International lessons for Health Systems

The Nuffield Trust

Sarah Reed, Laura Schlepper and Nigel Edwards

02/03/2022

This is an excerpt of the report “Health system recovery from Covid-19: International lessons for the NHS”, with the title above, focusing on the Chapter 2 “The recovery challenge across countries”.

The purpose here is to apply this lessons for other countries, and in particular Brazil.

Executive Summary

by Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Chief Editor of “The Health Strategy Blog”

March 10, 2022

What is the context?

- The Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted the provision of routine and elective health services across countries — the full consequences of which are still unfolding.

- All health systems studied took the decision to delay planned health services at different points in the crisis, out of precaution, to reduce transmission and/ or because the virus was straining or overwhelming health system capacity.

- This has contributed to care backlogs that health systems have had to balance alongside ongoing health care demands and Covid-19 resurgences.

Covid-19 has affected health systems to different degrees

Within countries, the health and social consequences of Covid-19 have been uneven.

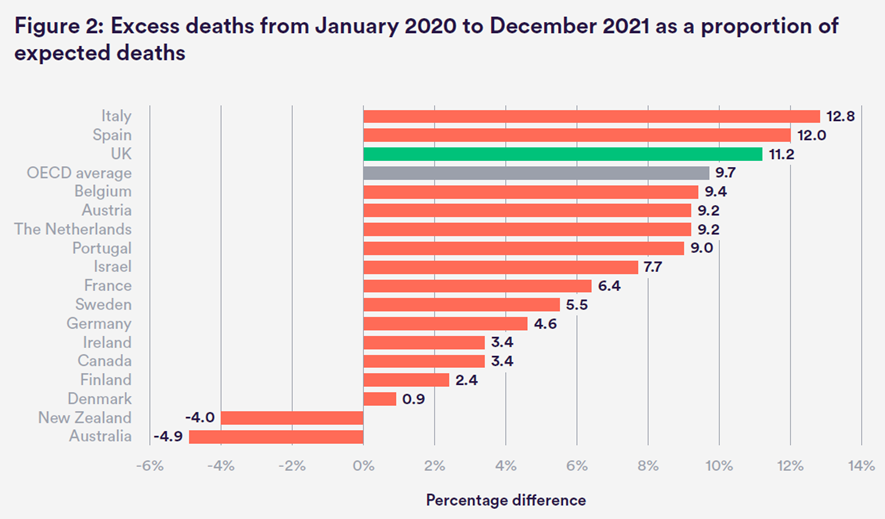

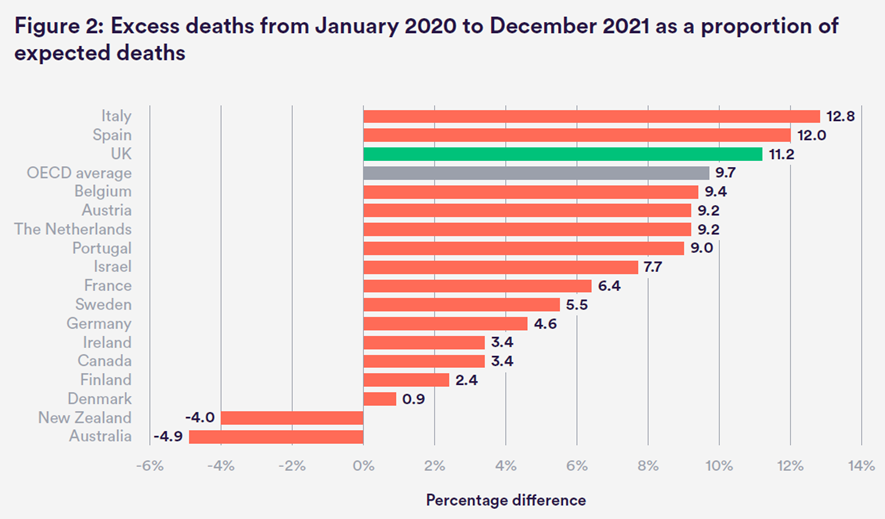

- Figure 2 below illustrates how the countries studied compare in terms of excess mortality, to give a picture of the burden Covid-19 has posed to different health systems.

- On a country level, excess mortality was positive in all countries studied except New Zealand and Australia.

- The UK is among the countries in our sample with the highest level of excess mortality since the pandemic began, experiencing 11.2% more deaths than would otherwise be anticipated in the 24 months between January 2020 and December 2021 (but closer to the OECD average of 9.7% when including all OECD countries).

Countries that have been better able to curb transmission and reduce hospitalisations through effective vaccine deployment will have lessened the burden on their health system, …

Within countries, the health and social consequences of Covid-19 have been uneven.

- Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups and/or socioeconomically disadvantaged communities have experienced higher rates of death and infection from the virus in several OECD countries, including the UK.[2]

- We see this trend in England, as well as other publicly funded health systems such as Australia, Denmark, France, the Netherlands and Sweden.[3]

The scale of the Covid-19 backlog across countries: what we know so far

The extent to which non-Covid-19 health services have been disrupted will also have significant implications for people’s health and wellbeing, and what is required in different countries to rebuild from the pandemic.

- Most health systems report experiencing some form of care backlog, with more patients waiting and waiting longer for care than before the pandemic, although countries vary in terms of the size of their waiting lists and how effectively they have been able to restore activity to pre-pandemic levels of care.[3]

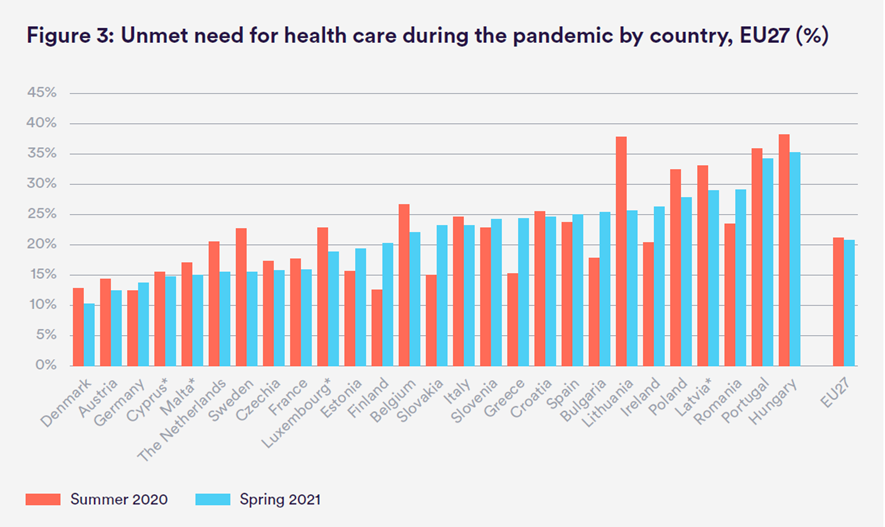

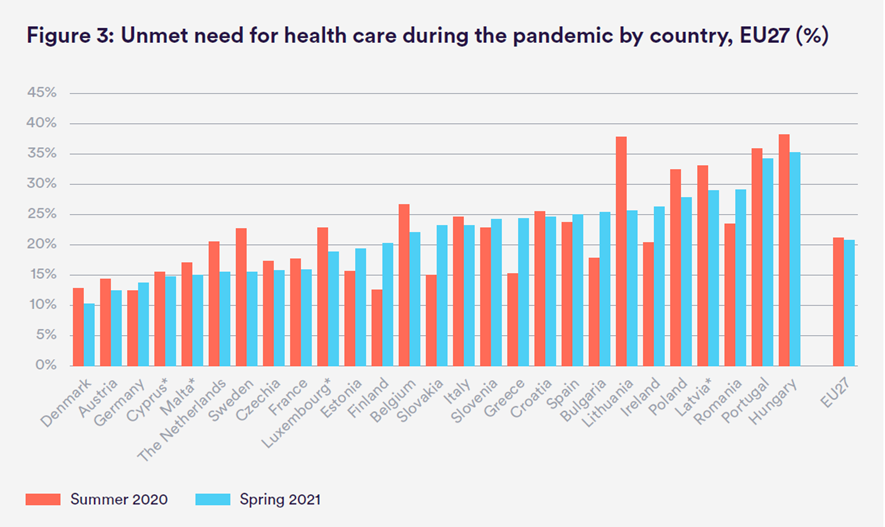

- A large-scale survey of EU countries similarly found wide variation in reported levels of unmet health care need throughout the crisis,

– with more than a fifth (21%) of citizens having missed a medical examination or treatment in the previous year — but

– this ranged from 10% in Denmark to 35% in Hungary (see Figure 3).[4]

Figure 3: Unmet need for health care during the pandemic by country, EU27 (%)

- Across countries, the first months of the pandemic appear to have had the greatest impact in terms of increased waiting times and a reduction in completed treatment pathways.This is true even in countries with relatively low overall case rates as governments took executive decisions to cancel or defer all elective care during the first wave.[9] [10]

- Subsequent surges in Covid-19 hospitalisations also had an impact, but to a lesser degree, as countries adopted more localised approaches and understood more about how to manage the virus.

- Some systems that entered the pandemic with long waiting times have seen those challenges worsen.

– For instance, in Sweden, the proportion of patients waiting longer than 90 days for specialist treatment or surgery grew from 29% in March 2020 to 56% in July 2020.[12]. Volumes of elective activity have since recovered, but the share of patients waiting longer than 90 days remains above pre-pandemic levels, with 40% of patients waiting 90 days or more for specialist treatment in December 2021.[13]

– Likewise, in Ireland, the proportion of patients waiting more than a year for an inpatient or day case procedure grew from 15% in September 2019 to 25% in September 2021.[14]

– In England, the number of patients enduring long waits for care has also deteriorated: in February 2020, there were only 1,613 patients waiting more than a year to start elective treatment,[15] which had ballooned to 306,996 patients by November 2021[16] — nearly a 200-fold increase.

Where waiting times in countries have increased, they have tended to be concentrated among less urgent elective hospital procedures (for example, cataract surgery or hip and knee replacements), while other more time-sensitive operations have been better protected.[1] [2]

However, elective does not mean unimportant or not serious, and these delays can have enormous implications for patients and lead to worsened health outcomes and unnecessary suffering as a result.

And even conditions that many health systems took steps to prioritise, such as cancer, have been affected — with countries reporting lags in referrals, diagnostics and screening volumes, which may result in fewer cases being detected and worsened health outcomes and prognosis for patients over time.

- For example, in France,

– breast cancer screening fell by 14% in 2020 compared to 2019 and

– colorectal cancer screening fell by 11.8% in 2020 compared to 2018 (although screening activity exceeded historical levels in 2021).[19] [20]

– Elective cancer surgery as a whole fell by 6.2% in 2020 compared to 2019.[21]

- In Italy, screening rates for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer dropped by approximately 40% to 45% in 2020 relative to 2019, with estimates that it will take at least four months of standard capacity to clear the cancer screening backlog.[22]

- In Belgium, new cancer diagnoses fell by 44% following the first wave of the pandemic, recovered slowly but declined again following the second wave — although to a lesser extent.[23]

- Cancer services have also been impacted in England:

– between April and June 2020, only 73% of patients started cancer treatment within two months of an urgent referral from a general practitioner (GP), which is 27% lower than in the same period in the previous year.[24]

– By November 2021, performance had declined further, with a third of patients waiting longer than two months to start cancer treatment following an urgent referral.

– Between March and May 2020, the total number of cancers diagnosed fell by 47% but

– has increased thereafter and new cancers diagnosed in December 2020 were only 4% lower than in December 2019.[25]

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (Full version of the chapter)

Health system recovery from Covid-19: International lessons for the NHS

Chapter 2 — The recovery challenge across countries

The Nuffield Trust

Sarah Reed, Laura Schlepper and Nigel Edwards

02/03/2022

INTRODUCTION

As we move into the third year of the Covid-19 pandemic, the challenges confronting the NHS in recovering from its consequences are considerable. Elective services were scaled down during the worst of the crisis to meet the needs of acute and Covid-19-related care. Over 6 million patients are now waiting for treatment — a number that has grown by about 38% since the start of the crisis. More patients may not yet be accounted for as they have been unable to access primary, community or mental health services to have their health concerns addressed.

NHS England and NHS Improvement have set the ambitious goal of delivering around 30% more elective activity by 2024/25than before the pandemic. Yet services must do so with persistent staffing shortages and health professionals still coping with the cumulative stress of the pandemic. Policy-makers and system leaders are tasked with clearing backlogs as quickly as possible, while simultaneously strengthening services so that they are more prepared and resilient for the future.

But the pandemic has left even the most well-equipped health systems vulnerable. Countries around the globe are confronting the challenge of how to recover from the legacies of the pandemic, providing an important opportunity to learn from other countries grappling with common challenges and asking similar questions about what a disaster-proof health system would look like.

This report uses interviews with medical directors, academics and policy-makers across 16 different countries alongside a structured policy analysis of each of those countries to understand how each has approached system recovery. The conclusions provide key learning and emerging lessons for the NHS on recovery and resilience as it delivers its own elective recovery strategy, as well as informing wider international learning.

CHAPTER 2 — THE RECOVERY CHALLENGE ACROSS COUNTRIES

The Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted the provision of routine and elective health services across countries — the full consequences of which are still unfolding.

All health systems studied took the decision to delay planned health services at different points in the crisis, out of precaution, to reduce transmission and/ or because the virus was straining or overwhelming health system capacity.

This has contributed to care backlogs that health systems have had to balance alongside ongoing health care demands and Covid-19 resurgences.

In this chapter we discuss how the pandemic has impacted health systems in different countries, to give a sense of the scale of the challenge and help put the learning on solutions into greater context.

We also discuss common barriers that health systems are facing as part of their recovery from the pandemic, which inform system priorities and strategies.

- Covid-19 has affected health systems to different degrees

- The scale of the Covid-19 backlog across countries: what we know so far

- The known unknowns

Covid-19 has affected health systems to different degrees

How health systems approach recovery will depend in part on the severity and scale of the Covid-19 outbreak in different countries, and the capacity of health systems to deal with the challenges that the pandemic has posed.

Figure 2 below illustrates how the countries studied compare in terms of excess mortality, to give a picture of the burden Covid-19 has posed to different health systems.

Source: Our World in Data based on the Human Mortality Database and World Mortality Dataset. Data were downloaded from OWID on 10 February 2022.

Excess mortality is an important indicator because it measures the total number of deaths over and above what would normally be expected over a certain timeframe.

This gets around differences in how countries might record, register and code Covid-19 deaths, which could underestimate the true figures.[1]

It also gives an indication of deaths from other causes that could be attributed to the crisis but are not caused by Covid-19 directly (that is, health systems being overwhelmed and resources being diverted away from non-Covid-19 conditions).

On a country level, excess mortality was positive in all countries studied except New Zealand and Australia.

The UK is among the countries in our sample with the highest level of excess mortality since the pandemic began, experiencing 11.2% more deaths than would otherwise be anticipated in the 24 months between January 2020 and December 2021 (but closer to the OECD average of 9.7% when including all OECD countries).

The level of excess mortality and the extent to which health systems have been affected by the pandemic will be influenced by factors outside of health systems’ direct control, including the timing and effectiveness of public health measures, wider policy actions and population behaviour.

Countries that have been better able to curb transmission and reduce hospitalisations through effective vaccine deployment will have lessened the burden on their health system, …

… which makes an ongoing containment and vaccine strategy an important variable in recovery and the relative size of care backlogs that countries will ultimately face.

That the UK had higher excess mortality than other countries studied suggests that the NHS has had more strain placed on its health system, from which it must now recover.

It is also important to recognise that, within countries, the health and social consequences of Covid-19 have been uneven.

Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups and/or socioeconomically disadvantaged communities have experienced higher rates of death and infection from the virus in several OECD countries, including the UK.[2]

The reasons for this are structural and interact in complex ways, but working in low-paid or unstable employment, living in crowded accommodation or having underlying health issues increases risk of transmission and mortality.

These inequalities may grow further given that the care disruptions that the crisis has caused may also be felt differently across populations. Many countries entered the pandemic with pre-existing socioeconomic inequities in access to health care and health status, which meant lower-income and/or minority ethnic populations experienced longer waits for care.

We see this trend in England, as well as other publicly funded health systems such as Australia, Denmark, France, the Netherlands and Sweden.[3]

This too will contribute to the different challenges health systems face in recovery, and will be a key consideration for countries as they seek to reduce care backlogs or risk entrenching inequities further.

The scale of the Covid-19 backlog across countries: what we know so far

The effect of the pandemic of course cannot be understood by mortality alone; the extent to which non-Covid-19 health services have been disrupted will also have significant implications for people’s health and wellbeing, and what is required in different countries to rebuild from the pandemic.

The many methodological differences in how and what health systems measure to record waiting times make it difficult to meaningfully compare care backlogs across countries.

Health systems differ in terms of whether they measure the ‘ongoing’ or ‘completed’ waiting period, what kind of care the patient is waiting for, and where, in an episode of care, measurement starts and stops.[1]

Also, waiting lists and activity levels are not always recorded at the national level (for example, in Austria, Belgium, France and Germany) or reported on routine timescales, further obscuring how much we can understand about the pace of recovery in different systems.

Health systems also entered the pandemic with different targets or waiting-time standards for health care services, which can also reflect contextual differences in resources and constraints across countries (see Appendix A).[2]

However, some indicative data are available at the national level to help build a picture of the recovery challenge in different countries (see Appendix B for an overview), even if not fully comparable.

Most health systems report experiencing some form of care backlog, with more patients waiting and waiting longer for care than before the pandemic, although countries vary in terms of the size of their waiting lists and how effectively they have been able to restore activity to pre-pandemic levels of care.[3]

A large-scale survey of EU countries similarly found wide variation in reported levels of unmet health care need throughout the crisis,

· with more than a fifth (21%) of citizens having missed a medical examination or treatment in the previous year — but

· this ranged from 10% in Denmark to 35% in Hungary (see Figure 3).[4]

Figure 3: Unmet need for health care during the pandemic by country, EU27 (%)

Source: Eurofound (2020) ‘Living, working and Covid-19 data’. www.eurofound.europa.eu/ data/covid-19

Unsurprisingly, it appears that countries with a relatively lower prevalence of Covid-19 have been better able to maintain access to elective care during the pandemic, although disruptions to services still occurred.

We see this in Australia where public hospitals report being able to catch up on backlogs between waves of the virus, and median waiting times for elective surgery remaining fairly constant in 2020 compared to the previous year.[5]

In Finland, the number of patients waiting more than six months to receive elective hospital care grew from 2% to 12.9% following the first wave in 2020, but improved to 4.6% by April 2021.[6]

And in Denmark, average waiting times for most services recovered to pre-pandemic levels by autumn 2020, although still lagged in some surgical areas.[7] In March 2021, the Danish government reinstated the care guarantee that all patients would access diagnosis and treatment within one month of referral, which had been temporarily suspended during the pandemic.[8] However, the latest Omicron wave resulted in a higher incidence of Covid-19 in several countries studied that had previously maintained lower rates of transmission, so may impact activity levels and cause waiting times to build up further.

Our waves haven’t been as severe, so we’ve been able to maintain normal activity for the most part. Intensive care and patients in hospital haven’t been in crisis. Elective activity has mostly been possible. Part of the lags in activity are due to fewer patients coming forward.

(Ministry of Health, Finland)

Across countries, the first months of the pandemic appear to have had the greatest impact in terms of increased waiting times and a reduction in completed treatment pathways.This is true even in countries with relatively low overall case rates as governments took executive decisions to cancel or defer all elective care during the first wave.[9] [10]

Subsequent surges in Covid-19 hospitalisations also had an impact, but to a lesser degree, as countries adopted more localised approaches and understood more about how to manage the virus.

This is the same pattern observed in the UK, with treatment activity dropping dramatically between March and May 2020, before falling again between November 2020 and January 2021 — although far less than during the initial drop.[11]

One paradoxical situation for our state health system was the fact that we had managed to keep Covid-19 to extremely low levels but had to manage, like in many countries, [a] backlog in elective activity. Being Covid-19-free for many months during the pandemic enabled us to get the system back to normal activity and significantly reduce this backlog.

(Agency for Clinical Innovation, Australia)

Some systems that entered the pandemic with long waiting times have seen those challenges worsen.

For instance, in Sweden, the proportion of patients waiting longer than 90 days for specialist treatment or surgery grew from 29% in March 2020 to 56% in July 2020.[12]

Volumes of elective activity have since recovered, but the share of patients waiting longer than 90 days remains above pre-pandemic levels, with 40% of patients waiting 90 days or more for specialist treatment in December 2021.[13]

Likewise, in Ireland, the proportion of patients waiting more than a year for an inpatient or day case procedure grew from 15% in September 2019 to 25% in September 2021.[14]

In England, the number of patients enduring long waits for care has also deteriorated: in February 2020, there were only 1,613 patients waiting more than a year to start elective treatment,[15] which had ballooned to 306,996 patients by November 2021[16] — nearly a 200-fold increase.

We didn’t start the pandemic in a good place in terms of access. A lot of existing challenges with long waits that have been [the] focus of government policy over [the] past 10 years are now being accelerated.

(Tallaght University Hospital, Ireland)

Where waiting times in countries have increased, they have tended to be concentrated among less urgent elective hospital procedures (for example, cataract surgery or hip and knee replacements), while other more time-sensitive operations have been better protected.[17] [18]

However, elective does not mean unimportant or not serious, and these delays can have enormous implications for patients and lead to worsened health outcomes and unnecessary suffering as a result.

And even conditions that many health systems took steps to prioritise, such as cancer, have been affected — with countries reporting lags in referrals, diagnostics and screening volumes, which may result in fewer cases being detected and worsened health outcomes and prognosis for patients over time.

For example, in France,

- breast cancer screening fell by 14% in 2020 compared to 2019 and

- colorectal cancer screening fell by 11.8% in 2020 compared to 2018 (although screening activity exceeded historical levels in 2021).[19] [20]

- Elective cancer surgery as a whole fell by 6.2% in 2020 compared to 2019.[21]

In Italy, screening rates for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer dropped by approximately 40% to 45% in 2020 relative to 2019, with estimates that it will take at least four months of standard capacity to clear the cancer screening backlog.[22]

In Belgium, new cancer diagnoses fell by 44% following the first wave of the pandemic, recovered slowly but declined again following the second wave — although to a lesser extent.[23]

Cancer services have also been impacted in England:

- between April and June 2020, only 73% of patients started cancer treatment within two months of an urgent referral from a general practitioner (GP), which is 27% lower than in the same period in the previous year.[24]

- By November 2021, performance had declined further, with a third of patients waiting longer than two months to start cancer treatment following an urgent referral.

- Between March and May 2020, the total number of cancers diagnosed fell by 47% but

- has increased thereafter and new cancers diagnosed in December 2020 were only 4% lower than in December 2019.[25]

The known unknowns

This speaks to a larger problem, where several health systems are still reporting ‘missing’ patients as fewer patients join waiting lists than would normally be expected.

While some patients may not be coming forward as they are able to manage their care effectively on their own, it could mask unmet need and store up challenges for the future if patients present later and in a more serious condition.

In some countries, such as Italy, Portugal and Spain, waiting lists appear to be stabilising or even decreasing in certain areas, as treatment activity reaches or exceeds historical levels.

Data suggest that, in part, this may be due to fewer referrals being received from primary care as patients avoid accessing services out of concerns about the virus, or patients have difficulty accessing appointments.

Similarly, in the Netherlands, waiting lists have reached pre-pandemic levels in several key areas, but experts have warned this might bring false hope as there were 1.48 million fewer referrals between March 2020 and August 2021.[26]

These concerns are shared in the NHS, where between 7.6 million and 9.1 million referrals for elective care could be missing in England from March and September 2021, according to estimates from the National Audit Office.[27]

Our waiting lists have reduced, but this is because there have been fewer new referrals for things like cataract, hip and knee and other elective surgeries… people are now arriving in a worse situation because of delays.

(Catalonia Health Board, Spain)

A challenge has been capacity in primary care — which is still unable to be as responsive to [the] non-Covid needs of patients because so many responsibilities have shifted onto them during the pandemic. They were tasked with calling and updating [the] status of patients at home being remotely monitored with Covid-19, and now are managing vaccine rollouts — so access is a problem. And it creates a problem in hospitals, because patients are coming with later diagnoses, where screening hasn’t been done, and presenting with more advanced pathologies.

(Portuguese Association of Hospital Managers)

There is also a high degree of unpredictability in terms of how patient needs will evolve and what future capacity requirements will be required to address them.

The full range of the long-term health effects of the pandemic is still unknown, with many countries reporting increased numbers of patients with mental illness and/or ‘long Covid’ symptoms that need to be managed within existing constraints.6

Experts from New Zealand cautioned that the health consequences of disasters can take years to understand, remarking how cardiac events and the risk of cardiovascular disease in Canterbury on the South Island increased significantly in the year following the major 2010 earthquake there, but only became visible many years later.[28]

Health systems must therefore grapple with unknowns

- about not only how many patients will return to waiting lists,

- but also at what timescale,

- and with what degree of complexity.

This makes ascertaining the true size and nature of backlogs and the scale of recovery needed a significant challenge.

We can see that while the Covid-19 pandemic has affected countries to different degrees and countries are entering recovery from different starting points, health systems must confront common challenges with how to address rising waiting lists.

The next chapter draws out lessons and reflections from international experience that may help the NHS as it develops and implements its own plans for recovery, to not only restore access to care as quickly as possible, but also to plan differently for the future to be better prepared for the next crisis.

References

See the original publication.

Originally published at https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk on March 2, 2022.