution is that we focus on the value created by the health system as a whole, including health promotion, moving from value-based health care towards a value-based health system perspective.

We have shown that the notion of wellbeing can then be mapped into different domains of value, such as health improvement, health care responsiveness, financial protection, efficiency and equity.

Societal wellbeing can therefore be used to align different perspectives adopted by various actors within the health system, and translate them into concrete goals that can be transmitted coherently to the relevant actors.

The framework can be used to guide future policies at the health system level.

This requires the identification of the key actors for each policy lever and the specification of pathways on how policies can contribute to the common goal of wellbeing through different dimensions of value.

Only by having a clear idea of who is creating what aspect of value will it be feasible to create a health system capable of promoting value effectively by aligning objectives of purchasers, providers, practitioners, citizens and patients.

We have shown that the notion of wellbeing can then be mapped into different domains of value, such as health improvement, health care responsiveness, financial protection, efficiency and equity.

DEEP DIVE

Building on value-based health care: Towards a health system perspective

Elsevier

Peter C. Smith a , Anna Sagan b , Luigi Siciliani c,* , Josep Figueras d

a Imperial College London, Business School, London, United Kingdom

b European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, London, United Kingdom

c Department of Economics and Related Studies, University of York, York, United Kingdom

d European Observatory of Health Systems and Policies, Brussels, Belgium

1. Introduction

Health systems have been seeking to create as much value as possible out of their available resources. The urgency of creating value has been heightened by population ageing, growth in numbers of people with complex morbidities, advances in health technology, increased expectations of citizens, and rapidly increasing health spending [1]. It was amplified by health systems shocks, such as the financial crisis of 2007–2008, and has come under scrutiny in the aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic and its economic repercussions [2].

The development of concepts such as value for money, value-based health care, cost-effectiveness [3], patient-reported outcomes, and patient responsiveness are examples of the preoccupation with creating value in policymaking and academia [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. These concepts reflect similar concerns but they approach the notion of creating value from the viewpoint of various actors in the health system, such as regulators, purchasers, providers, practitioners and citizens.

The goal of this study is to develop a unified policy framework of value-based health care that adopts a health system perspective and focuses on the value created by the health system as a whole. Health systems have multiple, sometimes conflicting, objectives, such as health improvement, financial protection, responsiveness, equity and efficiency. To identify a concept of value that encompasses different health system objectives, we define health system value to be the contribution of the health system to societal wellbeing, representing an aggregate measure of life satisfaction of its citizens.

Health systems have a multiplicity of key actors, and each actor plays a different role and contributes differently. To illustrate how different actors contribute to societal wellbeing, we focus on national policy-makers, purchasers, providers, practitioners, citizens and patients within the health system and describe the contributions they make to this notion of value. However, their perspective will not always be aligned, and we discuss the scope for health system value to align different perspectives. To illustrate how the framework can be used in practice, we provide examples of policy levers that increase value and principal actors at which they are directed.

There is growing literature related to the concept of value-based health care, which often takes the perspective of a specific stakeholder. The most influential approach was developed by Michael Porter and colleagues within the context of the US health system. The framework suggests that competition among providers should shift to value-based competition with providers seeking best outcomes for patients at lowest costs [6]. Providers should focus on complete episodes of care rather than discrete treatments. This shift of focus, known as the value agenda, is expected to improve the fragmented, largely supply-driven system of care. Porter’s value agenda involves: organization of care around medical conditions rather than skills and facilities; systematic measurement of outcomes and costs at patient level; bundled payments for care cycles; integration of care delivery systems; expanding geographic reach of providers; information technology platforms.

This approach takes mostly a provider perspective within a competitive environment, and focuses mainly on health care. It does not address preventive health services at the population level and social solidarity that are central concerns of most health systems. A recent attempt to adopt Porter’s approach in Sweden [7] has shown difficulties in implementing it outside the US.

Another approach was proposed by the European Commission Expert Panel on Effective Ways in Investing in Health (EXPH, [8]).

This proposes four pillars of value created by the health system with a focus on

- equity,

- person-centeredness and social participation,

- in addition to health: achievement of best possible outcomes with available resources (technical value); equitable distribution of resources across patient groups (allocative value); appropriate care to achieve each patient’s personal goals (personal value); contribution of health care to social participation and connectedness (societal value).

Examples of value-based health care initiatives include:

- reallocation of resources through disinvestment for reinvestment;

- addressing unwarranted variation;

- fighting corruption, fraud and misuse of public resources;

- increasing public value in biomedical and health research;

- and regulatory policies to improve access to high-value (but costly) medicines.

However, a gap in knowledge remains in understanding how these different dimensions or interpretations of value should be brought together across domains and stakeholders under one main objective at the health system level. We fill this gap in knowledge by suggesting a unifying framework around the concept of health system value defined as societal wellbeing. We show that this definition of value can guide and align different actors of the health system. Our system view requires a holistic approach that optimizes across technologies, providers, and institutions.

2. Materials and methods

Our main contribution is to extend the notion of value from health care to the health system as a whole, and to examine the implications for health policy design. The current study draws from an earlier and longer policy brief [5]. We develop a conceptual framework which adopts the health system perspective.

In terms of methods, our approach is influenced and guided by the field of public economics [10]. A key notion of public economics is the welfare function, which is defined as a weighted sum of individuals’ wellbeing (‘utility’ in economics jargon). The field of public economics uses microeconomic theory to incorporate efficiency and equity concerns into a welfare function. It explores how different actors in society (e.g. consumers, producers) pursue different objectives and how different incentives generate actions that affect the welfare function. It also explores how the welfare function is affected by policy interventions at the national (centralized) and local (decentralized) level.

In the context of health systems, we map the welfare function into societal wellbeing as an aggregate measure of life satisfaction of its citizens. We apply these notions of public economics in the context of health systems and show how different health system goals (i.e. health improvement, responsiveness, financial protection, efficiency, equity) can be encompassed by our definition of value of health system’s contribution to the societal wellbeing [11], [12]. Second, we use the public economics approach to show how the key health system actors at the micro, meso, and macro levels (e.g. patients, providers, purchasers, policymakers) contribute to achieving improvements in societal wellbeing. Last, we provide examples of common policy levers to illustrate how key actors contribute to different dimensions of value and can be better aligned. The choice of levers is not intended to be comprehensive but to provide illustrations on how value can be enhanced by moving away from the narrow perspectives of specific actors and goals to a holistic one that looks at all actors and goals in the system to ensure that all policy levers contribute to enhancing the overall health system value.

3. Results

3.1. Conceptual framework. Societal wellbeing and health system value

- 3.1.1. Societal wellbeing as the ultimate health system goal

- 3.1.2. Efficiency and health system value

3.1.1. Societal wellbeing as the ultimate health system goal

There is an emerging consensus that narrow metrics of prosperity, such as (Gross Domestic Product) GDP, have limitations in tracking societal wellbeing [13]. GDP fails to acknowledge health systems’ role in promoting better health, and contributing to equity, social protection and cohesion. There is growing interest in more holistic approaches towards measuring progress, mostly centring on the broad concept of wellbeing. It is increasingly recognized that elements such as health, education and training, employment, housing, and less tangible elements (security, gender equality, social belonging and civic connections) contribute to our wellbeing [14] with several attempts to make the concept of wellbeing operationally useful [15,16].

Regardless of its precise formulation, health (and mental health) has been found to make an important contribution to wellbeing, alongside concepts such as educational progress and economic prosperity [17]. Therefore, the health system has a major role to play in promoting wellbeing, as recognized in the 2008 Tallinn charter and reaffirmed on its 10th anniversary [12]. The health system contribution acts both directly in improving health and offering security and social protection, and indirectly through the impact of improved health on factors such as labor productivity, education and savings. It also contributes through creating improved wealth for example by providing employment opportunities [12,18].

We therefore define health system value to be the contribution of the health system to societal wellbeing. The health system is expected to contribute to wellbeing in a number of respects, which are often expressed as a set of objectives for the health system. There is a core cluster of objectives, developed from the World Health Report 2000 [4], that has secured widespread acceptance amongst policy-makers as reflecting their central priorities: health improvement, responsiveness, financial protection, efficiency and equity. It is these strategic goals that should reflect the health system’s concept of value.

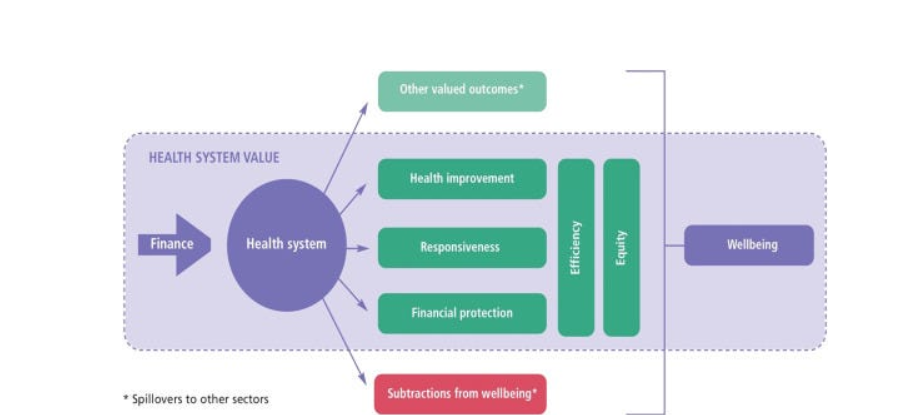

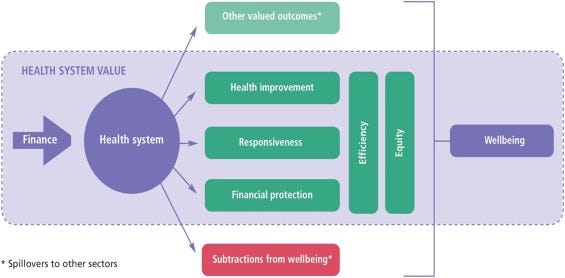

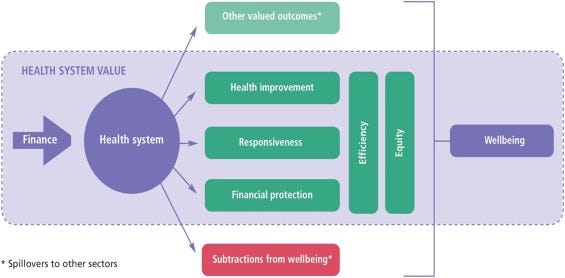

Fig. 1 sets out a framework that captures our concept of health system value. The health system is allocated funds that it is expected to convert into valued health-related outcomes, which in turn improve wellbeing. Health systems aim at providing health services that satisfy patients’ needs promptly (responsiveness) and improve health, and that are free of charge or involve small co-payments (financial protection).

Fig. 1. Value from a health system perspective.

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

In Fig. 1, we include efficiency and equity as transversal objectives (vertical lines) because the delivery and financing of health services necessary to achieve health, responsiveness and financial protection implicitly impact on the health system objective of delivering services equitably and efficiently. By efficiency, we mean that health systems should provide services that generate given health benefits with the lowest level of resources, therefore avoiding unnecessary or harmful treatments. Equity relates to distribution issues across the population in relation to health, access and contributions to financing of health system.

Efficiency is a major concern of health systems. Policy initiatives have been used to enhance efficiency, but inefficiencies remain persistent. Efficiency improvements contribute to wellbeing by reducing waste (which makes little or no contribution to wellbeing) and releasing resources that can then be used for enhanced health services or valued activities in other sectors (see next section).

For each dimension we consider its contribution to wellbeing and the way in which the health system yields that contribution.

Health is central to wellbeing. It is valued as an asset, and as an enabler for individuals to prosper and achieve their potential [12]. Health improvement is the focus of all preventive, disease management and curative health services.

Responsiveness reflects the extent to which health services are aligned with the needs and preferences of the citizens, including patients and their caregivers. A responsive health system improves wellbeing by such alignment. Responsiveness is closely related to patient-centeredness, and secured through the design of health services and actions of practitioners.

Financial protection contributes to wellbeing through the ex-ante reassurance it offers to citizens (before getting ill) that their health care needs will be addressed whatever their financial circumstances, and the knowledge that they will not suffer ruinous financial consequences ex post when seeking access to care (once they fall ill). Contributions of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) towards wellbeing form the basis for this aspect of the health system value.

Efficiency is a major concern of health systems. Policy initiatives have been used to enhance efficiency, but inefficiencies remain persistent. Efficiency improvements contribute to wellbeing by reducing waste (which makes little or no contribution to wellbeing) and releasing resources that can then be used for enhanced health services or valued activities in other sectors (see next section). Many approaches to understanding value do not consider efficiency as an objective, but instead examine other dimensions of value in relation to the inputs consumed.

Equity is an elastic concept that relates to distribution issues across the population. It takes a number of forms, such as reducing avoidable health inequalities, and minimizing inequalities in access to services. Equity is valued because, for altruistic or pragmatic reasons, there is widespread abhorrence of the health inequalities that would arise in the absence of access to health services for the sick and the poor, though its importance is dependent on the moral values of a society.

More broadly, countries differ in the importance they give to each of these dimensions and the contribution each dimension makes to wellbeing. For example, some countries may give more weight to financial protection, while efficiency is prominent in other countries.

Health systems can also produce outcomes that are valued by society but not reflected in core objectives of the health system. In effect, the actions of the health system spill over into domains of other sectors. These spillovers are represented as boxes outside the health system in Fig. 1. For example, a program directed at improving health of schoolchildren may improve school attendance and cognitive development. Such intersectoral spillovers contribute to wellbeing, but are rarely considered within the remit of the health system. Spillovers could also be negative: for example, the deleterious effects arising from excessive prescribing of opioids in some communities.

3.1.2. Efficiency and health system value

Health systems generate value by creating health benefits and non-health benefits (e.g. responsiveness and financial protection). These benefits contribute to wellbeing but should be examined in relation to the costs incurred that ultimately fall on individuals (through taxation, insurance premiums, or out-of-pocket expenses) and detract from wellbeing. For this reason, most concepts of value examine some ratio of valued outcomes to costs, and health system value is closely aligned to the concept of health system efficiency. Many debates related to efficiency translate to debates about value [19].

Economists differentiate between allocative and technical efficiency. Allocative inefficiency arises because the health system has allocated its resources to the wrong mix of services: for example, it may rely excessively on curative services, at the expense of preventive services, leading to unnecessary ill-health and health expenditure, both of which detract from wellbeing and are a form of waste. In contrast, technical inefficiency arises when a provider produces fewer services than it could, given available inputs. Thus, inefficiency can reduce health system value either when the wrong services are produced, or services are produced at greater than necessary cost [19].

Techniques such as cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) [3] have sought to rank services according to benefits (relative to their costs). They are particularly relevant in health systems with a fixed budget to optimize its use. In such health systems, even though a treatment is expected to improve health, its provision may be inefficient if funds could be better spent on more cost-effective treatments (thereby creating more value).

Unnecessarily high production costs can arise from a multitude of sources, including unnecessary diagnostic tests, poor procurement practices, and inefficient care pathways [4,20]. Inefficiencies can arise at any stage of the health production process. It is possible to have highly technically efficient services operating within a health system that is allocatively inefficient, because it provides the wrong mix of services. For example, while primary care and secondary care on their own may be organized efficiently, an incorrect balance between primary and secondary care may lead to allocative inefficiency, if some services provided by secondary care could be provided by primary care at lower costs. Collectively, inefficiencies can be thought of as waste, which is estimated to account for 20–40% of health spending [20].

3.2. How can various actors in the health system contribute to value?

Health systems are complex social constructs with an array of actors whose actions can secure different aspects of value created by the health system. National policymakers make decisions over the financing and organization of health services which affect the degree of financial protection, and the health and responsiveness experienced by patients (i.e. all the objectives outlined in Fig. 1, including equity and efficiency).

Collected funds are then allocated to purchasers, who are responsible for contracting with providers and to ensure allocative efficiency (the right balance of services) to maximize the value created from their available budgets, given their local needs. Contracting will also affect technical efficiency of provision and quality, which in turn affect health and responsiveness and corresponding inequalities in access. It is ultimately the provider organizations and the practitioners who are responsible for the delivery of care with countless personal interactions with patients under the arrangements and regulations set-up by national policymakers and purchasers, which will affect the health system objectives in Fig. 1. Last, citizens and patients contribute to the design of financial and delivery arrangements set by national policymakers through the political process. Citizens contribute financially to the health system, through tax payments or insurance premiums and patients might in addition contribute in the form of user fees. Both have an interest in the overall value created by the health system.

In this section, we describe in greater detail how the various actors contribute to health system value. We argue that some of the confusion associated with the concept of value stems from a failure to recognize and reconcile different perspectives of various actors in the health system.

3.2.1. National policy-makers

The ministry of health and associated agencies are usually the guardians of the health system acting on behalf of the population and legitimized through the political process. Policy-makers in the ministry should be responsible for formulating a concept of value for the health system, transmitting that concept to all actors, and ensuring that value is maximized, both by individual entities and in aggregate. National policymakers within health systems also need to cope with competing interests and demands and resources needed from other sectors. A first policy requirement is to identify a concept of health system value and the intended contribution to wellbeing. High-level goals will usually be formulated in the light of instruments such as national health plans, sustainable development goals and universal health coverage. A problematic aspect of specifying value is the process by which its definition is reached. The ultimate arbiters of the contribution made by the health system to wellbeing should be citizens and patients, but the process of assessing and integrating their views into a statement of value is not straightforward.

Once value has been defined, policy-makers can contribute to value by ensuring that all elements of the health system promote those aspects of value over which they have control. These tasks comprise determining the shape of health system, including financing mechanisms, crystalizing objectives, monitoring performance, and ensuring functioning governance arrangements. They also include the provision of collective services such as disease surveillance and preparedness, and health promotion [21]. Detailed purchasing of health services can be left to purchasers, but national policy-makers should transmit priorities and the concept of value to purchasers.

Finally, national policy-makers are charged with monitoring health effects of policies implemented in other sectors and ensuring that these are not detrimental to health and, ideally, lead to health improvements through cross-sectoral initiatives.

3.2.2. Purchasers

The role of purchasers is to plan and purchase services for a defined population, taking into account national mandates, service and budget constraints and legitimate variations in local health needs and contextual factors. They often take the form of insurers, local health authorities or local governments. The concept of value adopted by purchasers should be shaped by the national concept. However, the extent to which they can pursue value will be constrained by their powers and degree of autonomy [22].

To ensure maximum value, a prime consideration for purchasers is assuring allocative efficiency (the right balance of services) from their available budgets. Contracting also plays a central role, including purchasing and monitoring health services, assuring that they are technically efficient and offer adequate quality. The elements of value on which purchasers are best placed to focus are health improvement, service responsiveness, and aspects of equity and efficiency.

3.2.3. Provider organizations

The health system relies on a range of provider organizations, from small primary care practices to complex tertiary hospitals. The objectives of these entities vary depending on the scope of services, their ownership and market conditions. However, financial sustainability will be central to almost all provider organizations.

Provider organizations can create value to the health system by delivering high-quality and responsive services that generate health and non-health benefits, while keeping costs to a minimum. Whether provider organizations have an incentive to reduce costs is affected by the reimbursement system set up by the purchaser. For example, cost-based reimbursement systems give weaker incentives to reduce costs, while activity-based reimbursement systems with fixed tariffs give stronger incentives to contain costs and increase volume. Purchasers seek to put in place financial and non-financial incentives with those quality and cost objectives in mind.

In pursuit of financial sustainability, providers will be concerned with technical efficiency, which is a key source of value. Larger provider organizations, such as hospitals, seek to improve managerial and clinical processes that reduce unit costs and improve outcomes through internal audits and quality management, adherence to clinical guidelines or patient-reported experience measures (PREMs). This is especially likely if purchasers benchmark provider performance or provide comparative information for patients. However, it is only if gains in technical efficiency translate into lower reimbursement for the purchasers in the short or long term that higher efficiency will translate into higher value at the health system level.

Value and allocative efficiency can be improved by enhancing coordination of care across provider organizations. Failure to integrate various providers for patients with long-term conditions may result in loss of value in the form of reduced health improvement, shortcomings in patient responsiveness, and waste.

3.2.4. Practitioners

A vast range of clinical practitioners contribute to the functioning of the health system. Practitioners can be employed and part of an organization (e.g. a hospital or a primary care practice) or be self-employed; they can be salaried, paid by fee for service or some other financial arrangements. The objectives of individual practitioners are complex, and include career progression, balancing effort, intrinsic motivation and altruistic concerns for patients, and income. Their intended contribution to value is to improve health for service users, and be responsive to their needs, subject to restrictions on efficient treatments and decent but competitive salaries applied by policy-makers, purchasers or provider organizations. The value contributed by practitioners is to some extent aligned with that of provider organizations. The main concern is with the extent to which they secure health improvement and treat service users responsively. Elements of efficiency may also be important when considering the value created by practitioners. For example, unnecessary use of diagnostic services or prescribing branded medicines can be considered health system waste, while adherence to best practice guidelines and reductions of unwarranted variation can promote the value created by practitioners.

3.2.5. Citizens

Citizens should be included in any discussion of health system value. As financial contributors to the health system, through tax payments or insurance premiums, citizens have an interest in the overall value created by the health system. Their views should inform the definition of value created by the health system and ensure it is sufficiently person-centered. Citizens also play a crucial role in maximizing the value created by the health system, either collectively or individually. For example, reducing risky behavior prevents or delays onset of disease and the associated use of health system resources.

3.2.6. Patients

Once falling ill, citizens become patients. While citizens may have a greater focus on efficiency, patients have a focus on health improvement and any user fees they must pay. Patients should also be included in any discussion of health system value to ensure that the care provided is tailored to satisfy their health needs and is patient-centered. Patients can also contribute to value through complementarities of the care provided. For example, once treatment is initiated, its effectiveness may be enhanced if the patient adheres to the recommended regimen. Therefore, behavior contributes to health system value by minimizing the impact of illness and maximizing the effectiveness of treatment. Improved health literacy also contributes to value, resulting in more appropriate use of resources, thereby improving allocative efficiency and reducing waste.

3.3. Examples of policy levers to enhance value

Many policy levers have been motivated by various aspects of health system value. In Section 3.2, we have identified different actors that contribute to value. In this section, we connect policy levers with our framework and different contribution to value presented in Section 3.1. We provide several examples of common policy levers. For each lever, we briefly describe the policy, identify key actors, and explain how they can contribute to value. Table 1 summarizes the policy levers we have chosen to discuss further in this section. The selection of policy levers is not intended to be exhaustive but seeks to cover a range of actors and functions, and dimensions of value. While we are by necessity selective, other levers could be interrogated using the framework.

Table 1. Examples of policy levers to enhance health system value.

PolicyKey actorsContribution to valueWorking across sectors for health: Health in All PoliciesMinistries of health and of other sectorsInter-sectoral co-benefitsFiscal and regulatory measures for health promotion and disease preventionMinistries of health and ministries of financeHealth, equity and efficiencyFunding health care for universal accessNational policymakersAccess to health services, financial protectionSetting a health benefits packageNational policymakers, purchasersPromotion of equity and efficiencyStrategic purchasing for health gainPurchasersImproving efficiency and qualityIntegrated people-centered health servicesProvider organizations, practitionersResponsiveness, coordinated careEvidence-based careNational policymakers, purchasers, provider organizationsReduction in unwarranted variation, equity, quality, healthInvolving patients in their own careNational policymakers, practitionersResponsiveness, efficiency

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

3.3.1. Working across sectors for health: health in all policies

Health in All Policies (HiAP) tackles the determinants of health by seeking to include health considerations in the policies of other sectors [23,24]. Key actors include ministries of health liaising with other sectors, in particular other ministries and government, to raise health awareness, advice on effective and suitable interventions and propose collaborations. Intersectoral governance structures can facilitate this dialogue and collaboration including committees at cabinet, parliamentary and departmental level; joint and delegated budgets; state health conferences, citizens’ hearings and collaborations with industry [25] and civil society [26], [27]. Such actions can create value from a health system perspective because transport, energy, education and other sectors have impacts on health like road injuries and fatalities, air pollution and health risk factors.

3.3.2. Fiscal and regulatory measures for health promotion and disease prevention

Health promotion and disease prevention interventions seek to mitigate risk factors associated with a range of health problems. Key actors include ministries of health and ministries of finance who play pivotal roles in health promotion actions within and outside the health system, with the prime objective of improving health, and to address equity and efficiency. Interventions against health-damaging substances, such as tobacco or alcohol, act on price, availability, and marketing [28]. They can be highly cost-effective or even cost-saving [28].

3.3.3. Funding health care for universal access

Universal health coverage (UHC) seeks to finance certain health services through pre-payment with risk pooling, so that service users do not encounter financial barriers to access or experience financial hardship [29], [30], [31]. Key actors include national policymakers. UHC increases value by improving access to health services and the health of the most vulnerable and poorer groups, therefore addressing equity. It can contribute to health and efficiency by focusing resources where they can secure the largest health gains.

3.3.4. Setting a health benefits package

A health benefits package (HBP) is an explicit statement of the services to which citizens are entitled from publicly-funded health insurance [32,33]. Key actors include strategic purchasers and national policymakers. A HBP increases value by comparing the benefits secured by alternative uses of resources, and seeking to maximize overall health gain. A HBP can also increase value through promotion of equity by ensuring that entitlement is universal or for defined population groups. Health technology assessment offers tools for selecting the HBP therefore promoting efficiency (e.g. Tufts CEA Registry [34], WHO CHOICE initiative [35]).

3.3.5. Strategic purchasing for health gain

The core functions of strategic purchasing relate to deciding what to buy (which services), from whom to buy (which providers) and how to buy (which payment model) [22,[36], [37], [38]]. Key actors are the strategic purchasers. Active strategic purchasing can increase value by purchasing cost-effective services, therefore improving efficiency, and services for groups with high needs, therefore improving equity. Purchasing can also increase allocative efficiency by redirecting provision between levels (e.g. from secondary to primary care).

3.3.6. Integrated people-centered health services

Integrated care refers to a structured effort to provide coordinated, proactive, person-centered, multidisciplinary care by two or more communicating and collaborating care providers [39]. Key actors are purchasers and providers. It requires coordination across providers within and beyond the health sector to address fragmentation of services and improve patient experience [40]. The financial tool used by purchasers to support care integration are bundled payments, i.e. using a single payment to fund a pre-defined set of services by multiple providers for a specific group of patients [40]. Care integration by provider organizations and their practitioners can improve value by improving patient experience through improved coordination and continuity of care [41,42].

3.3.7. Evidence-based care

Evidence-based practice involves the use of the best available evidence (scientific evidence, but also clinical expertise and patient values [43]) in making decisions about the delivery of care. Key actors include national policymakers who can support the creation of relevant evidence, and purchasers who can use such evidence to incentivize organizations with financial and non-financial tools. Evidence-based care can improve value through better quality, safety, and reduced unwarranted practice variations and inequalities in provision of care [44].

3.3.8. Involving patients in their own care

Health care experiences can influence the effectiveness of treatment, adherence and self-care skills [45,46]. Policymakers have implemented strategies to support self-care and self-management, mainly for chronic diseases and within disease management programs [47]. Key actors include national policymakers and practitioners. Involving patients in their own care can increase value principally through improved responsiveness and effectiveness of health services.

4. Discussion

The concept of value-based health care has attracted widespread attention from policymakers. However, the notion of value has differed across actors in the health system. Approaches towards value-based policies have addressed specific aspects of health services in specific health systems. This diversity of perspectives has hitherto limited the power of the notion of value-based health care to transform health systems.

To address this multitude of perspectives, we have proposed in this study to relate value to societal wellbeing. In more detail, we define health system value to be the contribution of the health system to societal wellbeing, representing an aggregate measure of life satisfaction of its citizens. This definition has the advantage of mapping value into only one single concept, that of wellbeing, which in turn can encompass different health system objectives. We have therefore adopted a framework with five broad dimensions of value, embracing health improvement, health care responsiveness, financial protection, efficiency and equity, which can be mapped into society’s aggregate wellbeing. Our framework allows the reconciliation of various approaches by focusing on the value created by the health system as a whole to promote a “value-based health system”.

We show that a common notion of value as societal wellbeing can then be used to align different perspectives adopted by various actors within the health system. Although most actors contribute only partially to the value created by the health system, the common notion of value as societal wellbeing can be used to ensure that all actors work towards a common goal. The formulation of an explicit concept of health system value can be translated into a set of concrete goals and transmitted coherently to the relevant actors. Our proposed approach based on the notion of value as societal wellbeing can also act as a vehicle for improving dialogue and promote joint projects between the health and other sectors [48].

Our framework includes five broad dimensions of value (health improvement, health care responsiveness, financial protection, efficiency and equity). Individual countries could integrate additional dimensions, if they think these are insufficient, as long as their definition arises from processes that reflects the views of citizens and patients.

This study underlines the importance of adopting a value-based approach to all actions of the health system, both preventive and curative. The health system concept of value should lead to an alignment of objectives of purchasers, providers, practitioners and citizens and patients. This is not to say that all objectives or instruments for creating value should be the same. They will be determined by the mission and constraints of the entity under scrutiny. The approach can be implemented in stages as experience unfolds. However, it is difficult to see how the contribution of a health system to national wellbeing can be optimized without adopting a system-wide value-based approach.

Policy levers are usually designed with just one or two dimensions of value in mind, and target a limited range of actors. Our unified framework suggests that policymakers need to assess their impact on all aspects of value (positive or negative) and monitor whether the lever is having beneficial or deleterious consequences for the creation of value.

Good governance is essential to the success of any value-based approach. Many relationships between actors can be conceptualized as a principal–agent relationship. Each agent is expected to deliver some aspect of value to the associated principal, with most actors being both principal in some relationships and agent in others. Individuals and organizations should have a clear allocation of roles and responsibilities. Only by having a clear idea of who is creating what aspect of value will it be feasible to create the integrated health system capable of promoting value effectively. Accountability arrangements should have clarity about what aspects of value it is seeking to address, how that contribution is conceptualized and measured, and what mechanisms are in place to correct shortfalls in the creation of value.

Central to governance are metrics to monitor the creation of value within each principal-agent relationship that supports accountability. This can require the specification of performance measures, aligned with the relevant concept of value, for every actor within the health system. Performance indicators do not need to measure directly the outcomes associated with value, as limitations of performance measurement have been documented. Even effective schemes will be incomplete and imperfect in their ability to capture value. Swedish experiments with value-based health care have found information demands excessive [7]. Policy-makers should therefore ensure that adequate capacity is provided to make governance arrangements effective, but be realistic about the limitations to securing good governance.

More generally, there are significant practical barriers to applying the value-based concept across the entire health system. The complexity of health needs and the associated services seriously affects the ability to develop meaningful metrics for many aspects of value [49]. It may therefore be necessary to adopt a gradual pathway towards a value-based system, focusing first on areas with highest potential. Such priority setting is likely to involve scrutiny of a country’s burden of disease and related instruments for tackling that burden, the feasibility and effectiveness of adopting policy levers, and the availability and effectiveness of governance arrangements.

5. Conclusions

This study has provided a new framework that seeks to reconcile the various approaches towards value-based health care.

We do so by defining value to be the contribution of the health system to societal wellbeing.

Our distinctive contribution is that we focus on the value created by the health system as a whole, including health promotion, moving from value-based health care towards a value-based health system perspective.

We have shown that the notion of wellbeing can then be mapped into different domains of value, such as health improvement, health care responsiveness, financial protection, efficiency and equity.

Societal wellbeing can therefore be used to align different perspectives adopted by various actors within the health system, and translate them into concrete goals that can be transmitted coherently to the relevant actors.

The framework can be used to guide future policies at the health system level.

This requires the identification of the key actors for each policy lever and the specification of pathways on how policies can contribute to the common goal of wellbeing through different dimensions of value.

Only by having a clear idea of who is creating what aspect of value will it be feasible to create a health system capable of promoting value effectively by aligning objectives of purchasers, providers, practitioners, citizens and patients.

We have shown that the notion of wellbeing can then be mapped into different domains of value, such as health improvement, health care responsiveness, financial protection, efficiency and equity.

References

See original article

Originally published at https://www.sciencedirect.com.